Your cart is currently empty!

Category: **MAY-JUNE 2024

-

ART BRIEF

The Role of an Art Advisor, Part 2This is part two of an interview with art advisor Wendy Posner, CEO of Posner Fine Arts, an international art advisory based in Los Angeles. Part one appeared in our March/April issue in which we discussed how the role of art advisor is facing the challenges of mega-galleries that have recently added in-house advisory services. In this part, we talk about online sites, such as Artsy, and the auction houses that have now expanded into the art advisory space.

Stephen Goldberg: I understand that you deal with Artsy and other online marketplaces, including Artnet. It turns out they have advisory divisions as well.

Wendy Posner: Yes, they now have advisory services and can locate works for the collectors. With Artsy in particular, we are a subscriber to their marketplace. We have our fine-art business practice on there with artworks for sale. But, we’re also in competition with them. Because if they are looking for an artwork for a collector—let’s say they’re looking for an Ellsworth Kelly—they can go into their backend database, and they have all the information from every gallery that’s on their marketplace of who has a Kelly or has listed him in the past, and they can utilize that data to acquire works on behalf of those collectors. So, there is an unfair advantage because they have relationships with the galleries that are subscribers on their marketplace.

Does it make sense to even deal with them?

For us, we have no choice because as a collector that’s the first stop. People go to Artsy or Artnet if they’re looking for transparency and pricing; they’re also looking for validation of who you are as a business. And if you’re not on there, then you don’t exist. It’s not even just about sales—it’s a marketing tool.

Are you putting works on Artsy?

Yes. We have sold quite a few works on Artsy but, as a small business, with the amount of money that it costs, we can’t afford the higher subscription plans that the mega-galleries can pay. They purchase banner ads and placement on the front page for collections that they may be featuring, because they are considered a VIP client. And the monthly price for us to be on Artsy went up considerably. Going to a website or Instagram page is not enough.

There is also the problem of the big auction houses having in-house advisors.

That’s a huge problem. Also a conflict of interest because the auction houses know the material that’s available, and they’re able to direct it to their clients in advance of putting it out potentially for auction. But they also know where artworks have sold. If they have a collector who is looking for specific artists or artworks, they can go back into their auction records to see who purchased that work previously and if they’d be

interested in reselling it in the secondary market.In some ways, the big houses are interfering with their own auctions by diverting works to secondary market sales.

I think it’s a conflict of interest. I will reach out to three or four auction houses to get estimates. But their terms for the auctions are different. If I introduce a collection to an auction house, the house may pay me an introductory commission, a fee based upon the sales. I’m very transparent with my collectors that I’m not going to take that introductory commission if I’m charging a percentage to my collector for the sale of the work. Then there’s the opportunity for auction houses as well as the mega-galleries to start manipulating the marketplace for certain artists and artworks. Because they can determine what the current fair market value is. You have to be knowledgeable in following the auction records and be able to access that information which is available at a premium price.

So how do you get around that?

That’s a hard one. You’ve got to do your research. For us, we have to pay it back into a subscription basis to be able to access the auction information and historical data, backtracking anywhere from 10 years plus, to be able to establish a foundation.

So that’s a service that they offer?

You can obtain some basic information for free, but a lot is subscription-based. They know that data is valuable and that they can charge for it.

It seems to me that if you go to any of the big three houses with a desirable painting, they could just decide to do a secondary market sale, right?

They have an advisory arm, and they have collectors who are looking for specific artworks. They may offer to try to sell it for you in the secondary market at a certain price point versus putting it on auction. Either way, the auction house is going to make money. And if they’re going to put a piece up for auction, they can charge you a seller’s fee, a cataloging fee and a fee for photography, plus they’re going to make the buyer’s premium. So, they’re skinning the cat on two sides. As an advisor, if you’re putting a work up for auction, you have to negotiate all those terms in advance every single time you talk to the auction house

-

From the Editor

May/June Volume 18, issue 5 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,In the early Artillery days, I assigned a writer to critique the films and videos that were showing in the sprawling 2007 MOCA exhibition, “WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution.” There were more than 20 films and videos included, mostly viewed on the original, portable black-and-white television sets or small analog monitors with bulky VHS recorders and other archaic equipment. Thick black cords, oversized headphones and extraneous hardware gadgets were in full view, making them part of the dated presentations.

After seeing the massively impressive, exhaustive exhibition (full disclosure: I pretty much skipped over the videos), it dawned on me that I should return and really watch the videos, all of them, in their entirety. The low-budget (or nearly no-budget) production of most of the work provided a window into the then newly discovered medium being used in art—video.

Besides my desire to go back, I thought that others might feel the same way. (Don’t most museumgoers skip watching the entire films at big exhibition shows?) I found myself drawn to the crude videos with the grainy black-and-white closeups of women’s faces and naked body parts—usually the artists themselves—always full-frame. Contemplative observations, confessions, questions, concerns and self-absorption seemed to be a running theme in a lot of the films. But really, could I sit through all of them? Perhaps I should’ve included a rating system when giving the writer his assignment to cover the show.

There doesn’t seem to be much need for help in making those decisions these days. In this Film, Animation & Video issue, we feature six female artists that make it impossible to walk away from their moving image pieces. For one thing, it’s usually the main thing in the exhibition, filling the gallery entirely, not tucked away in a darkened side room. Technology has leaped into a big fast-forward since the days of the “WACK!” show. Although Palestinian artists Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme draw on the past for inspiration, their multichannel, multisensory films look very different from the days of the portable black-and-white TVs. But they still talk about the things that are important to them, whether personal, familial, political or emotional, as reported by writer Tara Anne Dalbow. Admittedly, there are new matters to explore 20 years later. For instance, multidisciplinary artist Ethel Lilienfeld delves into 21st-century concerns, such as “self-image and the filters that augment—or completely change—our appearances,” writes New York contributor Annabel Keenan. Lilienfeld explores our virtual selves, or rather how we present ourselves in the virtual world. Women especially fall victim to the superficiality of social media, even to the point of going to plastic surgeons with their “filtered” double as a model.

In the end, the writer finally turned in his copy on the “WACK!” show, claiming he did as well as one could in the three hours he spent watching the videos and films. He came up with a rating system, and one of the films he watched in its entirety—and claimed to have been “mesmerized” by—was 27 minutes long. Our contemporary tools make the art of creating moving images a much easier process. But the message remains the same, as you will see in these pages.

-

SHOPTALK: LA ART NEWS

Frieze LA, Spring/Break, Gana Art LA’s Quiet OpeningI don’t know about you, but I’m still recovering from Frieze LA (Feb. 29–March 3), and the art week that was. In addition to the main event, there were many gallery openings and events, and also the Felix and Spring/ Break art fairs. At Frieze there were fewer galleries this year—about 95 versus last year’s 120—all packed into one big custom-built tent at Santa Monica Airport. Last year, most of the galleries were in the big tent, with a selection down the hill at Barker Hangar. Ironically, last year I heard complaints from gallerists relegated to the latter location, but Anthony Meier told me this year, “We did quite well after all, so we were happy.”

After attending the Thursday preview, I returned Saturday afternoon for some people-watching. Art fairs have become part of weekend entertainment, and Frieze drew an enthusiastic crowd, despite its high-priced admission. The aisles were jammed with friends on the hunt for new artists, young parents with toddlers in strollers and couples on dates. Kudos to the galleries that had one-person and thematic exhibitions; they really stuck in my mind.

