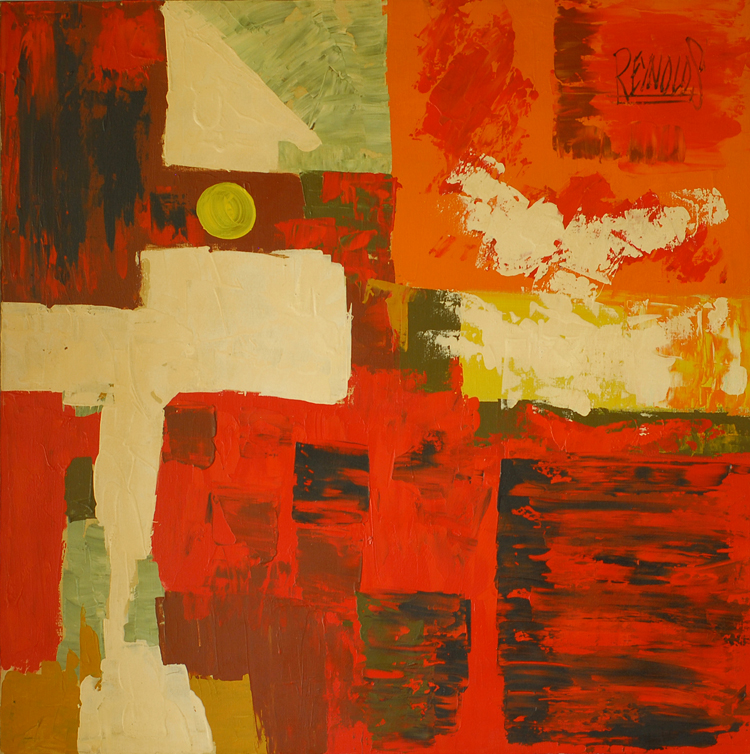

Ten years ago, I was driving down Venice Boulevard one morning, late to work as usual, when I spotted a large modern artwork among the bric-a-brac in front of a thrift store. It’s got to be a poster, I thought as I circled the block. But no, it was a framed abstract oil painting with an over-sized, stylized signature in the upper right corner that said REYNOLDS. Being a fan of art featuring typography, I paid $15 and soon the canvas was hanging on my bedroom wall. Internet searches over the years led nowhere, but I suspected it was an early ’70s-era painting mass-produced in Mexico for tourist consumption.

Recently, my friends who own a vintage furniture shop showed me their collection of Reynolds paintings, including one that looked almost exactly like my beloved abstract (but arguably, not as good). They didn’t have any information about the artist, either. Coincidentally, last year I picked up a giant, lurid painting of sunflowers signed “Lee Reynolds” at my neighbor’s yard sale for $5. With my curiosity piqued anew, I found tons of Lee Reynolds’ original oil paintings in many different styles and subjects on eBay. Who was this often kitschy, sometimes brilliant, and very prolific artist? A Google search finally hit pay dirt.

In the late 1960s, Andy Warhol had glamorous lackeys silkscreen his canvases for him and called his studio The Factory. In the art-boom ’80s, Mark Kostabi set up an art sweatshop where struggling East Village painters made Kostabi-esque works under his not-so-watchful eye. But in 1965, Lee Reynolds Burr and his Vanguard Studios were there first. His original “art factory” in Beverly Hills produced more painted canvases bearing one signature than any artist in history, but none of the artworks for sale were actually painted by him.

Burr was born in Los Angeles and graduated with a BFA from UCLA in 1962. He initially created artwork for Bertini Studios but soon decided to go out on his own. Two years later, he founded Vanguard Studios with his business-savvy brother Stuart to give average American families the chance to own a “real” oil painting, much like the etchings that had democratized the art-owning experience in America a century earlier. With paintings sold through a network of Vanguard showrooms, furniture stores and interior decorators around the country, business started booming, and 10 years later, both men were multimillionaires with a publicly traded company.

