Your cart is currently empty!

Category: *SEPT-OCT 2022

-

The Armory Show

It’s Armory Week here in New York and the city is back in full force. With four major fairs–The Armory Show, Independent’s new 20th Century edition, SPRING/BREAK and Art on Paper–and countless exhibitions, events, pop ups and public programs, there is no shortage of art to see. As the anchor of the week, The Armory Show presents one of the best opportunities to see new and coveted artists from the biggest names in modern and contemporary art.

Returning to the sprawling Javits Center, The Armory Show opened to the public today and runs through Sunday. While fairs can tend to mirror exactly what’s on view at the galleries just a few blocks away, this year’s Armory is a refreshing and welcome opportunity to view artists and exhibitors from outside of New York. Featuring over 240 booths and a selection of public works installed off-site at the US Open tennis tournament, the fair is as vast as ever.

Voloshyn Gallery’s Booth at The Armory 2022. Image by Annabel Keenan. A standout booth is Kyiv’s Voloshyn Gallery, which brought new works by Lesia Khomenko and Nikita Kadan that explore the current and historic role of war in Ukraine. Khomenko’s figural paintings were made after the war with Russia began in February. Unable to share photos to protect the safety of soldiers, those taking refuge outside of Ukraine often rely on the media’s blurred and pixilated images to visualize their loved ones still fighting at home. Depicting partly obscured soldiers, Khomenko highlights several of the concerns facing Ukrainians today, including how friends and family fighting in the war are stripped of their identities and reduced to numbers and figures.

Mazzoleni’s booth featuring Rebecca Moccia at The Armory 2022. Image by Annabel Keenan. Also making the trip from abroad is Mazzoleni, a Torino and London-based gallery specializing in Italian art. Included in their presentation are new works by Rebecca Moccia that are part of the artist’s ongoing “Ministry of Loneliness” artistic and research-based project. Moccia explores emotional states, in particular our relationship with pain and loneliness. In one work displayed across an entire booth wall, she shared results from a survey in which she questions the role of the Ministry of Loneliness, an actual ministry in several countries including Japan and the UK. Survey participants came from all over the world, pointing to the collective nature of loneliness, amplified by the pandemic.

OSL Contemporary’s booth featuring Ane Graff at The Armory 2022. Image by Annabel Keenan. Oslo-based OSL Contemporary put together an elegant, visually stunning presentation of silk paintings and resin sculptures resembling goblets by Ane Graff. Despite their beauty, the works are based on the artist’s research into how environmental risk factors impact mental states. Softly blowing as visitors walk by, Graff’s abstract silk paintings with rich red, pink, and brown hues reference leaky brain syndrome, in which the blood brain barrier fails, allowing toxins to enter the brain. Displayed alongside the paintings are goblets containing resin filled with disease-causing pollutants that we encounter daily, including in food, medications, and cosmetics.

Kapp Kapp’s booth featuring Velvet Other World at The Armory 2022. Image by Annabel Keenan. Several US-based exhibitors also stood out, including New York’s Kapp Kapp, which is participating in the fair’s Presents section that features galleries under 10 years old. Kapp Kapp staged a solo presentation of charcoal drawings by Velvet Other World, an artist duo consisting of Josh Allen and Katrina Pisetti. Using only black, white, and gray, the duo creates ghostly figures in opulent attire and jewelry that explore costume as a way to protect the body while also constructing specific identities. Crisp and piercing, the drawings are transfixing, even haunting.

HOUSING’s booth featuring Nathaniel Oliver at The Armory 2022. Image by Annabel Keenan. Also in the Presents section is HOUSING, whose booth last year won the fair’s Gramercy International Prize. The gallery followed this success with an equally remarkable solo presentation of new narrative paintings by Nathaniel Oliver that expand upon his interest in science fiction, Afrofuturism, Black magical realism, and the mercurial nature of the concepts of truth and fact. His new works depict scenes of figures who appear to be on the precipice of a journey. In one large painting, the figures sit on a dock, possibly waiting as a ship approaches. This new body of work highlights the tension between trusting others and understanding the inevitable human inclination to preserve oneself.

In Albertz Benda’s booth, Los Angeles-based, self-taught artist Devon DeJardin impressed with large, abstract heads painted in crisp, geometric shapes. With shadows to emphasize the three-dimensionality of the various shapes, the faces appear to pop out from the canvas. A fan of art history, DeJardin pays homage to great artists and artworks, including Pablo Picasso’s cubist figures and Louise Nevelson’s abstract relief sculptures.

Devon DeJardin for Albertz Benda at The Armory 2022. Image by Annabel Keenan. Despite seeing thousands of artworks in the span of several hours, I left The Armory feeling surprisingly rejuvenated and ready for more. I knew that with so many collectors, curators, and writers in town for the fairs, it’s expected of galleries to put their best foot forward with exhibitions in their own spaces, so I continued to a few more stops in Chelsea, Tribeca, and the Lower East Side. I was glad to see that the presentations outside of the fair halls are equally remarkable.

One standout show is Lisa Oppenheim Spolia at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, a powerful exploration of Nazi spolia. In many ways a glorified word for looting, spolia refers to the removal and repurposing of architectural and decorative fragments, which historically takes place during conflict. The items and materials taken live new lives in context far removed from their original intentions. Oppenheim’s source material is the Nazi’s own documentation of looting. Rather than try to recreate lost items, she imagines the personal and shared histories represented by spolia.