Let’s take The Pit, with its walls painted in pleasing pastels, the back one dotted with white squiggles and shapes, which were ceramic pieces by Allison Schulnik that tell of the faceoff between two creatures outside her desert home, south of Joshua Tree. For an hour she watched as a snake and a cottontail rabbit confronted one another. “At first I was afraid for the bunny. I thought he’d be killed,” she told me. “Then I realized that the rabbit was the aggressor, sometimes moving in to nip at the snake.” The snake lunged forward, which made the rabbit jump and run away. This

drama was depicted in several pieces on the wall: the snake lurching forward, the rabbit falling back into a curl. “Fortunately, they both came out alive,” Schulnik reported.Los Angeles–based Gary Tyler won the 2024 Frieze Los Angeles Impact Prize, an honor saluting an artist who has “made a significant impact on society with their work.” He had a solo project at Frieze LA and received a $25,000 award. Tyler learned quilting during his 42-year incarceration, and he has used the medium to tell stories about his time in prison and the people he met. With quilting, he has said, “I had found my calling.”

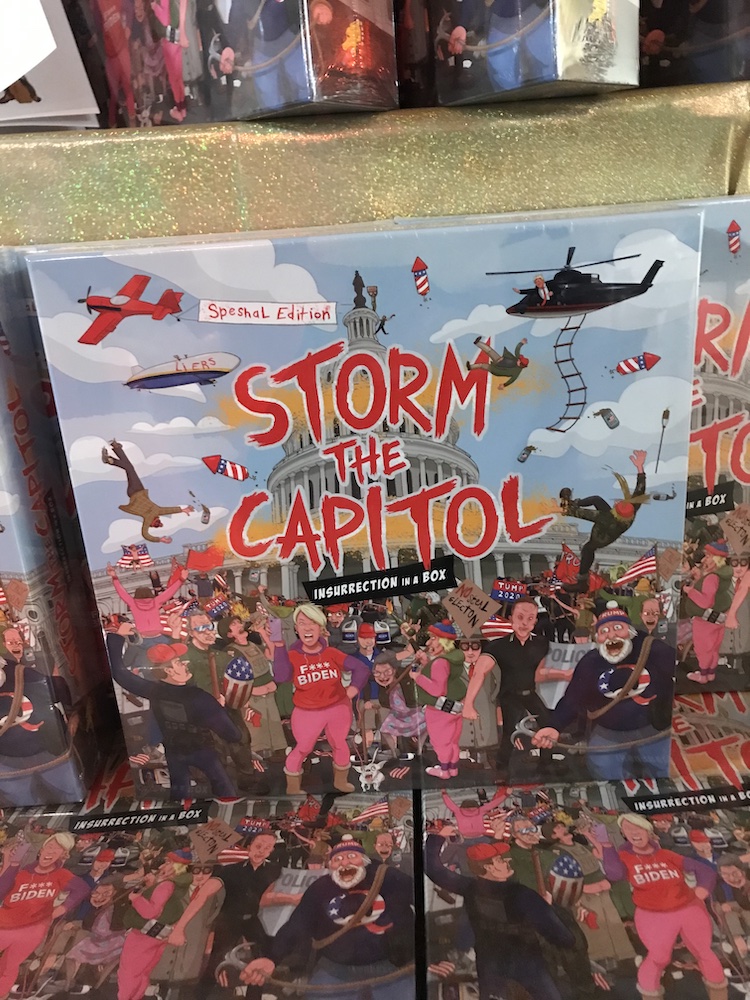

Board game Storm the Capital by Z Behl + Walker Behl + Tavet Gillson at Spring/Break. Photo by Ezrha Jean Black. For a break, I went to Spring/Break in Culver City—and found it refreshingly creative and friendly. Spring/Break has entered its fifth year in Los Angeles with some 90 exhibitors. Twelve years ago, Ambre Kelly and Andrew Gori launched the fair in New York as a fun alternative to the mainstream art-fair scene. They drew independent curators, artists without major gallery representation, or a combination of both. In Los Angeles this year, at least one stand was organized by two artists—Alonsa Guevara and James Razko, who curated each other’s work.

When Kelly and Gori started the Los Angeles fair, they were downtown. However, they always wanted to be arranged and geographically close to Frieze, which moved from Hollywood to Beverly Hills to Santa Monica. So Culver City seemed to be a good location this time, especially, as Gori points out, with an arts district nearby.

Inside the red brick building the fair occupied, there were walls dividing exhibitors, but hardly a plain vanilla cube was to be found. “We discourage white walls unless there’s a purpose for it,” Gori said. “These spaces come with their own character.” The exhibitors try to exhibit some personality, as well. They paint their walls different colors or give them a special treatment. They provide comfortable seating and linger in the aisles to chat and invite visitors in. Claire Foussard gave her walls a cement coating, and Yiwei Gallery painted trompe l’oeil Doric columns to frame its space. Others created installations—Z Behl + Walker Behl + Tavet Gillson built an immersive, 3D version of their board game, Storm the Capitol: THE “BIG” EDITION, a darkly comic look at the insurrection on January 6 in Washington, DC. Meanwhile, Hicham Oudghiri set up a tent that people could enter and sit in.

Foussard also featured two very intriguing artists. Angelica Yudasto created ethereal drawings floating in layers of kiln-formed glass, while Jiwon Rhie made a slapping machine mounted on an outside wall—a kinetic sculpture of a padded hand that swings around to smack you in the face. It was her way of venting the rejection she felt from various institutions after moving to the United States. At one point, Rhie bent over to demonstrate, putting her cheek in line with the hand. She smiled when I look concerned, and assured me, “It’s very gentle.”

Installation by Chiharu Shiota. On Seward just north of Santa Monica Boulevard is a new gallery that quietly opened last year—new to us, but the first American branch of one of Korea’s leading galleries, Gana Art. They opened an exhibition of work by Japanese artist Chiharu Shiota the weekend before Frieze, titled “In Circles.” Last year Shiota created that sensational installation using interconnected red string which engulfed the lobby of the Hammer Museum, one of the best transformations of that space. It felt like the inside of a magical spider’s lair. The gallery is housed in two small buildings, one featuring Shiota’s smaller works in display cases and on panel, the other a room-sized version of her installation work, based on three gigantic hoops. It was a wonder to walk throughout the exhibition.

The artist is now based in Berlin, but she paid a visit for the opening of her Gana exhibition in LA. In person, Shiota is quite modest and soft-spoken. She told me that as a child in Japan, she had seen the works of Dalí in the Sunday newspaper, and then became interested in art. She began drawing all the time: “It’s like my secret world, my own world.” To this day her art feels like a secret world: one we feel privileged to visit.

-

DYSTOPIAN FILTERS

Ethel Lilienfeld Considers the Nuances of our Virtual SelvesTechnology cannot be separated from the world we live in today. Indeed, post-pandemic, we are experiencing even more of our daily lives virtually. This phenomenon lies at the core of French multidisciplinary artist Ethel Lilienfeld’s work. Using video, installation and photography, Lilienfeld examines our relationships with technology and the virtual body—avatars we create to engage in digital realms. In recent years, she has considered self-image and the filters that augment—or completely change—our appearances.

“I am interested in exploring the codes of representing femininity throughout art history and examining how these codes have evolved in today’s digital age, especially on social media,” Lilienfeld, who was born in 1995, said in an email interview. “The relationship we have with our own

image has changed and is now continuously archived and updated online.”As technology advances, social media has become a tool through which humans grapple with the self and the truth behind what we view and consume online. We are now capable of creating virtual bodies regardless of whether or not they reflect reality. “This way of perceiving ourselves, especially through filters, has given rise to new neuroses, such as Snapchat Dysmorphia, a pathology characterized by the compulsive desire to resemble one’s digitally filtered self,” she explained. “It leads some people to go to the surgeon with their ‘filtered’ double as a model.”

