One artist who is returning to his roots after spending the last several years working on massive projects is sculptor Charles Long. For his next major exhibition “Up Land,” at his gallery Tanya Bonakdar in Chelsea, Long is embracing his personal style of hands-on production, which made him popular years before any of HIS major projects.

Working as Long’s studio manager through many of those large projects, I have been privy to an insider’s point of view to his process and style of making art on a grand scale. I was invited to his studio at the base of Mt. Baldy (an hour’s drive east of downtown Los Angeles), not to reminisce about old wars fought and won together, but rather to talk about his current body of work (sans assistants), the art market, his life and what is on the horizon.

Unassisted

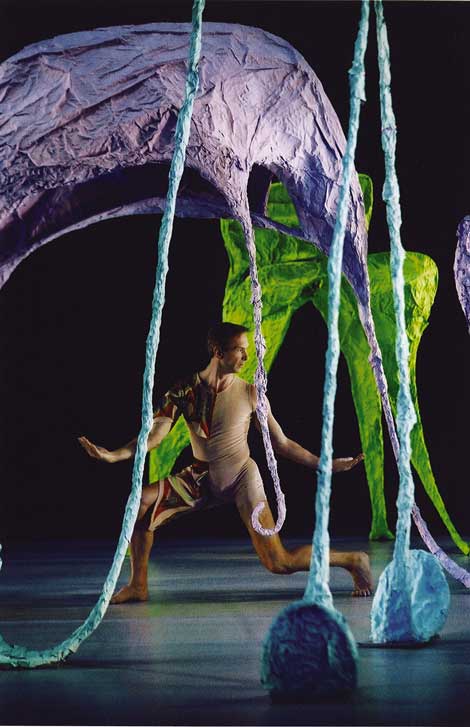

Immediately upon entering his studio, I see what Long lovingly refers to as his “sculpture graveyard.” There are tall shelves of his personally archived works, representing moments of creation for Long over the past three decades. Atop one of these shelves, I spot a neon green sculpture wrapped in plastic, titled Fancy (1989)—which Long created as the first piece in a series of works in the late ’80s and early ’90s. This sculpture provided inspiration for a stage set that he created for Merce Cunningham. Decades later, Long notes that Fancy, as it was stored upside down on that high shelf for safekeeping was the impetus for new work. In many cases, what is important to us in life and art does not change over time, only the perspective with which we see it.

My first realization about Long’s sculptures for the “Up Land” exhibition is that they are strikingly different from previous works—not necessarily aesthetically, but rather in their nontangential use of materials. The sculptures are heavily process-laden, created initially from wax to facilitate their eventual transformation into bronze. It is a method of sculpting bred out of the necessities of the traditional foundry process, while embracing what is uniquely special about archaic lost-wax casting. Long explains the new direction: “I am not working in bronze in the way that bronze has become popular again; strangely I think that has a lot more to do with money. For me, it has to do with making something that connects to things that have been made for thousands and thousands of years, and working in the most direct way possible.”

With a decision to predetermine a singular material, Long has allowed his focus to be solely on other aspects of the work, like concept and form. “In the past I really thought it was so important for the materiality and the process to be a part of creating the meaning, as well as the shapes and the references creating the meaning. I am done with that.”

Charles Long, “Memory Print Boutique” (detail), 2014, in collaboration with Eluvium, Brady Foster, Seth Hawkins, Emery Martin, Michael Mascha, Carrie Paterson, Karen Reitzel and Solid Concepts. Installation view, “Catalin,” The Contemporary Austin– Jones Center, Austin. Courtesy the artists and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery. Photo by Ben Aqua.

Hearing him say this, I can hardly believe my ears. The last major project I oversaw for Long was his hefty museum exhibition in Texas, “CATALIN,” which opened earlier this year at the Contemporary Austin. The exhibition took its name from a beautiful yet highly toxic resin which was used heavily in the production of household goods from the ’30s to the ’50s—thus setting the conceptual stage with dark eco-decadent undertones.

Nearly overtaking every room of every floor of the museum, “CATALIN” even spilled out onto the exterior by using the rear projection video screen on the building façade. The artworks in the exhibition were made with hundreds of materials—all styles of visual, sculptural, auditory and scent-based creation were implemented in the process. This task necessitated a small army of talented collaborators (many of whom were successful artists in their own right) and fabricators to accomplish the final aesthetics; eventually we even teamed up with the SXSW music festival and the exhibition became a venue for several performances.

