Los Angeles painter James Hayward taught a USC graduate seminar in 1987. That was my introduction to him. He wasn’t much of a teacher, but he sure was a talker. He sat in a chair front and center in the classroom with his legs stretched wide open. When he would get excited by his own tall tales (which was most of the time), his long skinny legs would begin to flap back and forth wildly in rhythm to his lilting voice which got faster, louder and higher when reaching the climax of the story. He told stories about Richard Serra, John Baldessari, Brice Marden and Max’s Kansas City. With his good looks and charm, he could brighten up any dull opening. He’s an unassuming cowboy with the manners of a true gentleman, but he can also tell a vulgar joke with the verve of a drunken sailor.

These memories of the now-veteran abstract painter are running through my mind as I’m driving to Moorpark where Hayward lives—we’re going to discuss painting. I find myself giggling down the Simi Valley freeway, oblivious to the stunning desert view, recalling a distasteful joke that Hayward recently told at a Hammer opening—where everyone was getting hammered.

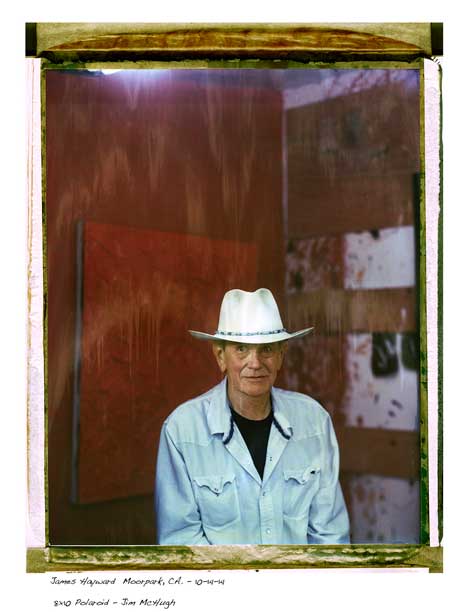

I pull off the county road onto a graveled entrance with a locked gate. I forewarn Hayward with a call, but receive no answer. Out of nowhere he appears with two shaggy barking dogs, looking like a craggy Clint Eastwood in a cowboy hat, with a stogie dangling between his fingers—although this stogie contained reefer (a minor detail). He apologizes for not having left the gate open and tells me that he couldn’t find his phone. Once he unlocks the gate I enter a wide, open green field and follow a cactus-lined path leading to his living compound: a studio, various other small buildings and a trailer in which he dwells. It is a clear day, and 50 miles out of LA you can feel a noticeable improvement in air quality. Everything is green and perky with the recent rare California rains, and the crisp December air makes for a wonderful mid-morning bucolic landscape.

I’ve always admired Hayward’s paintings; full disclosure, I own a small black one. A painter once myself, I respond to color and surface, and Hayward’s paintings fully satisfy both counts. His paint application and saturated colors are hypnotic and intense. So to talk only about paint (I realized I had my work cut out for me with his tendency to digress) is exciting, as his paintings have always exuded a raw passion through their luxuriant seductive surfaces.

When referring to them though, I am cautious to avoid the “F-word.” And by that I mean “frosting.” Hayward’s paintings have been referred to as the frosting paintings—and for obvious reasons, owing to his thick heavy brushstrokes—but Hayward calls them “monochrome abstraction.” He further explains, “People ask what does that mean—you know, lay people? I say, well basically I make one-color paintings of basically nothing.” Hayward laughs at his own joke, but he’s serious too.

Hayward, 71, has always been a nonrepresentational painter, right from the beginning at San Diego State. He won many prizes for his Hard Edge paintings. “I wasn’t good at drawing people. I was glad to discover at college that you didn’t have to draw people to be an artist,” he says laughing—although he confesses that he won a Smokey the Bear poster contest when he was 7.

But it was in the figurative paintings of Titian that Hayward discovered painting was about markings. “When I first saw late Titians in Rome, I was amazed how beautiful they were and how about marks they were.”

I ask if painting is a physical thing for him—I have this vision of him in his studio vigorously slathering globs of thick crimson onto a canvas with a paintbrush in one hand and a bottle of wine in the other. In my mind he’s wearing only his cowboy hat and cowboy boots, and a pair of red boxer shorts—the same color as the painting he’s working on—and Hank Williams is blaring in the background. He answers, “The physicality is part of it, but the heart and soul of it is the marking. In my monochromes I try to avoid there ever being a special place. There’s no chosen place. It’s totally proletariat, the marking. I want the corners to be as important as the center and I want every mark to be equal in terms of importance. Ideally, the last marks just kind of blend into the earlier marks and disappear.”

Hayward pauses and takes another drag off the joint he’s had going throughout the conversation. He continues, “[Dave] Hickey talks about how he loves looking at my work because his eyes surf across the surface of the painting and you never get stuck. You just keep weaving through it and finding a new way to drop through.” I was aware that art critic Dave Hickey is an admirer of Hayward’s as he’s curated him in many shows. I ask Hayward if Hickey ever bought one of his paintings. “Oh, I was such a whore,” Hayward belts out excitedly as he exhales a puff. Then he tells the story about how Hickey called him up and asked if he would do a painting for him to hang above the couch for an Italian Vogue photo shoot. All his life he has avoided doing a horizontal rectangle. And for good reason, Hayward explains, ”I’ve always looked at the horizontal rectangle painting as a couch painting.” Not only did Hayward tell Hickey he had never done a horizontal rectangular painting, but he never has done paintings in increments of feet—“they’re simple-minded and kind of vulgar,” Hayward sniffs. “So I got back and asked would 33 x 77 inches (both numbers that I’ve used throughout my life) be okay? He says, that would be fine. ‘Blue?’ He makes sure to ask. I answer blue. And I made it, delivered it and we hung it…ahem…over the sofa,” Hayward laughs.

I ask him why his paintings aren’t referred to as AbEx? “Because the marks have no meaning. Each mark is (pause) they’re pretty much all the same. In a way it’s more like music than Abstract Expressionism. It’s like free-form jazz or something. It’s just marks piled up and piled up.”

AbEx or abstract minimalism or chromachords or, dare I say it?—frosting paintings. No matter how you slice it, it’s painting on a most pure level. Color fuels these gorgeous works, and the markings of a skilled painter yield a masterful work of art; the man behind it provides the soul.