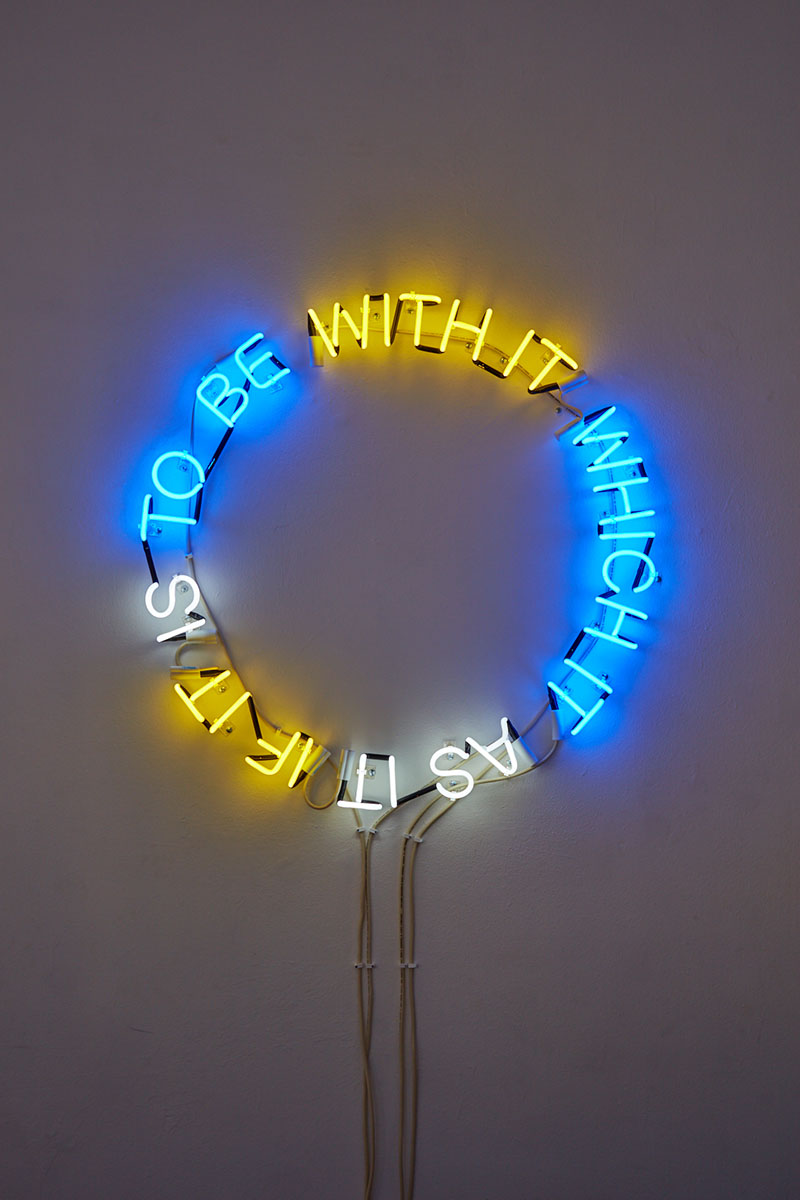

Gertrude Stein wrote in English, but in a way, Eve Fowler is acting as her translator. For the last decade at least, Fowler has been orienting her work across collage, photography, video and text-based practices in response to Stein’s oeuvre. The beguiling aluminum collage-based works, and especially the 2016 video with it which it as it if it is to be that is the centerpiece of the exhibition “Language That Rises,” demonstrate the myriad ways in which her ongoing interdisciplinary exegesis is not only a matter of a literary ancestry with renewed societal saliency, but also an aesthetic expression that in Fowler’s hands is fully translatable from text into the visual.

There are the unique acrylic-print -on-aluminum works, high-polish mirrored surfaces which inescapably reflect the viewer and the setting in a way that both disrupts and completes the lively, optically kinetic composition. For although much of the rhythmic pleasure of Stein’s work is derived from its intonation, she knew she was composing something that was also a visual experience of ink on a page for the reader. Resisting being one is a way of being (2018) has a pointed message to convey; Rose. Rose. Rose Up. Rose. Rose. Rose Up. Rose. Rose Up (2018) has a staccato quality that plays out in both voice and typeface. It enacts twinned references to Stein’s surrealist assertions about leveraging the mind’s library of archetypes, and an honorific lyric for generations of women who counted as feminist activists and heroines.

Notably, the words in the aluminum works are made clipping from issues of Artforum. Part ransom note, part conventional handmade paper collage, conflating medium and message, and also quite beautiful in a densely detailed style, that part of Fowler’s process highlights collage itself as both a studio technique and a state of mind. The 31-minute film at the heart of the exhibition plays on a loop, and in both its use of Stein’s text, read aloud, and in the photomontage editing style of its 16mm black-and-white footage, it too expresses the poetic syncopation of the author’s voice as well as the artist’s affinity for montage as a motif of art and consciousness.

With it which it as it if it is to be depicts 23 artists: women, female-identifying and gender-fluid, each filmed at work or play in their studios, paired with their reading aloud passages from Stein’s “Many Many Women,” a 1910 text that makes an avant-garde accounting of female individuality, self-determination, resistance and solidarity. Its voice is assertively turn-of-the-century, but its spine and its message could scarcely be more current. Thanks in part to the compelling audio, low-key slam poetry of the audio, and largely to intimate yet poetically elusive cinematography by Mariah Garnett, the film, while arguably polemic, is a pleasure to experience as art. This, too, embodies the spirit of Stein, who enacted a bid for total freedom through her actions, aesthetics, assembling of community, and avant-garde life as an exemplar.