Kinetic Art, like so many postwar movements, arose simultaneously in several disparate corners of the world, coalesced in the late 1950s and early ’60s, and derived from prewar tendencies whose revolutionary aesthetics and idealistic spirit seemed appropriate to a world rebuilding. Paris, at that point rivalling New York for art-world preeminence, served as the hub of the Kinetic Art movement, but its practitioners were as likely to be found in Italy, New Zealand and various South American countries. Indeed, the Latin American contribution to Kinetic Art, whether made in Paris or in places like Caracas, Buenos Aires, and Rio de Janeiro, was key to the movement, in terms of both innovation and sheer volume of work.

This is the case the survey “Kinesthesia: Latin American Kinetic Art 1954-1969” makes clearly and persuasively. It also makes a case, somewhat less compelling, for the art’s enduring relevance and effect. Its charm does maintain, and several bodies of work here evince startling imagination and/or aesthetic strength that transcends the creaky spectacle of mid-century technology. Other oeuvres on view, however, seem as dated as lava lamps. Still, curator Dan Cameron was right to include the lesser lights. They connect the historical dots that describe a practice of great historical significance—more significance, in fact, than we now give it credit for. These blinking bulbs and whirring motors may seem quaint today, but so does a telegraph key and a steamboat.

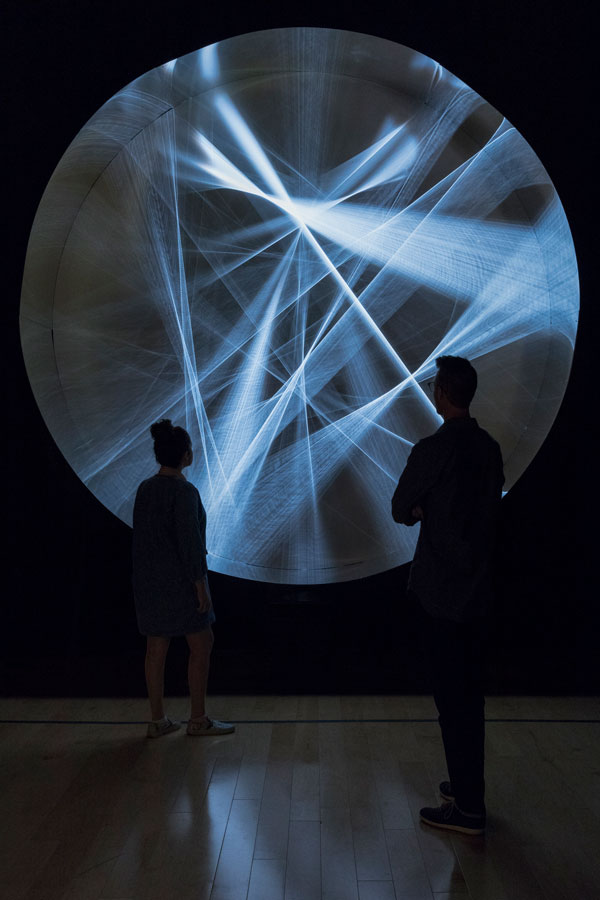

That said, there is plenty to feast one’s eyes on here, especially in several rooms dedicated to ambitious spatial-installational concepts. The work of only a few artists, it should be noted, comprises the entire exhibition: rather than survey the South American Kinetic movement, Cameron decided to gather exemplary objects into nine micro-solo shows. This robs his historical argument of some sinew, but gives it depth.

Installation view of Gyula Kosice’s Hydrospatial City, 1946-1972, photo by Lance Gerber, courtesy Palm Springs Art Museum.

Everything modern and magic about this art comes alive in those installational rooms. Brazilian Abraham Palatnik’s drifting, mesmerizing projections—like clouds of color attempting to coalesce into paintings, for instance, are best viewed in a space equipped with seating. The Hydro-spatial City that Argentine Gyula Kosice worked on between 1946 and 1972 also requires a darkened room, consisting as it does of glowing islands of eccentrically formed clear acrylic—a poetical fantasy of post-earthly habitation. Venezuelan Carlos Cruz-Diez’ Chromosaturation (1965/2010), on the other hand, dispels darkness with its three adjacent spaces each filled almost haptically with a different color (blue, red, green), so that one becomes aware of the differing psychological and even physiological impacts of the discrete colors.

Cruz-Diez is also represented by less radical painted and wall-hung work. Wall- and shelf-mounted paintings and objects by his countryman Jesús Rafael Soto, as well as by Argentine artists Martha Boto, Julio Le Parc, Horacio Garcia-Rossi and Gregorio Vardanega, are also displayed—all handsome and intriguing but, in comparison with the rooms described above, a bit tame. More impressive are the early geometric paintings and later quasi-architectural proposals of Venezuelan Alejandro Otero, whose imaginative deployment of modular forms propose a whole new sense of space, as well as habitation, for a species about to venture off the planet.

0 Comments