Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Diva Corp

-

Alex Israel

at GagosianTo prepare for his current show “Noir” at Gagosian, Alex Israel claims to have walked about fifteen thousand steps per day around Los Angeles. This is highly unusual and, honestly, suspect. As the saying goes, no one walks in LA. Yet Israel insists on it and says that all this walking clued him into the more subtle, textured aspects of the city —things “[he] wouldn’t ever clock from the car window”—which ultimately informed his paintings.

In an attempt to better understand Israel and his work, I, too, began taking seven-mile walks around the city, daily: Van Nuys to Canoga Park, Glendale to Alhambra. El Prado to Sunset Tower. And so on and so on. I did my best to see the city as I imagined Israel would. I got into character—Alex Israel, wunderkind artist—and adopted that carefree, near-smug affect I’d seen in all of his portraits online. I did things that I thought he would do: I wore Ray Bans, smiled at nothing in particular, and listened to songs from mid-2000s iPod commercials. Slowly but surely, I started to feel cool and unhurried, the star of my own private sequel to Nic Refn’s neo-noir Drive: Walk.

Such a confident approach gave me clarity, and I realized that Israel was right. After seven miles of walking per day, you do start to notice the city’s hidden textures. Most obviously: for all their disuse (or perhaps because of it), the sidewalks are remarkably perilous, so full of fissures and crags that even a brief daydream comes at the cost of an ankle.

Alex Israel, “Noir,” installation view, 2025. Photo: Charles White. Courtesy of Gagosian. LA’s terrain, it turns out, is not easy. So, I’m surprised when I finally arrive at Israel’s “Noir” in Beverly Hills (by way of the Sherman Oaks Galleria, a four-hour walk through Benedict Canyon) to find a suite of paintings illustrating the exact opposite.

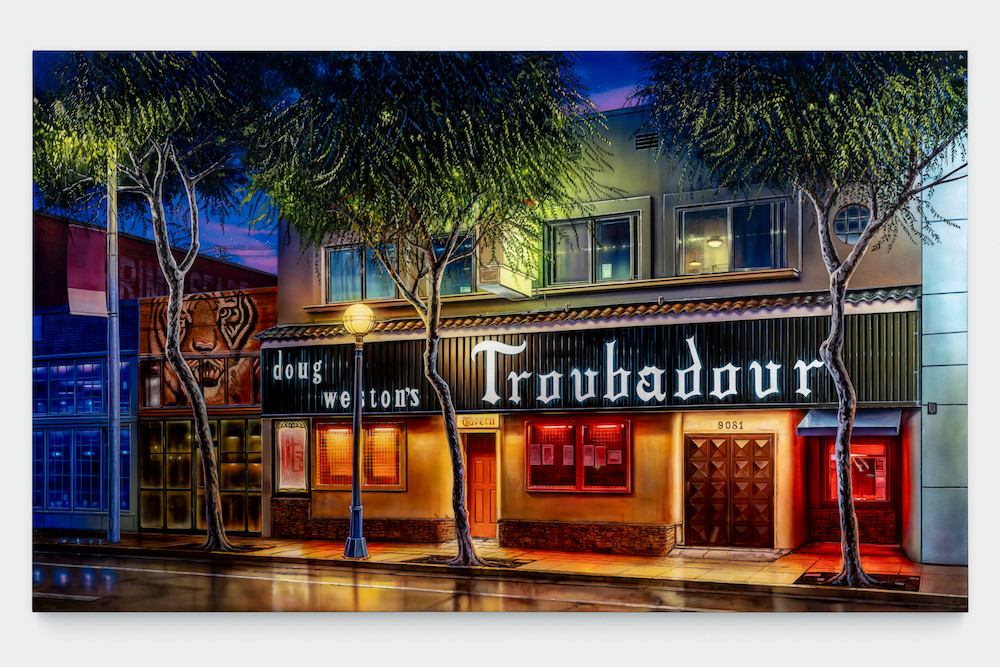

Apparently, Israel’s LA is easy. His paintings depict LA landmarks, both well and lesser-known—Chateau Marmont and the Troubadour, but also Trashy Lingerie and Hollywood Liquor—so completely awash in golden-hour purples and pinks that they’d fit neatly into one of Damien Chazelle’s La La Land dance numbers. Streets are glassy. Lights splash. Cars and people don’t exist. Notably: everything works. That is to say, as in Chazelle’s film, the city in these paintings is frozen in pure fantasy, in an artificial memory of what LA never was.

But that doesn’t mean they aren’t true.

