I’ve always found the word “gilded” to be slippery. On a literal level, it refers to the application of paper-thin sheets of gold leaf, a technique that’s been around for millennia. Not only does the process coat and protect ordinary materials like wood or stone, but it gives them a regal flavor. To “gild” an object, more often than not, means to deify or ennoble it. But not always. Gilding is a decorative process; it only deals with surfaces. So these objects can become associated with the deceitful and frivolous.

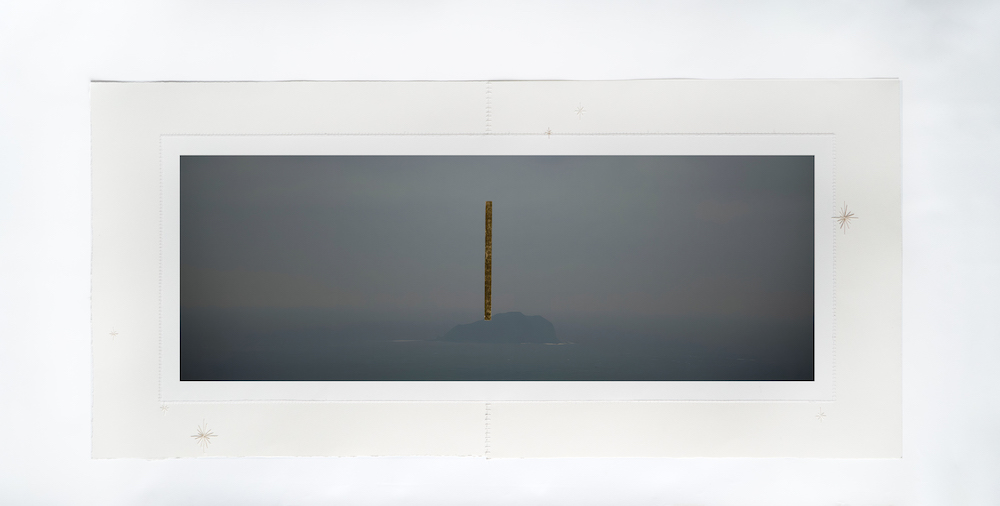

In “Gilded Consciousness,” Sabrina Che navigates this tension in a tightly focused show that examines the presence of divinity in a world where the self has dissolved. Using photography, sculpture, textiles and video, Che produces surreal forms and landscapes that straddle the boundaries between gender and biology, phylum and kingdom, and even organic and mineral forms. I mean that literally. The works in the show are linked through two leitmotifs––rocks (Che found many herself on hikes and solo wanderings) and gold totem-like shapes that appear, apparition-like, staked over beaches, tattooed on stones, or floating among purple jellyfish. (The gold, Che tells me, is No. 4 Tachikiri sourced from Japan––the same level of purity used to decorate Buddhist shrines.) In Gestalt (2023), a solitary rock, barely perceptible in the mist if not for a dramatic gold pillar, recedes into a horizonless ocean. You easily could dismiss the landscape as placeless or fake––the type of idealized, too-perfect scene you’ll find slapped onto screensavers or motivational posters. And yet, amid the fog, voidal grays and absent human presence, you can’t help but hear echoes of traditional Chinese landscape painting. Those artists, steeped in the idea of woyou, or ‘wandering while lying down,’ rarely painted real landscapes either.

Sabrina Che, Cradle 01, 2023. Courtesy of Great Art Space LA.

Che calls her sculptures “cradles,” although they have a lot in common with pooja mandirs: small, decorative Hindu altars specifically designed for the home. Yet here, wooden benches carved in zoomorphic forms become steeds for the stones, which Che elevates to the level of deities. (It helps explain the gravity-defying tension within Cradle 01, where a stone, meticulously anointed with a streak of gold leaf, rests calmly upon a precariously sloped wooden surface.) These small-scale devotional objects, where the animal, vegetal, and mineral kingdoms intersect, hint at cosmological orders that predate biological differentiation. Small wonder Che called these sculptures “cradles,” alluding to a primordial state of sexless innocence, before culture got in the way.

Much like Che’s “cradles” allude to the beginning of life, her “shrouds” evoke its conclusion––the term, after all, evokes the ceremonial cloth used to wrap the dead for burial. In contrast to the figurative forms that dominate much of the show, these pieces are pure abstractions. Constructed from paper squares hand-stitched to gampi paper and veiled with pale silk organza, the shrouds create warm, yellow-hued auras of imminence glimpsed on a molecular level, beyond consciousness and thought. It’s ironic, then, that gallery sits in the heart of Beverly Hills’ ‘Golden Triangle,’ where conspicuous displays of material wealth are on near-constant display.