Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: India Mandelkern

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Sabrina Che

Great Art Space LAI’ve always found the word “gilded” to be slippery. On a literal level, it refers to the application of paper-thin sheets of gold leaf, a technique that’s been around for millennia. Not only does the process coat and protect ordinary materials like wood or stone, but it gives them a regal flavor. To “gild” an object, more often than not, means to deify or ennoble it. But not always. Gilding is a decorative process; it only deals with surfaces. So these objects can become associated with the deceitful and frivolous.

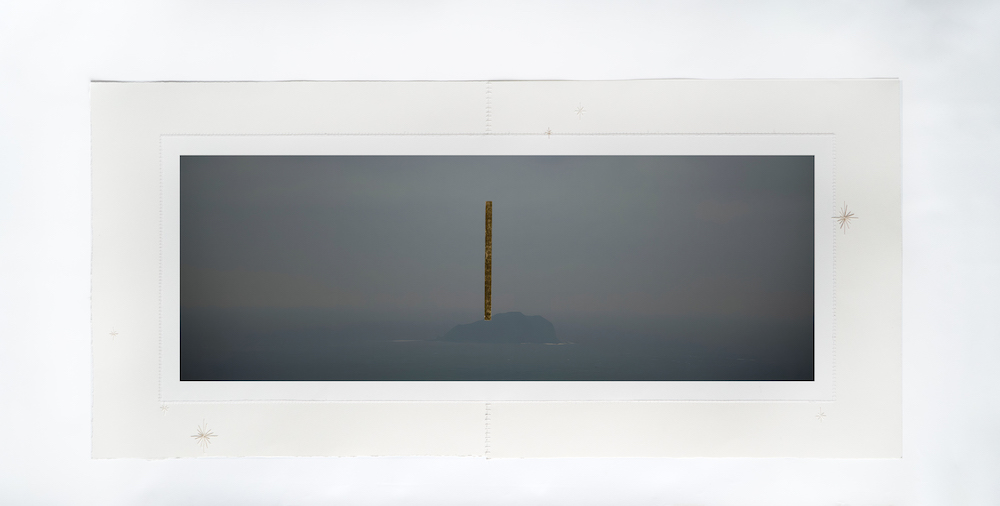

In “Gilded Consciousness,” Sabrina Che navigates this tension in a tightly focused show that examines the presence of divinity in a world where the self has dissolved. Using photography, sculpture, textiles and video, Che produces surreal forms and landscapes that straddle the boundaries between gender and biology, phylum and kingdom, and even organic and mineral forms. I mean that literally. The works in the show are linked through two leitmotifs––rocks (Che found many herself on hikes and solo wanderings) and gold totem-like shapes that appear, apparition-like, staked over beaches, tattooed on stones, or floating among purple jellyfish. (The gold, Che tells me, is No. 4 Tachikiri sourced from Japan––the same level of purity used to decorate Buddhist shrines.) In Gestalt (2023), a solitary rock, barely perceptible in the mist if not for a dramatic gold pillar, recedes into a horizonless ocean. You easily could dismiss the landscape as placeless or fake––the type of idealized, too-perfect scene you’ll find slapped onto screensavers or motivational posters. And yet, amid the fog, voidal grays and absent human presence, you can’t help but hear echoes of traditional Chinese landscape painting. Those artists, steeped in the idea of woyou, or ‘wandering while lying down,’ rarely painted real landscapes either.

Sabrina Che, Cradle 01, 2023. Courtesy of Great Art Space LA. Che calls her sculptures “cradles,” although they have a lot in common with pooja mandirs: small, decorative Hindu altars specifically designed for the home. Yet here, wooden benches carved in zoomorphic forms become steeds for the stones, which Che elevates to the level of deities. (It helps explain the gravity-defying tension within Cradle 01, where a stone, meticulously anointed with a streak of gold leaf, rests calmly upon a precariously sloped wooden surface.) These small-scale devotional objects, where the animal, vegetal, and mineral kingdoms intersect, hint at cosmological orders that predate biological differentiation. Small wonder Che called these sculptures “cradles,” alluding to a primordial state of sexless innocence, before culture got in the way.

