The post-pandemic era can offer rewarding challenges, as I found out when engaging in my first Zoom interview. I spoke with painter and educator June Edmonds on the occasion of her current 40-year retrospective at the Laband Gallery, Loyola Marymount University, and a simultaneous solo show at Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

Edmonds appeared on screen with a welcoming smile and friendly brown eyes that peered through rectangular glasses. A pair of circular sepia earrings complemented her double-crescent semi-Afro hairstyle with its curled strands.

When asked about her early years, she fondly recalled, “My mom was a teacher and she loved to draw. She would sit by the phone and draw profiles of people, and I enjoyed collecting those little sketches.” Her mother also took Edmonds on formative trips to the Huntington and LACMA.“When I was teenager,” said Edmonds, “she brought me to see the ‘Two Centuries of Black American Art’ show (LACMA, 1978). These works by African American artists had a profound formative impact upon Edmonds, as did a 1989 trip to Washington DC, where she viewed a Post-Impressionist exhibition.

June Edmonds in her studio, San Pedro CA, August 2021

Edmonds related that in her undergrad education in art at San Diego State, “Joy Shipman was super-supportive, and so was Patrick Cauley. I attended Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia. Graduate school was very challenging because color was not in—especially for a student who wanted use color in the way that I did, but Stan Whitney was very helpful.”

Edmonds described two significant events that inspired her to become a public artist—first a trip to Mexico City: “We arrived late at the Museum of Anthropology and we could not get in, so this taxi driver offered to give us a tour and showed us all the important murals that we learned about in art history, and other works that I was unfamiliar with. It was those works made in Venetian glass mosaic and the mural by Jose Chavez Morado that most moved me.”

The second such event was an exhibition of public art for MTA created by artists of color that Edmonds attended in downtown Los Angeles. This was an opportunity to see proposals (public art models) by Willie Middlebrook, Sandra Rowe (the first Black woman to be awarded an MTA grant), Richard Wyatt Jr., John Outterbridge and Charles Dickson—and to meet those artists.

Metro Blue Line, Long Beach Pacific Station, (detail) public art by June Edmonds, venetian glass mosaic,1995

Edmonds remembers, “I was just working, trying to pay off my student loans. I didn’t know where to find such a community.” However, Edmonds began to attend artists’ talks and describes one given by Willie Middlebrook: “I was blown away by his work, blown away to see this Black artist with so much talent, so much confidence to be able to express what he was doing.”

In 1995, Edmonds was selected to create a Venetian glass mosaic for the Metro Blue Line, Long Beach Pacific Station, making Edmonds the second Black woman to be awarded an MTA grant.

In 2010, when Edmonds was beginning to focus on abstraction, she was invited by Kathy Gallegos, director and founder of Avenue 50 Studio, to have a solo show. This was a turning point in her journey as an abstract painter. “I love the freedom that it gives, how an artist can create their own language, and how abstraction can even communicate on a spiritual level,” said Edmonds, emphasizing the importance of abstraction to her practice.

In 2017, during an artist’s residency in Paducah, Kentucky, Edmonds began working in acrylic paint rather than her usual oils. She explained, “[The residency] was only for a month, so I needed a medium that would dry quickly.”

June Edmonds, photo by Chris Wormald.

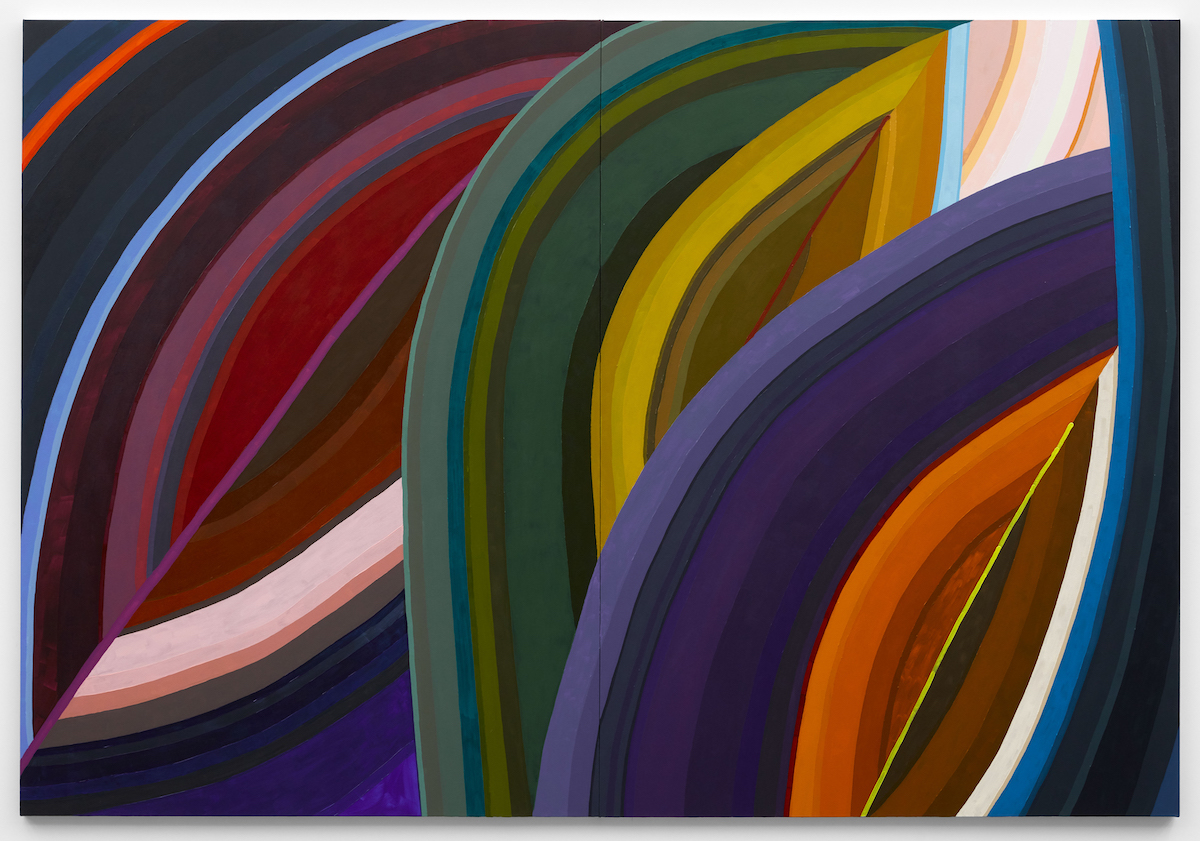

She showed me her sketchbooks and described how she uses colored pencils to work out the composition and its various hues. Her process involves using overlapping circles to intensify negative and positive space and create other shapes that possess spiritual and feminine connotations: “the shape of a seed, the shape of a leaf implying growth, the shape of a vulva symbolizing life, and also the shape of a shield.”

Edmonds stated that she had a dream of four Black draping flags that inspired the “Allegiances and Convictions” flag paintings that were unveiled at the Luis De Jesus gallery in 2019. “The symbolism was too strong to let go of, and I wanted to use neutral browns with various values that represented skin tones.”

“Black people… ” Edmonds concluded, “No matter what is said to us, no matter what attitudes are brought to us, we have this amazing sense of ownership of where we are.”