No one ever “works” in Eric Rohmer’s movies—but they do read. By necessity, Rohmer’s setting is one of leisure, whether it’s the beaches of Biarritz or the shores of the French Riviera. His characters need ample time to read and to daydream, and for ennui, disturbed by the intruding object of desire, to ripen into an obsessive devotion.

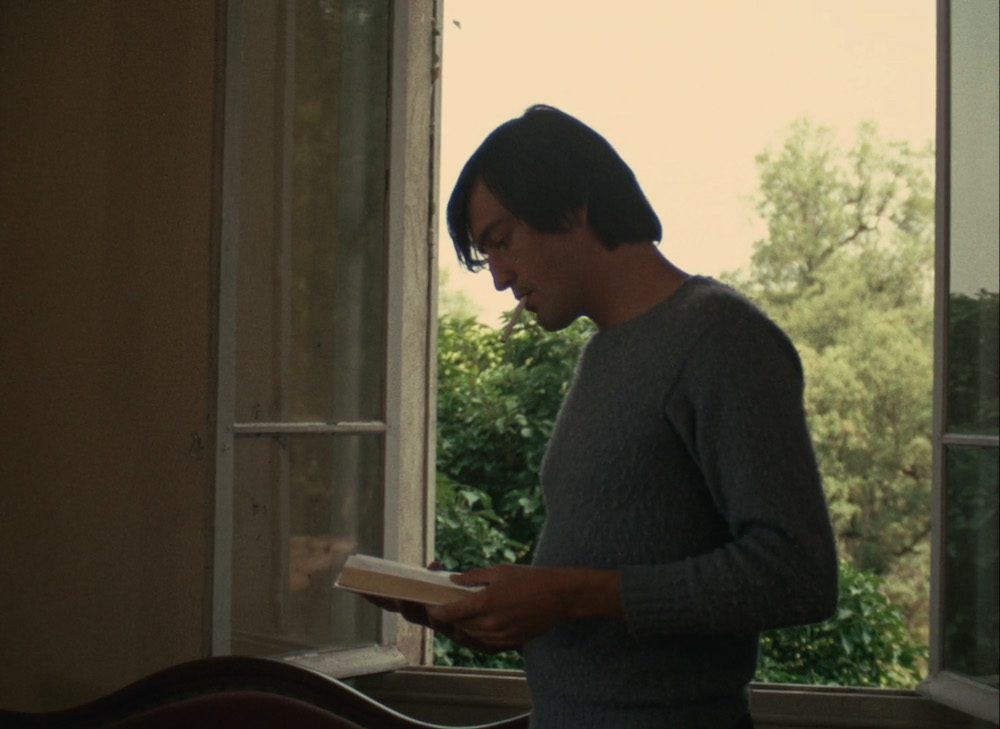

L’amour l’apres-midi (still), 1972

They are not attentive readers. Their attention is elsewhere, with the aforementioned object of desire. They pick up their reading to escape their own feelings, or, just as often, so that they can cruise over the tops of their books. Their conversation is equally evasive. While, as Rohmer has said in a 1971 Film Quarterly interview, his characters “like to bring their motives, the reasons for their actions, into the open, they try to analyze, they are not people who act without thinking about what they are doing…” prolixity makes them expert rationalizers and dissemblers. Books are the perfect accessory for such characters, who in literary conversation can speak of themselves without the stakes of a confession. Only for one moment of exquisite truth do they reveal themselves, every second since the opening credits pushing towards the immense force of will and pressure of circumstance required to make the interior and the exterior meet. Rohmer, the consummate Catholic, makes films about people acting in bad faith.

La collectionneuse (still), 1967

Rohmer began his creative life writing short stories before making a decisive turn towards cinema. In “Celluloid and Marble,” an essay series for the Cahiers du Cinema (1966), Rohmer argues that literature is “a mirror which reflects the world, but which distorts it as well.” It was film that was “the last refuge of poetry” and the only art in which metaphor could arise “naturally and spontaneously.” For example, the lashing copse of trees where the unhappy Delphine finds herself choking back tears in Le Rayon Vert (1986), is not just pathetic fallacy; the trees, the wind, were both real. If literature suffers from a kind of verticality of information, wherein everything comes from the singular voice of the author, the camera allows for the symbolic and the real to exist on the same horizontal plane. Despite the neurotic isolation of his characters, the world is very present in his movies. Les Amours d’Astrée et de Céladon (2007), his final film and the sweetest, might be the windiest movie I’ve ever seen. It is as if he threw all the doors and windows open to invite whatever poetry the breeze might carry. All his movies share the same light, airy simplicity. His longtime cameraman Néstor Almendros described his method thusly: “His criterion is that if the image portrays the characters simply, and as close to real life as possible, they will be interesting.” (“La Collectionneuse: Marking Time” 2006) Hence the willingness to film his protagonists sitting and reading in the first place. Who else has the time?

La collectionneuse (still), 1967

Simone Weil, a fellow Catholic of the modern period, said that beauty is often the first way to God: it is a lesson in his remoteness. Something that is beautiful is whole; it wants nothing from us, and thus is a kind of tease as well as a kind of truth. Rohmer’s readers, likewise, languish in a world of resounding beauty that intensifies their own frustrated desire. In Le Genou de Claire (1970), for instance, protagonist Gerome strolls through an actual rose garden while considering his erotic fixation on the budding teenage sisters Claire and Laura. To the precise degree that Rohmer’s characters attempt to hide their yearning, Rohmer’s camera entraps them in it. Maybe that’s why they are so eager to hide their faces in their books.