John Cage and Leah Ke Yi Zheng’s joint exhibition, “The Grasshopper Lies Heavy,” presents two aesthetically dissimilar bodies of work with overlapping concerns that entangle them. The I Ching, an ancient Chinese divination tool that uses hexagrams to predict divine will, is central for both artists and guides the form of their works. Through this connection, the pairing reflects exceptional affinities for and contrasting applications of the famous Chinese book.

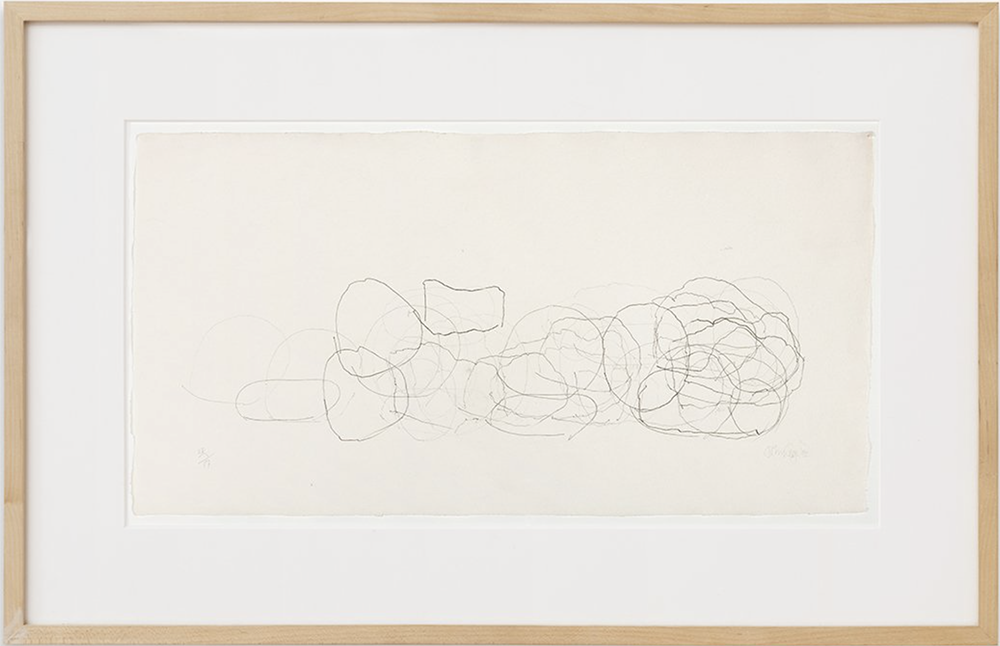

Cage’s visits to the Ryōan-ji Temple rock gardens near Kyoto inspired a group of sparse drawings. The five works displayed in the exhibition from this series are all 10 x 19 inch drawings that feature wispy, minimal clusters of crudely drawn round shapes in graphite layered on handmade paper. Cage traced these imperfect lines from his personal collection of stones, and he determined the number of outlines in each drawing, their placement in the compositions and the pencils used according to the principles of the I Ching.

Like those of his celebrated musical compositions, this systematic approach leans into indeterminacy, in which shapes intertwine in seemingly random ways that are actually governed according to their own logic. In the strongest drawings on view, varied line weights and shapes made by utilizing pencil of various lead grades create depth, while a drawing like R 2/2 (where R=Ryoanji) (1983) only uses two different pencils, resulting in a comparatively flat and dull composition. Overall, Cage’s endeavor has a pleasant, enigmatic pull; however, his outsider’s perspective into a different culture is apparent. The utilitarian employ of the I Ching feels somewhat dated and superficial, informed by a desire to use it as an innovative tool for creative output that, while important in its heyday, does not consider Cage’s relationship with the text or its history.

John Cage, 3R-17 (Where R = Ryoanji), 1992. Courtesy of CASTLE and the John Cage Trust.

By contrast, with works informed by the traditional Chinese ink-painting techniques she learned during childhood, Zheng overtly harnesses the I Ching by physically embodying its iconography through engrossing colors, compositions and material. No. 12 and No. 50 (all works 2023) are rendered with the lined hexagrams of the I Ching in ink on sheer silk, and luminate vibrantly. No. 50 takes on a deep purple background with lighter I Ching hexagram diagrammatic forms on top, while No. 12 has a translucent, jewel-like amber background and rusted bronze bars in front.