Burr never set out to be part of the contemporary fine art movement. His product was decorative art: pieces that would look nice over couches in middle-class homes, with an actual artist’s signature (usually “Lee Reynolds” or simply “Reynolds”) to make them seem more exclusive and genuine. Vanguard tackled many different styles and subjects—landscapes, bullfighters, supercute or sad children, boats at sea, flowers, architecture, still lifes, romantic images of old Europe, and more—very well, with the representative pieces often mirroring the illustrative style of the day. Burr painted original works that were then copied by his crew of artists, but as business grew, he hired Americana painter Harry Wysocki as Vanguard’s chief designer and employed Argentine artist Aldo Luongo to contribute designs. Burr periodically traveled to Europe (where he hung out with Salvador Dali) to buy paintings at auctions that he could then replicate at his LA studio for mass consumption.

At any one time, Burr had between eight and 20 artists working at Vanguard, copying paintings by Wysocki, Luongo or himself—works that became officially known as “original reproductions by Vanguard Studios.” The young artists were paid by the painting and often churned out ten 48” x 60” canvases a day, sometimes with wildly different interpretations of the master designs. Most bore the name “Lee Reynolds,” but specific accounts, such as furniture stores, wanted exclusive artists’ signatures, so “Vanguard” morphed into the Dutch master-ish “Van Gaard,” and the fictional “Stuart” signature was a tribute to Burr’s brother.

Dismayed by his artists’ inconsistencies, Burr created a new assembly line system: Each canvas would be hand-painted with a two-color background, then, the black lines of the master design would be silk-screened onto the canvas, followed by more hand- painting done by the production artists. (The number written on the back of the canvases referred to the painting master, while the initials belonged to the studio artist.) All the master paintings were eventually destroyed systematically.

Burr’s nephew Christopher recently created a Web site to set the record straight about his uncle’s work, but unfortunately, the site is now down. He invited owners of paintings, prints and wall sculptures signed by “Reynolds,” “Lee Reynolds,” “Lee Burr,” “Van Gaard,” “Stuart,” or “Burton” to submit photos and stories about where and how they acquired the artwork, in exchange for background information about the collectible, which he then posted for all to see. His site featured hundreds of works and got more than 30,000 hits a month, and the emotional attachment people revealed about their paintings made it clear that these artworks were an important part of their lives. One collector noted that his horseracing-themed Lee Reynolds painting was featured in an interior on TV’s I Dream of Jeannie. Burr himself often commented on the displayed works, and it was easy to read between the lines about what he remembered fondly and what made him wince. While it’s estimated there were more than half a million Lee Reynolds paintings created, Burr has only painted around 350 original canvases of his own in his lifetime with precious few, if any, ever available for sale by Vanguard.

Burr sold his interest in Vanguard in 1974 and worked as a consultant for them until 1979. The company continued on without him under many different owners until it faded away in the late ’90s. Burr started East Park Gallery in New York City in 1983 and for 10 years it produced works of art to serve the higher-end markets of interior designers and luxury hotels. Well known and well regarded in his hometown and in art circles, Burr was commissioned to paint a 21-foot-long triptych to commemorate the 1984 LA Olympics that hung at the International Terminal at LAX for 20 years.

An avid art collector himself with Picassos and Renoirs in his collection, Lee Reynolds Burr is still a dashing figure who wears his ascot very well. He paints in his desert studio in Indian Wells, CA, where he recently completed his first commission in 20 years, and also spends time in LA. These days, he’s painting originals: wonderfully rendered ballerinas and color field collages using gold leaf and compositions with architectural motifs.

This article originally appeared in our November 2009, vol. 4, issue 2

Lee, I have happy memories of being connected to your East Park Gallery. I would love to be in touch. Do you have any old catalogs available? Thanks, Nick Cann

Thank you for this article. I’ve been trying to find information on lee Reynolds for years. I have an amazing painting by him and just wanted information about him. Thank you again!!

I have a paiting signed “Stuart” and has the Vanguard labels on the back along with “Lot 194”.

Can anyone tell me about this painting?

I have a large Lee Reynolds oil mostly in black & white of a lighthouse on a bluff in stormy weather. Signed Reynolds. Would love to know all about it.

I have a Lee Reynolds painting on canvas in browns/pinks. Looks almost southwestern. Numbers on back 132812 and then 18010722-9. Like to know about it and approx worth? Thank you

i have a large abstract oil painting of musical instruments signed Lee Reynolds and the number 132283 is on back. Where could I find any information regarding this painting? .gary pillet basto

I have a very large Oil painting of two giraffe’s … very close and sharp.. very majestic.. The number’s on the back of painting are 132207 on the cross bars.. 001-00654 are along the bottom.. and in red off to the side is 91-T2-12

Any info on this painting is greatly appreciated.

