How apt that the new Cheech Marin Museum for Chicano Art and Culture in Riverside, California should open in a repurposed public library. Libraries are historically accessible spaces for learning and intellectual research. Museums, on the other hand, still struggle to make themselves approachable—not to mention equitable. Not so with The Cheech, as it’s affectionately known.

“I first learned about art in a public library,” says the namesake collector Marin over a Zoom call: “It was part of a family assignment.” This new visual “library” resonates with a vibrant urgency unlike any other museum in Southern California. The Cheech—an adjunct of the Riverside Art Museum and housed in an understated mid-century building—outwardly belies the permanent collection and rotating exhibitions that it now houses. Since its opening it has been hosting 2,000 visitors a day, virtually at capacity

Marin, the actor and comedian known for his marijuana pranks in the infamous Cheech & Chong films with former partner Tommy Chong, is animated and enthusiastic during our Zoom call. By the mid-’80s, he tells me, “I was beginning to make money.” The first works he collected were three small paintings by Frank Romero, Carlos Almaraz and George Yepes—and the buying continued with a vengeance. Figuration is a hallmark of the collection; he collected what he liked—not as an academic exercise, but rather as an attempt to raise awareness of the Chicano art narrative. Over time his trained eye acquired some masterful works, and the collection now reads like an essential who’s who of Chicano artists—admittedly with some gaps. But this doesn’t pretend to be a historical narrative, or an all-encompassing survey of Chicano art. Marin is considered the foremost collector of the genre. He has amassed over 700 works and continues to acquire more.

Ever malleable, the definition of Chicano is born out of the activist period of the 1960s. Not confined to California, the movement and concomitant art was also notably manifested in Texas and New Mexico, as well as other states. Scholar and artist Dr. Amalia Mesa-Bains observed: “The DNA of the Chicano term—social justice—is still embedded in its meaning and, while there is no conclusive definition, it remains more relevant and expansive than ever. The museum has propelled ‘Chicano’ back into the forefront—ultimately, it’s American art. I think he [Marin] assembled preeminent representations of the genre.” Cheech amplified this vision, concurring, “Each generation builds on the original intent: Latino, Latinx, Chicanx and others.”

Cheech Marin. Image courtesy of the Riverside Art Museum.

The existing Riverside Art Museum had previously mounted an exhibition of Cheech’s collection with a record-breaking public response—something the city and museum leaders, headed by Executive Director Drew Oberjuerge, wisely took note of. They just happened to have an empty library that needed a new purpose. After some negotiations and an offer to house Cheech’s collection—an offer he couldn’t refuse—a public/private partnership emerged. With considerable heavy lifting and fundraising, the renovated library was transformed and completed in a record five years; Marin gifting 500 objects from his collection to the center. The city will assist the museum with ongoing operating funds—the kind of stability that is crucial to a budding institution and support that bodes well for its future.

What’s clear as you walk into the museum is its commitment to the Inland Empire’s (as Riverside County and its surroundings are known) local community artists, who are featured in a rotating display in the breezy ground-floor atrium. During my visit, multi-generational families crowded around the exhibit and lingered while discussing the works with respect and admiration. I can’t think of another museum that’s made its commitment so conspicuous and permanent. The museum’s footprint includes rotating galleries dedicated to 95 works from Cheech’s 500-plus gifted collection. Included are well-known artists Vincent Valdez, Carlos Almaraz and Margaret Garcia—and there are many revelations, such as standouts Jeannette Herrera and Joe Peña of Texas and Carlos Puma of Riverside.

Herrera’s work This is the End (2013) is, as she comments, “somewhat older, but significant; it was done at a difficult time in my life.” The picture portrays the artist’s imminent marital breakup. Preoccupied and unsettled, it is a tableau of an uncertain future. Peña spent time in New York working in galleries and was influenced by Modernist inclinations. His work 1:15am, Final Stop (2016) is an atmospheric painting that has a less dramatic backstory than one might assume. “My wife was pregnant, it was late, and she suddenly sent me out for tacos to the local truck. When I arrived, it was shrouded in darkness—as if hovering in space” says Pena. “It’s important to me to capture these moments of local culture.” The picture is a masterful vignette of mood and light—a kindred spirit of Edward Hopper.