Sure, everything here is totally contrived. Yes, the paintings were made on the Warner Bros. lot (where Israel keeps his studio), an iconic factory of cultural engineering. Yes, they were painted not by Israel himself, but by his ostensible assistant, the last remaining artist in Warner Bros.’ Scenic Art department, a place once known for painting the backdrops that manufactured cinematic reality. And yes, they’re untethered from time. Showroom, for example, depicts the Googie-style Casa de Cadillac dealership in Sherman Oaks with an Escalade dating to 2021; Gas Station shows the Beverly Hills 76 – a Mid-Century Modern wonder – with the price of a gallon at $1.59, situating it sometime around 2001 (though possibly earlier, since that specific station runs hot), yet with a pump model from 2020; and Chateau Marmont presents us with an Angelyne billboard that first appeared in the 80s, alongside an Apple ad from the mid-aughts.

Alex Israel, Troubadour, 2024. © Alex Israel. Photo: Josh White. Courtesy of Gagosian. But Israel isn’t trying to hide the artifice. He emphasizes it every step of the way – in lore, process, content and color. Some of his paintings’ dimensions are even directly proportional to cinema’s 16:9 widescreen ratio, and others to the billboards that dot the Sunset Strip, once again pointing to that which is constructed, sold, and nominally fake.

It’s precisely because these paintings are so wholly contrived that they become true. Israel leans into the city’s cliché—its fakeness, its artificiality—to highlight its depth. Vapid, you say? How about we empty it out entirely, then smooth it over and paint it like a static backdrop on a soundstage? The move is clever and conceptually sound, and it allows us to at once realize the incredible familiarity we have with our city, while also recognizing its impossibility. To live in LA is to constantly wake up from a dream you’d rather remain in. It’s not so much nostalgia as it is the stuff of romance, and of tragedy.

The paintings don’t go much further than this, and I’m not sure they have to. I could, however, stretch the show a bit further and note the fact that, at their most fundamental, these paintings are glorified depictions of LA real estate, which happens to be the source of Israel’s family fortune (his father is the developer Eddie Israel). So, while there is a base note of reverence throughout, maybe there’s also a tinge of guilt by association, of complicity. After all, these landmarks and their iconic features, not to mention the subcultures associated with them, will inevitably get lost in the very wave of real estate development that allowed Israel the opportunity to paint them in the first place. In other words, without this city, these paintings wouldn’t exist, but without these paintings, perhaps the city would.

Alex Israel: Noir

Gagosian

456 N. Camden Drive.,

Beverly Hills, CA 90210

February 6 – March 22, 2025 -

LESS THAN ZERO

On Risk and Art in Los AngelesI’m at a bar in Palmdale and it’s nearly empty. From where I am sitting, I can see two men playing chess. Or, rather, they’re not really playing—they’re afraid to make a move. It’s Pawn to E4, followed by the all-too-familiar analysis paralysis: finger steadies the piece, eyes tighten, neck cranes and turtles to check for danger, and then…Pawn back to E2. Let’s start again. Every move never happens, just like this.

It’s a riskless game, and stagnant, and it reminds me of the state of the arts in Los Angeles.

Since forever, LA has been about risk. We tell big stories on big screens about success against all odds. Our stars come from nowhere, move here on hayseed budgets with bindles full of aspiration and little else. Our freeways host the most spine-shearing car chases in the world; our sports are considered extreme, our politics radical, our drugs potent; and, recently, we’ve been reminded that we all essentially live in one big pile of kindling that’s oh by the way right along the San Andreas Fault.