I have a large textured oil painting signed lee reynolds with number 153923 on back. Would love information on this particular painting. Thank you

I have a large painting of a lady all black and white in a cafe the window in the picture says “la cafe” the only color in the painting is her red lips and a red handkerchief. signed ‘Lee Reynolds’

I would love to know some backround information on it if anyone knows.

thanks!

Hello, a correction to the original article above: Burr graduated from USC, not UCLA. For everyone inquiring about their Lee Reynolds paintings and their worth, it is all driven by the market. It seems like the abstracts go for more on ebay than the figurative stuff. There is no real art world collector market for works from Vanguard Studios although some exceptional pieces have sold in the low thousands. Remember that Lee Raymond Burr didn’t actually paint the canvases but he did run the studio where they were created. It is very difficult to know the year your painting was created or how many similar themed canvases are out there since records weren’t kept and the info sharing website has been pulled down. My advice: enjoy your painting or sell it on ebay but don’t expect to get rich on it.

Thank you for the great, very informative article Frank! I wish there was excellent information on more artists & artist studios like this online. Much appreciated!

Would like to purchase the large[40″x 40″] painting by Reynolds, of a large butterfly from a few years ago. Can you tell me where and how and how much?

Hi. After reading many comments on Lee Reynlolds I came across yours. Although it’s been mine for 20 plus yrs now, your asking about a large butterfly made me reach out. Mine is titled “Asian Monarch” mostly gold in colour except the butterfly being in grays, white details etc. oil on canvas signed – Lee Reynolds.

I bought a huge canvas painting of Flowers in a Vase years ago in Las Vegas ; every house guest loves it!

I too have a Lee Reynolds painting a vase with flowers. I have pictures

We have a painting of Lee Reynolds with a certificate. Does somebody know where we can find out what the value is of this painting? How old it is and more information. Thanks.

I recently purchased a Lee Reynold painting of a Covered Bridge number on it are 142516 with a stamp reading VanGuard Studios inc Copyright Pending also has 91-sz. any information would be appreciated

I have a massive lee Reynolds with a lady on a balcony. Very Paris or San Fran looking. Would love to know any history.

I think I have the same one, are there towels hanging on a clothes line?

I have likewise purchased a Lee Burr at an auction it was a beautiful white background with ships as the subject at a pier Is there a way to convey a message to Lee?

I have a lee Reynolds painting 41×41 with the initials T.D and no. 583 from van guard studios Beverly hills calf.. I don’t know much about it other than that its oil on canvas. maybe you can help

I have a large Lee Reynolds / Vangaurd Studios of a cityscape busy cross-street rainy with a bus # 153904 on back .. just wondering what it might be worth , someone was interested in buying it ..

Thanks

i have a large Lee Reynolds ! contact me

Please let me know what it looks like and if it’s for sale what’s the best you can do for it if I’m interested in buying it?

I also have a very large canvas signed lee reynolds is from Vanguard studios measures 40×59 and is pastel colors of a city skyline. Very abstract and beautiful MINT condition. Make me an offer if you are interested.

HAVE LARGE PAINTING OF HORSES LAYERED IN ORIENTAL STYLE SIGNED LEE REYNOLDS LOWER LEFT. NO VISIBLE MARKINGS OR NUMBERS ON BACK OF CANVAS. ORIGINAL REYNOLDS OR VANGUARD?

I have two Lee Reynolds paintings, one is a cowboy on a horse and the other an indian on a horse, they make a beautiful pair, they are huge, have had them for many years, always wondered about the author. Thank you for this informative article, very interesting indeed.

sorry correction, large canvas layered in horses oriental style signed lee Reynolds, lower RIGHT SIDE (my other left!!). no other visible markings on canvas back etc. any history available??

I have a floral painting

I found one of his paintings in southern Indiana back in 2007. I love it! 3 large white flowers with a textured gold finish tip. It has to be 3.5 ft x 3.5 ft. Of course my college roommates were like “okay grandma” pssh I love the painting and the frame! One of my greater finds at Backstreet Missions (similar to good will but I think the $ went to our local homeless shelter).

