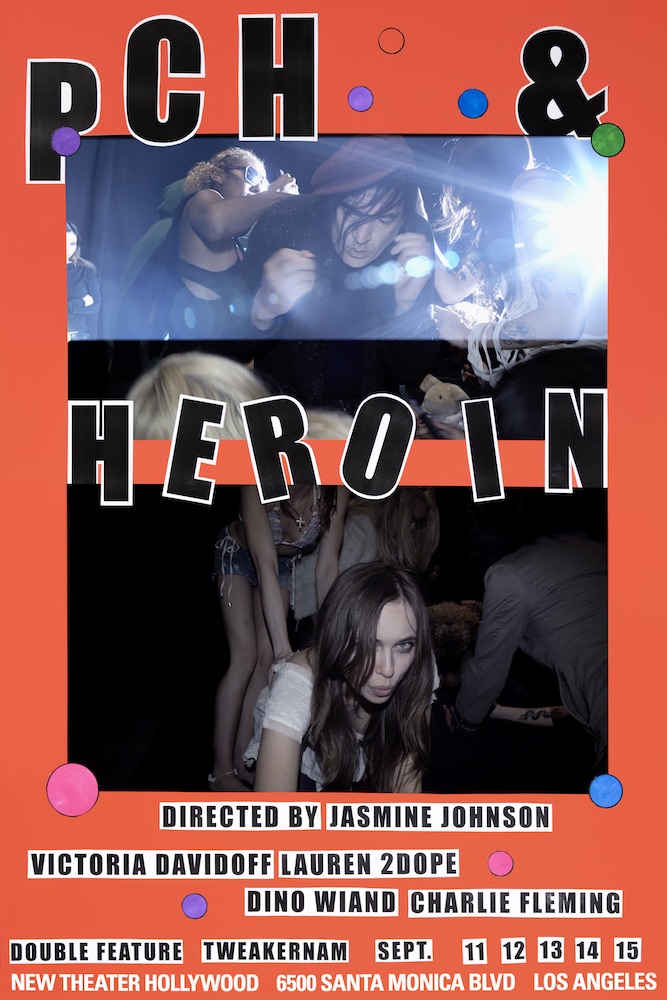

“All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.” Thus begins the most (and perhaps only) captivating scene from Jasmine Johnson’s film PCH & Heroin, which premiered recently alongside her film Tweakernam at New Theater Hollywood. The line, from Shakespeare’s As You Like It, is one we’ve heard so often as to make its recitation rote. Here, however, it’s not.

Perhaps it’s because of the dissonance. The actress on screen runs her lines, changes pitch, starts over. She speaks direct-to-camera: All the worl—All the world’s…Alllll the world’s a stage! She’s being filmed and she knows it. The footage is edited, cut with momentum. The whole scene is, as the monologue literally suggests, staged. Yet she’s also balancing on a tightrope-thin median strip on Pacific Coast Highway, with cars and buses whipping past, nipping at the tips of her hair and the hem of her skirt. Simply put: However contrived, the scene is also very real. It’s dangerous.

So, when she giggles, we wonder about nerves. When she shrieks at a speeding motorcycle, we consider adrenaline. And then we think of Johnson, too, the director operating the camera, teetering right there on the median strip: how sure of foot is she… and how aware?

Just as when Tom Cruise scales the Burj Khalifa, or Buster Keaton scampers in front of an oncoming train, the risk of real danger here is magnetic. It gives the scene immediate stakes. And, given the low budget aesthetics that imply the absence of trained drivers, stunt coordinators, film permits, or really a responsible producer of any kind, the risk communicates a degree of creative necessity—we didn’t have the resources to do it safely…but we did it anyway, because we had to.

In short, it’s about vulnerability—which manifests here as something like glee—in the face of intense precarity. It’s an idea Johnson would do well to flesh out and complicate through the remainder of the film, as it snags two of the more salient questions of the present moment, ones especially related to youth and online culture. First, what does it mean to be vulnerable in an era so heavily characterized by the art (or lack thereof) of the troll? And second, how do we move through a world so seriously inundated with precarity?