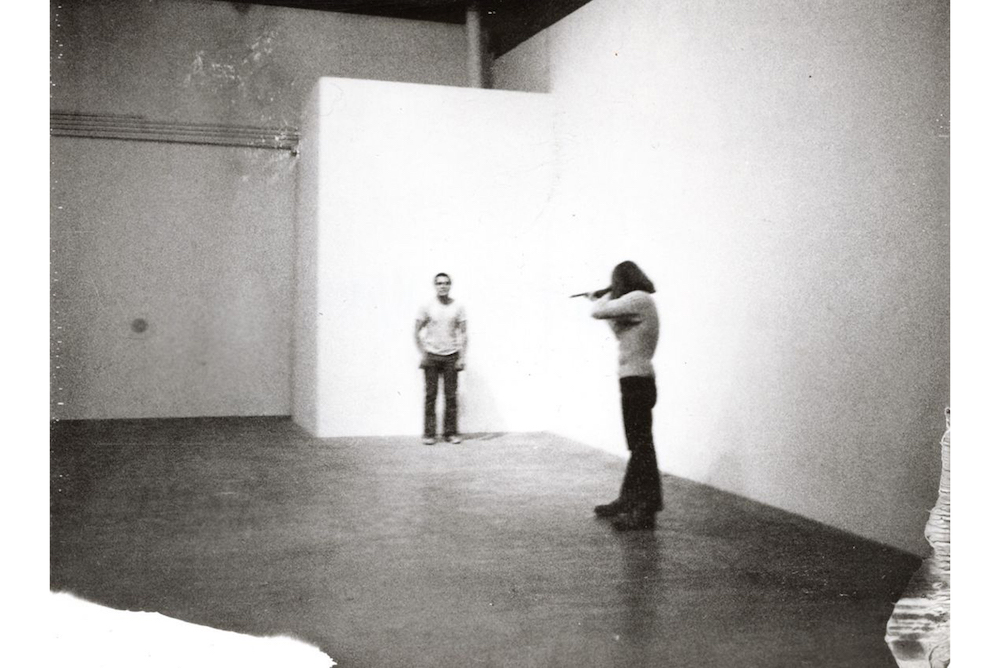

Chris Burden, Shoot, 1971, at F Space in Los Angeles. LA’s art is no different, at least historically. In the ’70s—amid Nixon, Vietnam, assassinations, moon landings and riots—Chris Burden had himself shot and crucified (Shoot, 1971; Trans-Fixed, 1974), Barbara T. Smith had sex with three men in one performance (Feed Me, 1973), Pippa Garner flipped a Chevy’s chassis and drove it backwards across the Golden Gate Bridge (Backwards Car, 1974), and Paul McCarthy fucked a bunch of raw hamburger meat with a hotdog up his ass, and videotaped it for everyone to see (Sailor’s Meat (Sailor’s Delight), 1975). At the same time, CalArts, as we know it, opened, and counted among its faculty one artist who burned all his paintings (John Baldessari), one who called twenty minutes of blank film a finished film (Nam June Paik), and another who believed that artists should stop making art altogether (Allan Kaprow). The history of LA art, of course, is far more complex and diverse, but this is the genesis of its popular spirit, one that plumbs the depths of taboo and skewers convention.

That spirit, however, has faded. LA art is staid now. Maybe all art is. And it sort of makes sense, too. Up until very recently the art market has been healthy, even booming. But memories of 2008’s Great Recession linger in the rearview, so despite the upswing, a tendency toward stability, toward the sure thing, is understandable. It’s also unfortunate because the sure thing is categorically anti-risk. It calcifies convention: Institutions get comfortable, galleries follow, and artists end up having to choose between satisfying a mandate to exhibit or not exhibiting at all. To rock the boat is to threaten the art world’s prized equilibrium, so little-by-little all movements of any kind are discouraged, until the boat stops moving altogether and things become inert.

Take Jeffrey Deitch’s recent “Post Human” show, for example, a reprise of his 1992 show of the same name. One look around and it’s clear that the most challenging, insurgent works in the gallery—let alone the city—were made yearsby artists currently in their 80s, or who are now even dead. I’m thinking of McCarthy’s Garden (1991–2), of course, Charles Ray’s Family Romance (1993), and Cady Noland’s Rotten Cop (1988), but there are others. Even some of the more striking contemporary work—like Josh Kline’s Aspirational Foreclosure (Matthew / Mortgage Loan Officer) (2016) and Ivana Bašić’s I will lull and rock my ailing light in my marble arms #2 (2017)—“shocks” in the same way that American Psycho or Marilyn Manson shocks, which is to say, only to viewers still living in the 1990s, who haven’t discovered the internet yet. In other words, the best new works here are old hat… pastiche, even.

And that’s the good stuff! Most art shows in LA are about as avant-garde as a corporate happy hour, except without the funny business from Kyle in accounting. Our schools, too, are factories of modest work—CalArts and UCLA, yes, you—training artists to avoid risk, or at least render it invisible, by using concepts like opacity, camouflage and misdirection. At one point, these approaches were an effective counter to the art world’s commodification of difference. The many social justice movements of the 2010s spawned a market that valued marginality so long as it was legible in the work. That is, artists were encouraged to prove it—their identity, their culture, their trauma—and to be explicit enough about it for it to sell, which quickened a roundabout march toward reduction and stereotype. An opaque approach then, in theory, protected the artist’s subjectivity from the capital forces seeking to exploit it. However, it has evolved. More recently, opacity has been used as a tool to avoid rocking the proverbial boat, regardless of identity: Say what you want to say, but make it illegible, and position it juuuuust right. At least, artists can then maintain some degree of integrity without sacrificing career advancement. However useful, these strategies aren’t pioneering or revolutionary: David Hammons, for one, made an entire career out of them, starting in the ‘70s.