I have a large abstract piece by Lee Reynolds # 153830. It measures 60 X 48 with a frame in excellent condition.

I have a 60″X48″ Lee Reynolds Painting that was originally purchased as a one of a kind from an Oregon Furniture store for $350.00 it is a LightHouse on a Stormy Sea backdrop with lots of swirling yellows and orange shades with sea gulls flying. We have owned it almost 40 years.

I’d like to sell it if I could get a value. The numbers on the back are 646 LS.

Clark

I too have the same painting of a lighthouse on a stormy Sea with swirling yellowish,reddish, greenish,brownish, black sea gulls the lighthouse sit off on rocks with brown, black greenish coloring. On the back of my painting it states 646 PS and a price of $160.10. It has another $ amount also on it.

I received my painting as a gift from a friend who did not want it because it was so large (4×5)

I have spoken and written to both Lee Reynolds family(spoke with Chris) and also (Vanessa-I think is her name) of Aldo Lungo family in reference the painting. I also had my son to show the painting to an art gallery in California about a year ago and they thought it looked very familiar with Aldo’s painting.

Anyway I too would love to sell my painting.

I have that one too

I have the same one. Mine has no numbers on the back.

I have one Reynolds that is very similar to the first shown.

I have a large oil abstract on canvass 5× 4

Signed Lee Burr 88

Cant find anything out about it. Have paid to different internet fine art appraisal sites and both times got my money refunded due to lack of info. Could this be one of the very few original ones??

I think I have the same light house painting as Gail Powell. Bought it in about 1970 for about $100

133187 with THE VANGUARD CIRCLE on the back of the Painting I have some VERY exspensive art in my home, but my Lee REYNOLDS Painting gets more attention then almost any of my art. I have never seen one like it.It is 4ft x 5ft.a COUTRY SETTING like an AMMISH CITY with HORSE and Carriage and an OLD IRON Wheel Horse Bugey, withTWO WOMAN walking to Church. I have seen hundreds of LEE REYNOLDS PAINTINGS but non can compair to yhis. I am 69 and have owned this since 1983. Anyone interested in seeing it, I would be more then happy to send you a picture.

What’s it look like and is it for sale my friend??? I discovered this unique artwork 3years ago and am always intrigued by it…this description you gave of this painting is one I haven’t seen and would love to see a pic of it if you wouldn’t mind?

I used to work at Vanguard studios in the late 70s I enjoyed working there because of all of the various personalities and friends that I made most of them were quite crazy it was a very interesting place to work we used to work with 15 to 20 canvas is a day painting all the same scenes and signing them all with the same signature Lee ReynoldsI often going to peoples homes and see paintings of perhaps ones that I did when I worked at Vanguard studios it’s amazing how people think that they are original paintings and they’re not mass produced by artist like me we got paid by piece work and sometimes the conditions in the studio very harsh it was either too cold or too hot but it any rate it was a good job

It is nice that you wrote to share that you were one of the persons who contributed to many fine paintings. I love my painting, no matter who put a brush stroke on it. It is two large pink flowers, white tips, and green leaves and grayish background. Just love it. size 48 x 48, on canvas, and a gold frame. I don’t recall any numbers on the back, and it is too large for one person to take down to check this out, but it is signed Lee Reynolds. What a smart businessman he is, to make so much money in art works. The paintings sold at modest prices in the furniture stores, where I purchased mine in Vancouver, BC.

I just bought a beautiful picture sign Lee Reynolds and has a tag on the back from Vanguard Studio and a picture and writing of Lee, The picture is on a canvas maybe 48 by 60 and has 2 vases one big and one small there white and black with a design on them one has cat tails in it other some kind of brown leaves or flowers .It is a still picture has a number on each side back of canvas 3242 .I call a studio in CA they told me to take a picture of it and email it to the Director he might be interesting in it. She also told me that his pictures start off at couple thousand dollars. Can you please give me some information on this and what they number on back means, Thank you for you help have a bless day.

Hi Mary, did you by chance paint any waterm lillies? Approx 40×50″? I was unable to attach photo.

Hi, whyle reading the story about Lee Reynolds i see all his signatures “Reynolds,” “Lee Reynolds,” “Lee Burr,” “Van Gaard,” “Stuart,” or “Burton” but what about this signature “Leerey Nolds” this signature i have on my oil paint, is this also a Lee Reynolds signature?

