Post-minimalist Keith Sonnier, who passed in 2020, was too prominent a figure to fall into the shadows, as have so many of his contemporaries. But given his striking originality, restless inventiveness and impact upon a broad range of peers and younger artists, Sonnier’s star should have shone even more brightly than it has since the ’70s. This exhibition seeks in its own modest, intimate way to rectify that oversight—not by accruing and displaying a mini-survey of Sonnier’s own work, but by signaling the influence he has had specifically on younger artists. What the show’s title, “Live In Your Head,” proffers is not so much the power of his own work but the artist’s enduring mark on subsequent art in three dimensions.

This might make it sound as if painterly values were foreign to Sonnier’s practice. Just the opposite is true: He treated his shapes and materials as marks and amplified their coloristic presence until the elaborate structures he built could be looked at as drawings and paintings in space. There’s nothing like neon to juice such a tendency, and Sonnier is perhaps best known as the wild man of American neon art. Neon was a fairly prevalent device in the art of Sonnier’s era and just before, but artists like Chryssa, Stephen Antonakos and Martial Raysse engaged neon in a highly decorous, and formally rigid, extension of Pop Art. Sonnier, by contrast, echoed the medium’s expansive pioneer, Lucio Fontana, in filling headspace as well as exhibition space with erratic glowing elaboration. (Did Sonnier know Fontana’s early neon work when starting out himself? Probably not, but I wouldn’t be surprised to find otherwise.) His close-at-home model was, of course, Dan Flavin. But Sonnier’s approach from the outset was, if anything, a gentle rebuke to Flavin’s purity even as it was a warm embrace of his palette.

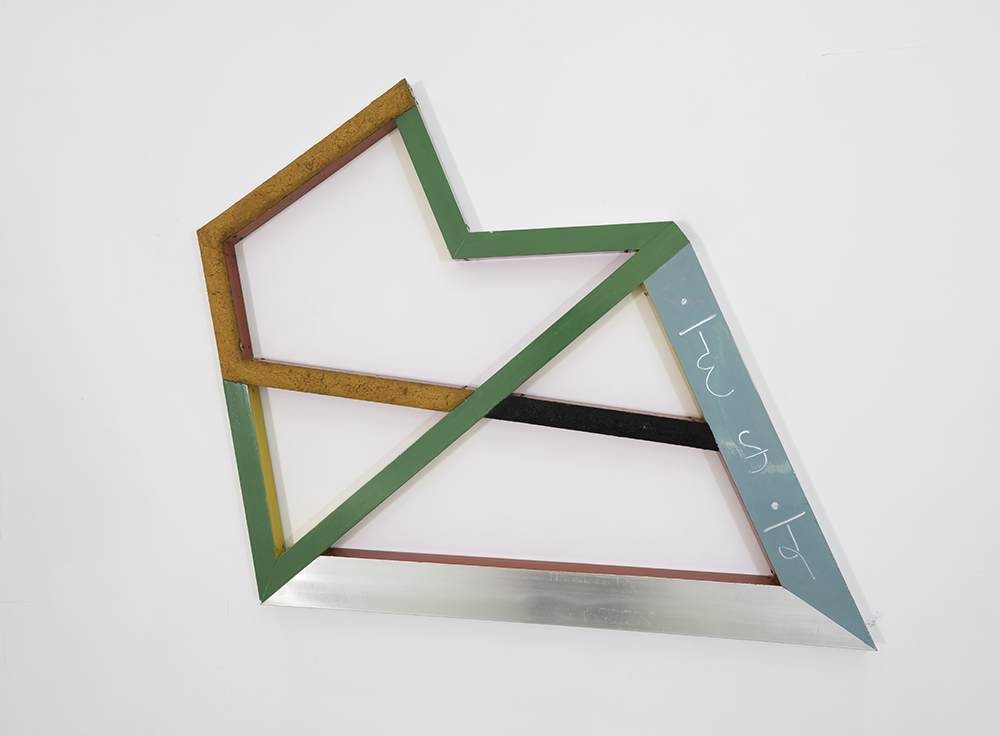

Keith Sonnier, Mavo II, 1981.

The three works in “Live In Your Head,” from diverse points in his career, do not sate a Sonnier jones, but in context they do demonstrate his appeal to younger artists in the show such as Jessica Stockholder and Ann Veronica Janssens, whether or not they use neon in their work. Go wide, Sonnier encourages his fellow artists, and don’t be self-conscious about what you use and how you use it. Let it fly. Art is shape. Art is stuff. Art is light—yes, at one and the same time. Sonnier had an almost magical way of animating his pieces, and the supporting cast here, reflecting his genius, has found its way to a similar vitality. Right now is a good time for sculpture, and, as the show reveals, Keith Sonnier is one reason why. The other laudable artists here include Nabilah Nordin, Madeline Hollander, Kennedy Yanko, Terence Koh, Maya Stovall, and, for some reason, Sonnier’s co-generationist Mary Heilmann, represented by a tiny little darkly golden canvas—peculiar, endearing, and so out of place that it’s perfectly in place.