Australian artist Patricia Piccinini’s world is inhabited by creatures that suggest genetic engineering gone awry or the infusion of sentience in hitherto inanimate objects. Her hyper-realistic sculptures combine elements of human form blended with those of animals, machines and plant life, raising questions about our response to beings who do not meet our expectations of normalcy. These hybrids, created from silicone, human hair, leather, fiberglass and other materials, are unnervingly convincing.

Piccinini represented Australia in the 2003 Venice Biennale and has since been widely shown internationally. Her confrontational, emotionally charged work has clearly struck a nerve, and her 2016 solo museum exhibition in Brazil was the second-best attended show worldwide that year. Her works span still and animated sculpture, installation, photography and film—along with a pair of giant hot air balloons representing lactating whales.

At San Francisco’s Hosfelt Gallery, her 2023 exhibition, “A tangled path sustains us,” placed various hybrid creatures in an immersive, diorama-like woodland setting based on California’s redwood forests. Piccinini is the visionary force behind a small team of creative collaborators that includes her husband, Peter Hennessey. One member is responsible solely for the rooting and placement of body hair—eyebrows, eyelashes and all.

I was recently able to Zoom with the artist, who spoke from her home in Melbourne, to learn a bit more about her background and what motivates her work. Born in Sierra Leone, she returned to her father’s village in Italy, between Milan and Bologna, at the age of three with her family, where she lived a “very secure” and community-oriented life. But when Piccinini was seven, life took another abrupt change with her family’s move to Australia. “When we migrated,” she says, “I experienced a kind of bewildering change of culture.” This early outsider feeling affected her deeply and continues to inform her work.

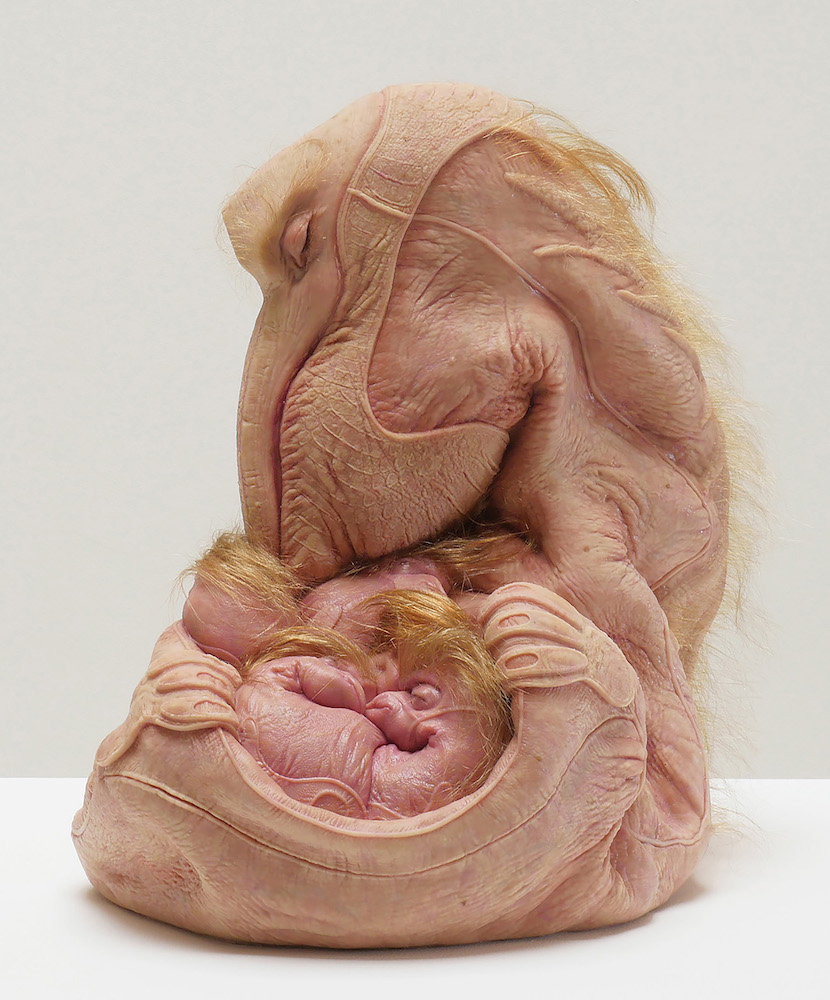

Clutch, 2022.

Her interest in a post-human worldview was sparked by an art class at the University of Sydney taught by Australian feminist Elizabeth Grosz, as well as Donna J. Haraway’s book, A Cyborg Manifesto (1985), which refutes traditionally held dichotomies as ill-conceived and outmoded. Haraway’s book emphasizes that advances in evolution, genetics and technology have blurred the boundaries between animal and human, natural and artificial, and human and machine. A feminist perspective, along with a deep empathy for all creatures in the world, is a key component driving her work. Much of the work considers the idea of care—for a child, a loved one, an animal. She is adamant about the beauty and significance of birth, and feels it is undervalued in our society.

Piccinini refers to her hybrid creatures as “chimeras,” the name coming from the fire-breathing creature in Greek mythology that was part-lion, part-goat and part-serpent. The cautionary tale of Mary Shelley’s Frank- enstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), was “seminal” to her work. “It’s really a story about bad parenting,” Piccinini states, “about a father who is unwilling to care for his son.”

One of her most visually and thematically complex works is the pelican-inspired Clutch (2022), part-bird, part-gestating mammal and part-cowboy boot. Piccinini’s tendency to throw in inanimate features adds an unexpected element that makes the sculptures even more bizarre, often offering a more humorous note. While some may find her creatures creepy, off-putting, or even horrifying, that is not the artist’s intention. She truly loves these misfits, as is reflected in the infinite care with which they are constructed.

Safely Together, 2022.

As the cowboy boot evolves into the head of the pelican, the evocative texture of the skin and boot are fused together seamlessly. The tiny, dewy-looking “boot-chicks” are cradled in the womb-like fold of the pouch. Piccinini is not one to shy away from celebrating the marvels of nature, including the deep folds and tender orifices so often off-limits in our culture. She feels that part of her strategy as an artist is to put people off a bit at first. As she admits, “Maybe they’ll find the work grotesque, but then they will get drawn in, and come to like or even love it as interest overcomes their initial resistance.”

Some works, such as Big Mother (2005), Safely Together (2022) and While She Sleeps (2021), are inspired by real-world events—a grieving mother baboon kidnapping a human baby, the relentless poaching of the pangolin, the only mammal with scales—or the hunting to extinction of thylacines, also known as Tasmanian tigers, perhaps unjustly accused of sheep-killing proclivities. These creatures are in so many ways one with us, according to Piccinini. They display strong emotional connections in an envisioned trans-species, post-human world. Rather than threatening, these beings display a haunting vulnerability and longing for acceptance, their freakishness acting as a metaphor for our own frequent experience of being “othered.”

The hybrid beings Piccinini creates, such as in the heartbreaking The Couple (2018), act as our avatars in an only slightly speculative world of “what if?” This work, which depicts a couple embracing in a tent, has been re-envisioned in an upscale apartment setting for the artist’s recent show “HOPE” at Tai Kwun in Hong Kong. Piccinini was excited to share news that it will be traveling to Jakarta later this year.

Reflecting on genetic experiments, and the close kinship of this procedure to the mashed-up body parts of Frankenstein, Piccinini asks, “What is our relationship to these creatures that we create? And how do we feel about them?” Of nature’s own ability to adapt in the face of adversity, she notes, “Out of a lot of negative things come positive things.” Piccinini’s own extraordinary work is one such hopeful note.