“Ha Ha Place” at Leroy’s, 2024, exhibition view. Photo: Evan Walsh. Courtesy of Leroy’s. Nevertheless, François Ghebaly gave us “Scupper” this September. If there were ever a group show that captured the preferred mood and approach of LA’s MFA high command, this would be it. Apart from some notable names, many of the artists were recent grads, and almost everything was so opaque that the gallery had to provide a paragraph-long explanation for each work in the exhibition packet. For the uninitiated, this is extremely rare, even for conceptual art. A good rule of thumb is more precision, less text, and here we had ten pages. It proved necessary, though, as the artists gave us very little agency as viewers, scant clues with which to decode the work. A slab of grain here, some discarded concrete there, a few street bollards in the corner—that was pretty much it.

The problem wasn’t merely that the art lacked an aesthetic punch or a clever turn of material, and it wasn’t that it required texts to complete its meaning. (This is the name of the game in conceptual art, for better or worse, and has been for some time.) No, the problem in “Scupper” was a new one, one born out of a careerist climate specific to now, and out of the tepid approach to artmaking it engenders. Here, the issue was that the texts themselves were the opaque artwork, totally separate from the work in the gallery. These texts were carefully crafted and chock-full of criticality, sure, but really amounted to little more than fail-proof language games that traded in an erudite brand of nihilistic doomcore, so masterfully idle that they too should’ve had supplemental texts.

Ask around and you’ll get all sorts of excuses: Things are precarious, many will say, No one wants to lose an opportunity. They’ll point out that audiences want to be soothed, that “challenge” is a thing of the past. Some will blame a culture of fear around voicing dissent, driven by the pettish mores of galleries and the people that run them. Others will point out that risk-taking is rare—after all, it’s risky—so we can’t expect much of it, and still others will argue that risks are being taken, that for some artists even existing is a risk (seriously, this has been said!). Professionalism, millennials and the algorithm are reasonable scapegoats, too, and of course it wouldn’t be the art world if the granddaddy of them all—capitalism—weren’t subject to some blame, ditto with the patriarchy and white supremacy.

It all boils down to anxious artists overtrained to overthink. Timely, relevant moves simply do not happen. As a result, an art world that was once ahead of culture and leading it, now lags far, far behind.

… And yet there’s hope!

Recently, small pockets of experimentation have taken root in LA. Many of them, it’s worth noting, are alternative spaces with much lower overhead than their commercial counterparts (but not all). For example, Public Notice, a gallery no larger than a few closets, beneath a house in Silver Lake, mounted a spate of anti-precious shows last year that added some attitude to a very buttoned up scene; Leroy’s (in addition to being somewhat of an architectural risk) continues to throw shows at the wall to see what sticks, and a lot of them do; Tiffany’s and Quarters, two similarly small spaces operating more sporadically, often eschew the over-considered in favor of unbridled instinct and pathos. Sometimes, it’s enough to simply let art happen as SALA did this past summer in a rundown house at the top of a hill in Mount Washington, or as Emily Lucid did in her anarchically curated “EDEN” show at LAST Projects in December, or as Nora Berman does almost daily on her SparklyMiracleZONE Twitch stream. Even revivals of work by artists like Ron Athey at Murmurs and the many at Deitch’s “Post Human” serve to spark the notion of risk’s possibility.

“EDEN” at LAST Projects, 2024, exhibition view. Courtesy of LAST Projects. In every case mentioned above, the approach to exhibition-making more closely resembles a game of tennis than it does a chess match. In a system like this, things are faster and looser, and more uncontained. You set your feet as best you can, you take a swing, you play with pace. The ball might not go where you want—it might not even make it over the net—but good news: It’s coming right back at you, right now, so get ready. There’s slippage, mistakes are made, nothing is perfect, yet things keep moving. Momentum takes hold. And that’s the point.

Now, the tennis approach isn’t risky in itself. But, if we’re to recognize reputational and capital concerns as two fundamental deterrents of risk-taking, then working smaller and with more frequency necessarily dissolves the gravity of each individual exhibit. Then, artists can test the waters, update ideas at low cost, and, frankly, be unprofessional. The perception of things matters less, so there’s no need to hide, no need to over-frame, no need to be precious.