Have a Lee Reynold’s painting. Abandoned farm house or such with wagonwheel in front snow on ground. Need info.

Thank you for the article. It is very helpful. I love my LEE REYNOLDS art. It is appx. 24×30″. It is mainly pink,mint,coral, and blue colors. It is a scene of mountains,trees,sky and water! It is gorgeous.:-)

Does any one else have one like this?

It is signed Lee Reynolds on the lower right side. I am extra curious about Lee because my name is Reynolds as well. 🙂

I have one like that but one also has a bridge.

I own a beautiful 60×48 gigantic tree in mostly shades of browns/gold… framed in dark brown wood…has a small stream in bottom right corner…signed Lee Reynolds left hand bottom…I have a small ranch home and it covers too much of the wall above my sofa…and makes other décor dwarf in size…so it is now in my spare bedroom..The number on back is 3363…My heart is broken that I have no where to hang it..Does anyone have one like this or know anything about it? Thank You in advance.

I went to EBay and found the painting..called Tree Mid Century…asking $2,999 plus $150 shipping..most expensive of 170 others listed.

Hello Lee,

My friend has a piece of artwork of yours and is hoping you can provide some background information, as well as the value of said piece.

It still has it’s tag: “OTHER ONE” – original paper sculpture

She acquired it by working for a lady who could no longer pay for her services and instead was given this piece of art in lieu of payment.

Hi we recently purchased a painting at an auction called “sunset flight” with Lee Reynolds in the left bottom hand corner. It also has vanguard studios original tags on it. Can’t seem to find anything on it. Any information would be great.

i just bought a van garrd its green background with 3 horeses the horses are in blackwith gold painting (strapsan stuff) of a horses gaer..got for 24.00 bucks its very beautiful for its retro 70’s look the frame is like the others of horses paintings ive seen of the work done from this company please tell me more!!! cant waite…:)

My father recently passed away and left me with this very large 51″ x 41″ painting of ships at harbor. Unlike any I have found this picture is signed in the top right corner and just says Reynolds. It has a number on back….536 in black permanent marker and again 536 in pencil with initials next to it. I am assuming that the initials are from one of the hired painters……but I have been told that when an artist left a picture unfinished that sometimes Reynolds himself would finish it and sign his name “Reynolds” in the top right corner I can send a picture to anyone who may know anything about it or is interested.

I have a textured, signed by Lee Reynolds,on canvas, framed # 153471 of a rooftop view of twin towers andstatue of liberty. How can I find approx. Value?

How can i tell if i have a original Painting from Lee Reynolds? Thank you

I have one #133089, paid $5 for it at a rummage sale at our church this past Saturday It’s signed Lee Reynolds.I love it, even if it’s not an original.

50×40 on canvas,with gold metal frame. Flowers of pink and white and bluish color in a square vase. Is it an original?

I have a very large Lee Reynolds oil painting of a lions head. It has the number 527-LW on back and the tag is there also telling about the Van Guard studios and about Lee Reynolds Burr. My painting has Reynolds on the lower right hand side. Would love info about this painting.

i have a lee reynolds of the hummingbird and wanted to know where to find out the value of it. could you help?

I am in possession of a 5 foot x 4 foot oil on canvass, signed LEE REYNOLDS

4 children, I see them as resembling the Beatles. Neutral tone background, darker tones and black haired subjects. Owned this for 20 years, unsure of its origin. Would love to post some pictures as any information would be greatly appreciated. Email me crichardson24@cogeco.ca

I have a pair of table lamps that I obtained after my parents died. I was about to spray paint them when I noticed the signature Lee Reynolds on the base. The signature matches the signature I have seen on paintings on line. Anyone know anything about him producing items other than paintings? Thanks!

My Lee Reynolds painting is a small “white tree” forest with stream running through the middle of it. Only mark on back…. #132365… It’s a beautiful piece.

I have #2247 painting with the signature “Reynolds”. It is a floral painting with cream and blue flowers set on a background of browns, gold, and cream colors. I am looking to sell it.

