Mari Evans’ poem, “I am a Black Woman” was resurrected through the “Passion Power Prayer” exhibition at Band of Vices, featuring abstract paintings by Lisa Diane Wedgeworth. With a singular vision her works extend an invitation, as in The Matrix (1999): to take the blue pill where ignorance will remain bliss or the red pill, where the truth is revealed. I chose the red pill—metaphorically speaking—and was born again.

A first reading of these works courageously suggests that the various hues of black—whether monochromatic, transparent or opaque—are not mediated, compromised or negotiated. For example, Embracing (Self Portrait as a Levitating Triangle) (2020) depicts isosceles-shaped spikes ascending through a gray whirlwind sky as if being raptured. The kinetic power presented asserts an unyielding protest, defying the belief that abstract suggestion is unknowable. The corresponding work, Accepting (Self Portrait as a Levitating Triangle) (2020) pulses with identical style. However, the scalene-shaped spike is now descending. Wedgeworth’s color choices correlate to the vibrancy of Kerry James Marshall’s acrylic works.

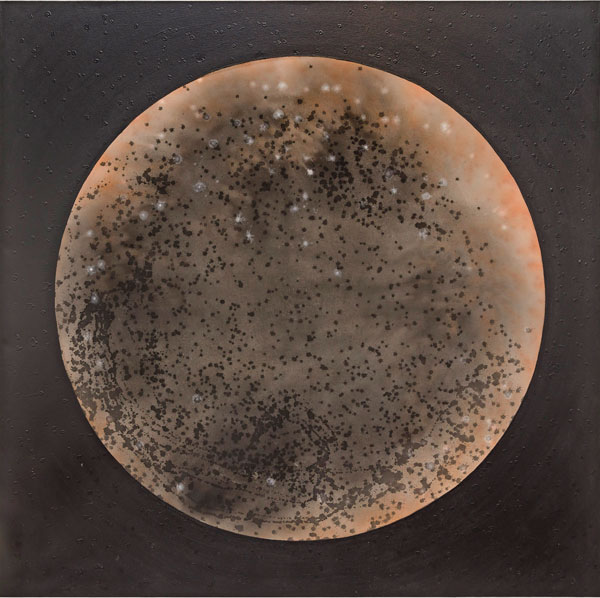

Brown But and Beautiful (2014) is a similarly themed acrylic on canvas work alluding to self-celebration. A background square, coffee-brown, surrounds a tan, moon-shaped sphere sprinkled with dark freckles. Wedgeworth again demonstrates value and beauty within simplicity by whispering with abstraction. This work’s background parallels the acoustic absorber panel and acrylic paint on canvas strategies of Jennie C. Jones.

Lisa Diane Wedgeworth, Brown (But) and Beautiful, 2014. Courtesy Band of Vices.

In her Days and Nights of a Confident Woman (2014) Wedgeworth composes a grid of various levels of Blackness—ebony, licorice—and allusions to the heavenly through dark renderings of celestial bodies, waxing and waning, evoking the moon as a feminine symbol. The shape-shifting nature of each image suggests the inevitability, ambiguity and unpredictability of change, and the conception of feminine value and power. With allusions to earlier Black women artists who worked in mixed media—Dinga McCannon’s Revolutionary Sister (1971) and Out in Front (1982) by Emma Amos.

Wedgeworth’s intentional refusal to aesthetically code-switch is revealed in this body of work. She instead enriches the discourse surrounding Black women artists like Kay Brown, Valerie Maynard, Faith Ringgold and Betye Saar, who seized their creative destinies amid a field tattooed with selfish patriarchy. Ultimately, her artworks paraphrase James Brown but instead say “Paint it Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud!”

0 Comments