What do Ed Ruscha, John Baldessari, Richard Prince and Jeff Koons have in common? If you answered all are old white-guy artists that make lots of money with their art, you would have answered correctly. But they have another thing in common. They are all NOT represented at the “State of the Art” exhibition at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, a fairly new art institution founded by Walmart heiress Alice Walton.

Though the subtitle of the show: “Discovering American Art Now” wouldn’t necessarily include the above-mentioned old-hat mega art stars, Crystal Bridges President Don Bacigalupi and Assistant Curator Chad Alligood, who conceived and curated this show, made it a point to search out unrecognized artists making art in America and purposely skip the national art centers such as Los Angeles and New York City.

I was attracted to this show for many reasons. Foremost, it provided an opportunity to travel “back home,” as I grew up in that part of the country. Back then, in the late ’70s, Bentonville (home of Sam Walton, thus Walmart) was basically a one-horse town, surrounded by rolling hills and thick forests with brooks and rivers. The one movie theater was the only connection to any mainstream culture. The nearest art museum or art gallery would most likely be in Tulsa, Oklahoma, or Little Rock, Arkansas, and you can bet your bottom dollar it was Western art (meaning Cowboy art). Being fresh out of high school I was interested in pursuing an art career, but majored in Sociology instead at the nearby University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, thinking I could never make any money in art.

I later became a public school art teacher in Oklahoma, and I can attest that this would be the thinking of most of Americans embarking on an art career, especially 40 or so years ago. That notion, however, does not prohibit people from making art (I ended up majoring in art after all). All those little towns and cities in between the East and West Coasts have colleges that offer art classes with art professors from all over (my drawing teacher at Fayetteville was a graduate from Yale). I’m fully aware of the limitations of those middle-American cities—most are void of cultural institutions such as museums, theaters and concert halls. But there will always be community playhouses, piano lessons to procrastinate and blue ribbon prizes for the best-pickled eggs. And there will be art being created.

This is the thinking of curators Bacigalupi and Alligood—that there is art out there (and good art), not being seen by the general public. So they traveled over 100,000 miles throughout our great nation, visiting around 900 artists’ studios. They devised systems to keep them on track and narrow their search, for instance a mnemonic tool of three descriptive words for each artist, i.e., “psychotropic video travelogues.” The result? A mixed bag in my opinion, but I’m not sure I’m the audience they had in mind, and that is the issue here with this show.

I’ve become an art snob I’m afraid. “State of the Art” somehow ended up being “Contemporary Art Loves You”—the reverse of John Water’s proclamation: Contemporary Art Hates You. The works on display say, “My kid couldn’t do that,” rather than the opposite, which often means you’ve stumbled onto some real cutting-edge art. But that’s not to say the art here doesn’t deserve merit. There were some real gems and I will highlight those, rather than focus on the oftentimes too Bibley-Beltish art for my taste and way too much Photorealism.

Upon entering the exhibition, the interactive installation by Minneapolis artist Andy DuCett includes real live local mothers. The Bentonville matriarch that day was cheerful, helpful and kept in character with her welcoming smile and eagerness to offer motherly advice or even explain DuCett’s intentions with “Mom Booth.” This was a fun piece, but maybe a little too cute, but a good start nonetheless. We then entered the galleries through a crocheted walkway by Brooklyn artist Jeila Gueramian. This was impressive enough and could easily be compared with artist Liza Lou—with colored yarn covering the surfaces instead of colored beads—with a little Mike Kelley thrown in.

