“She’s famous for her use of negative space.” The security guard’s soft voice wafted over to me from the corner of the gallery. I stood in the white cathedral of LACMA’s Broad Contemporary building, narrowing my eyes at a huge expanse of what looked like nearly nothing.

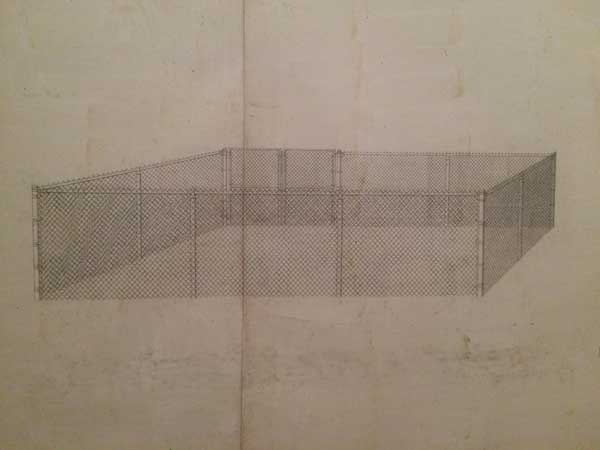

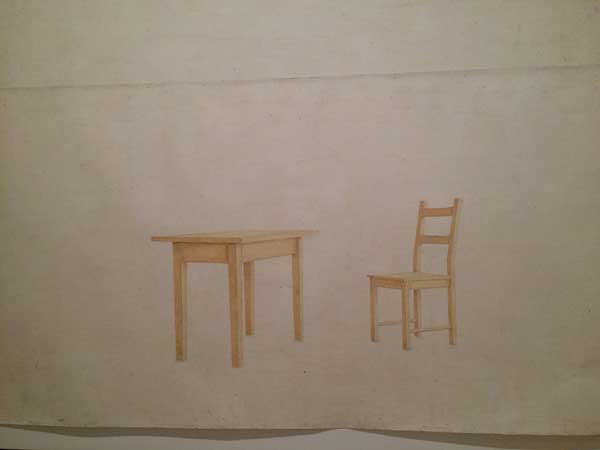

MacArthur “Genius” Grant-winning Toba Khedoori’s massive and recondite oil-on-wax drawings of a table and a chair, a segment of a brick wall, an empty stadium, and a chain-link fence hovered in the room like the fading afterimages of a distressing dream. The unoccupied chair and table, expertly rendered and daubed with faint beige paint, drifted within a vastness of pale and unmarked wax paper (Untitled) (table and chair) 1999. The evacuated stadium (Untitled), 1996 and fence (Untitled) 1996, too, appeared to hang within two vellum-colored vacuums. The exquisitely conjured brick wall levitated in another sea of blankness, accessorized with faint pencil marks made with a ruler (Untitled) (wall) 1995. All issued from the late 1990s, early 2000s, looking like architectural or design drawings made for so many discarded projects.

“What?” I asked, turning around. I had just snapped an extreme close-up of the brick wall, so that the picture filled with rectangles instead of confusing zilch. I am in my 40s, Latina, and skeptical. The security guard was in her 20s, female, black, and looked around the room with a bright face. She wore LACMA’s anonymous gray uniform and a white shirt, and solid, comfortable black shoes. Visitors scattered across the floor, gazing at the drawings with unsure expressions, but the guard studied the images with confidence.

“The artist,” the guard said, “She made negative space her own thing. She thought about it, and made it her signature. She’s famous.”

