When Push Comes to Shove (2015), take what you know and simply make—make objects, make observations, make connections, make people listen, make people think, make a doorway in which others can enter your world. Jeffrey Gibson’s approach to making fits perfectly into our contemporary discourse; it also distinguishes Gibson’s methods in regard to objects, aesthetics, culture, and his own art practice, which, like his life, is a true mash-up in the most beautiful sense.

“Like a Hammer,” the first major museum survey to focus on Gibson’s practice post-2011, marks a notable shift and a period shortly after Gibson nearly gave up art entirely. Eventually embracing the freeing moniker of maker rather than artist, Gibson emerged invigorated and liberated—no longer needing to conform to bounds of a traditional art practice.

Gibson’s work pulls from all things in his general orbit: his Mississippi Choctaw-Cherokee heritage and traditions, pop and queer culture references, modernism, fashion, and a general freedom in regard to both the exploration and usage of materials.

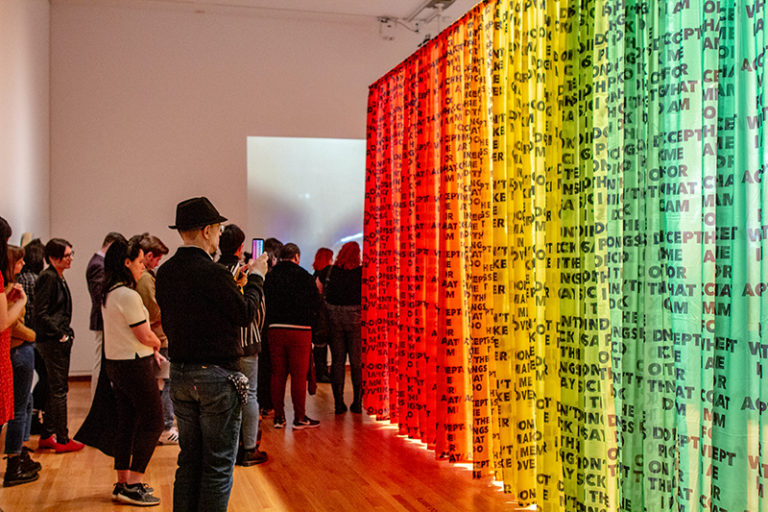

Installation view of Jeffrey Gibson: Like a Hammer at the Seattle Art Museum. © Seattle Art Museum. Photo: Natali Wiseman.

His equally familiar yet unapologetically foreign aesthetic juxtaposes traditional Native American techniques (beading, painting on stretched hide, and heavy adornment of objects) with a contemporary art ethos. References to historic and current art are unmistakable, with modernism, abstraction and the manipulation of found objects being at the forefront.

This exhibition, in its third iteration after traveling from the Denver Art Museum, is truly dense and covers a multitude of genres including sculpture, painting, installation and performance. The content, the social context, the implications, the materials used, the way in which works are installed, and simply the sheer volume (nearly 70 art objects of considerable size are on display) make it a lot to take in.

Viewing Gibson’s work in the context that he does, as a maker, is crucial to understanding it—a fact that is thoroughly explored throughout the exhibition. Gibson’s perspective on the studio and the process of making objects in mass is almost Warholian. This is evident most clearly in regard to his punching bags, beaded textual wall works and abstracted rawhide paintings. All are great in their own right, but seeing them en masse illuminates the artist’s process of production.

The adorned Everlast punching bags that Gibson is most known for are one of the many highlights. They are simply beautiful as objects, but even more so as an underlying idea and way of conceptually dealing with content. Each appropriated bag is heavily embellished with beading, verbiage and hanging tassel bits—taking much of their visual inspiration from Pow Wow regalia. As displayed at the Seattle Art Museum, hanging over shallow plinths, the viewer is left longing for more. Portions of phrases—that conjure powerful rhetorical effects—are legible from certain vantage points, but as the words cascade around the curvature of the bag, the viewer is left to fill in the remaining portions of both imagery and text.

With Gibson’s work also currently on view at the Whitney Biennial, he is an artist to keep an eye on as he continues to mashup the historic, the contemporary, and everything else in proximity.