Historically, art and politics have often been intertwined. In Dada, Futurism and Russian Constructivism, as well as in some Conceptual art practices and works by individual artists such as Sister Corita Kent, text and image have emblazoned artworks with calls to action or commentary on current politics. Diagrams and mapping trajectories, either personal or more universal, have also been explored by artists such as Mark Lombardi and Danica Phelps. Keith Walsh is a Los Angeles-based artist and activist whose work maps the transformation of political attitudes and relationships of activism in the US and Los Angeles.

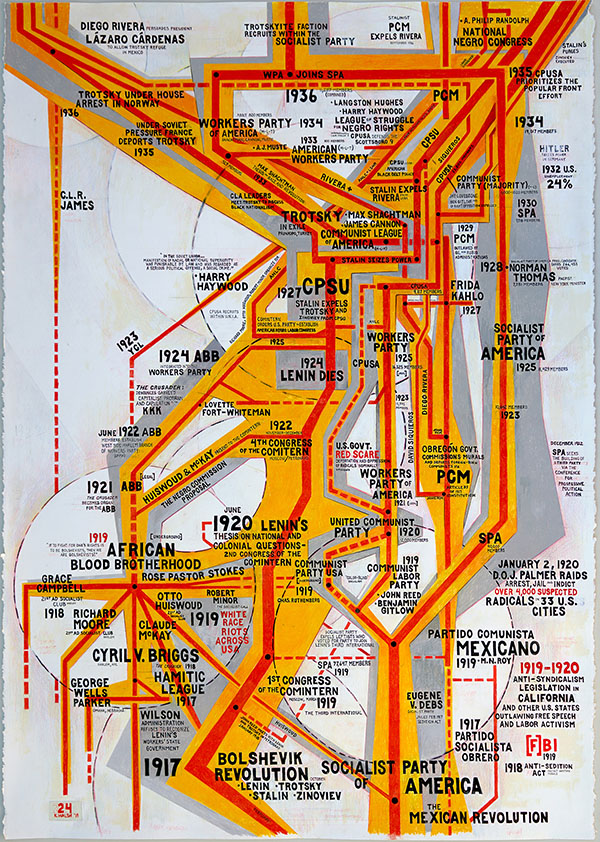

His labor-intensive drawings incorporate flow charts, timelines, bold graphics, geometric shapes, and hand lettering to trace political movements and causes over time. For example, LA Socialist Network 1950–2019 (2020) is a rhizomatic diagram connecting different politically leftist organizations and people working in various socialist or communist groups. A series of overlapping red and pink vertical and horizontal lines intersected by black texts and occasional hand-drawn images culls together a history that might otherwise disappear. Radical Power and Uncertainty 1917–1937 (2019) similarly chronicles communism in the Soviet Union, the USA and Mexico, and includes membership numbers and African American contributions. Walsh’s drawings are thoroughly researched, and the visual and textual information is often organized to correspond with the political leanings of the various organizations. As Walsh states, “If an organization trends toward a more politically conservative ideology, its line will move to the right of the visual field.”

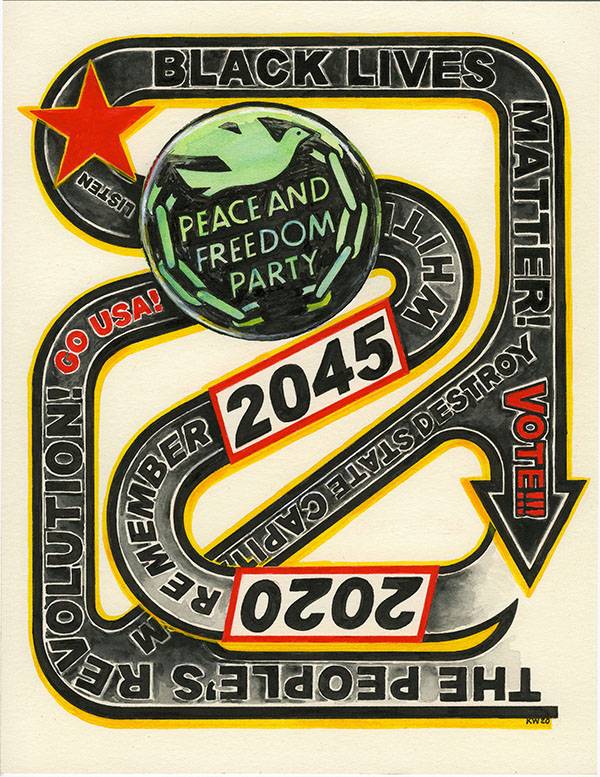

Many of Walsh’s works could function as political posters and calls for action. Some speak to the present: 2020 Remember 2045 (2020) celebrates the Peace and Freedom Party and Black Lives Matter, whereas Comrades for Comrades (2020) links the historical to the now. To fully understand and appreciate many of Walsh’s explorations requires a patient and thorough reading of the texts within each work. However, Walsh also includes pieces with minimal text as in HUAC/California Legislature, September 1965/OP Version (2019) where black-and-white concentric rectangles block out any identificatory or incriminating information. This formally elegant work recalls Jenny Holzer’s Redaction Paintings.

Keith Walsh, Radical Power and Uncertainty 1917-1937, 2020. Courtesy Rory Devine Fine Art.

Walsh’s most recent drawings are a series of colored pencil and graphite works on paper. Here, rows of thin concentric rectangles in specific families of color surround individual words or phrases. Arguments (Black and Blue) (2020), states in capital letters: “as time marches onward // the people will find the arguments // voiced by // Ronald Reagan // to be less and less // persuasive.” In Belief (Malcolm X) (2020), drawn in oranges and blues, one reads “it’s impossible // for a // white person to // believe // in capitalism // and not // believe // in racism.”

Walsh’s exhibition explores the graphical power of words and images and how they can work together as both art and political calls to action. He is invested, historically and contemporaneously, in the struggles for liberation and equality, and able to communicate through his art the urgency of these messages, both past and present.