When speaking about materiality, Long states: “I think I really kicked its ass in the Austin project by using the water from the fastest melting glaciers to make perfume, spandex made from recycled bottles to make giant sculptures, huge architectural reliefs made from mushrooms.” Long expresses that while “CATALIN” was his ultimate project in using process and materials to create meaning, “Up Land” also does so, but in a more subtle way.

Charles Long, AC/AC and the Climate Controllers (detail), 2014. Mixed media. Dimensions variable. Installation view, CATALIN, The Contemporary Austin – Jones Center, Austin. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery. Photograph by Brian Fitzsimmons.

In reference to the works in this upcoming exhibition, Long puts it simply and lays his cards on the table. “I can’t make sculptures that somehow blow you away in the way that these ideas have blown me away. I am actually just going for the basic thing—I feel humble—and would rather do this than overreach and promise you more than is in the object.”

The mention of the current all-too-over-promised art object gives me a segue to chat about the blue-chip art market. We speak about commerce and bureaucracy crushing the artistic vision, worldwide galleries, globalization, art fairs and the unrelenting pressure these issues can put on the artist. How could the vision not be sacrificed? How could the art not eventually become diluted? Long replies, “Mine would be severely sacrificed. I have discovered that my art is really about not knowing what it is I am doing. That is why every show looks different; I am always going back to square one.”

This body of work echoes some deep theories that have been explored in Long’s previous sculptures, specifically Gottfried Leibniz’s philosophy of “monadology.” (Leibniz, a German mathematician and philosopher is controversially credited as the co-creator of Calculus. His theory of monadology is—in greatly simplified terms—an inspired thinker’s summation of the world, matter, mathematics and theology, monastically centering around a simple substance, a monad.)

Long comments that his “misinterpretations” of Leibniz’s philosophies while sitting with a sketchbook and a glass of wine helped to shape his new work. Fragments of these sculptures open up in a much more representational way. Long tells me, “I am not surprised by this turn. I have tried so hard to deal with the human subject without ever representing it. For all these years, I have never had the figure in my work, and I have always known that at some point we were just going to get drunk and go to bed together. It will be me alone in the studio and I will just be sculpting the full figure. The return of the repressed!”

Long has obviously not reached this figurative extreme for “Up Land,” but he does conjure up a nice visual. When referring to the figure as it relates in context to the current body of work, Long is speaking of the small elements that he refers to as the “monads,” one of which will rest atop each of a multitude of curving bronze rods rising from amorphously sculpted sections. Each of these bronze sections are perched precariously on a deconstructed geometric base. Upon inspection, these monad sections do have the familiar stylized feel of a long-buried but recently excavated talisman or other piece of ancient ephemera. They are both abstracted, but have a human quality.

While his new sculptures possess contemporary aesthetics, the initial inspiration came to him from days spent exploring ancient relics in the back rooms of the Metropolitan Museum of Art with his son, Gene.

In the Company of Others

Speaking with Long about studio assistants, his creative process and his own experiences, he recounts his formidable years before turning 30, while working for the acclaimed artist Terry Winters. He jokes that his primary role was not actually assisting with the making of the paintings, but rather other studio duties. “One of the things Terry utilized me for quite a bit was curating his music. He would send me out for something at the hardware store, and would say ‘go over to Other Music, get whatever you think we need.’ I enjoyed that a lot.”

In that environment—if personalities don’t gel—it can be disastrous. Long laughs while recalling a similar situation where he just knew it wouldn’t work out with a former assistant. “He didn’t know who Ziggy Stardust was—we just had to part ways. For me the assistant is a really important part of the mood of the project; whatever the project is, you want to have the right vibe.”

It is not a far stretch to equate a traditional artist/assistant role to a marriage of sorts; there are few people with whom you truly want to spend the majority of your hours with each day, but when you find the right match it will stand the test of time. As someone often does when thinking back to the good old days, Long chuckles (almost to himself) as he reflects back to his early times at Terry Winters’ studio. “I couldn’t believe how young I felt in proximity to him. I felt honored to be part of what he was doing. It was a very classic mentor situation, and I just saw him a week ago. As we have gotten older, we have only become closer.”