Much like Che’s “cradles” allude to the beginning of life, her “shrouds” evoke its conclusion––the term, after all, evokes the ceremonial cloth used to wrap the dead for burial. In contrast to the figurative forms that dominate much of the show, these pieces are pure abstractions. Constructed from paper squares hand-stitched to gampi paper and veiled with pale silk organza, the shrouds create warm, yellow-hued auras of imminence glimpsed on a molecular level, beyond consciousness and thought. It’s ironic, then, that gallery sits in the heart of Beverly Hills’ ‘Golden Triangle,’ where conspicuous displays of material wealth are on near-constant display.

-

Disassembly Line

SPY Projects / Molly’s GarageIndependence. Freedom. Unchecked mobility. We’re quick to attribute these qualities to the automobile: grand, sweeping, all-encompassing statements that turn the machine into an intractable, totalizing force to be glimpsed from the outside-in. We think less about the car as a collection of private spaces that each play singular roles: The war room, the kitchen, the bedroom, the sex den, the place you hide the body.

“Disassembly Line,” presented by Pietro Alexander, Sasha Filimonov and Gabriella Rothbart, investigates these interior, personal ways in which we’ve come to understand our cars. Riffing off the butchering and packaging processes of late 19th-century slaughterhouses that helped give birth to the Fordian assembly line, the curators set seven artists loose on a 1998 Oldsmobile 88––letting them gut it, manipulate it, and remake it from the ground up––in order to poke holes in the supposed intransigence of industrial systems, and obliquely, the role of the traditional gallery.

For the car is the gallery: Engine, windshield wipers, gas cap, door handles, antenna––all its functional features (except the parking brake) have been completely stripped away. A geometric floral skeleton––a ceramic signature for which Iranian sculptor Yassi Mazandi has built a reputation––blooms out of the steering wheel. Sculptor Mannix Vega, who daylights as a mechanic, painted the exterior in a gold-flecked, black matte patina and sharpened the edges of the hood, not unlike the way you’d soup up a hotrod. Except it’s not a hotrod. The car no longer functions: a point underscored by the parking tickets strewn across the windshield. Constructed by Daniel Healey, who copied, traced and duplicated real citations with vintage Letraset sheets and printer paper, the tickets combine real names, addresses, and phone numbers with snide, sarcastic comments (Terrible paint job! She lost control!) (2021) They’re so banal, so convincing in their stern straight edges and red-and-white lettering, that you have to blink to remind yourself that they’re made by hand, and fall into the realm of art.

Courtesy Spy Projects. Pop the trunk and lift it up; you find two additional artworks. Ivan Rios-Fetchko’s Trunk (Hood) (2021), presents a quadriptych of landscapes: A vacant overpass, a concrete ribbon, a solitary tree. Painted from found slides reconfigured in the shapes of rear view mirrors––spare, lifeless scenes in oil and wax that we’ve all glimpsed from a moving car—they reflect on the automobile’s toll on our physical as well as our private mental landscapes. Reyner Banham’s ecologies come to mind. But there’s also something unsettling about roaming the open roads of radical self-realization that someone else has paved. Directly below it, Claudia Parducci’s Trunk (Body) (2021) also examines possibilities for disorder within larger systems. She has filled the trunk with playground sand; buried within it are resin-cast gas masks, shards of breathing tubes, and a single broken laptop. Even the preppers didn’t make it. Entropy ultimately prevailed.