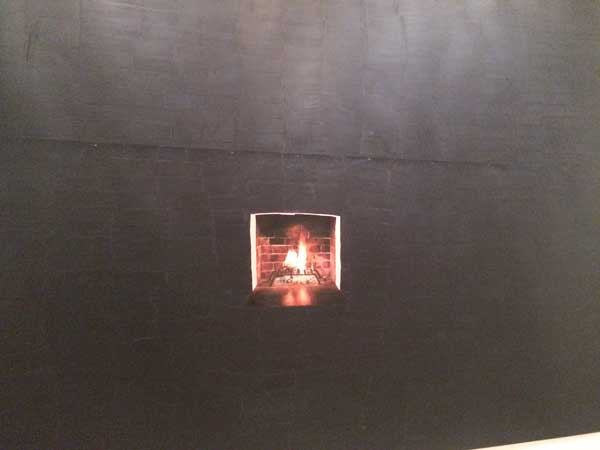

“I see,” I said, as we walked deeper into the eponymous exhibit, which began on September 25, and lasts until March 19, 2017. In another room, we found a welcome burst of color: Khedoori’s two alluring paintings of fire in brick hearths glowed at us with bouquets of gold, black, and red. In one of the dyad, Untitled (white fireplace) 2005, she surrounded the flames with the same drabness as that stranding the chair and the stadium. In the other, Untitled (black fireplace) 2006, Khedoori painted the titanic margins with pitch-dark oil paint.

“I like that one,” the guard said, about the black-bordered work.

“Why?” I asked.

“It’s cozy,” she explained.

In the final gallery of the show, we saw that Khedoori had broken style: She painted smaller canvases and filled them in nearly or entirely. Untitled (Clouds) 2005, held a gray-and-white thunder cloud that took up 2/3 of the paper. Untitled (black squares) 2011-12, bore a multitude of tiny mother-of-pearl-hued squares, like a pixilation, or fine bathroom tile. A winter woodland occupied Untitled (branches I) 2011-12, and a leafy branch crowded Untitled (leaves/branches), 2011-12.

“What’s your name?” I asked.

“O’Shikeya Williams,” she replied, smiling.

As of this writing, Williams has been looking at Khedoori’s negative space for weeks, and still finds in it not only a testament to female ambition, but also a cause for rejoicing. It does not seem likely that everyone given the job of absorbing Khedoori’s difficult negations would have such a reaction. It would take patience and tenacity to see Khedoori’s something in her nothing.

Khedoori is Iraqi-Australian, attended UCLA, and moved to Los Angeles in 1990. When the MacArthur Foundation awarded her their famous grant in 2002, its judges described her fin de siècle drawings as “quiet, reticent works [that] . . . convey a sense of mystery and invit[e] the viewer to speculate on their meaning while appreciating their serene beauty.” And in its ad copy for Khedoori’s exhibit, LACMA tells patrons that museum officials gave her a show to “contribut[e] to the rapidly growing recognition of the work of women artists.”

That is to say, the MacArthur folks remain baffled by Khedoori’s work, and LACMA detects in her oeuvre an opportunity to participate in a feminist art trend.

Experts talk and talk and talk. Parmenides said that nothing cannot exist (“What Is is; for it is to be,/ but nothing it is not”), and Albert Camus took the void for granted, saying that it “stung like fire.” I contemplated Khedoori’s absences and presences for an hour, went home, researched ancient philosophy and French existentialism on the question of Zero, and devised a theory that Khedoori has traveled backward in philosophic time, moving from the emptiness of modernist absurdity to the cozy abundance of a golden age.

But Williams teaches us the more important interpretation, which holds that negative space will claim you unless you fill it yourself. Hers is a kind of endurance criticism, hard-won by the task of guarding artworks as if they are more valuable than people, and, as a consequence, staring at them for hours at a time. Contemplating art under such circumstances teaches the watcher if the work is really worth something or not. Williams gives it value by approaching it with joy and curiosity, and seeing in it the ambitions of Khedoori, a woman artist who cracked an art-world code by taking the rapidly growing nothing it apparently would otherwise offer her and making it her own.

O’Shikeya Williams

LACMA is lucky to have an employee such as Williams and should encourage her sight and gift, which was offered to me with such generosity and illuminated a beautiful show that does not yield its messages easily.