This past March, Lilienfeld presented her work for the first time in the US in the 2024 FotoFest Biennial, the storied Houston photography exhibition. The artist’s four-channel video installation INVISIBLE FILTER (2022), was a standout of the biennial, which centered on “Critical Geography” and considered the broader ways and spaces in which we live and engage with the world today. Lilienfeld’s presentation is accessible and impactful: Featuring two identical women of markedly different ages, the work highlights the tension between fiction and reality, as well as the norms and biases perpetuated through social media, particularly those of age and beauty.

EMI, 2023. Production: Le Fresnoy–Studio national des arts contemporains. Co-Production: La Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles. Courtesy of the artist. On one of the four screens in INVISIBLE FILTER, the two women appear in a sparse room. They move slowly in an unsettling way, pausing and kneeling next to a large basin. The younger woman cries into the tub and the older woman bathes her own face in the tears. A digital beep sounds as the tears hit the surface, joined by choppy gasps for air. On another screen, the older woman looks into the camera, her face covered by a youthful digital filter that smooths her skin, a stark contrast to her heavily wrinkled neck. A third screen shows a reflection of what appears to be the older woman in the basin of tears, recalling Narcissus becoming enamored with his own image. “It could also evoke the story of Dorian Gray,” Lilienfeld explained. Closer inspection reveals it is the reflection of the younger woman, who is presumably aging as her tears drain her of youth. On the final screen, which is on the back of the third, forcing the visitor to move around the installation to reveal the story, the viewer watches from outside the house and sees that the tear-filled basin acts as a youthful elixir for the older woman.

In creating this work, Lilienfeld was inspired by social-media personalities and influencer culture, including the popular Chinese vlogger, “Your Highness Qiao Biluo.” During a 2019 livestream, a glitch revealed that the youthful Qiao Biluo was in fact an older woman wearing a filter. She was

suspended from the streaming platform Douyu and the story of her downfall went viral, a “contemporary fable,” as Lilienfeld called it. The incident sparked conversations about the ethics of filters, beauty standards and if online personalities owe their audiences the truth about their identities.

“INVISIBLE FILTER,” 2022. Production: Le Fresnoy–Studio national des arts contemporains. Courtesy of the artist. For her most recent project, EMI (2023), Lilienfeld addresses these themes directly. An interdisciplinary piece, EMI (an acronym for the French term for near-death experience) includes a film, website and NFTs. The project features a virtual influencer engaged in a frenetic advertisement-tutorial hybrid.

“Virtual influencers created from scratch have a story to tell, sharing their tastes, passions and vision with their community through a transmedia narrative,” Lilienfeld said. “They promise to stay eternally young and fashionable, and never have reputation problems.”

Produced with Le Fresnoy—Studio national des arts contemporains and co-produced with La Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles, the project combines artificial intelligence, real footage and computer-generated images, demonstrating how advances in technology blur reality and fiction. The influencer overindulges on opulent food, drinks off-putting health supplements and uses beauty tools that pull on her skin, revealing glitchy eyes. “Behind its seductive form, EMI explores the increasing capitalization of the body online, inviting us somewhere on the edge of the beautiful and the repulsive, the real and the fictitious, the living and the dead,” Lilienfeld said.

For the NFT component, collectors become stewards of the influencer’s organs, a metaphor for the sense of ownership that people have about public figures and online personas. The organs come with a description similar to that of an autopsy report. As twisted as this might seem, it’s not unlike wearing another face through a digital filter—an act we’ve normalized on social media. Indeed, while Lilienfeld’s work is intentionally dystopian, it’s hard not to wonder if it’s that far removed from reality after all.

-

SHATTERED

Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme Find Meaning in Remembrance and ResistanceIn the 18th century, when the Iranian elite heard rumors of the grand mirrored halls of Europe, they sent merchants to procure as many sheets of brilliant reflective glass as their boats could carry. Still, the mirrors cracked in their elaborate frames somewhere between Venice and Tehran. Rather than attempt to reassemble the shattered glass, artisans inlaid the thousands of pieces in sweeping geometrical patterns along walls and across ceilings. The mesmerizing designs accentuated these tesserae pieces but also distorted the surface reflection, fragmenting the viewer’s image and intermixing it with that of peripheral objects and other people.

Palestinian artists Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme create similarly revelatory mosaics not from glass but from pieces of archival footage, original documentary imagery, soundscapes and text. Their multisensory installations mirror the dispossession of diasporic communities, evoking fracture on a visceral level.

Abbas and Abou-Rahme first met in 2007 when their respective performance-based practices converged: Abbas’ DJing and Abou-Rahme’s work in video design. More than a decade later, performance remains at the heart of their ongoing collaborative practice. Through their nondiegetic sound collages and multiscreen projections, they position performance as political action in which collective movement engenders resistance and resilience. According to the collaborative duo, collective sound and movement rituals—including song, poetry, dance and gesture—afford displaced communities a critical means for resisting their own erasure while reclaiming a sense of self and fraternity.

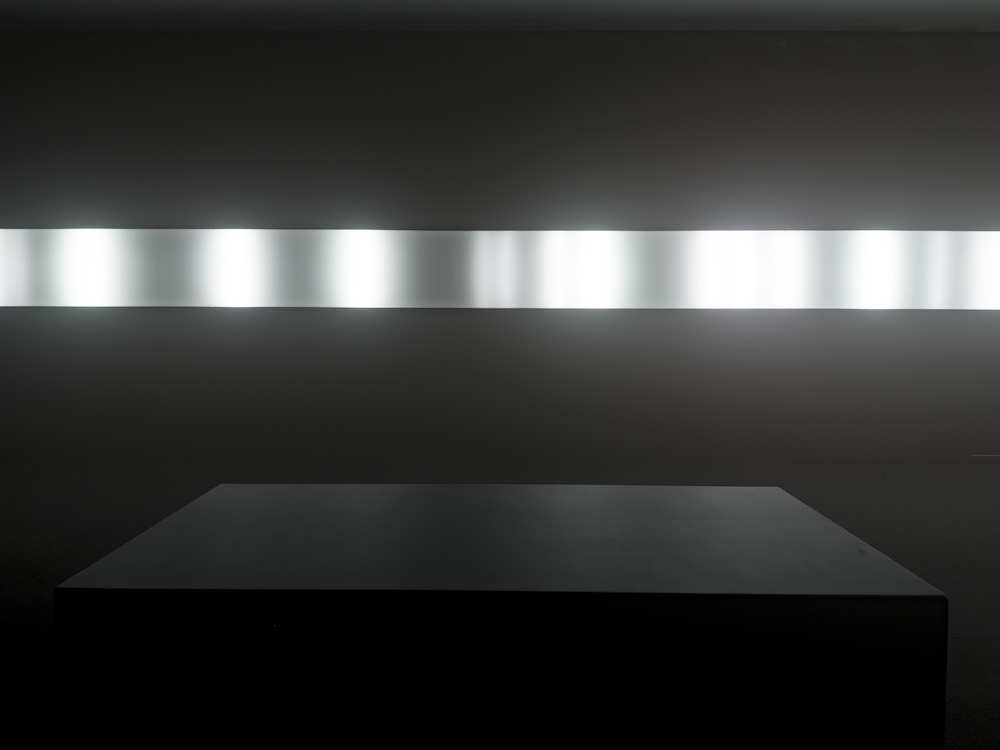

Installation view of May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth: only sounds that tremble through us, 2022, Basel Abbas / Ruanne Abou-Rahme. An echo buried deep deep down but calling still. © Astrup Fearnley Museet, 2023. Photo: Christian Øen Their immersive installations are poised at the intersection of body, affect and space, negotiating between physical, digital and virtual realms. A three-channel video projected onto overlapping screens project film clips, graphic animation and excerpts of text by the artists and other authors. At the same time, enormous speakers produce pounding bass lines and rhythmic chanting. A phantasmagoria of moving images breaks apart, flashes, descends and dissipates across a collage of small and large rectangular screens, producing a disjointed viewing experience not unlike that of looking into a tessellated mirror.

