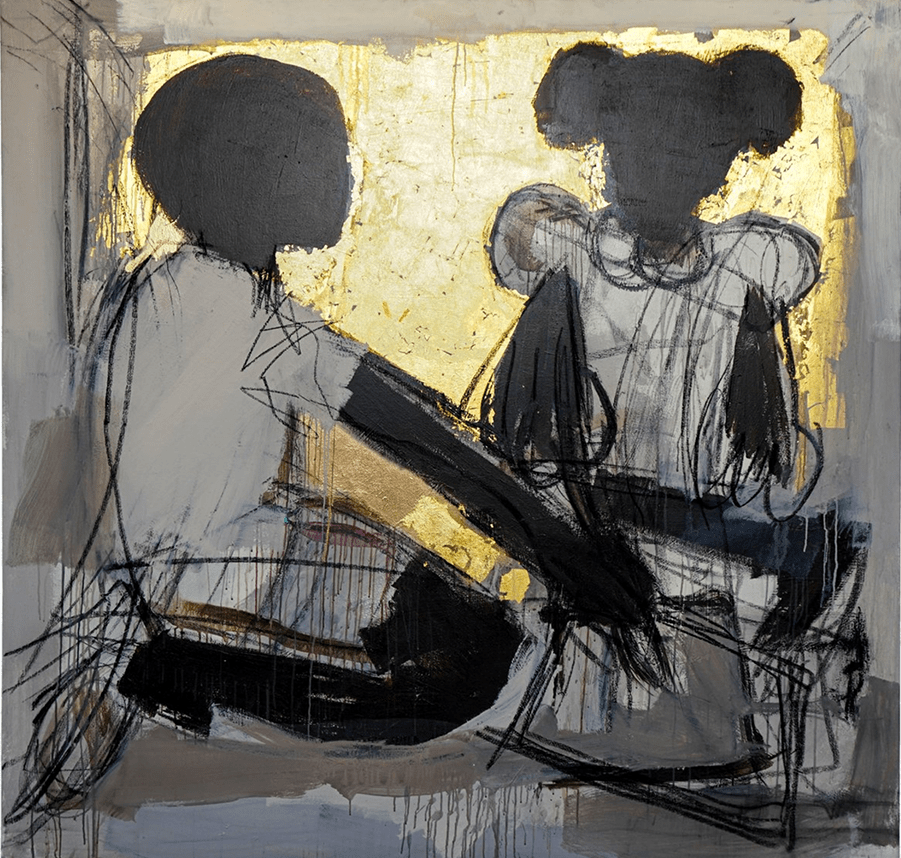

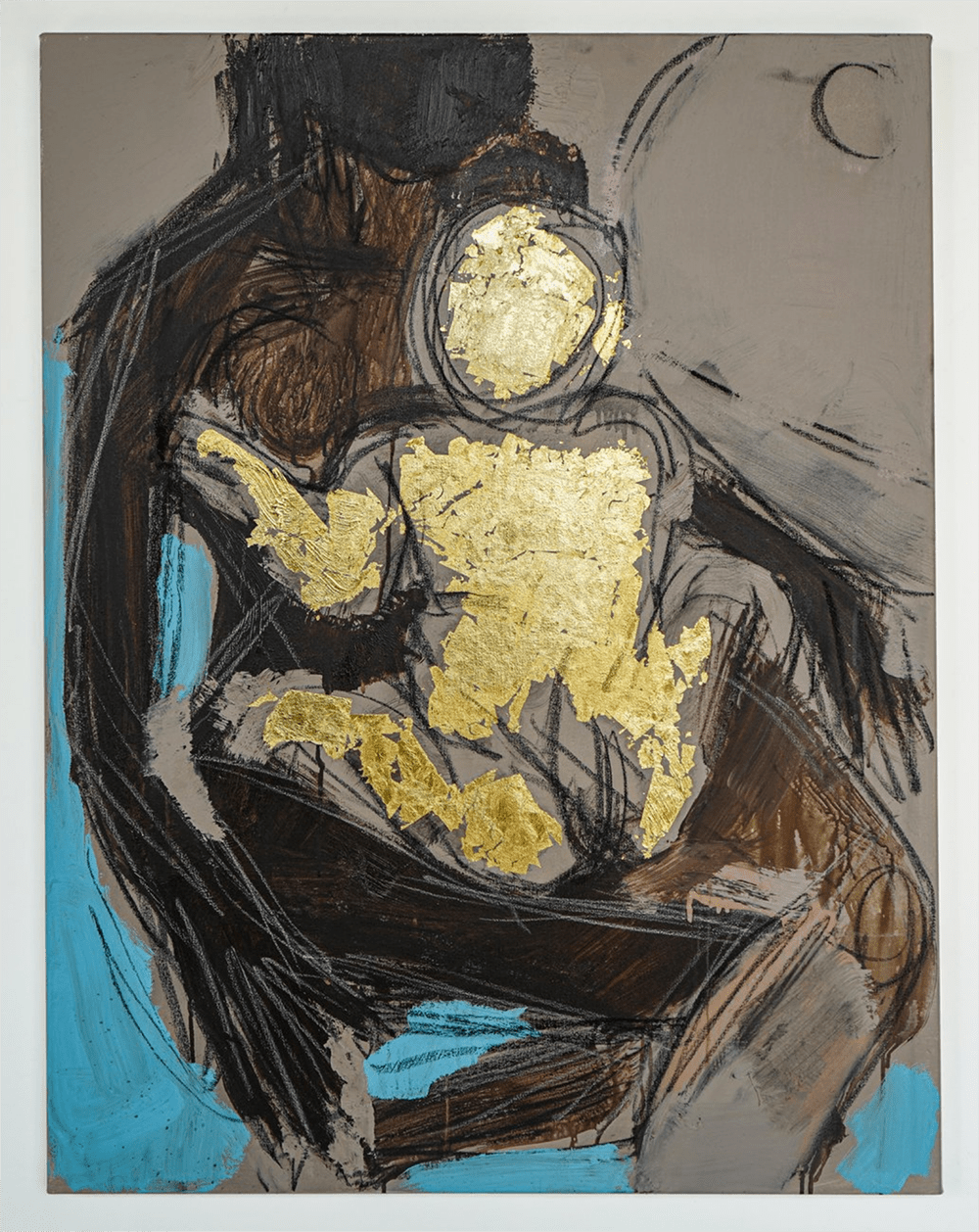

In a suite of charcoal, acrylic and 24K leaf paintings on canvas, Ferrari Sheppard blends compositional citations from the Western art historical canon with an affecting, humanistic narrative of diasporic Black life. Across the mostly large-scale works, Sheppard depicts single or small groups of figures in schematic, pared-down settings—domestic interiors, liminal pastoral landscapes, the sea. With classic motifs like mother and child in Bond (all works 2020), the odalisque in The Moonlight as She Bathes, dancers a la Matisse in Magnetite, he enriches familiar armatures of portraiture and genre painting with a gestural, material and textural depth along with folkloric energy in the style. With wide, rough-edged brushwork and impressionistic faces and anatomy, Sheppard signals the status of his subjects as both living beings and symbolic emblems.

A jaunty portrait called Paka (The Cat) is frank and sketchy and engaging like an Alice Neel. The children in Planes who walk through a field of puffy white flowers (cotton, perhaps) while airplanes circle overhead calls to mind Van Gogh’s The Sower (1889) in setting and pose—as well as Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower in its time-collapsing recombinant storytelling. In fact, the question of which histories are taught—how, and by whom—looms large in Sheppard’s vision, which in itself marries influences from studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and travels on the African continent. In confronting the horrors of the Middle Passage and what came after, he looks for and finds the threads of magic, connectivity and hope that somehow survived.

Ferrari Sheppard, Bond, 2020. Courtesy Wilding Cran Gallery.

The two works set against ocean waves, by making the trauma of the transatlantic journey explicit within the iconography, also have a theater-set quality to them, signaling the performative deliberateness of every choice being made. Despite, or actually, because of the ordinariness of the scenes, the figures being Black does necessary work toward centering people of color within the norms of art history, especially toward correcting the insidious way in which whiteness has been the default for portrait and genre painting, as indeed it has for America’s political and economic systems. Being mostly women and children, the capacity for nurturing, enduring, hoping, protecting and thriving is also foregrounded.

As Kristina Kay Robinson writes in the essay for the show: “What does it mean to love through calamity? To choose love as a method of survival…?” Sheppard’s way of making that explicit in the work is in the pointed additions of gold leaf—sometimes as shimmering highlights, sometimes as scene-stealing radiant color fields. Gold leaf itself is a material in the arts associated with wealth, status and power, as well as religion, enlightenment and saintliness. The remarkable combination of the rough, dark charcoal and the preciousness of the gold leaf is especially effective: this dissonance embodies the themes of both violence and hope that define the history Sheppard both scrutinizes and honors.