“Dark Landscapes for a White House,” Deborah Oropallo’s solo exhibition at Catharine Clark, presents a moody, dysfunctional picture of contemporary society in nine large-scale works in photomontage, pigment print, and paint on paper, complemented by a quartet of single-channel digital videos. The darkness takes two forms, natural disaster—fire, flood and famine—and unnatural disaster: the incomprehensible train-wreck of the 45th presidency.

Meltdown (all works 2018) juxtaposes chunks of white—suggesting icebergs or glaciers—gray scummy surf, and shiny red tubes like oozing lava. Oropallo, in a concise way, conflates ecological disasters of global warming and oil spills; the viewer’s awareness of how both kinds of disasters are denied or dismissed by the current administration provides a sobering undercurrent to the image. Here, as is consistent throughout the work, it is impossible to completely distinguish what is digitally-manipulated photo from what is painted. This elusiveness of the ability to attribute gesture has become a signature aspect of Oropallo’s style.

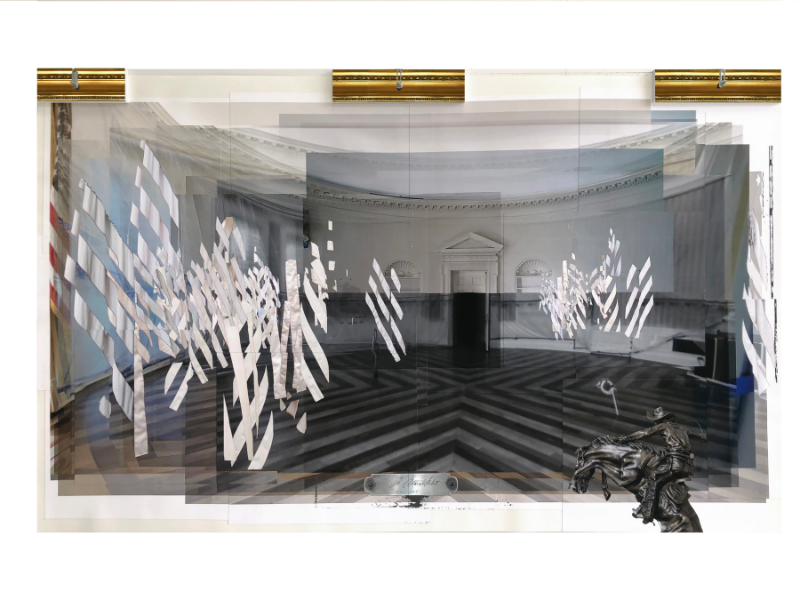

The Bronco Buster (1895) by Frederic Remington, an iconic Western sculpture displayed in the White House since the Nixon administration, storms the picture plane, adjacent to a faux-embossed signature “D. Oropallo 1861-1865.” These two pictorial elements anchor nearly all the works, the dates alluding to the term in office held by President Abraham Lincoln, who attempted to steer a moral course for the country during the divisive Civil War.

In the media room, the digital video Oval O, accompanied by the plaintive funk soundtrack of Marvin Gaye’s Inner City Blues (1971), displays flashing shots of the oval office. Ghostly images of past presidents flicker through. Deconstructed images of the American flag, mostly its stripes, shifted to a frightening black and white icon, blot out increasing sections of the scene. Nostalgic images of Barrack Obama are particularly poignant, recalling the former dignity of the presidency. As Obama disappears, to be replaced by Trump, along with Kellyanne Conway and Steve Bannon, Gaye intones: “Make me want to run and throw up both my hands… This ain’t livin’.” Oropallo’s collaborator on the audio component for the videos is sound designer and composer Andy Rappaport.

Blazes, the largest pigment print, presents what looks like a tract of homes with white clapboard siding; one building is charred black. Others crumble and fall apart as though whipped by a tornado. The demolition of a white house is clearly a visual pun, a reference to the moral and philosophical destruction being wrought in Washington; simultaneously, it evokes the chilling aftermath of actual physical disaster. Oropallo herself lives not too far from the path of the recent devastating Santa Rosa fires.

Oropallo clearly responds to the mind-numbing effect caused by oversaturation of images in our daily lives. Mining popular culture—here, the internet—for content, has strong antecedents in the works of Warhol, Rauschenberg and Richter, among others, although she has her own unique slant on appropriation. Her skillful manipulation of images and sounds, of scale and focus, confronts the viewer with a carefully crafted experience, one designed to elicit a powerful and visceral reaction.