In their decade-long project, May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth (2010–ongoing), Abbas and Abou-Rahme intermingle original footage with video clips sourced from online archives and social media posts of people singing and dancing in Palestine, Yemen, Iraq and Syria. Using a handheld camera, they record people’s improvised interactions with the land, preserving the real-time unfolding of a moment that, in their words, “can activate something that was otherwise inactive,” and gesture to the invisible just beneath the material surface. By merging archival and original film, the artists forge connections across time and geographical locations and visualize the legacy of resistance in a way that allows the past to instruct and inspire the present.

“We are engaged in producing a nonlinear reading of ‘our’ time that allows for a sense of multiplicity both conceptually and formally,” say the artists. To that end, their projects are formally malleable, continuous, “unbounded” and capable of accommodating shifting responses to ongoing events.

Installation view of May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth, 2022. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Digital Image © 2022 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo by Jonathan Muzikar. For example, their most recent work, Only sounds that tremble through us (2020–22), first shown at the Museum of Modern Art in 2022 and now open at MIT List Visual Arts Center, revisits the material and conceptual concerns animated by May amnesia. In collaboration with Palestine-based performers—dancer Rima Baransi, electronic musicians Haykal, Julmud and Makimakkuk—Abbas and Abou-Rahme filmed their respective performative responses to the original archival footage of people dancing and singing at weddings, funerals, political demonstrations and impromptu social gatherings. These fresh improvisations both echo and evolve the inherited gestures, lyrics and rhythms. The looping voices and images increase in urgency, capturing the perpetual dream of Palestinians in the diaspora to finally return to “the lost ground of our origin, the broken link with our land and past,” in the words of Palestinian-American literary critic Edward Said.

Juxtaposition, symmetry and abstraction precipitate resonant connections between the seen and unseen, the spoken and the unspoken, without imposing any artificial structural unity onto the flux of images and texts. Complex layers of rhythm and repetition celebrate the generative possibilities of mutability, simulating how someone, in becoming other, can become more fully themselves. In this way the installation unites the degradation and violence of colonial conditions with the exaltation of collective endurance and ingenuity in Möbius strip continuity.

Through montage, the artists accommodate the complexity and multiplicity of experience—and the stories we tell about experiences—while pointing toward radical new formulations of identity and culture that disregard geopolitical boundaries. Just as the shattered glass recast perception, intermingling the self and other, Abbas and Abou-Rahme’s segments and soundbites envisage the possibility of “transcending the material constraints of individuality to see ourselves reflected in the glittering constellation of everyone else.”

-

AS THE WORLD TURNS

Deborah Stratman Gazes Into the Abyss of Time“I’m not sure satisfaction is a thing I feel while making art. I get satisfied from stuff like getting my laundry done or digging a trench or putting away my books,” mused director Deborah Stratman in a recent interview with Documentary magazine. Perhaps this questing, open-ended relationship to her practice is why, at age 57, Stratman has nearly two dozen films to her name. An associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago, where she’s based, Stratman has exhibited work as far and wide as the Whitney Biennial, MoMA, Centre Pompidou, Hammer Museum, ICA London and pretty much every international film festival circuit. By some accounts, her video assemblages are the first to be described as “experimental documentary.”

Typically, Stratman directs, shoots, edits and designs the sounds for all her films, which eschew narrative conventions of causality or linearity in favor of the associative logic of a collagist. The gestation period for each production is unpredictable, sometimes lasting months, sometimes years, although “there’s a tipping point where if I were to keep collecting, a film loses momentum and I get bored,” as Stratman explained in a conversation about Last Things (2023), her latest documentary. “For essayistic films like this one, I accrue way more material than I can use. Then I condense that unruly, amorphous cloud to try to say as much as I can in as few moves as possible.”

The opening shot of Last Things is the earliest known rendering of the Milky Way, a drawing by astronomer William Herschel from 1785. It resembles an approaching figure, with our sun where the heart would be. “All the world began with a yes,” quotes the clear, softly accented voice of filmmaker Valérie Massadian, one of two that will echo in voiceover throughout Stratman’s “science factual” film. “One molecule said yes to another molecule and life was born,” Massadian continues, “but before prehistory there was the prehistory of prehistory.” This epoch is the focus of Last Things. A mesmerizing collage of video, images and quotation—this first line is from Clarice Lispector’s 1977 novel The Hour of the Star—Last Things radically decenters mammalian development from our narrative of the planet’s becoming. This is evolution from the geological perspective: 16-millimeter footage of wildly spiraling, propagating crystals, glowing stalactite caves, microbiological family trees and other ephemera from the mineral world conjure a fruitful planet in which humankind is a peripheral organization of matter.

Still from The Illinois Parables, 2016. Some scientists have called the Anthropocene “the geologic turn,” since the planet is experiencing change on a scale not known in human history. Last Things, likewise, faces backwards and forwards, describing both the past and the possible post-human future. Stratman fuses together two stories by the 19th-century speculative fiction novelist J.-H. Rosny to form a narrative voiced by Massadian, in which inorganic alien life forms—the geometric Xipéhuz and the crystalline, iron-eating Ferromagnetics—have colonized Earth, laying waste to human society and leaving only a few unlucky survivors to bear witness to the new geological order.

The other voiceover in Last Things comes from geologist Dr. Marcia Bjornerud, partially from interviews recorded with Stratman, and partially from lectures given for a course known as HELL (the “History of Earth and Life”) at Lawrence University in Wisconsin. Acting as an ambassador from the geo-biosphere, Bjornerud advocates for a “poly-temporal” worldview that incorporates the overlapping rates of change that effect our planet, particularly those that are so powerful they mostly surpass the scale of human perception. Rocks, too, can adapt, evolve and go extinct, she explains; but their lifetimes are beyond anthropocentric comprehension.

Still from Last Things, 2023. The enormity of planetary timescales, which render almost any form of life fleeting, carry a kind of inherent violence. For her part, Stratman has said that “low-grade terminal anxiety” about being in the midst of the sixth great extinction was the catalyst for making Last Things, which has been slowly migrating to independent theaters across the United States. Her filmography often contextualizes human activity within a topographical scope—in such films as O’er the Land (2009) and The Illinois Parables (2016), Stratman foregrounds the landscape as constructed by various ideologies but ultimately resistant to it; no matter how territory is divided or appropriated, human struggles play out upon an unfeeling terrain. Nobody talks about global warming in Last Things, but they don’t have to—extinction proves cyclical, change once again the rule.

I was able to catch a late-night screening of Last Things at a local theater on a special limited run. Afterwards, stepping into the night air outside the theater, I had the profound sense that I was just visiting. It’s a relief to leave behind the messy, fleshy human world for something more perfect and enduring.

-

REALM OF THE SENSES

Jónsi’s “VOX” at Tanya Bonakdar GalleryJónsi, artist and frontman of Icelandic post-rock band Sigur Rós, masterfully crafted a recent show titled “Vox” which challenges the definitions of visual, sonic and olfactory art, merging the mediums to form a multi-sensory exhibition that plays on the viewer’s mind and body.

