Simone Leigh’s presence at the 2022 Venice Biennale was monumental: Her sculptural contributions to the main exhibition garnered a Golden Lion, while her solo show for the US national pavilion generated headlines around the world and lines around the block. In the context of that venerable site—and particularly in terms of Biennale curator Cecilia Alemani’s focus on global feminist surrealism—Leigh’s engagement with Western art history and juxtaposition of canonical and vernacular materials (bronze, gold and ceramic paired with straw thatching, wire and cowrie shells, for example) achieved a profound aesthetic impact and delivered a searing postcolonial critique.

Leigh’s blending of ancestral legacies and diasporic modernity; her infusion of personal perspective into a broader conversation on feminism, race and oppression; and her frankly magical way of crafting shimmering, beckoning, impassive yet impassioned objects of exquisite beauty are leveraged to excavate a dark set of histories. All of that power and grace was on display in Los Angeles this summer when her post-Biennale traveling survey, which orginated at ICA Boston and includes selected works from Venice, finally arrived. This local iteration was shared between two institutions—LACMA and CAAM—each with their own cultural directives and architectural and historical contexts to work with.

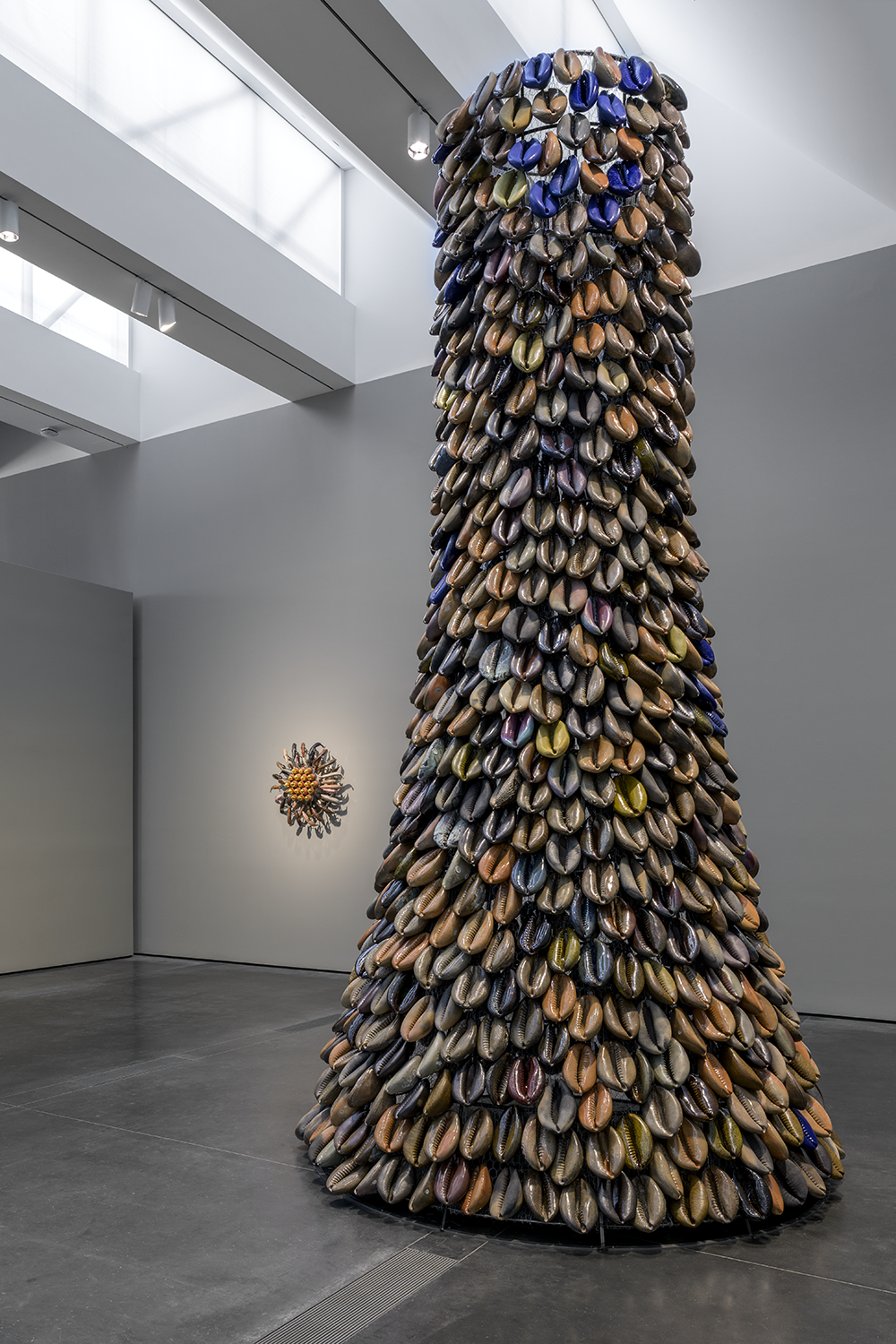

At LACMA, whose mission is to present an expanded global art history, a pair of stoneware Sphinx statues (both made in 2022, one of which appeared in Venice), rested on the floor framed by wide windows and a distant palm, adjacent to a reflecting pool—an inspired curatorial choice. Leigh reclaimed the mysterious feminine guardian energy of the Sphinx in ancient North African mythology while infusing the figures with alluring physicality, activating site-specificity to confront, rather than adorn, a seat of modern cultural power. Untitled (after June Jordan) (2024) is a monolithic 16-foot tower crafted in steel, hex mesh, stoneware and porcelain in the form of hundreds of large, richly glazed cowrie shells—a recurring motif that acts as a symbol of bounty, wealth and fertility and illustrates her evocation of ancestral matriarchy in imagining a more nurturing future.

Simone Leigh, Cupboard, 2022. Photo: Timothy Schenck. Courtesy of the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery. © Simone Leigh.

While LACMA’s curatorial eye is cast in the service of a wider survey, CAAM’s is more closely attuned to renovating the canon to include previously marginalized voices, foregrounding especially the richness of the African American cultural presence in Los Angeles. The monumental Cupboard (2022), with its 11-foot-tall, chapel-like figure of stoneware, raffia and steel armature, had its own intense gravitational pull; its dazzling counterpart, the gilded, seven-foot bronze Cupboard (2022) was installed outside the museum’s entrance. Both of these works, which exemplify Leigh’s affection for pre- colonial mythologies, spiritual practices, materials and techniques, were exhibited to wide acclaim in Venice. Inside the gallery,poignant earlier works relayed more biographical narratives, and two video pieces and a ceiling-mounted light sculpture made explicit connections to contemporary popular culture.

The choice to distribute the show’s relatively small number of works (about 30 pieces in total) across two locations also meant that each installation was relatively sparse, and all of the galleries were dramatically low-lit, some by the flicker of video projections, creating a meditatively paced pathway through the rooms. With such uncommon power, and its command of all the requisite visual languages, including its unapologetic embrace of beauty, the work occupies all of these spaces—literally and figuratively—even as it continues to open new ones.