It’ll all sing with energy when you care just a little bit less, when you’re forced to go off-script and react, when you do it yourself, and fast. That’s when ideas will rally and come alive, and when we’ll get the unexpected.

-

Olivia Mole

at GattopardoThe shower scene in Psycho. You know it, everyone’s seen it. Go to the end. We follow a trail of blood and water through the tub, then push in as it swirls down the drain. In this moment, always, I beg Hitchcock to follow the zoom, to continue completely down the drain… to enter the void entirely! Instead, the shot dissolves to another of a lifeless eye, and we telescope back out. We never enter the drain.

This is the feeling that overwhelms Olivia Mole’s “Nocturne,” one of almost reaching exactly what it is that you’re after, only to have it soften into something else entirely. If you’ve felt this feeling before, it was likely in a dream, or possibly as a word slipped from the tip of your tongue, though it may have also been in a moment of love. Fine art rarely captures this feeling—at least not what we’ve been seeing lately. Even at its most oblique, today’s gallery-bound art tends toward the definitive, the unencumbered, the essentialized. Nocturne does not, and that is good.

Technically, the show is one work, Dopesheet Batman Ep VI, made up of seven “islands” of material, each grounded on a patch of industrial-grade, purple carpet. At times, objects are in motion—two inflatable projection screens tangle as they bloat alongside each other, filling with air; an oscillating fan periodically blows an opaque acrylic sheet over the mirror behind it; a mound of stuffed figures and camping chairs rotates on a turntable. There is noise and music and light, and three projections run at varying intervals—two lo-fi animations of the Charmin Bear and one text-based video with a corresponding spoken-word audio track. At the center of it all, practically hidden by the ostentation, sits a quiet bouquet of wilting tulips. The entire show cycles through every twenty minutes.

Olivia Mole, “Nocturne,” 2024, installation view. Photo: Chris Hanke. Courtesy of the artist. It’s all catch-as-catch-can, especially when it’s all moving. So much information, so much material. So much syncopation, too. A series of startling and then’s. You’re watching the silent video of Batman bear, and then the shrill spoken-word piece rings out, and then you catch your distorted reflection in mirrored acrylic, and then the moon bounce-like projection screens start to inflate, and then that fan turns on again, and then you finally make it over to read whatever it is that Mole has left Xeroxed on that table —evidence, perhaps?—and then the whole funhouse powers down altogether. Lights go off, things deflate, silence.

…yet, still, those tulips wilt. It’s the only part of the show that doesn’t stop, a punch unpulled. If we’re talking Psycho shower, the tulips—should we notice them—release us to the drain completely.

Considering the cyclical pomp and wreckage, one could easily interpret the show on purely systemic terms. A poetic indictment of the machine of so-called progress. Mole makes sure we don’t miss it, though. Her exhibition text consists of a single quote, uncredited, from the 19th century philosopher G.W.F. Hegel (“The owl of Minerva spreads its wings only with the falling of the dusk”), a sort of lamentation for man’s inability to understand history except in hindsight. Further, she summarizes her

materials list—which includes “Stars and Stripes Forever” by John Philip Sousa (the American military march composer, recorded in Independence, CA) and USA flag carry-bags—with the phrase, “A spell for the end of empire.” Seen through this lens, the show is one of many in recent memory that takes on the spectacle of late-stage capitalism in the United States, documenting the twilight of a system built for the system’s sake, rather than for the people in it.

Olivia Mole, “Nocturne,” 2024, installation view. Photo: Chris Hanke. Courtesy of the artist. The explicit reference to empire, though—while formally incidental—becomes somewhat limiting when it serves as the only given frame for the show. It preprograms an otherwise labyrinthine installation toward a singular, simplified read; it gives us the right answer. And that dampens what is otherwise one of the exhibit’s greatest strengths: the agential wrinkle. Nocturne’s design requires that we situate ourselves in the rubble, that we move and decide rather than merely observe. As intentionally distracting as the show might be, almost every piece reflects back an image of the viewer to themselves—sometimes obstructed or distorted, often fleeting—via mirrors, acrylic sheets, or glass. This is deliberate, no doubt: we, as individuals, are implicated in our collective fate, and it’s up to us to notice precisely when and how.