The entry point to the show is Var (safespace) (2023), a tapestry of hundreds of micro speakers draped over a rope strung diagonally from one corner of the room to the other. Reminiscent of a rudimentary tent, the speakers emanate a mixture of bubbling water, faint whistling, ambient techno and other sounds that swirl together in a surprisingly gentle cacophony. The intensity of noise shifts as you walk around and under the sculpture, creating new sensations with every pass, all accompanied by a faint smell of cis-3-Hexen-1-ol, the semiochemical associated with the scent of freshly cut grass. Closing your eyes, the soothing and often nostalgia-inducing aroma intertwines with the sounds to transport you to a

tranquil space of your choosing.In a separate enclave of the gallery is Silent sigh (dark) (2023), a large sculpture, the face of which is a circle made of 100 different-sized speakers arranged with the largest in the middle and the smallest on the fringes, like some organism growing outward. A deep, metallic arpeggio-like sound filters out of them, and with each beat the speakers softly pulsate—pushing the noise from the sculpture’s center to its edges and back again, like a rock skipping on water or a heartbeat. Each note becomes physical as the speakers hammer forward with every beat. The subtle throbbing creates a visual ripple that carries your eye through the sound.

Jónsi, Vox, 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles. Combining the multitude of senses of the two sculptures, the immersive installation shines as the focal point of the exhibition experience. Behind a heavy black curtain, the darkened room is illuminated by four LED screens that run the length of each wall. In the center is a bench, with speakers underneath that vibrate through the body of anyone who sits on them. A deafening combination of Jónsi’s voice and AI-generated vocals resound throughout the room, passing beyond intelligibility as they mix in a dissonant yet beautiful sound. Fog-like air embraces you as vetiver and other earthy notes are vaporized into the room. The multisensory work builds on the basest interpretation of video art as light displays morph across the screens in response to Jónsi’s voice. In the thick atmosphere, the installation is all enveloping, with each breath contributing to the work. This deeply corporeal but highly ethereal show—even with your eyes open—is almost a holy experience.

-

LOST IN SPACE

The New Restoration of Franco Rossi’s “Smog”Franco Rossi’s restored Smog plays like a Nouvelle Vague travelogue, with protagonists seemingly lost in an urban landscape that amplifies their inner malaise. That backdrop is Los Angeles and the long-lost 1962 film (now finally available in a pristine 4K restoration by Cineteca di Bologna and UCLA Film & Television Archives) is also a snapshot of the city in its modernist “adolescence.” At the time Rossi was one of the very first European directors to film entirely on location in the US, and director of photography Ted McCord (East of Eden (1955), The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948)) captured the sprawl in stark black and white, including lost Hollywood landmarks, Pierre Koenig’s iconic Stahl House (Case Study House #22), the Baldwin Hills oil fields and (at the time) a just remodeled LAX. Vittorio, a Roman lawyer, played by Enrico Maria Salerno, is forced to spend 48 hours in the city due to a missed flight connection. Confounded by the undecipherable geography and its rootless inhabitants, he is both attracted and repulsed by what he considers the vapid lives of the Italian expatriates he encounters, including enigmatic Gabriella (Annie Girardot). The film uses the Los Angeles location to explore themes of mobility and impermanence, identity and displacement, a metaphorical gaze on the city, which was becoming a subject for artists such as Ed Ruscha, Joan Didion, Dennis Hopper, David Hockney and Charles Bukowski—as well as the locus for a veritable explosion of mid-century architecture. The movie, which also includes a haunting score by Piero Umiliani and Chet Baker, screened that same year at the Venice Film Festival before disappearing, unreleased, into the vaults from which it just now re-emerges as a singular time capsule

-

FIELD REPORT

Art For All: The Gilbert & George Centre, LondonGilbert & George, the quintessentially British pioneering queer artist-duo have staked a clear position within the milieu in which they operate. They have scant tolerance for art-world conventions, yet it is precisely that peevishness and their enduring, long-term collaboration that created the context for the creation of their provocatively lurid and iconic works.

On a recent trip to London, I made my way to their fairly new public art center—situated in the once dodgy Spitalfields district of East London. Gentrification has since transformed the area into a fashionable yet unpretentious neighborhood. The entrance to the Centre, approached from a quiet lane, is gloriously framed by an extravagant green wrought-iron gate distinguished by a rococo G&G flourish. Opened in 2023, the museum holds three gallery spaces in a renovated 19th-century brewery building.

Important figures in British Conceptual art, these two self-proclaimed monarchists—Gilbert Prousch, born in Italy, and British-born George Passmore—are now in their 80s. They are renowned for their nearly identical modes of dress—usually matching suits, which serve as a kind of domestic performance art and mediating foil for reactions to some of their more outré artworks, which often include self-portraiture. They have been constant partners since meeting at Saint Martin’s School of Art in the 1960s—a ferocious and storied alliance that resulted in, as Passmore quipped, “Two people, one artist.” Early formative works included The Singing Sculpture (1969–91), in which the pair painted themselves bronze and sang local public dirges—garnering much attention as a result—and Coming, 1975 (1975), a controversial suite of nine black-and-white photographs depicting ejaculation. In the 1990s, their works took on an increasingly scatological bent, with palettes of hallucinogenic intensity.

©The Gilbert & George Centre (UK) Ltd. Photos by Prudence Cuming. In some ways the Centre seems like an attempt to hedge their bets—to create a permanent edifice devoted solely to their output. It was always envisioned as a free public venue, in line with their “Art for All” philosophy. Rather than overwhelm the visitor with architectural excess, the brick-enveloped ambiance embraces one with a cocoon-like sensation; the building and its inner courtyard are quietly elegant and tranquil.

One small inner gallery contains prints—white with black lettering—and waggishly irreverent slogans such as “KISS ME,” “FUCK ’EM ALL” and “I’M STRAIGHT.” The larger light-filled galleries are achingly serene, an exercise in unobtrusive, graceful details. On view at the time, “THE PARADISICAL PICTURES” was a visual heaven-on-earth whiplash: a selection of 20-plus manipulated pictures with eye-punching colors. At a distance, the overarching sensation was of quasi-sacred imagery and ersatz stained glass. But closer inspection revealed collages of floating eyes and such detritus as leaves, rotting fruit, flowers and, of course, the artist themselves. Rest (2019) depicts the pair reclining on benches backgrounded by a wildly colorful bed of live and decaying flowers, resulting in a mordantly romantic tableau. This visual insurgence sits in stark contrast to the beautifully restored edifice—perhaps that’s the point.

Gilbert & George are, ultimately, iconoclasts—unconcerned with art-establishment machinations and critique. They are now free to curate their own Centre unfettered and redefine what it means to be a subversive artist in the 21st century.

-

POEMS

“Chalk Poem” and “The Lugubrious Game”Chalk Poem

The long cool freedom

pure as a stick of chalk

powdering against the

edge of jealousy

hard and green, also cool

a tongue in your mouth

an equation in your mind

about where

purity goes

as it’s clapped against

a tree trunk,

the side of a building

leaving squares of dust,

only its traces.—Caitlin Brady

The Lugubrious Game

Do you ever look at the work of your friends

purely in order to marvel

at its shortcomings: to spitefully wallow,

with sheer horror and disbelief,

in its shockingly abysmal incompetence,

and cheerfully reassure yourself

of its utterly irredeemable worthlessness?

If not, you are missing out

on one of life’s greatest pleasures.