“Disassembly Line” is hardly the first exhibition to engage with the car. Artists (especially in Los Angeles) have been dissecting them, lacquering them, repurposing them and crucifying themselves on them for decades. Nor is it the first group exhibition to play outside of the gallery’s walls (although the fact that the car was shown in the Beverly Hills garage of legendary dealer Molly Barnes, who gave John Baldessari his first solo show, was lost on no one). At times, the seven artworks therein failed to talk to one another, or conceptually meandered away from the theme. Perhaps that was inevitable, as the project’s experimental premise perfectly mirrored the title’s implied social critique. Labor was divided (none of the seven artists were really let in on what the others were up to). Workstreams were individuated (no one could anticipate how the finished product would look). Granting artists this kind of conceptual free rein was a challenge; until the last minute, the curators didn’t know what they’d be getting. “It was tough to write the press release,” Alexander said. “All we knew was that it was going to be a show in a garage with a car.”

-

Michael C. McMillen

L.A. LouverLA-based multimedia artist Michael C. McMillen is known for his immersive, meticulous, set-like installations that make you feel like you’re trespassing on all-too-familiar scenes from the recent past. Life-like props and details, some fabricated and some found––a barrel, a faucet, a septic tank, a ladder to nowhere––prompt you to question who inhabited these spaces, what transpired inside them, and what they tell us about the here-and-now. “A Theory of Smoke” draws upon McMillen’s decades-long interest in architecture and industry to cast light on the provisional nature of permanence so characteristic of Southern California.

It makes sense, then, that the exhibition’s title takes up the metaphor of smoke: ephemeral, ominous, intertwined with disaster. Dangerous but potentially sacred; suffocating but ritually cleansing. Half of a show of illusion intended to embellish, seduce, and deceive. McMillen is onto this: the first work you see upon entering the gallery is a worn, neoclassical-style facade of a 1920s movie palace––Cinema Futura (1990–2021)––shrunk down to the size of a dollhouse. The lone movie poster for Tider Skola Komma (1936), a Swedish translation of H.G. Wells’ dystopian aeronautical future history, Things to Come, essentially speaks for itself. Peer inside and you’ll see footage of a glassy body of water shot with no beginning or end, save for an occasional surfer paddling out on his stomach. Is this the escapist fantasy that lured us out West or a statement about our frailty against the rhythms of time? It’s hard to say, really.

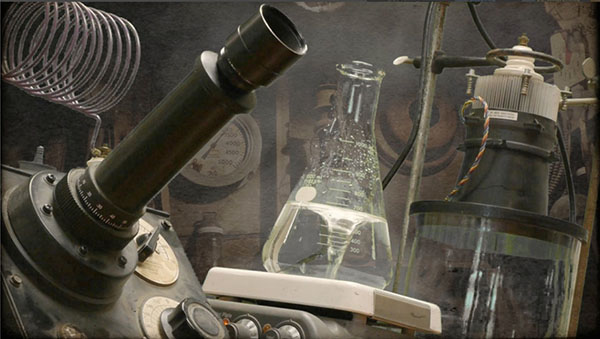

The miniaturized scale of Cinema Futura balloons outwards in Observatory (2021), an immersive video installation occupying one of the gallery’s side chambers. Availing himself of all the tropes of early surrealist film (dream logic, free association, objects that travel and transmogrify from one scene to the next), McMillen presents a convulsive reel of docks, biplanes, beakers and propellers that recall Southern California’s not-so-distant turns as an oilman’s paradise, a manufacturing powerhouse, an industrial port, and the heart of a booming aerospace industry. Large or small, voyeuristic or immersive, the song remains the same, however: both installations remind us that our desire to imagine Los Angeles as the city of tomorrow has outshined the physical debris.

Michael C. McMillen, A Theory of Smoke. still B lab interior, 2010. Courtesy L.A. Louver. The show concludes in a small room upstairs, where McMillen’s sculptures, some now decades old, reiterate his long standing interest in the structural remains of progressive human ambition. Objects like Cistern (2010) and Furnace Cove (2010) betray a puzzling sense of humor; there’s something darkly comic about crafting miniature ruins out of bronze. Others, like Outpost (2015), a miniaturized assemblage of an abandoned factory scaled to the seat of an old wooden chair, recall the expressionist maximalism of Ed Kienholz, albeit with an exacting, declinist twist.