If nothing else, “Nocturne” is a site of play or, as the Diane di Prima scanned text on one table makes mention, “a kind of detour” that breaks away from a more linear understanding of the world. The show pushes us to associate and connect. We sharpen our ears to hear through the dissonance, we meander about on a hunch, we turn just in time to see the mirror before the lights go off. Mole creates a playground that perpetually rebuilds and deconstructs, through which we can observe ourselves and perhaps even our conceits. In a demanding, yet dynamic way, “Nocturne” reminds us to be alive in time, and to notice it.

-

Aria Dean

at Château ShattoIn her still-young career, Aria Dean has shown a remarkable knack for giving the institution exactly what it wants: shrewd work that stings the nerve of the moment without quite stabbing it. In activating the virtual as a conduit for Black radical thought, Dean’s interests dovetail nicely with the art establishment’s current (though fading) focus on political and identity orientation, as well as its recent (though tepid) embrace of post-internet work.

What Dean gives us in “Facts Worth Knowing,” however, is a significant departure. What she gives us is an artist on strike.

Up to this point, Dean’s output has been explicitly tied to Blackness, Afropessimism, and racial capitalism. Yet there’s no mention of any of that here, which is curious given the show’s association with Intolerance, D.W. Griffith’s 1916 epic. (Yes, that Griffith of Birth of a Nation notoriety, once the father of American cinema, now its maligned racist uncle). Instead, Dean, via the show texts, tells us to consider minimalism and form and the perception of sculpture in space and time (recalling Robert Morris’s 1966 “Notes On Sculpture”). These currents crested in importance in the Minimalist era with artists almost exclusively white and male, now old or dead.

Dean’s omission of Blackness from her own show—at least in its expected, explicit form—is the nexus on which things turn. In other words, Blackness is (drumroll) the elephant in the room, and Dean acknowledges this by fragmenting, warping, and melting an elephant out of a discontinuous montage of black steel and bronze. She models her elephant, or the sum of its parts, off of portions of Griffith’s monumental (and notoriously abandoned for years on an East Hollywood lot) Intolerance set, using blueprints from the set’s appearance in the 2011 video game L.A. Noire to help accurately render her forms. Notably, that video game takes place in 1947, almost thirty years after Griffith’s set was razed. To add it all up, then: We’ve got a deconstructed representation of an elephant, modeled off of a digital facsimile of a replica of a statue of an elephant, from a time in which it never existed in a place that doesn’t exist (or exists only virtually).

Remember, though: You’re here to think about material, the text says, and temporality, and space. So, you try. You think about steel which structures, bronze which historicizes, both of which are certain and fixed. You note that the titles of the first three pieces, the Duchampian Bottle Rack-esque sculptures near the entrance, all mention armature or infrastructure or both, and, naturally, you wonder what exactly they’re armatures and infrastructures for. They’re implied frames, supports for real, true sculpture—the everlasting—yet within the frame of the gallery they exist as real, true sculpture themselves, simply because they’re here. Thus, the negatives that affirm the absent positive become the positives themselves, and the distinction between object and subject begins to slip, as does the consensus on which that distinction is built. Dean echoes this in the formatting of her exhibition essay, printed with a conspicuous border around the text, leaving the title of the show outside that frame, yet within another, hinting that the facts worth knowing in “Facts Worth Knowing” exist both ex- and in-frame.

Primed to think about the impossibility of the frame, we can read this work as Dean denying the establishment the conveniently packaged, readable show it wants, while alluding loudly to its absence. There’s a chance “Facts” is still on some level cynically catering to museum boards, the institutional darling engineering a rebellious streak. Or maybe it’s more of a newfound artistic obstinacy, an inversion of, say, Mike Kelley’s sardonic embrace of the apparatus’s expectation. More likely, though, Dean just came to realize that the work was starting to produce her, and she wanted out. No matter, the institution will happily devour this show, just as capitalism devours its discontents only to respawn them as commodities. It’ll find a frame, as it always has done—a frame that will, once again, limit the work, as it has always done.

Dean’s project here—the larger one, the strike—is a gesture at unlimiting. By questioning the productive relations of the art world, and in trying to avoid becoming synonymous with herself, she reminds me more of Michael Krebber, the (white) German conceptual painter, than anyone else. Krebber’s current show at Greene Naftali comes accompanied by a text that argues in favor of artists who seek rather than find. The latter is more passive, at times intuitive, and certainly yields fine results, but the text stresses that seeking—through its almost unsexy manifest of the attempt, of the unfinal—opens us to ideas about “where [art] comes from and what it is after.” Measured this way, Dean’s show reads an expansion of the field of art for art’s sake, an insistence on the uncertain terms that make art art.