So much more pleasurable than

looking at a friend’s work and finding

that it surpasses anything

you could ever hope to achieve.—John Tottenham

-

BUNKER VISION

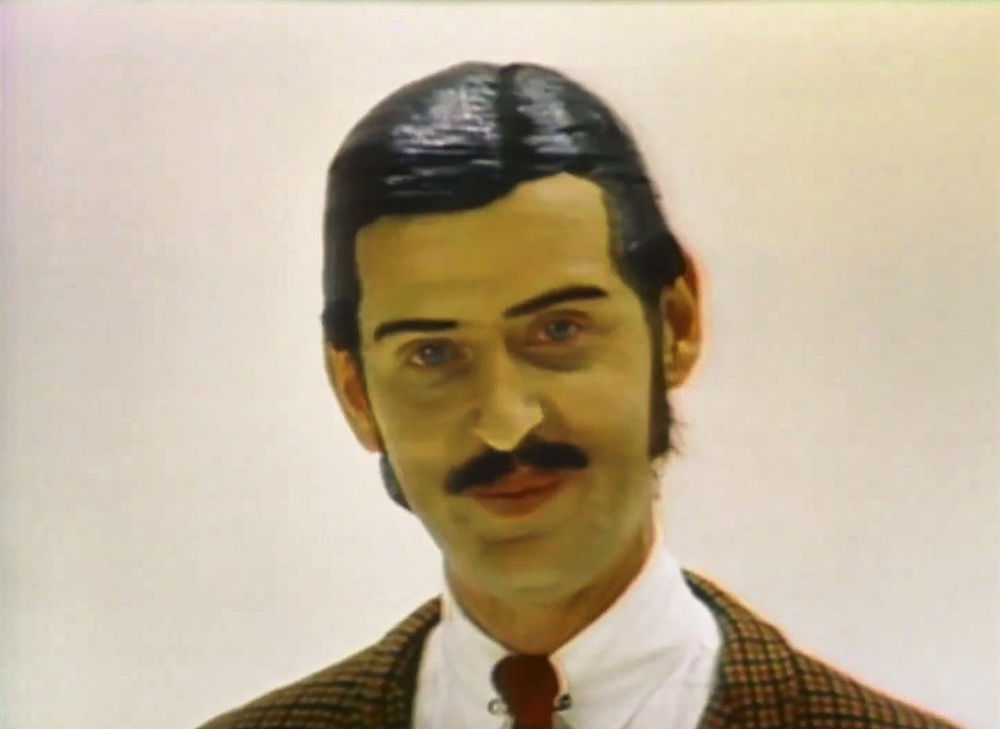

The Prime-Time Underground FilmThe history of film is full of paradigm shifts. Once people got used to the idea that the train on the screen wasn’t going to burst into the theater, they had to adjust to editing. When a character had a memory, the idea of linear time was disrupted. One of the biggest shifts arrived with the debut of MTV in 1981. Until it arrived, the most likely way one would have seen those rapid edits would have been in a film history class that was studying Russian cinema, or such underground works as Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1963–73). This might help one to understand how shocking a TV show called Turn-On was to the uninitiated viewer in 1969. A year earlier, a television show called Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In (1968) featured rapidly edited blackout comedy sketches. But these were offered in the context of a show that had tuxedo-clad hosts and Hollywood production values.

By contrast, Turn-On billed itself as the world’s first computerized show. This premise allowed them to dispense with sets, as the skits would appear with a white background with Moog synthesizer sounds instead of a laugh track. The show was shot on film (unusual for the time) and the screen would sometimes divide into four images. Animation, videotape, stop-action film, electronic distortion and computer graphics were employed for what was intended as an audio-visual assault. Going with the mistaken idea that Laugh-In had broken more ground than it had with censorship and fast-paced editing, the creators of Turn-On sought to push the boundaries even further. The edits became faster, more random, and were used to sneak in things that might get past the censors. In this pre-VCR era, such things were quite literally a blink, and you missed it. You couldn’t stop the picture or rewind what you had just seen.

Within minutes of the show starting to air its premiere episode on the East Coast, the switchboards were lit up at every station that aired it. Viewers weren’t just upset by the content; they were experiencing a form of sensory overload that nothing had prepared them for. Households where more than one set of eyes were on the screen were catching those hidden bits in the montages. Stations started pulling the show off the air during the first commercial break, and some stations further west were refusing to air it altogether. Despite having a second episode in the can, the show was canceled and thought lost. Recently, both episodes turned up on YouTube. It hasn’t aged especially well, but it’s wonderful to remember a world in which millions of primetime viewers got to see an underground film

-

ART BRIEF

The Role of an Art AdvisorWendy Posner is the CEO of Posner Fine Arts, an international art advisory based in Los Angeles. With a global roster of artists, publishers and gallerists, she builds relationships with both established art stars and new talent. She has traveled to more than 20 countries regularly

attending art fairs and making studio visits. I’ve known Wendy for 10 years, sometimes as a client of my legal practice. We discussed how the role of art advisor is facing the challenges of mega-galleries that have recently added in-house advisory services.Stephen Goldberg: What are the challenges of mega-galleries, such as Hauser & Wirth, expanding into the art advisory field?

Wendy Posner: Most of the large galleries have now added advisory arms to their business, outside of doing private sales, where they’re even looking for secondary market pieces for their clients, not just the primary works that gallery is selling.

As a fine art advisor, the main conflict of interest is that we would normally take our clients to the galleries to purchase artworks, and if they’re also now acting as advisors, they might take those clients from us because they have offerings that we don’t have access to—from their collectors that they work with, in addition to their primary works. If any collector walks into a mega-gallery, they’re going to be offered the same discount that’s offered to advisors, so that incentivizes the way that we would normally be paid. How do we pass off a discount to our collectors, when the percentage that the gallery is offering the collector is the same as what they’re offering to the advisor?

Mega-galleries have deep pockets. They’re able to go and market directly to the collectors, and they have more funds for staffing. In the traditional way of art advising, it wasn’t something that you charged your clients an hourly fee for; your time was paid for in the sale of the work. It’s become exponentially more difficult because unless a collector buys a piece of art, we don’t make any money.

If you’re competing with the mega-galleries who know which of their collectors own works by certain artists, they can always go back to their collector base and start selling their works into the secondary marketplace. Now the level of transparency has completely changed with more information online, and collectors at a certain level are much savvier. And charging for the services is really where the money is going to be made, not just in the sale of the markup.

Are there any examples of losing clients to a gallery?

I had a collector that was looking for a painting by a specific artist. We had worked for about six months to find works by that particular painter, and it ended up that the collector back-doored us and went to a gallery directly. The gallery gave them the same discount that we would have gotten as an advisory to make the sale. We were completely cut out of that deal. I think that’s part of the issue when you’re taking collectors to the art fairs and introducing them to the galleries, and you’ve curated artworks for them to see with specific galleries, that even if they don’t end up making the sale through you they could easily turn around at a later date and go directly to those galleries—unless the galleries protect you.

What about an agreement upfront that would permit you to be able to bill clients for your time?

That’s what a lot of advisors are starting to do, create this new business model. But with collectors that we’ve worked with for 30 years, if that isn’t a traditional methodology of which they’ve acquired artworks for, how do you re-educate them in terms of a new business model? So there’s definitely a shift in the marketplace. The other part of it is that the discounts we were able to get in the past were much steeper than the discounts that are now customary across the board. The galleries have a standard discount for commission. With other galleries that we have long-term relationships with, the discounts could be variable, and they could be much more than the standard. But if a known collector walked into that same gallery, they’re going to be offered the standard discount to make the sale. So you’re in competition with yourself and with your collectors for that discount rate. Unless it’s a mega piece, you’re making a nominal amount of money for the time that you’ve spent with the client to acquire that.

Are you giving collectors a written contract?