Talking more about his time with Winters and about his upcoming “Up Land” exhibition, Long recalls the great mood in the studio while he and Terry were preparing for one of Winters’ exhibitions in 1989, one of the last as artist and assistant. “That period of his work is really influencing what I am doing right in this very show. As assisting goes, that was a fantastic thing. I mean it is still here in this studio, that time that I spent with him.”

As the conversation turns away from his personal days as an assistant and more toward a broad commentary on artists’ assistants, he smiles charismatically. “I think there is a sweet spot where it is a really good place to be an artist’s assistant; it is the one where you are working for an artist who doesn’t really need you to make the art.”

This seems like an ideal situation: the brilliant artist solely creating masterpieces in the studio while the assistants deal with the menial tasks that simply need to get done—yet how does this fit into the current rubric of a worldwide art market?

As I press him yet again about the level of production coming out of some artist’s studios and our present-day view of art-making, the smile returns to Long’s face. “We live in a period more like the Baroque—where Paul Rubens probably never got near his paintings. We live in a time when you can assist and the artist never touches the art; you can be completely involved but are you really involved in what the art is about? Is the art about anything? Is Paul Rubens’ art really about anything other than big chunky thighs?”

Charles Long, “Pet Sounds” (detail), 2012. Installation view, The Contemporary Austin. Courtesy the artist, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, and Madison Square Park Conservancy. Photo by Ben Aqua.

PUBLIC DISPLAY

During my tenure working with Long, there was never a moment’s break. As I bring up these times, he pauses for a moment; I can only imagine that he is mentally scrolling through the thousands of emails and on-site visits behind making those projects happen. He finally answers that artists should be ambitious and take on massive projects—saying that some works are as simple as, “the more you put on, the better.” While sometimes this may be the case, Long looks at his public practice in a much different way. “The pieces that I like to make, when you get into the big scale, it is really like trying to steer a giant ship. You might avert the iceberg but are you going to truly hit your target?”

Long recently has been making interactive art using new technologies—and there are definitely a lot of icebergs to negotiate. Pondering and reflecting back on his recent publicly collaborative works such as “Pet Sounds” (2012) and Fountainhead (2013), Long states, “When I had to think about making a piece that was going to be in the center of Manhattan, outdoors all summer, it wasn’t okay for me to just do my signature thing. I didn’t want to do that. It is almost like I am having a different conversation. It is like making love to somebody and thinking about somebody else. Which is fine, except that it is the public that is thinking about somebody else. And maybe I had given them reason to.”

Charles Long, Pet Sounds (detail), 2012. Powder coated aluminum, fiberglass, and electronic components. Dimensions variable. Installation view, The Contemporary Austin – Laguna Gloria, Austin. Courtesy the artist, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, and Madison Square Park Conservancy. Photograph by Brian Fitzsimmons.

My personal experience with “Pet Sounds” has shown that the public is thinking about absolutely no one else. It is as simple as stopping for five minutes and watching the people interact with the artworks; the smiles provide all the evidence needed. Old and young alike light up when the sculptures buzz, purr and vibrate as each different “zone” on the brightly colored blobs are activated through “petting” the objects. This is not consumerist art solely reserved for the fiscally elite, but rather something uniquely accessible by the general populous. A more accurate interpretation may be that while the general public is viewing a different static piece of plop-public art, they are actually thinking about “Pet Sounds.”

At times, the stress and compromise inherent to those big projects cause an artist to lose sight of the societal importance of the objects they are creating. These works give the public a reprieve from the daily norm. The magic the object instills into the world transcends its physicality. It is easy for an artist to sit back in the studio and live within their comfort zone. As a society we should applaud those who truly step out, avoid the icebergs and add something memorable to this world.

For an artist whose career has taken many turns over the years—one who admittedly reinvents himself every exhibition—the future may never be known. Again, it seems Charles Long works best that way. Reflecting on the time spent with Long as his studio manager, and even more now during our conversation, I think he sums it up nicely in his own words: “I love Nietzsche’s idea that you live like you are writing a myth— that has always made sense to me.”

See Charles Long: “Up Land,” Sept. 11–Oct. 18, 2014, at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, 521 West 21st Street, New York, NY; tanyabonakdargallery.com