Johnson doesn’t seem to be interested in addressing these questions, though. Instead, she ditches the complication of the real for a style that leans heavily on oversimplified notions of artifice and proves content with using the As You Like It monologue scene as mere spectacle, a closed loop of thought to kickstart a program of films (and accompanying performance-cum-Q&A) that oozes insincerity at every turn.

Both films—PCH & Heroin and Tweakernam—feature casts of twentysomethings who look and act like Richard Kern models, brimming with Y2K allure and disinterested affect. The films radiate with a faux rebellion that the narrative devices used only serve to reinforce:moments of camp, scenes that break the fourth wall, and obviously fake practical effects.

Courtesy of Jasmine Johnson.

All this might make the films feel ambiently consistent, but it doesn’t elevate the work toward any significant resolution. Perhaps this is due to things being so technically unfinished: the audio tracks are poorly mixed, the color uncorrected, the editing senselessly arrhythmic. There are moments, too, where a neglect of practical skill detracts from the work’s thematic thrust. For example, in Tweakernam, during a scene set in a loft at sunrise, the camera noticeably operates on its autofocus and autoexposure modes, causing the action to rack in and out of focus, and the picture’s brightness to oscillate uncontrollably. Even if intended as a Brechtian distancing device, the strategy is redundant—we already hear Johnson directing the actors throughout the sequence, so the addition muddies the effect.

No matter, Johnson’s work shows promise. She has a knack for letting scenes breathe, for allowing us to watch as characters search for and inevitably settle into their positions of power (or lack thereof). In PCH & Heroin, for instance, we ride along with Dino, a bumbling wreck of a failed, middle-aged actor, as he’s sized up and questioned by Lulu and Lemon, the two siren-like, bikini-clad girls he “rescued” on the side of PCH. As the scene progresses, Dino’s air shifts from unsettled to endearing, and the girls’ from cunning to curious. Nothing’s forced; Johnson lets the actors take over, and, as a result, we’re engaged.

Johnson is skilled at crafting memorable set pieces, too. In Tweakernam (which spotlights the drug-fueled dynamics of a lawless bunch in a dystopic downtown New York) the hedonistic cast recites the “three essential truths of Tweakernam” (All is fair in love and tweak / Humility is the opiate of the masses / To deny beauty is to accept death) in a montage that skips from a city street to a rooftop to an empty loft and back again. The scene eschews continuity of time and place, but maintains consistency of tone and carries a hypnotic, musical charge.

Enticing as it is, though, Johnson’s elliptical approach in Tweakernam reads more as a stylistic flourish than anything else. It’s a direct graft of Harmony Korine’s “liquid narrative” method—popularized in his cult hit Spring Breakers (2013)—without the conceptual foundation to support it. Korine uses the montage effect to emphasize character transformation and amplify the absence of time, Johnson seems to use it…well…because Korine used it.

Courtesy of Jasmine Johnson.

To explain this all away—there’s always the “Well, that’s actually the point” defense, and it seems like Johnson and New Theater are prepared to make it. In promotional texts for the show, they lean into the unfinished-ness of the work, casting Johnson as something of a ringleader of commotion, who pulls it all together at the last minute, re-editing the films each night “in the greenroom, or the lobby, or on the stage itself,” just as the audience files in. The performance bits that bookend the films, too, are equally protective: actors remain in character, winking their way through Q&A skits that bubble with compulsory conflict and irony. Even the cast bios in the playbill read with this hedging insincerity: Johnson’s blurb, for example, is only one sentence: not only did she not “reinvent the wheel,” it states, “she doesn’t even know how to drive.”

“That’s actually the point” might actually be valid. New Theater’s founders—Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff—have spent the last decade documenting the goings-on at their venues and repurposing that material into collaborative projects of their own. This fall alone, the duo will present a film at The Hammer, a performance at REDCAT, and photography at Okey Dokey Konrad Fischer, all devised from the life that inhabits their theater. Henkel and Pitegoff don’t act as conventional exhibitors or proprietors but rather as writers and directors spinning a web out of other artists’ threads.

Maybe they need the chaos of a last-minute edit. Maybe they simply need the archetype of an It Girl (Johnson is most well-known as an in-crowd party host). Maybe they need something else. Who knows.

Until we know how Johnson’s work filters into Henkel and Pitegoff’s larger narrative project, evaluating its “point” is a necessarily futile affair.