We put together agreements for our collectors that we’re working with, because we have to be able to protect ourselves. But with the mega-galleries there has to be some sort of relationship established upfront before we even take our collectors to those galleries.

Do you have a conversation with them?

Yes. You have to have some sort of terms of agreement with them and everything is negotiable. So it has become much more complex.

This is part one of a two-part series. In the next installment we will discuss online sites such as Artsy and the auction houses that have now expanded into the art advisory space.

-

THE DIGITAL

Tala Madani Explores the DarknessHave you ever howled at the moon? Stood up to your demons and screamed until your lungs ached? I have once. It was in the wee hours of the morning in Thailand. It was a pivotal moment in my story, and to scream without judgment was where I found solace, but that is a tale for another day.

Darkness exists both in this world and in the shadowy corners of our consciousness. How do we deal with that? Some confront our demons more naturally while others keep them under lock and key. This darkness is where our inner voice is not censored or muted—where our most extreme visions are exposed without judgment or humility. There is an old saying about strength and secrets: Strength doesn’t come from having ones secrets protected but rather from exposing them.

Enter Iran-born artist Tala Madani, who for decades has explored the visual space that would make others cringe. In the South-Park methodology, strong subject matter is dealt with in a backhanded and seemingly juvenile way. Madani saunters through the shadows with a childlike grace of style and sensibility, because in the end who doesn’t love a good scat joke?

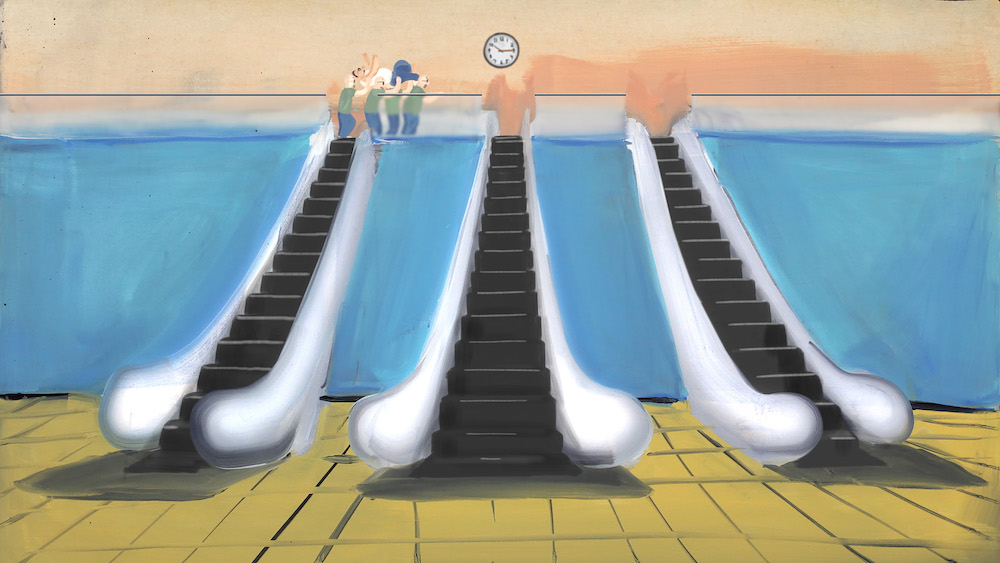

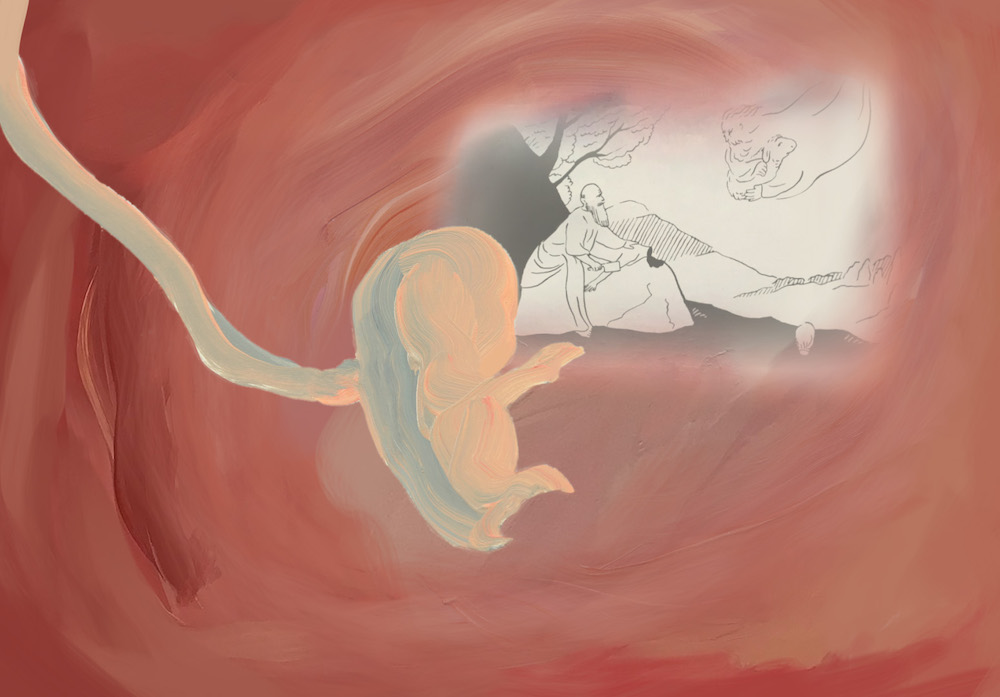

Still of The Womb, 2019, single-channel color animation, 3 min. 26 sec. Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery. Madani’s paintings—some of which provide the foundation for her animations—exist in large format, and as we talk about technology and the crossover into art, she jokingly says that her interface with technology typically exists at the most basic level, “taping a longer stick to a paintbrush so it can be extended, knowing when to switch from a paintbrush to a mop.” While there is a subtle layer of both humor and truth to her statement, I would argue that the veins of digital manipulation run more deeply as one explores her prolific body of work.

Madani’s animations are a testament to that depth—you lean into what you have and toss aside the rest. There is something viscerally exciting that happens in her animations, essentially stop-motion activations of her paintings that simply cannot be reproduced in a magic computer box. The fact that it can take 2000 paintings to make a two-minute video opens a portal in which her paintings step through, as if from the plot of B-grade horror movie. Painterly movements are accentuated, viewing angles change, and even if slightly—characters develop.

For example, in her early animation Hospital (2009), a male figure lies in a bed covered in bedding, with only his head revealed. Another figure enters the room, stands beside the bed, then walks out. Soon a diaper-clad baby crawls (in a beautifully creepy way that stop-animation allows) in from the adjacent patient’s room, separated by a curtain. The baby pulls its way up onto the bed and makes a thumping motion on the man’s chest that is suggestive of a worshipful gesture. The scene quickly changes from playful to dark as the baby’s hands, the entire bed and man’s head gradually transform to a blood-red pigment. The baby then crawls off of the bed and exits the scene, the video ending.

The rough flip-book style animation draws one in as it plays off the painting, and, inversely, the paintings play off the animations. As in much of Madani’s work, light and shadows are paramount to the visual scene—her digital connection provides the illumination to reveal all the perverse secrets hiding in the darkness.

-

PEER REVIEW

Olivia Mole on Fox MaxyLondon-born, Los Angeles–based video artist and animator Olivia Mole is known for her recurring characters in many of her works, seen in pieces presented at the Hammer as well as in her solo show at Gattopardo last year, “A Bear Shits in the Woods.” Always with a sense of humor, Mole’s work probes pop and consumer culture and verges on the absurd. Mole’s exhibition at Tiffany’s, organized by Adam Verdugo, opened in April and is titled “Dopesheet Batman”; based on an original animation dope sheet of the iconic moment of Daffy Duck stating, “I’m Batman,” Mole’s new body of work explores the gaps between aspiration, identity and presentations of self.

