Kim Schoenstadt’s approach to visual art conflates two and three dimensions, crawling up the wall and on the floor, gelling into freestanding objects even as it elaborates on a kind of drawing-in-space that seems at once to leak from and to enmesh the sculptural, even functional, constructions. The lucidity, even sobriety, of Schoenstadt’s style gives it an elegant sense of restraint and almost musical order while its vibrancy and barely-contained voraciousness, akin to that of a climbing vine, comes from her expansive and unpredictable use of space. She is a tidy conceptualist but an explosive formalist, and thus operates close in both spirit and reason to the discipline she at once idolizes and satirizes, architecture.

Schoenstadt has become well known for her quasi-architectural fantasies, elaborations (in various media and formats) on usually late-modern architectural monuments and unfulfilled proposals that suggest a built landscape in the process of growing out of hand. Sometimes such space-age domiciles and auditoria double back on themselves comically, other times they burgeon like tumors. Lately, Schoenstadt has been focusing as much on the energy of growth itself as on the architectural shapes she distorts and distends, filling vast spaces with what seem virtual-reality geometries plucked from video games and other digital nightmares. In comparison, the five “Sightline Constructions” comprising this recent gallery show feel rather decorous, if ominous in their very discretion.

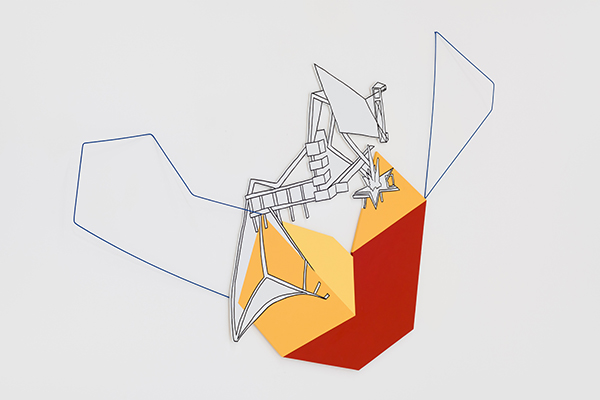

Kim Schoenstadt, Book Truck No. 1, 2015

courtesy of the artist and Chimento Contemporary

photo: Ruben Diaz

Only one of the exhibited “Sightline Constructions” is freestanding. But, with certain key elements extending off the wall in torqued distortion, the other constructions also break the picture plane and work in time, changing their internal relationships as the viewer walks toward and past them. They all contain distinct components, the aforementioned linear elements, panels of color, and Schoenstadt’s traced approximations of extant architecture. These excerpt from sources as varied as Oscar Niemeyer’s government buildings in Brasilia, World’s Fair pavilions, fantasy houses from Hitchcock films, and even more fantastical structures quoted from kids’ cartoons. Schoenstadt favors the space-age eccentricities of anti-International Style late modernism, but she finds brutalist rhythms and Googie curves in more recent architectural projects as well. Such a meld, and such an approach to melding, betrays Schoenstadt’s admiration for the sources she pillages and bricolages; while witty enough not to seem fan-girl, her mash-ups clearly seek to focus on and extend an aesthetic, perhaps ethic, of grace and surprise she identifies in her material.

Schoenstadt’s is clearly a hands-on approach, but one also powered by deep research and active intellection. She invited us into this process, almost self-consciously, with Book Truck #1, a rolling bookshelf stocked with books new and old, fictional and academic, small and large, each one lent to the truck by various friends and colleagues of the artist – “whatever book they are currently excited about or using as research,” as she claims. It was an eclectic and heady selection that invited dreamy perusal – and that waxed nostalgic for the objecthood of the book much as Schoenstadt’s “Sightline Constructions” wax enthusiastic for the almost immaterial fantasy of crazy buildings.