Can art hurt people?

In mid-February, I sat in Boyle Heights’ El Tepeyac café across from a revolutionary named A. and probed him with questions in order to find out. A., a slim Latinx man wearing Elvis Costello glasses, belongs to the anti-gentrification group Defend Boyle Heights. DBH is a nationally recognized rebellion against the encroachment of art galleries into communities of color, and also forms the subject of an LAPD hate crime investigation.

“This is our neighborhood, we were raised here,” A. told me, staring down at the uneaten burrito he’d ordered. “We have a stake in it, and we tell them—you are not going to build this art gallery here. Get the fuck out! Private property be damned!”

I first contacted A. through Defend Boyle Heights’ website after reading about DBH’s riotous July, 2016 interruption of a coordinated dialogue about art and gentrification staged by Self Help Graphics and Art, the revered neighborhood gallery devoted to showing Latino and Chicano work. DBH’s fame had enlarged considerably since then, particularly after protesters laid siege to the Venus and Nicodim art galleries on Anderson Street. That September, DBH-ers, some wearing bandanas over their faces, massed on Anderson, yelling Fuera Fuera Fuera! while Venus and Nicodim patrons peered at them skittishly through the plate glass. Some demonstrators (possibly unaffiliated) also shot potato guns at the windows. And one dissident, whom A. insists did not belong to DBH, sprayed Fuck White Art on Nicodim’s door, spurring the LAPD to open a hate crime file.

“How do art galleries hurt you?” I asked, sipping my cooling decaf.

“[DBH] got started in November of 2015.” A. stared at me with huge, earnest eyes from behind his lenses. “There was an action against Hopscotch. It’s an [majority Anglo] opera or theater troupe. They showed up in Hollenbeck Park. An organization called Serve the People of L.A., which does food distribution, sets up at the park every Sunday [the Hopscotch cast showed up there to rehearse a show]. Serve the People saw them and thought: ‘This is an obvious project for gentrification. You’re a bunch of fucking gentrifiers, and we want you to leave.’ That’s when we realized that we needed to move against arts organizations, the galleries.” According to Serve the People’s own website, its members had a “confrontation” with the company’s rehearsing players at Hollenbeck, and warned them that “their very well-being [was] at risk.”

DBH grew out of that action: It acts as a coalition with Serve the People, Union de Vecinos, Ovarian Psycos, the Brown Berets and Backyard Brigade. Together, these networks also form the Boyle Heights Alliance Against Artwashing and Displacement (BHAAAD), which targets art galleries’ “artwashing” of gentrification.

In resisting galleries, Defend Boyle Heights responds to a received wisdom that arts institutions attract wealthy people to “undiscovered” neighborhoods that swiftly see rent rises. Poor communities have worried about arriviste galleries since at least the 1970s, when Paula Cooper moved her renowned white box into SoHo’s “Hell’s Hundred Acres”—though the connection between art and poverty arguably ranges back to Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s mid-19th-century Paris renovation, which simultaneously saw the exile of indigents from their habitat and the appearance of privately owned salons around the Tuileries.

Some economists reject the connection between art galleries and prohibitive land values: In 2013, USC’s Jenny Schultz published a study concluding that art gallerists were “unlikely” to cause gentrification, and could only be faulted for spying up-and-coming neighborhoods before prices blow up. A more trenchant appraisal of DBH’s agenda observes that a violent fight against gentrification wastes political bullets, most of which will probably ricochet. As sociologists at the University of Toronto and Stanford argued in a recent paper about “extreme” political protest, tactics that involve threats “typically reduce popular public support for the movement by eroding bystanders’ identification with the movement.” A far more viable neighborhood preservation model will be found in Houston’s largely African-American Third Ward, which has resisted gentrification under the careful land-banking efforts of Texas State Representative Garnet Coleman. Coleman protected the Third Ward through negotiation and sober economic planning with community members and arts organizations—not by scaring people.

Nevertheless, with Boyle Heights’ property values spiking 9.3% in 2016, it is gentrifying, and A. emphasized that DBH and BHAAAD’s activism against art galleries springs from locals’ sensation of getting pushed out: “On a Friday or Saturday night, in the arts district, we are surrounded. And we can’t afford [what’s coming]. I used to live in this apartment paying $600 a month, and a family of six lived there, too. Now, it’s $1,900 a month for a two-bedroom loft. I mean, it’s frightening.”

Boyle Heights gallerists don’t express much sympathy. A week after I met with A., Nicodim Gallery’s elegant, white-haired owner Mihai Nicodim swept his hand in the air when asked about the September protest. “I am from Romania, so it’s nothing. But, no, you cannot tell me to leave. It is very dangerous, they had potato guns. They didn’t like white people here. What is the difference between [what DBH says] and Trump?” Nicodim started laughing. “I have an opening tonight, and you know what I did? I sent them an invitation. They didn’t like that. I put it on their website. They just take it off.”