I saw Fox Maxy’s Gush play at the Hammer last year because my friend Vanessa Gonzalez Medina recommended it to me, so I went into it pretty cold. It’s intense and exhilarating to watch; superficially it’s like an extended sort of TikTok, like watching a cascade of short videos one after the other. Some scenes are more designed and constructed as opposed to the way that everyone uses their camera in their life. Maxy is Payómkawichum and Mesa Grande Band of Mission Indians, and she has made a lot of work about the colonization of Indian land within the USA and at the border of Mexico. The complexity in her work—it’s not as simple as the colonizer versus the colonized—exists in setting the vicissitudes of daily life within the diverse struggles of Native American people to protect their land, status and existence. It adds to its genius that she is working really solidly within a cultural landscape of video, cinema and social media while dealing with this grand subject matter of surviving as a part of a generation coming up in the terrifying narrative of global warming.

Still from Fox Maxy’s Gush, 2023. The thing that really clicked with me was the animations in the film—every so often the film goes into CG animation with floating innards of the body, very shiny guts, eyeballs and organs writhing around in space, little moments of blood. While I was watching the film, absorbing all of it, I realized it’s like a deconstructed horror film, fragmented and not put back together, in a constant state of flux. It defies Hollywood narrative structure. Furthermore, when accounts about the end of the world and the apocalypse arise in mainstream media, it’s as if the end is yet to come. But for Native American people and other colonized people, it has already come, and it’s like Gush is set within that. It seems to be so unstructured yet is tied to a cinematic genre that is usually very set with tropes and expectations. She messes with the foundation and then brings “real stories” into that with horror as a stealth genre. But it’s also so energetic and filled with vitality and humor. It doesn’t suggest a submission to what’s happening, to just have a good life with what we can. Nor is it defeatist in the face of catastrophe. It’s full of pain, joy and sadness, inhabiting this kind of state of horror with a fierce commitment to life. — As told to Alex Garner

-

ASK BABS

For the DogsDear Babs,

I graduated with an MFA in painting two years ago and while I have a decent record of solo and group shows under my belt, I don’t really make any money from sales of my work. I have a stable job as a bartender that pays the bills, and I’m all right building my practice slowly. My problem is that my parents are on my case about how I’m not getting a financial return from my degree, which they in part helped pay for. Recently my dad suggested I start painting portraits of their neighbors’ dogs because I’d be “putting my education to good use.” How do I get my parents to stop badgering me and let me be the artist I want to be?

—Misunderstood in MinneapolisDear Misunderstood: Congrats on your steadfast dedication to your artistic growth; we all know it’s not an easy path to follow. It’s hard for people outside the art world to understand the financially “counterproductive” choices some artists make in service of long-term career integrity. Conventional thinking would have you make money any way you can by painting any way you can, but that’s just not how to make an art career worthy of serious attention.

It’s time for you to sit your parents down and give them a little lesson in what an art practice actually means. They wouldn’t tell a young lawyer to stop practicing civil rights law because chasing ambulances is just easier and more profitable, would they?

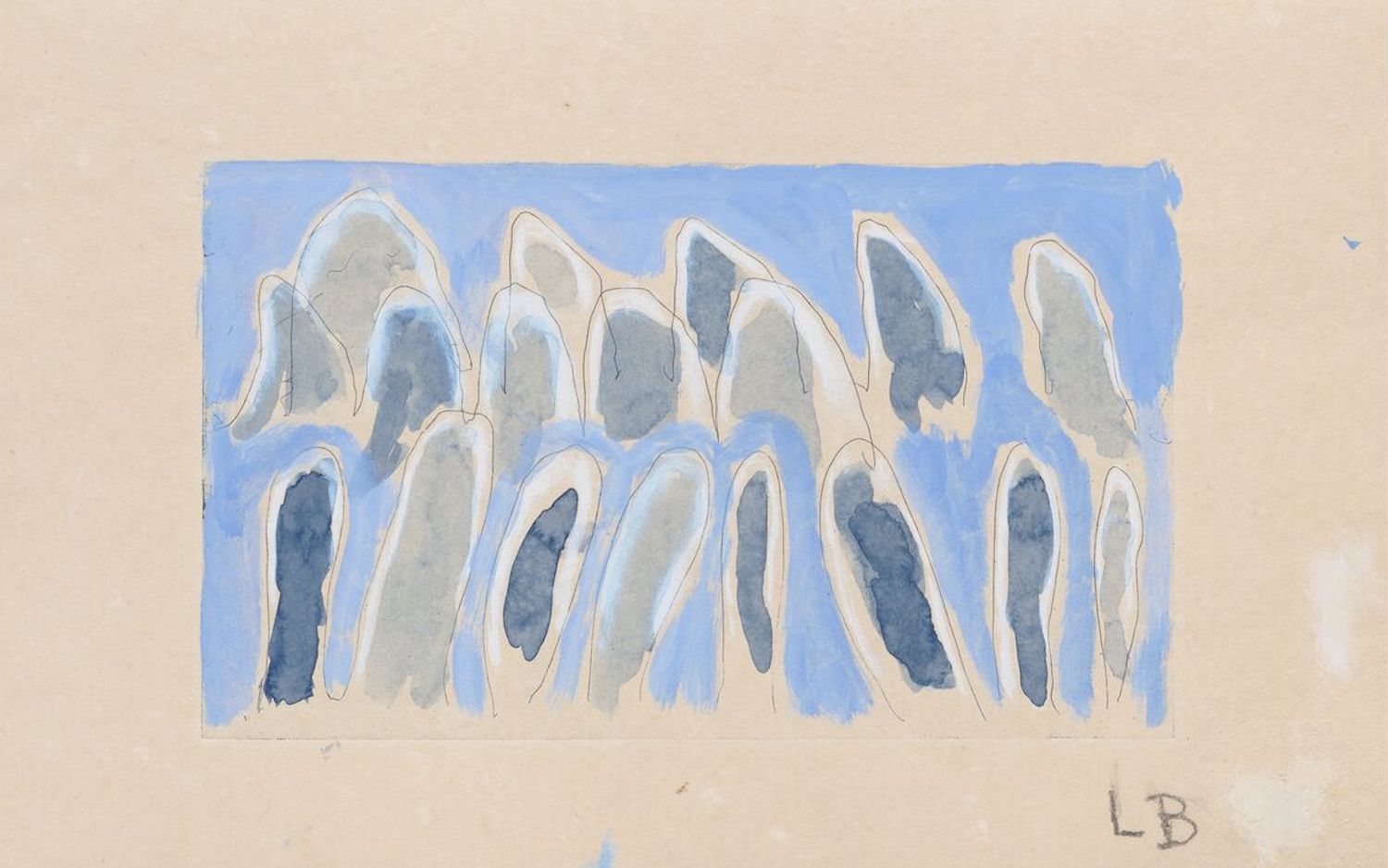

Suggest a family get-together where you watch a few Art21 episodes curated by you with a focus on artists who worked hard to maintain their integrity in the face of financial and familial pressures. Help them learn about how long it took Louise Bourgeois and John Baldessari to actually make a living off their work. Perhaps with a bit of education your parents might understand why it’s important for you to focus on the work you need to while not distracted by commissions for things that don’t further your long-term creative goals. Or you can always consider making some really messed-up pooch paintings of their neighbors’ pets. Who knows, it could be the start of a new, cathartic body of work.

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,