I have a painting on wood by him. An old lady at a church told me before I bought it that her husband bought it for her over 40 year’s ago for her anniversery. She said it was worth a lot of money and said for me to take good care of it. When I saw it and picked it up that I was the only person that took interest in it. She knew I fell in love with it, she knew I was happy to have came acrossed it. It’s yellow back ground with a fountain and a couple standing next to it. It is abstract and she said it was called “the fountain”

Again about “the fountain” I am in the mood of selling this piece anyone interested in it please email me. It’s a beautiful painting and when I bought it, it was around the year 2000. So over 40 year’s ago to that date is when she said it was bought. I’ve had it for about 15 year’s since then. duelingchad@gmail.com.

I am an artist and someone gave me a Lee Reynolds painting so I could use the canvas to paint on. After looking him up online I think I will simply use the canvas because it seems they are mass produced nothings. I have to say he is more of a business man than he is an artist. He’s rich and Im a starving artist. GOOO LEEE!!!

I have a 60 x 48 beautiful in perfect condition oil painting entitled “Springtime” . Signed in the lower left corner by. Lee Reynolds. In the original frame and still has the art sale tag on back. Anyone interested in buying this piece can contact me at stevereagon33@gmail.com. Pictures are available upon request. Buyer inspection welcomed.

Hi I have a 24×48 landscape oil canvas painting it’s got ships in the sea over looking some kind of city it’s signed Stuart with #288 and stamped on the frame says Vanguard Studios 1967! If anybody has any infor would be greatly appreciated! I cant find anything on it! TIA

I inherited a large LEE REYNOLDS painting from my mother-in-law. It’s a Seaside scene showing an old pier in the misty distance, seagulls flying in the foreground along with more dock-like structure/rigging. The colors are muted grays, brown, sea-green, with touches of yellow and white. There’s a handwritten number on the back if the canvas which is 674. I would be interested in selling but have no idea it’s worth.

I have 2 oil paintings on canvas both sign “Reynolds”

I have a Lee Burr ’86. It is a 3 dimensional piece on plexiglass. I obtained it in an auction. I would love more info or a buyer.

I have the Lee Reynolds Yacht Race, I did not think much about it until I recognized the brush strokes in someones home and decided to run a search coming across this site. The only thing I have changed with it is the color of the frame, I had it painted to a hammered bronze look. Love it! MarZia

Hello i recently found a lee reynolds canvas really large it was in an old remax reality building in greenwood indiana. With the painting there was a proclamation stating that in i think the date was 2002 was the most profittable remax in the country that year. I kept the painting however the proclamation some how was lost. Just curious if any one would have any information on this if it were done by a student or lee himself. It is of course of hot air ballons !

I have a large one also but it is signed Lee Reynalds or so it looks like an A. Would this be one of his???

I just now looked at back of frame and it from Vanguard Studios imprinted all around the inside of metal

I have a lee reynolds canvas with flowers on gold background with bamboo like frame. I’ve tried to research it but hadn’t seen nothing similar so far. #2595 ck is on back. Can anyone help?

I have a Lee Reynolds 5 x5 ft canvas that is 3d it is so unusual. It has paper and rope and raffia. I would like a value on it. It’s all white.

I have a Lee Burr painting the name is in the night. I would like a value on it. Thank

I have a reynolds painting series #132290 2 wood dicks old barn door background what is it worth?

Just purchased two large Lee Reynolds Floral Scenes Textured Oil on canvas paintings. Both are super-clean, one is signed, other has Vanguard Gallery tag attached to back. Both have numbers on back.

I have a painting signed by Lee Reynolds an was trying to find out if it was real it’s oil and of white flowers I wish I could post a picture of it. Besides being beautiful I was wondering if it was worth anything?

I have inherited my uncle’s 48 x 60 (i.e. 60 wide)Lee Reynolds mid-century abstract #153465. My uncle originally bought it at a department store in Boston before moving back to Hollywood with it more than twenty years ago.It is composed of overlapping rectangular shapes in various subdued shapes of ivory. blue,. red and browns./

Have a desert landscape signed lee Reynolds 108303 40×80

Hi I have a signed Lee Reynolds canvas oil painting of the wrights brothers biplane on a ledge it is a 3 foot by 4 foot painting.how do I get it appraised to see what it is worth?

