On a clear sunny day there’s a press preview for the ambitious “@Large: Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz” exhibition. Famous for its former use as a prison, with notorious inhabitants such as Al Capone, George “Machine Gun” Kelly and Robert “The Bird Man” Stroud, its layered history also includes dramatic political protests of 1969–71 when the island was occupied by Native Americans. Currently, the island is also a protected bird habitat, as well as one of the most popular national park.

Gallerist and founder of the FOR-SITE foundation Cheryl Haines invited Ai to bring his artwork to Alcatraz back in 2011 when visiting his studio in Beijing. FOR-SITE foundation enables artists to create site-specific works to engender dialogue about cultural and environmental issues.

Conceptual artist Ai Weiwei’s engagement with political activism has lengthy roots; his father, Ai Qing, an accomplished poet who fell into disfavor during the Cultural Revolution, was humiliated and sent for “re-education” through manual labor in the remote countryside. Ai Weiwei grew up emotionally removed from the China which had treated his family so poorly, and as a young adult left to pursue the life of an artist in Paris and New York, returning to China in 1993.

Called by some “the world’s most powerful artist,” Ai achieved global notoriety for his collaboration with Heurzon & de Meuron on the “Bird’s Nest” stadium for the 2008 Beijing Olympics, and his subsequent protest of the event. He began a passionate quest for disclosure of facts around the tragic death of schoolchildren in the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake.

Detained and beaten by the police—badly enough to require surgery for a cerebral hemorrhage—Ai was later incarcerated for 81 days; his passport was also confiscated. Ai Weiwei’s experience of prison from behind the bars, as well as his engagement with political action, have uniquely prepared him for the task of responding to the complex history of imprisonment and protest on Alcatraz Island.

“@Large” has seven complex site-specific installations in three separate locations on the island. Teams of volunteers and assistants assembled and installed the component pieces for each work, some of which had been constructed in China before being sent to Alcatraz. Upon entering the New Industries Building, one is immediately met by With Wind, specifically by the head of an immense—and confined—dragon kite. Joyful colors and patterns offer a stark contrast to the bare concrete structure of the building: a backdrop of dusty sinks, electrical conduits and disused junction boxes. Approaching the rear of the building, look down; the floor-mounted Trace uses 1.6 million vibrant LEGO blocks to create high-contrast portraits of 176 prisoners of conscience from around the world. Some are iconic civil rights activists, such as Martin Luther King, Jr. and Nelson Mandela, most are lesser known. With its sobering content, the work is masked in colorful hues, sugar-coating a bitter pill.

I ask Haines about obstacles they had to overcome working on the project…which was the worst? “Lack of time,” she replies, “this was an extraordinarily fast-paced project.” With Ai presently under house arrest in China, she adds, “Ai Weiwei has had many international exhibitions where he hasn’t been present. Granted this is seven new works, site-specifically commissioned, that adds a little bit of complexity to the conversation. But because of his innate ability to understand the built environment and to interpret plans and architectural models, what you see as the end result is pretty close to what we envisioned.”

Refraction, the most challenging piece, is a massive sculpture inspired by a bird’s wing. Installed on the first floor of the New Industries Building, its “feathers” consist of reflective panels from Tibetan solar cookers. Our interest in the physical object itself, in getting a better look at it, is thwarted by the manner in which Ai has chosen to display it—one may only view the work through small cracked windows in a long hall, “gun gallery,” overlooking the room, which enabled armed guards to monitor the activities of prisoners working in the hall beneath. This theme of surveillance, along with the bird’s-eye view of the piece, echo Ai’s earlier dioramas of his own period of incarceration. Our frustration with seeing, but being unable to approach, is central to the work.

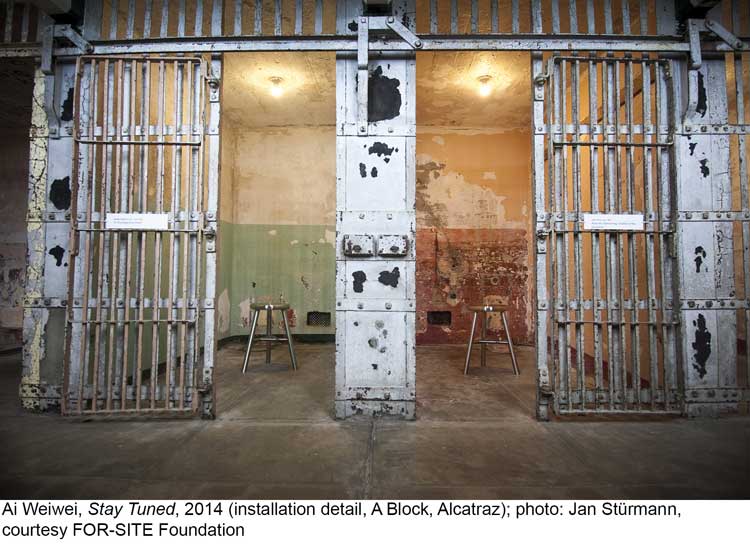

Entering A Block, Stay Tuned offers entry to each of 12 cells filled with individual soundtracks of singing, chanting, speech or music, including that of Russian activist punk band, Pussy Riot. From 1934 through 1937, silence was imposed in Alcatraz—no talking among the prisoners was allowed, and the importance of communication to a free society underscores “@ Large.” Intriguing conceptually, it’s a bit hard to engage with the content of the work amid other journalists jockeying for promising angles.

Up the stairs, in the rather eerie hospital wing, there are two more works. Another sound installation, Illumination, fills two tiled rooms that were used as psychiatric observation quarters with chanting—by Tibetan monks in one, in the other, Hopi Indians. With a sterile, clinical feel, this gives me the chills. Ai here links the human rights violations perpetrated by China in Tibet with abuses the United States inflicted on its Native American population, including the incarceration of Hopi Indian tribe members here in the late 19th century.

Poignant and poetic, Blossom fills sinks, toilets and bathtubs with encrustations of white porcelain flowers. The title of the piece alludes to the brief period in 1956 when the People’s Republic of China advocated freedom of expression, with the slogan “let 100 flowers bloom.” A final interactive installation in the prison dining hall, Yours Truly, enables visitors to act, offering pre-addressed postcards to be sent to support prisoners of conscience around the world.

One may clearly draw positive conclusions about the state of freedom of expression in the United States, or at least in the San Francisco Bay Area, by the fact that the FOR-SITE foundation found in the National Park Service and the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy such willing partners to disseminate what might be considered as potentially subversive content. Haines’ advice for promoting Ai’s cause? She advises, hoping to create a dialogue, “Share the concepts of the exhibition. Tweet, Instagram, email…talk about the major issues brought forth in this project.”

As virtual reality increasingly usurps our experience of direct sensation, the question of whether one can truly create a “site-specific” installation from afar is problematic. Bold, direct, aesthetically sound and conceptually transparent, “@Large” challenges visitors to take responsibility for their actions—or lack thereof—addressing the issue of human rights abuse around the world; regardless of its level of specificity, the artist may well consider it to be his masterpiece.

@Large: Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz

Through April 26, 2015 at Alcatraz Island

for-site.org/project/ai-weiwei-alcatraz/