Other Boyle Heights residents, such as housing advocate Margarita Amador, echo Nicodim’s frustration with DBH: “They’re like gang members. They’re anti-change. I don’t agree that the battle is white people, [race] is irrelevant. And we need tax revenue.” But Amador also recognizes the damage that gentrification can do to poorer, elderly people, particularly those thrust out of their homes in the cash-for-keys scams that often accompany escalating property values: “We can’t afford to move any more of our senior residents.” She’s already seen the grim effects of dislocation in Pico/Aliso, she says. “At least five residents passed away when we relocated them. They get sad. They get lonely. They were missing the community, and here, you know people by name.”

: : :

It seems that everywhere you look in Boyle Heights, someone is suffering as a result of gentrification and its blowback. On February 22, the administrators of PSSST gallery, a prominent target of DBH protest, announced their closure on their website. “Our staff and artists were routinely trolled online and harassed in-person,” the gallerists said in a statement. “This persistent targeting, which was often highly personal in nature, was made all the more intolerable because the artists we engaged are queer, women and/or people of color.”

At the time of my interview with A., DBH still worked to dislodge PSSST from its East 3rd Street location. “Don’t you feel bad about making people who work at that art gallery feel terrible, and maybe even frightened?” I asked.

A. shook his head: “I’m not actively wishing suffering upon them, and we always have to reiterate we don’t hate art. We hate the economic process, what’s happening to the working-class residents. But if that’s what it takes for them to understand that gentrification is a terrible process and displacement is a terrible thing to go through, then yeah, feel how painful this is to see your community get swallowed up by an economic train that’s trying to run you over.”

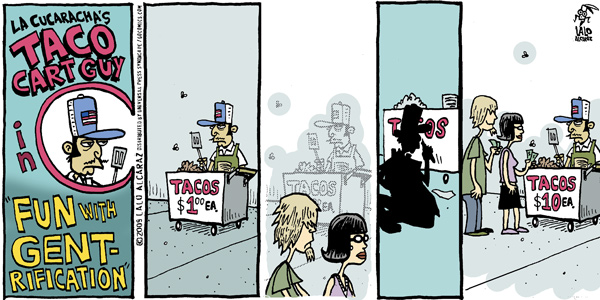

In Boyle Heights, art isn’t the force hurting residents—hell, as usual, is other people. Who is at fault? Lalo Alcaraz, the artist and Self Help Graphics affiliate, posted on Facebook last July: “I’m all against gentrification… [but DBH’s] attacking Self Help Graphics… is just plain WRONG.” In a recent phone interview, Alcaraz explained that he himself has experienced threats: “[So,] I stand by what I said. I just don’t agree with violence or intimidation… It’s not the way to do things.” To this critique, we might also add that it’s imperative to reject persecution of queers, racial minorities, and women, as well as the noxious use of racist rhetoric.

If we look to the state to help break this feedback loop of homelessness and harm, it would only offer the bitter exigencies of the criminal justice system to enforce anti-discrimination laws. Those of us who remain wary of criminal justice’s brutal power balk at the idea of a social justice effort that would meet with yet another police sweep of Latinos. The fight over art galleries in Boyle Heights is a story of overlapping structural racism, classism and homophobia, and the real trouble here comes from the fact that, in Amador’s words, the players don’t “know people by name.”

The July 2016 dialogue hosted by Self Help Graphics devolved into a hostile carnival. But mutual recognition and dialogue could have formed the heart of so many imaginative responses to the change of Boyle Heights’s fortunes. Anything from the traditional—such as community benefits agreements—to the radical (e.g., talking circles) might have repaired the rift that threatens to install hate alongside the neighborhood’s freshly painted galleries and clothing shops.

“People are being evicted, and it’s a loss of home, a loss of culture,” A. explained that day at El Tepeyac.

Maybe there’s still time to address inequality in the neighborhood with some fresh thinking. Along with Houston’s Third Ward, Chicago is a leader here: the artist Theaster Gates opened the Dorchester Art + Housing Collaborative in 2009, and art galleries like Weinberg/Newton have housed homeless people. Such innovations could help defuse the distrust that leads to potato guns, slurs, and possibly worse. And so far, nothing seems irreversible.

In my conversation with A., he proved a sensitive militant who listened to other opinions when approached with respect. Couldn’t that be a starting place for change? Nemeses have put aside their aggressions before, and in far worse worlds: In 1947, Mohandas Gandhi lived under the same Calcutta roof as his supposed ethnic enemy, Bengal’s Muslim League Chief Minister Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy. Maybe there will never be another Gandhi, but his legacy is at least as compelling as the implications of internecine war and race and class cleansing that vibrate in some DBH-affiliated propaganda. Peace remains possible: It’s not too late to voice the pain of dislocation while working to create community and cooperation in Boyle Heights.

0 Comments