Many of these works have been shown before; that’s kind of the point. “A Theory of Smoke” is as much a statement about our own aging process as those of the material dreams we’ve projected onto the surroundings. Like our most intimate diary entries, the timbre of these works shifts as we see them in new contexts, even as the hands that made them age, weaken and eventually disappear.

-

Intergalactix: against isolation/ contra el aislamiento

Los Angeles Contemporary ExhibitionsStep into “Intergalactix: against isolation/contra el aislamiento” at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE) and the first thing you’ll see is a largish, flattish, squarish stone smack in the middle of a white-walled room decked with wicker beds of tenon sculptures and wisps of fake vegetation. This is Objeto Antiguo, a near-replica of a real Mayan altar stone dating back to 200–900 C.E. The real deal still exists, but it’s far away (in this case, a guy’s backyard in rural Guatemala). That vast distance, between the two stones’ locations as well as the dates of their origins, is precisely curator Daniela Lieja Quintanar’s point.

The past is still with us, the piece suggests. Still active. Still sacred. Still folded into everyday life. Wander over to a stack of printed booklets beside the reception desk, and you can read about Objeto Antiguo in the indigenous Kaqchikel language. You can even cut out a miniature version from the booklet’s pages and assemble it like a paper doll. The DIY context charges Objeto Antiguo as a touchstone of sorts, linking peoples across the slippery, invisible borders dividing the present from the past.

Borders make up the theme of this challenging group exhibition, the product of more than four years of research. Drawing largely from art collectives collaborating across a constellation of disciplines (performance, photography, video, sculpture), “Intergalactix” (the title is lifted from the Zapatista Army’s call for an all-planetary, coalition-building “Encuentro Intergaláctico” or “Intergalactic Gathering” in Chiapas to eradicate neoliberalism in 1996) uses this event as a launchpad to critique the isolation and violence that borders have inflicted on migrants throughout the American continent. Physical borders, conceptual borders, temporal borders; you name it. Borders with a capital “B.”

Crack Rodriguez, Dream Team, 2021: Detail of The Fire Theory installation, Photo by yubo at OfStudio. Courtesy of collaborators and artists. Shifting the exhibition’s conceptual fulcrum to a largely Indigenous experience was intentional for Quintanar: a means of decolonizing her knowledge, she says. Here in Los Angeles, it’s the US-Mexico border that often first comes to mind. This isn’t to diminish its importance to the exhibition. In Metabolizing the Border (2020), Tijuana-raised, Los Angeles-based artist Tanya Aguiñiga dons a Sonoran-hued neoprene bodysuit and armors herself in surreal, anatomically-inspired objects made of hand-blown glass––headgear, footwear, hollow yokes filled with water, a mouthpiece flecked with corroded fragments of the infamous wall––to ceremonially tread the border’s length. The post-apocalyptic camp of her getup calls out the extreme, even extraterrestrial perils that the journey entails.

As you move deeper into the gallery, the borders sink southward, and you start to realize that their impact on the North American diaspora is more complex than the view from 150 miles away. After all, most migrants to the United States have crossed other borders before. At first glance, the varied colors and textures of the soils showcased in Melissa Guevara’s map of the Americas, Testimonies of the paths that marked the flight (2020–21), seems to hammer in the basic point that no two borders are alike. Study it longer, and you notice that the nations that see the most border crossings are artificially swollen in size, subtly distorting the map’s scale.

Nor are all border crossings equal. Moving southwards is much easier than moving northwards, El Salvadoran artist Crack Rodriguez points out in They don’t take my dream (2021), a happening-qua pick-up-soccer game played on the astroturf field in MacArthur Park. That piece of turf, already known for being uneven, isn’t the only way that Rodriguez toys with the game’s rules. One team has seven players. The other has six. One side can score into a standard soccer goal. The other has to make do with a slim opening between the ground and a felled basketball hoop. In Dream Team (2021), the accompanying installation, Rodriguez displays both goals, netted with hand-hewn webs of twine and feathers, as a caustic reminder that “shooting a dream” has slimmer chances of success when shooting in a northern direction.