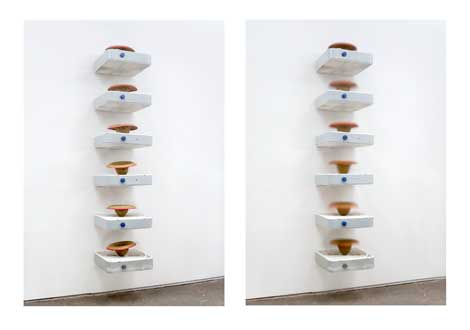

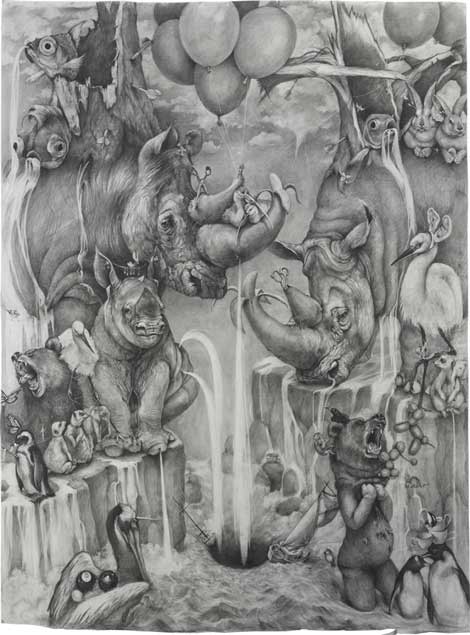

These two installations served as the introduction to a sprawling exhibit of 102 artists’ works spanning the United States from ages 24 to 87, comprising the gamut of mediums: painting, photography, paper, installation, sculpture, video, ceramics, fabric and glass. The next piece that caught my attention was Stack (2013), a funny one-liner by Detroit artist Hamilton Poe. A row of box fans were mounted on the wall horizontally (where they jut out of the wall), spaced evenly vertically, reminiscent of Donald Judd’s stacked rectangular sculptures. I’ve seen many versions of this now (might this be a college art assignment?). Sombreros were placed atop the operating fans, appearing to dance in mid-air. Santa Monica, California artist Adonna Khare’s large graphite drawing, Rhinos (2014) was simply amazing with its deft draftsmanship and fantastical imagery of animals and plants. The careful attention to detail and meticulous rendering was akin to Los Angeles artist Tom Knetchel, though without the edge. I would have liked to see a little more grit put into these massive drawings.

