A procession of wooden plinths hold aloft groups of idol-sized sculptures, stout bodies with the hallmarks of Mayan figurines, whose torsos sport schematic rib cages, hearts and organs, and are topped with faces rendered in a contemporary style—portraits of migrants and asylum-seekers at the US-Mexico border whom the artist regularly sketches while they wait to make the crossing. This is “Caravan,” a series of sculptures and a short stop-motion animation in which they star—the anchor of a new exhibition by Hugo Crosthwaite in which he continues his decades-long process of documenting the personal experiences and individual stories of the human beings who undertake this perilous journey.

The sculptures are strange, haunting, surreal little things, and while one wishes there were more of them—like hundreds or even thousands, embodying even more directly the vast scale and overwhelming scope of the border’s circumstance—the family-size clusters arrayed in a pattern tracing the contour of the border region are nevertheless haunting in their evocations. Each group of four people centers around a fifth skull-headed figure, as though death were always with them, their constant companion on the voyage. In the animation, these figures are jostled and corralled and treated roughly, smuggled and shipped, and eventually released—it’s uncomfortable, and having viewed it, turning back to the ceramics again, they are further infused with the trauma of surviving the ordeal, their expressions of desperate determination given context.

Hugo Crosthwaite, Caravan Group No.16, 2022. Photo: Paul Salveson. Courtesy of the artist and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

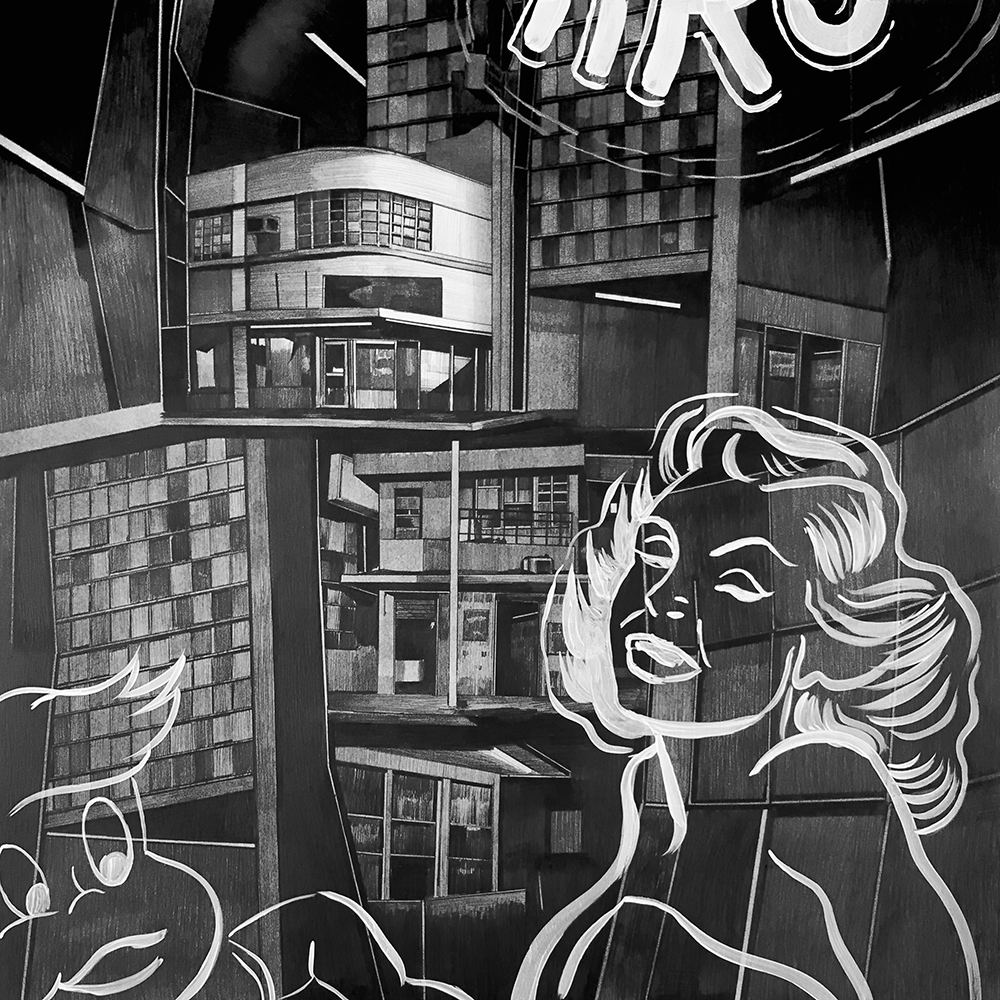

Two suites of new paintings expand the central theme in diverse, self-contained series that get deeper into other aspects of the immigration story. In the black-and-white artworks of “Borderlands,” charcoal, pencil and acrylic paintings on board, create a kind of chalkboard effect: meticulously rendered figures, faces and schemes of decaying urban density emerge from the low-light background. Gestural white-line drawings in a range of styles from block text to cartoonishness and vintage Pop-era advertisements hover above these noirish boulevards, creating moments of dissonance, romance, campy threat and broken promises.

Most surprising are the large-scale acrylic-and-oil stick works on canvas from the “Manifest Destiny” series in which—for the first time in 20 years—color plays a major role in Crosthwaite’s work, however with elements of the same lexicon of black-and-white drawings that lightly decorate the ceramics and densely populate the “Borderlands” paintings, as well as imagery more specific to both the desert landscape and icons of hope like the Statue of Liberty and the Virgin of Guadalupe. These are arranged in totemic stacks and layers against a chunky patchwork cartography of teal and orange—a grabby but queasy palette of hot and cold, earth and sky, that speaks to a state of mind and body in transit, in flight, in disorientation, in violence, in hope and in striving.