“Intergalactix” delights in this kind of highly collaborative, multi-disciplinary, boundary-pushing social commentary, a curatorial outlook that’s very much in LACE’s wheelhouse. Yet Quintanar pays homage to the gallery’s history in more ways than one. The exhibition terminates in the so-called Intergalactix Station, where a display of slides and photographs link the exhibition to antecedents in the gallery’s past. You can learn about an interdisciplinary performance about undocumented migrations to Los Angeles organized in 1991. You can also learn about a multimedia labyrinth depicting life in war-torn El Salvador staged in 1981. You may end up leaving “Intergalactix” with a fleeting realization similar to the one you had when you first saw that Mayan altar stone: a glimpse of peoples from all time periods, around the world, who’ve likely never met, yet are fighting for the same things.

-

David Hicks

Diane Rosenstein GalleryCentral Valley ceramicist David Hicks doesn’t have a big footprint in Los Angeles. To see his work, you have to drive out to a hospital in Sylmar: a sun-parched, semi-rustic neighborhood at the northernmost tip of Los Angeles. There, above the lobby welcome desk, once stretched a multitudinous terra cotta thicket (stubby branches and succulent buds, fiddleheads and pinecones), glazed in a blithe, eye-popping palette and configured on thin metal armatures. Imagined as a beacon for a sterile setting, Hicks’ Construction (Bloom Field) (2016) has since been moved to an adjacent building, crammed with desks and hospital gurneys. Visitors today can only glimpse it through a side window, a gesture, perhaps, to the existential anguish of the present moment.

“Seed,” Hicks’ exhibition of sculpture and drawings at Diane Rosenstein Gallery, is more inward-looking, probing the mimetic properties of organic forms we tend to overlook. Inspired by his drives through Visalia, California (the source of much of our food supply), Hicks turns his observations of large-scale mechanized agriculture into raw, personal reflections on time and sacrifice. This theme suffuses the sumptuous masses that Hicks labels “Offerings”: luxuriant heaps of shoots, tendrils, branches and blossoms piled up to four feet in height and lavished with syrupy glaze. While they are steeped in solemn presence, drawing resemblances to burial mounds, Hicks withholds an explanation. Offerings to whom? For what? Are they signs of thanksgiving or penance?

David Hicks, Clipping (White Bloom) (2020). Photo by Robert Wedemeyer, courtesy Diane Rosenstein Gallery The Offerings’ commanding, maximalist presence throws smaller, sparer forms into relief––Hicks calls them “Clippings”––presented, altar-like, on self-hewn tables throughout the gallery. While each Clipping depicts what its title promises—a pine cone, a bulb, a coil of leaves—they are scaled, glazed and abstracted to a degree that they share morphological likenesses with organs. Clipping (Red Vine) (2017) represents a morass of scandent vegetation at the end of its flower, draped extravagantly over a fossilized branch. Doused in red glaze, which bleeds messily onto the bone-colored surfaces, the vines resemble tangled intestines.

Memento mori come to mind, but not in a traditional sense. Firing clay triggers transformations––it desiccates, it hardens, it becomes impervious to the elements––that mirror the aging process. So too does firing glaze, which often becomes the subject matter. The thick white treacle pooling and dribbling off of a red terracotta dish transforms Clipping (White Bloom) (2020), a simple branch, into a well-worn anointing spoon steeped in ambrosial substance. The crusted pigment on Clipping (Blue Green Clusters) (2020), the result of thick application and multiple firings, armors a vegetal form with calloused rhinoceros skin. These colors and textures are timestamps: diaristic records of hours logged alone in the studio at the expense of other activites. They are reminders of the sacrifices made in exchange for shots at uncovering the essential.