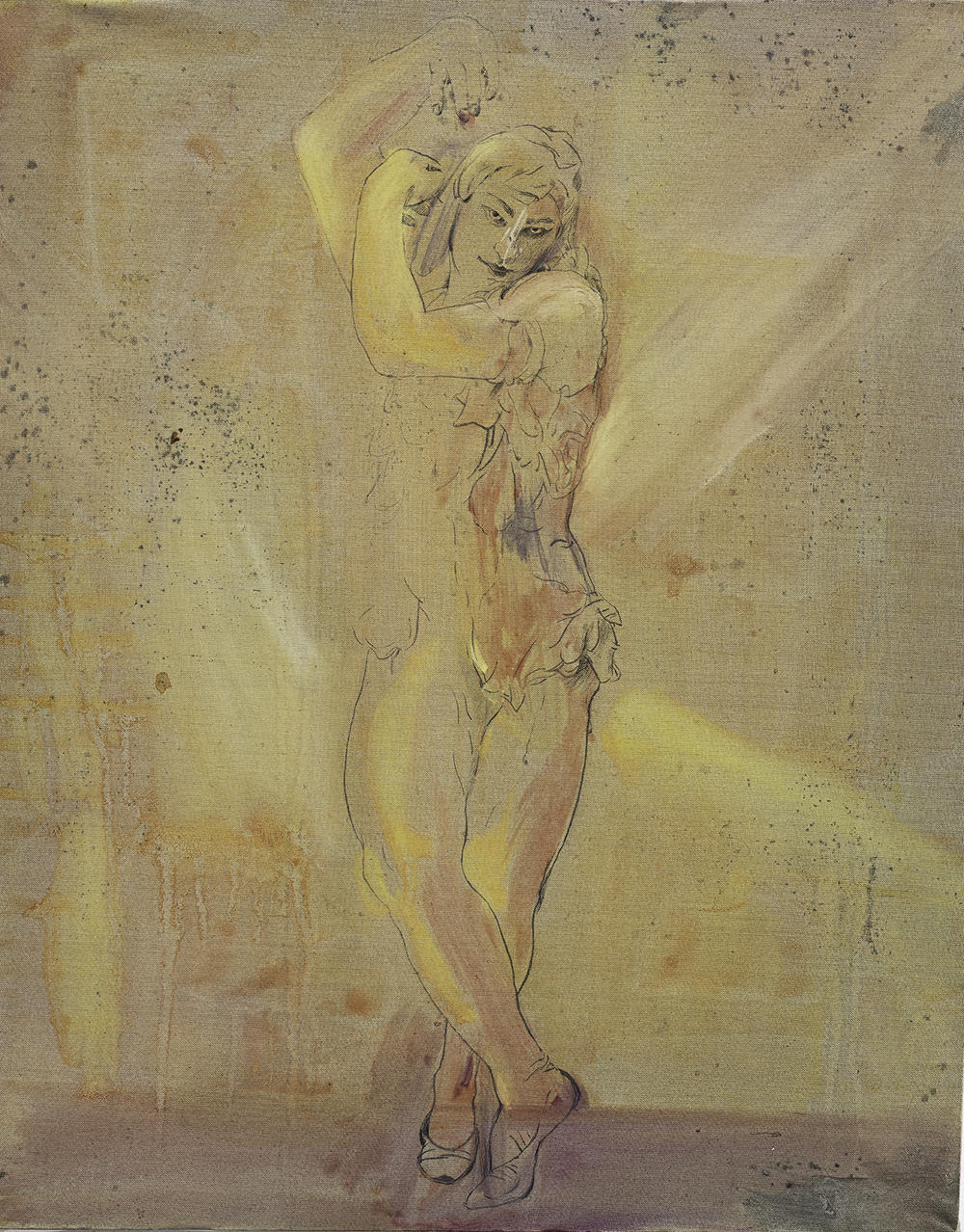

The I Ching also inspires Zheng to create abstract and figurative forms that conceptually, albeit cryptically, reflect the divination tool, as with two untitled, abstract works that resemble amorphous goop. Untitled (Nijinsky) suspends a loosely rendered dancer within a glowing yellow-orange background, their arms seductively raised. How Zheng connects the Russian dancer to the divine properties of the I Ching is opaque but reveals her ability to use it for intriguing and deeply personal interpretation. Although not intended or placed in opposition to Cage’s drawings, Zheng’s five works offer a more multifaceted, open-ended and compelling use of the text, upending any notion of the emerging artist standing in the shadow of an influential figure.

It could easily been have vexing to comprehend pieces imbued with so much idiosyncratic meaning derived from a text that itself is famously esoteric. However, the restrained and intentional pairing that guides this show finds its ideal curatorial setting in the serene, sunbathed Victorian interiors of CASTLE’s homey apartment space in Hancock Park. “The Grasshopper Lies Heavy” encourages us to relax and understand that the wonder of these works lies not in our complete understanding of their meaning but in our register of them as evidence of artists contemplating their worlds.