The 1980s witnessed the specter of AIDS as it decimated a generation of queer men and many others. Some prevailed—artist Joey Terrill among them, though he wistfully noted in an interview, “Unlike my friends … I’m still here—working….” That sentiment sets a bittersweet tenor for his first exhibition at Marc Selwyn Fine Art. It’s a significant and sweeping survey of the quintessential Los Angeles artist’s decades-long practice. Fresh from his inclusion in the Hammer Museum’s “Made in L.A. 2023” biennial and organized in collaboration with curator Rafael Barrientos Martínez, the exhibition crackles with energy, loss and resolve. As a bonus, the gallery has produced a cheeky zine-like monograph of the show.

At the time, Terrill, a second-generation Chicano, embraced art, queer and pop culture— even if the prevailing institutional sentiment wasn’t always reciprocal. But the impact of Terrill’s early HIV diagnosis and a singular vision propelled him forward, undeterred. Influenced by artist and social justice advocate Sister Corita Kent, his approach was culturally erudite and politically critical: Utilizing comics, zines, prints and paintings, he created urgent yet approachable visual chronicles.

The 22 works range from the mid-1990s through 2023—some earlier pictures were lost and subsequently recreated for the exhibition. The show is smartly organized to give the art breathing room. Principally composed of acrylic, mixed media and collage, the largely autobiographical pictures encompass a wide range of themes—domestic scenes; critiques of the pharmaceutical industry (which Terrill and his peers widely believed capitalized on the epidemic for profit); queer machismo and the phenomenon of gay “clone culture”; erotic mise-en-scènes and homages to those felled by AIDS. It’s an absorbing and overwhelming milieu compelling the viewer on a voyeuristic, if daunting, journey.

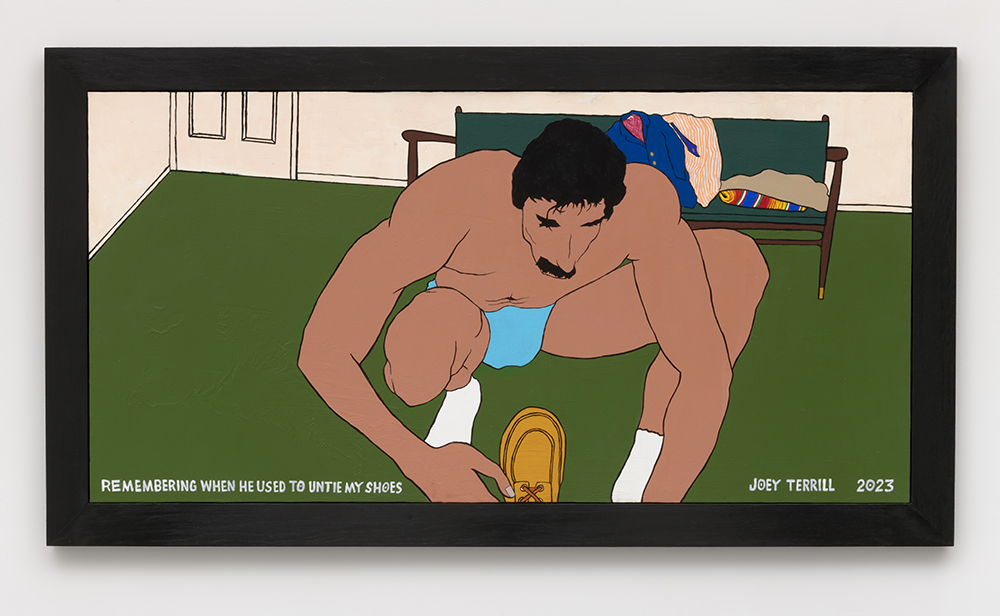

Joey Terrill, Remembering When He Used to Untie My Shoes, 2023. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer. Courtesy of Marc Selwyn Fine Art.

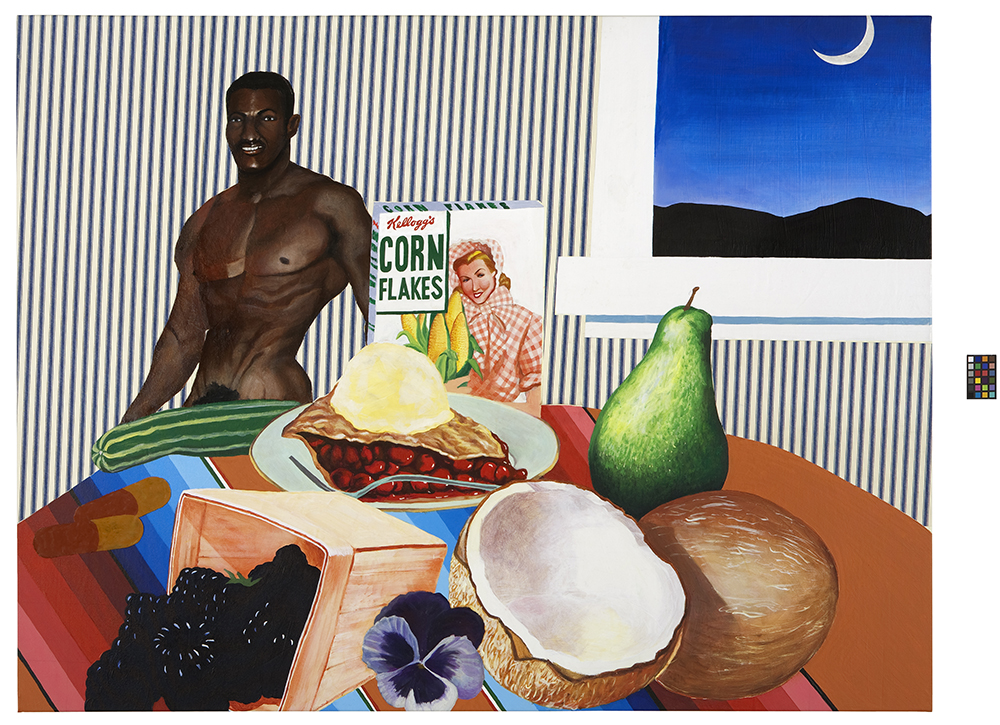

The still-life works are bright, flat with compositions that are often strikingly imprecise with slightly off-kilter perspectives that compel the viewer to remain vigilant. An early work, Still-Life with Sustiva (2000–01), depicts random elements of daily life on a tabletop covered with a serape, HIV pills, pan dulce and 7UP—markers of a domestic Chicano landscape. Terrill utilizes popular culture icons in much of his work, a choice also made by artists in New York’s Pictures Generation, who similarly utilized imagery of mass media and throw-away products. Remembering When He Used to Untie My Shoes (2023), shifts to an intimate scene: Terrill is concealed, save a lone foregrounded shoe, his lover attentively removing it. A serape—a recurring cultural anchor—appears tossed on a nearby couch. The image is at once erotic and ambiguous, a masterful composition of ritual and desire.

While the works in the main gallery are largely buoyant and affecting, the mood changes considerably in the smaller second gallery. At 54 x 128 inches, the ongoing project Fifty Christs (2023) is easily the largest work in the show. Composed of photocopies and acrylic, it depicts multiple images of Christ (after Caravaggio’s Entombment of Christ (1603–04)) in muted palettes, collage and various textures—a visceral and poignant homage to those lost to AIDS. It’s an arresting commemoration.

What’s clear is that Terrill has mastered both medium and message with remarkable deftness. This is storytelling at its most intimate and profound.