I have owned a painting signed van gaard Numerous ships skeletons. Bluish black background. The ships are raised with a glue like substance. I am very interested in finding out more information on this piece. Thank you in advance.

HI MR.REYNOLDS – I HAVE A PAINTING THAT WAS GIVEN TO ME BY AN ASIAN MAN WHOSE WIFE DIED LEAVING HIM YOUR PAINTING…IT IS A 48X60 AND WAY TOO BIG (ALTHOUGH BEAUTIFUL AS IT IS) FOR MY TINY HOUSE. THE NUMBER ON THE BACK IS 158824 IF THAT IDENTIFIES THE PAINTING FOR YOU. I WOULD LIKE TO SELL IT BACK TO YOU IF YOU

ARE INTERESTED SO SOMEONE WHOSE HOUSE WOULD BE BLESSED BY YOUR PAINTING COULD BUY IT. IT NEEDS TO BE IN THE HOME OF SOMEONE TO BE APPRECIATED.

I live in uk and have a large lee renolds painting in pink blue and green. It reminds me of de waldens pond. It has a bridge over water with water lilies and weeping willow trees. I have had it for 30 years. I know nothing about it. I just loved it when i bought it. I dont plan to replace it.!!

] just bought a lee reynolds large frame picture # 3383 painted

[ have another it is worth 1600 same [print but the one i have has color

I have a Lee Reynolds oil daisies in soft tones of green and white and a Reynolds oil of flowers/ blues greens with hint of red, look like Shasta daisys. Just trying to access values, one received from moms estate and 2nd from a second hand store.

I purchased a gigantic abstract painting 68″ by 88″ that is signed Lee Burr ’83 at a consignment store in Naples, FL. It has four stamps on the back, 2 for East Park Gallery Services and and 2 for Lee Burr New York USA. It is a heavily textured abstract painting of horizontal stripes in pink, yellow, green, white and brown on a light to medium gray background. I would appreciate any information available on the painting, It is a beautiful painting but sadly it is not going to work for me in the new home I am building due to its size.

I picked up a two piecer at Goodwill, one signed Lee Reynolds and the other the obvious match. It looks like it’s straight out of Miami Vice! Brilliant!

I inherited a large oil painting signed Reynolds in the lower right hand corner. It is a field of blue and cream colored flowers with brown and gold tones in the background. I have not seen any images of Lee Reynolds work that matches this so curious if it is an original or not. The gentleman who gave it to me attended USC during the time Reynolds did and I am curious if they may have known each other. This man had other Reynolds pieces as well. Trying to determine the value.

I have a Lee Reynolds for sale on eBay right now. 9/19/2016. It is of the Wharf with 2 boats & buildings in the background. It is In shades of green; teal, turquoise, sea foam with yellow & white accents. I have it for sale at $900 which includes us shipping. Shipping alone will cost $150+

Have a look. It is perfect!

Thank you Frank. Great article.

Elle

I have a large signed Reynolds oil painting on canvas w/wooden frame. I received it as a gift from another artist just before her passing. I cannot find another picture of it anywhere. It is bright yellow with whites, creams and browns. Maybe it is a lighthouse, but that one has seagulls… This one does not. The # is 590 (on the back of the canvas) and the frame has the #13 and another sequence of #’s 23-1 L590-0006

Hello Cathy! I just bought a “Reynolds” today

At a garage sale. Lots of Browns some color

In the branches. Does this sound like yours?

Laurie in Cincinnati!

Forgot to mention it is a hummingbird on a

Branch.

I have a large abstract western painting signed Lee Reynolds of a cowboy on a bucking horse. Love it! Googled his work and unble to find it anywhere or the name of it? Any help? Curious! lisalynnpage@gmail.com

I have a large 48 x 60 painting with signature on the lower right corner and number (637R) on the back. It is the picture of 3 wooden sail boats on the water. We purchased it in a moving sale in 1980.. Any. Idea how much it’s worth .?

Irrmember going to LACC with Lee in the early to mid ’60. It was a good time. Lee was always trying to get jobs working as an extra in the movies. I believe his heart was always to be an artist. I would love to reconnect with Lee and reminisce about old times.

Yes i have a reynolds painting of a two boats. And a small house behind it by the Sea Cant find anything on it. On the back only a few markings saying style A 024 Made in Mexico. thank you for your Help.