It’s been said that the first half of the 20th century was Picasso’s and the second half, Duchamp’s. The transition from modernist painting to today’s mixed-media conceptualism is in large part due to a 1963 Duchamp retrospective at the Pasadena Art Museum. The show arguably influenced American art as much or even more than the 1913 Armory Show in New York, which brought the gospel of modernism—memorably symbolized by Duchamp’s cubo-futurist painting, Nude Descending a Staircase, mocked by one critic as “an explosion in a shingle factory”—to America. Four years later, Duchamp would scandalize the modernists as well, with his subversive Fountain, the ‘readymade’ urinal reflecting Duchamp’s scorn for “retinal” visual pleasure as a criterion for aesthetic judgment and his opinion that plumbing was America’s true contribution to the world. By 1963, American artists, jaded with what they saw as Abstract Expressionism’s wallowing in emotion and subjectivity, were ready for a more cerebral approach, and found inspiration and precedent in Duchamp’s provocative work from a half century earlier.

Julian Wasser

Duchamp smoking Cigar next to Bicycle Wheel , Duchamp Retrospective, Pasadena Art Museum, 1963, © Julian Wasser

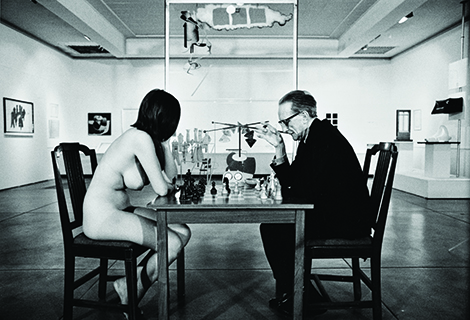

The Pasadena show, curated by Walter Hopps, is now symbolized by Julian Wasser’s drolly matter-of-fact photograph of a nude woman playing chess with Duchamp, referring both to his scandalous Armory painting and his legendary (though apocryphal) later abandonment of art for chess. (He worked secretly on The Large Glass.) Hunter Drohojowska-Philp writes in Rebels in Paradise: The Los Angeles Art Scene and the 1960s that the woman, Eve Babitz, Hopps’ secret girlfriend at the time, refused to be ignored any longer, causing Hopps to flee from Wasser’s camera. That photo, along with contact sheets from the session (some showing Babitz smiling at the game, and chess master Duchamp temporarily discomfited), solo portraits of the artist with his work, reception shots featuring Larry Bell, Billy Al Bengston, Dennis Hopper, Robert Irwin, Ed Moses, Ed Ruscha and Andy Warhol, forms the core of this show, a commemoration of that watershed event in American art. Some of Wasser’s photos are from the ’60s; others have been digitally scanned and enlarged.

Accompanying the photos in the small gallery are immaculate reconstructions of iconic Duchamp works by Los Angeles artist Gregg Gibbs and others, probably life-sized: Nude Descending a Staircase, The Large Glass, Fresh Widow, Fountain, Rotary Glass Plates, With Hidden Noise, Bicycle Wheel, L.H.O.O.Q., Bottle Rack, and so on. Duchampians will enjoy the Greatest Hits (to which are added a life-sized painted wooden sculpture of the Babitz-Duchamp game), and the show celebrates Duchamp’s influential legacy even if it raises unanswerable questions. Who decides what art is, and how: the artist, as Duchamp said, or anyone in the art world, as critic Arthur Danto said? Does the hand of the artist matter, or are appropriation and the readymade equally valid, especially in the digital era (vide Richard Prince)? And what happens when art and anti-art collide?