Jeannette Herrera, This is the End, 2013. Image courtesy of the Cheech Marin Collection and Riverside Art Museum.

Vincent Valdez’ Great Grandfather (1999) is a self-portrait of pensive memories painted in an emerging classical style—using house paint. The artist is foregrounded with the image of his great grandfather in the background surrounded by cultural icons. “My great-grandfather was an artist and an inspiration. I painted this in my junior year at the Rhode Island School of Design. I was the only Chicano there and this helped me adjust,” says Valdez. These works share moments of human sentience—love, loss, pain, remembrance—the universality of the mortal condition.

A separate installation of Einar and Jamex De La Torre’s retrospective, guest-curated by the Getty Museum’s Selene Preciado, is a sensational visual spectacle that occupies the second floor, a designated display gallery that will rotate Latino/Chicano artists with the next exhibition by Judithe Hernández.

The inaugural opening has already had an impact on National and International art circles. “The response has been immediate and global,” says Marin. As for his continuing collecting aspirations, “There are gaps and I want to fix that.”

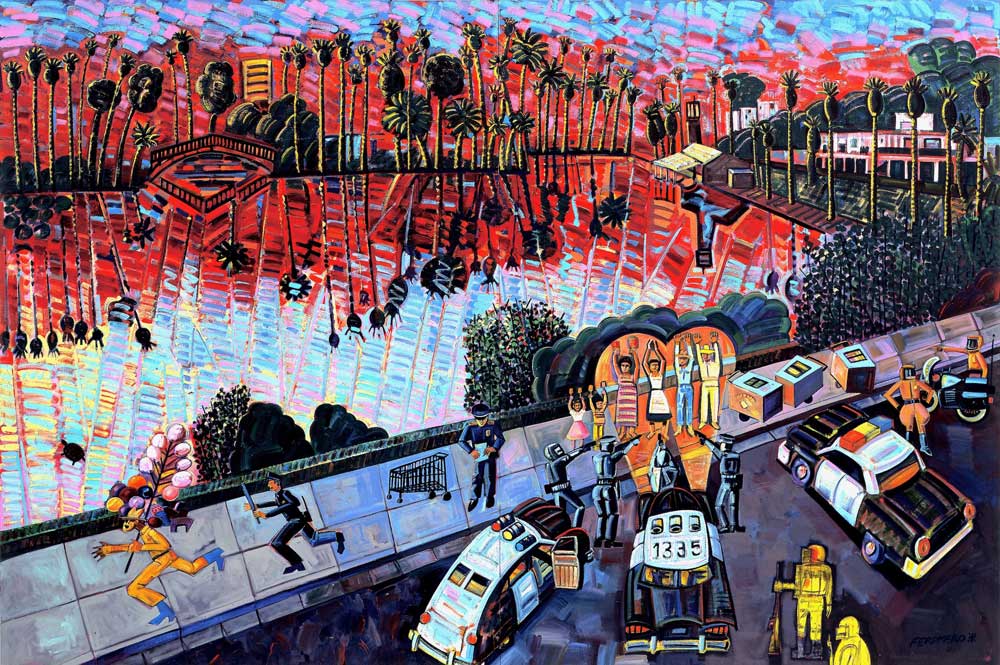

Frank Romero, The Arrest of the Paleteros, 1985. Image courtesy of the Cheech Marin Collection and Riverside Art Museum.

Artistic Director Maria Esther Fernandez was hired from Northern California’s Triton Museum to head The Cheech’s curatorial program. Her plan includes ratcheting up research scholarship, in-depth presentations of solo artists, and establishing an advisory committee to help craft an art-acquisition strategy. In a recent post-opening walk-through, I asked Fernandez what the key objectives were for this new museum: “Our hope is the center will reflect the complexity and richness of the community which has been historically underrepresented in mainstream cultural institutions.”

She has her work cut out for her: raising awareness at a national and international level, bringing recognition to work that has so often been ignored. Long overlooked by the traditional academic canon and art gallery consiglieri as “folk or marginal art,” Chicano artists’ profiles and viability will be greatly enhanced by the existence of The Cheech.

It’s hard to imagine a more rousing and auspicious museum debut.