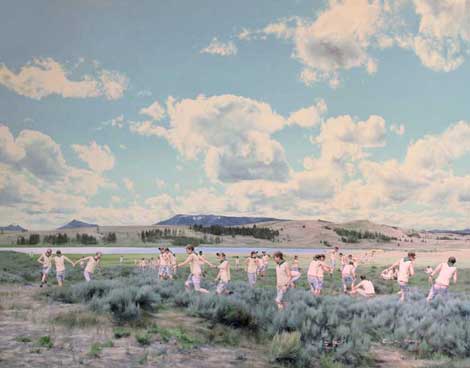

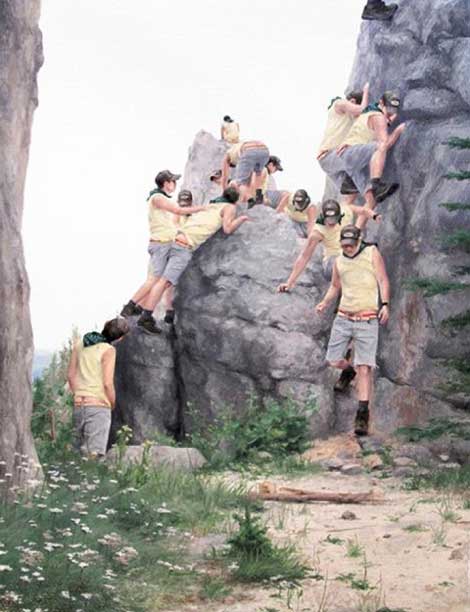

A set of paintings by Cobi Moules from Brooklyn stopped me in my tracks. They were landscapes beautifully painted, populated with figures at play; some in Boy Scout uniforms, some bare-chested in rivers. Soon you realize they are all the same person. Immediately I think of Anthony Goicolea’s photoshopped self-portraits in similar environments. Goicolea’s work has to be a factor in these marvelous paintings. Moules also draws from the Hudson River School, and could certainly be in their class. Another Brooklyn artist, Dan Witz, wowed me with his hyper-realistic mural-sized painting, Vision of Disorder (Frieze Triptych) (2013). The 3-panel painting depicts a mosh pit of young men, seemingly frozen in time, mid-pogoing and shoving. The figures are painstakingly painted, but with expressionist markings, not entirely photorealism (thank you). Los Angeles painter Scott Hess comes to mind, especially with the pained expressions and motionless activity. My favorite though of all the painters (I don’t recall any nonrepresentational painting) was Guy W. Bell’s Cain and Abel (2013). Bell is from Little Rock, Arkansas. His large painting of two dogs (one white, one black) caught up in a ferocious fight in the foreground against a golden vast landscape was remarkable. The paint quality was superb and the complicated narrative of the piece was ambiguous enough to keep me interested and wide open for interpretation.

Onto sculpture, video and installation…tops in originality and execution was Brooklyn artist Jonathan Schipper’s installation Slow Room. In fact this might be the showstopper. I visited toward the end of the show’s run (Thanksgiving week, and the show opened in September). This installation was basically a living room set, complete with furniture, television, rug, end-tables with tchotchkes, pictures on walls. There was a hole on the back wall where all the items in the set were attached to a cable that slowly tugs at them, pulling each toward the hole, thus destroying the item once it collides with the wall. A supreme example of how this installation worked is on the museums’ website where a time-lapsed video catches the action. Although this work’s merit might be in the sheer execution, it also kept the audience engaged with the “home” aspect and the issue of time and mortality.

Another powerful installation was Southern Californian artist Danial Nord, whose work ends the exhibition. You enter a darkened room with specs of video light peeping through overturned cages of large unidentified shapes. TV sets flicker among debris with a vaguely familiar soundtrack. Suddenly you realize it’s audio snippets of the Mickey Mouse TV show eerily sounding like Nazi rallies, and might the cage have mouseketeer ears? The object is so big (and we don’t have room to back away) that it’s hard to tell what it is, but when our eyes begin to adjust a silhouette of the reclining mouse becomes visible. Disney is always a subject rife with controversy, and Nord’s video installation shows his prowess with video and sculpture. Finally, Peter Glenn Oakley’s marble sculptures were completely insane, accurately replicating mundane objects such as stacks of Styrofoam take-out cartons, music cassette tapes and a sewing machine. The Pop sensibility with each object chosen to carve out of marble served the artist’s ability to display his adeptness with his material, yet taking the Old Masters medium to another level.

Which brings me to the presumed thesis of “State of the Art.” Most of these artists won’t be showing in the copious biennials, triennials, MOCAs and art fairs around the world, but now they get their 15 minutes of fame in Bentonville. And does that matter? Deep down it might. Making art in your studio is one level of creating, but what then? Artists create because they have something to say. The artists in “State of the Art” are clearly talented and dedicated artists, but most of the art is not breaking any boundaries. That said, “State of the Art” is successful in what it set out to do, and a sampling of what’s out there today. The exhibition was certainly eye-opening and a joy to experience, but I found myself harkening and comparing work to what I’ve now been exposed to. I feel like the curators played it a little too safe and went with the crowd-pleasers.

Though, Crystal Bridges is a diamond in the rough and is a credit to that area. The early American art collection is one of the finest in the country, and their acquisitions of contemporary art is fast-growing. I know this would have been a valuable venue to visit when I was growing up in the Heartland. And who knows, maybe I would have bumped into native Oklahoman Ed Ruscha.

For more images visit the excellent website of this show: http://stateoftheart.crystalbridges.org

State of the Art: Discovering American Art Now ends January 19, 2015

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

600 Museum Way, Bentonville AR, 72712

479-418-5700, www.crystalbridges.org