At the retrospective “Judithe Hernández: Beyond Myself, Somewhere, I Wait for My Arrival,” mounted by The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture of the Riverside Art Museum, the full spectrum of an artistic career of more than 50 years was on view. Beyond Hernández’s masterful depiction of the figure, which she renders in vivid pastels on paper, a recurring narrative within this expansive exhibition was the artwork’s capacity to redeem and empower the women it portrays. The show was structured by Cheech’s artistic director, María Esther Fernández, into four sections based on her conversations with the artist: “Ni una más: Bearing Witness,” “The Evolution of the Female Archetype,” “Surrealist Landscape” and “Reimagining Eve.” Throughout, the only female member of the 1970s Chicano artist collective Los Four has painted with consistent, uncompromising clarity.

The works in “Ni una más: Bearing Witness” harness symbolically potent imagery to address such issues as corruption within the Mexican government, the United States’ imperialist agenda and the epidemic of femicides that continues to ravage the American/Mexican Border. Soy la Desconocida (I am the Unknown) (2022) speaks to the invisibility of women. An expressionless woman seen in profile floats, eyes closed, amid murky green weeds. Spiraling around her in the water are multicolored stemless flowers, while behind her two birds in flight hover in a forebodingly cloudy night sky. The birds carry a winding pink ribbon on which is strung a burning card with a rose on its face. Hernández’s searing iconography suggests the marginalization experienced by women and the feeling of desolation it yields.

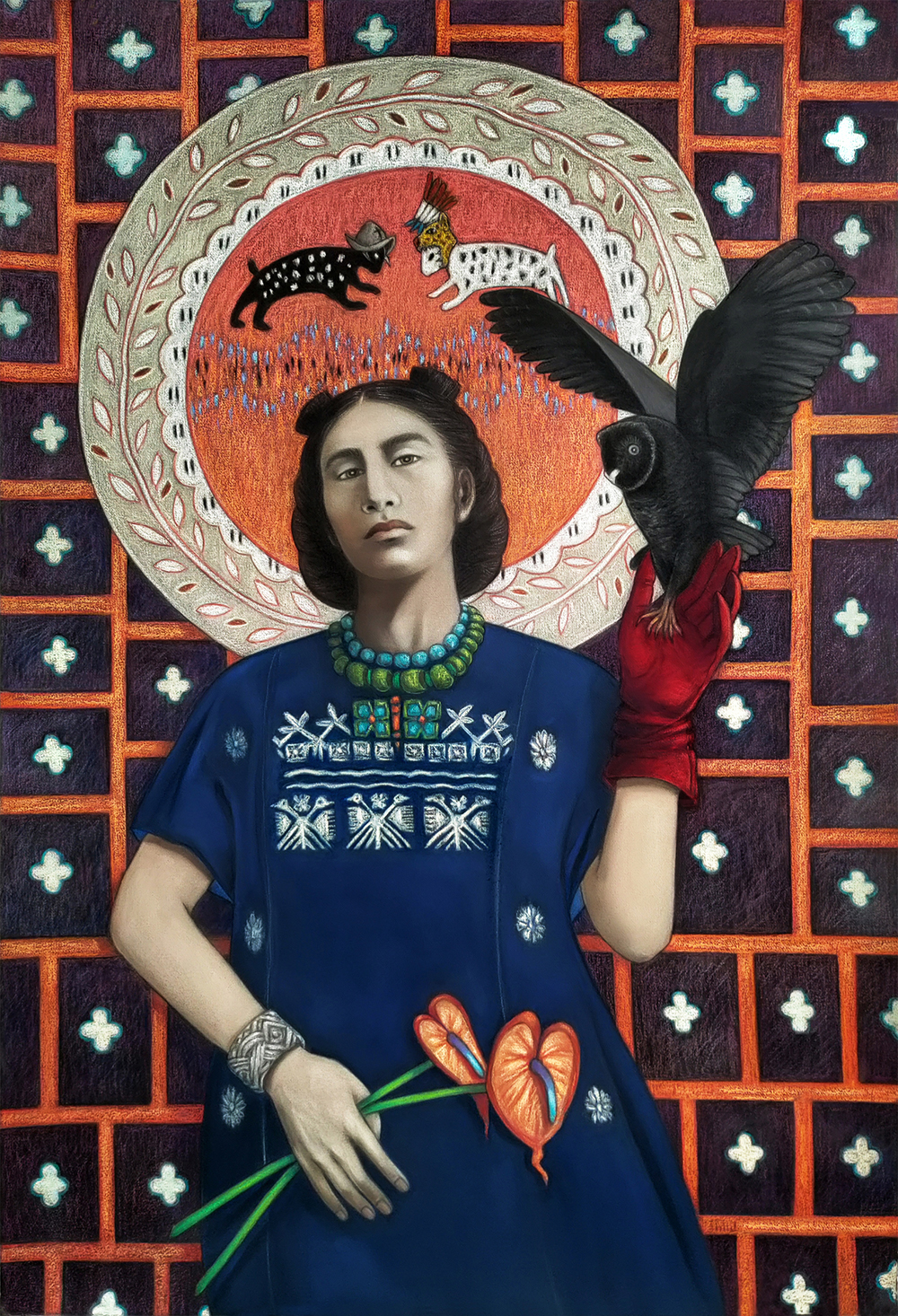

Judithe Hernández, The Defender of Anahuac, 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

The “Reimagining Eve” grouping assaults the traditional, phallocentric interpretation of the biblical creation story. The Seduction of Adam (2010) presents the tightly cropped head and shoulders of Adam, his face caressed from below by two hands, blue and red. A pair of bound purple hands, rope sinuously encircling them like a serpent, reach toward him from above and linger over his forehead; his eyes are closed as if reflecting destiny’s implication regarding free will. And in fact, the end of the rope has transformed into a gold-scaled snake whose flickering tongue slithers just below the subject’s chin, suggesting the correlation between choice and temptation.

The show was enhanced by ephemera that included sketchbooks, copies of Aztlán: Chicano Journal of the Social Sciences and the Arts, a 1974 Los Angeles Times news clipping about the mural painted by Hernández on the wall of the city’s Century City Playhouse and a video interview in which she discusses her early days as a student at Otis College of Art and Design. Collectively, they provided evidence of how Hernández interrogates sexist perceptions of women with her visceral voice. The work she has produced throughout her career has merged into a singular canon, reflecting an artistic journey drawing on the artistic modes of social realism, Surrealism and the Chicano Movement, which has forged a singular personal aesthetic borne of her unique synthesis of religious and political iconography and conceptual tactics.