Your cart is currently empty!

Decoder

I was, for six or seven seasons, baffled by The Cool Wall.

It’s a wall full of pictures of cars on the British car show Top Gear. They take cars and go “Cool? Not cool? Subzero?” and then put the picture somewhere between left and right, between cool and uncool, with magnets or Velcro.

The thing is: The cars mostly on the show—the ones not in the Cool Wall segment, the ones in the bits of the show where they actually do things with cars like race them against assault helicopters or drive them into laboratories full of ping pong balls—are often very cool: insane Zondas only a single DNA molecule removed from dune buggies and Formula One racers and green Lamborghinis on fire. Yet the cars on the cool part of The Cool Wall are just the same gloss gray soap lozenges you see larding up parking spots in West Hollywood every day.

Clearly, the middle-aged men who present and produce Top Gear are able to detect all that is good and mad and wild, but were still insisting on visual mediocrity and the aesthetic of the muddled middle.

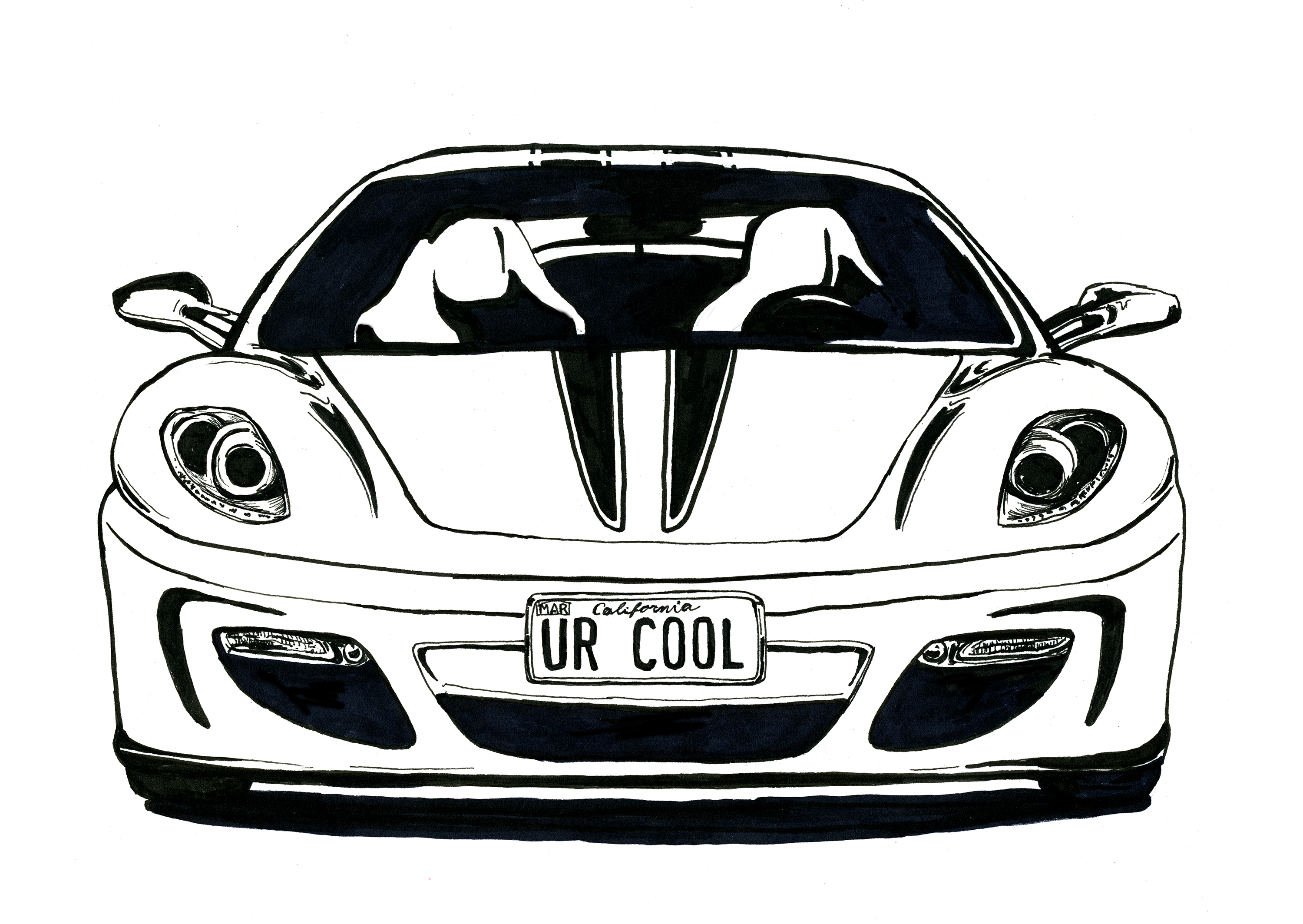

But somewhere in Season 8 I figured it out: The Cool Wall isn’t about the car at all. It’s about how much like a sore thumb shoved through a wedge of cheddar your presumably bald and presumably British head will look behind the windshield of a roofless lemon-yellow Porsche. It isn’t that the Porsche is bad, it’s that it makes you look bad. The Porsche makes promises about speed and excitement that an audience of strangers—with only that car and your baldness to go on—may suspect you can’t keep.

Now on the other hand we have this stately upright steel brick with the complex grillwork over on the far end of The Cool Wall. That says, “I’m sophisticated and rich and you will be comfortable when you are with me”—an assertion which nothing about your thinning hair directly contradicts. Buy the Audi.

The car is here not as a moving sculpture but a fashion accessory—and not like a fashion accessory for a fashion model or anyone fuckable, really—more like a brooch the Secretary of Health and Human Services might wear on TV. An accessory not meant to affect the way you look but meant to subconsciously insert useful ideas about your aspirations and skill set into the observer’s head.

Or, more simply: It’s marketing. Marketing selves to other selves.

And, yeah, these same self-conscious drivers sometimes have walls and art collections and have their full names attached to things and may, on occasion, have personal or psychological reasons to be more interested in what their collection tells people about them than about what it has to offer them when they are alone in a room and it’s sitting there staring back at them under the track lights. And even deep into an honest, quiet moment alone with a picture or film or thing, sooner or later a thing asks us not just to consider it, but how it sits next to us.

Bold, aggressive, new, visceral and, especially, young art seems to make demands on a viewer—and on the world: Things don’t have to be the way they are now! Go! Do things! The world is large and not yet explored! But then, for the collecting classes, there’s always a spouse and a kid and an obligation and a kidney to worry about… the world does have to be the way it is now, there are only so many places to go and only so many things that can be done. Much of the art that, in a less self-conscious world, would be heralded as fascinating and powerful will feel, to these people, at best unrelatable and, at worst, out of touch with reality.

Many artists have given in and now pitch their work right down that center: enough fantasy that folks will want to believe it, but enough reality that, for a second, they can. Never mind that there might be better uses for museum walls than sanctifying the validity of what you’re already doing and turning the art experience into a long and suasive gurgle of free-flowing psychotherapy; a lot of people need psychotherapy, and will take it where they can get it. You’re okay. You’re okay. It’s tough to be you, but you couldn’t be any better. You’re cool. You’re cool….

This column was originally published in the March/April 2013, vol 7, issue 4 of Artillery