Alteronce Gumby’s show The Color of Everything at Nicola Vassell Gallery. Image by Annabel Keenan. Nearby, Nicola Vassell just opened The Color of Everything, a solo show of new works by Alteronce Gumby, the first since announcing representation of the artist last month. Made of resin, acrylic, glass, and gemstones, Gumby’s abstract works resemble the night sky and the cosmos. His surfaces draw the viewer in to investigate the unusual materials and subtle textures. Like looking into a telescope to unknown worlds, Gumby’s mesmerizing works spark curiosity and invite meditation.

Downtown, Juanita McNeely: Portraits is on view at James Fuentes, which is noteworthy not just for the art, but also for the location. McNeely is showing not at James Fuentes’ Lower East Side stronghold, but rather in a new space in Tribeca. While renovations will take place later this year and the gallery will officially move in 2023, the show gives viewers a teaser of this new chapter in the gallery’s life. McNeely’s stunning paintings are large-scale, figural, and sometimes grotesque, featuring unexpected and uncomfortable details like distorted body parts, genitalia and demonic creatures.

Also worth a visit is Trotter & Sholer, which just opened a solo show of new ceramics by Derek Weisberg. A Form of Contemplation includes vases, candleholders, and sculptural works that expand upon the artist’s exploration of the human experience, including grief and joy. With these new works, many of which are functional objects, Weisberg invites the viewer to partake in this exploration, creating moments to contemplate as they place flowers, light candles, or simply to meditate on the meaning behind the materials.

The September art fair and exhibition roster has already delivered in quality and quantity. While The Armory Show is only here for the weekend, it has jumpstarted what will undoubtedly be a packed, diverse, and inspiring fall season. It’s safe to say the summer lull is over.

-

From the Editor

September-October, 2022; Volume 17, issue 1 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,As I’ve been saying since the dawn of Artillery (16 years ago now): LA is the most vibrant art city in the country. This isn’t exactly a revelation, so why focus on LA—yet again—in this current issue? Because we felt it was worth revisiting the subject in order to help all the high-end international and New York galleries that are moving here to settle in and feel secure that they did the right thing.

I made a point to get out more this summer and was reminded how exciting LA’s art scene really is. Our recent transplants might be happy to know that we celebrate summer in a big way, with glamorous alfresco galas held in spacious plazas on balmy nights. This season, my art expeditions took me to The Cheech gala benefit in Riverside, a surprisingly quaint and dusty city about an hour’s drive from LA, while Night Gallery held their Sexy Beast Benefit Auction for Planned Parenthood at their newly expanded space. A stage was set up in the spacious outdoor area for the emcee and various comedians; local vendors served duck tacos and vegan croquets, and there was plenty of wine. Both events—filled with mirth (and hopefully deep pockets)—were for worthy causes.

A Cy Twombly exhibition found us at an early evening preview and reception amid the marble and fountains on the Getty Plaza as we sipped wine and watched the sun set over the Pacific. Then there’s always The Hammer. Everyone loves the Hammer openings (sometimes affectionately known as “the Hammered”). The opening celebration was for Andrea Bower’s powerful survey exhibition, which felt eerily prescient and poignant considering that Roe v Wade had just been overturned. However, we were a bit nonplussed by the scene of caterers whisking away the VIP spread promptly at 8 pm when the hoi polloi arrived. Uh, let them eat breadsticks?

Galas and benefits aren’t the only show in town, of course. There are still tons of gallery openings to go to—and drive to, unfortunately. Getting to and from all these events is a huge inconvenience in such a sprawling city. Attending a Getty event means leaving a few hours early, and begrudgingly having to stay sober for the drive back. Going from opening to opening can be a drag—parking counting for most of the discontent. There can be a lot of ground to cover if you want to fit in several openings—and this is the biggest drawback to living in this great metropolis.

I’m sure the new kids on the block aren’t strangers to big cities though, and we’re only too happy to show them around. Our cover artist, Zoe Walsh is interviewed by newcomer Olivia Fishman. Their complex stunning pool painting series seemed apt for a typically sweltering LA September. Contributor Clayton Campbell profiles stalwart local artist Mark Steven Greenfield, whose work continues the much-needed dialog surrounding racial tension. Doug Harvey steps in with a piece on desert artist Daniel Hawkins—his light tower installation is having its fifth-year anniversary. And there’s much more: Ask Babs confronts Larry Clark; our comic-strip duo knock it out of the park with their spoof on LA architecture, plus reviews of summer shows.

So, if you’re new in town, get out there and see LA’s best for the beginning of the art season (check out our Fall Previews). And if you’re not new in town, get out there anyway. Happy Fall Art Season Art Lovers! Aren’t you glad you live in LA?

-

Beautyful Migrations

The Diaspora According to Njideka Akunyili CrosbyNjideka Akunyili Crosby is having quite the year. Her figurative paintings are on the walls of esteemed museums and institutions across the country, often featuring portraits of herself, friends and family. Akunyili Crosby’s unique style consists of painted, drawn and collaged elements that she blends with a distinctive photo-transfer technique. She uses imagery sourced from magazines, catalogs and her own photographs.

Born in Enugu, Nigeria in 1983, Akunyili Crosby grew up between Enugu and Lagos, and moved to the US when she was 16. Now living in Los Angeles, she brings together these varied influences, seeking spaces where they diverge and intersect. Since earning her MFA from Yale in 2011, she has had exhibitions in major institutions nationally and abroad. She received the highly coveted MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship in 2017, and the United States Artists’ fellowship in 2021. Historic, cultural and diasporic references are at the core of her work. She touches on issues that speak to many different people, places and times, all elegantly woven together in layers of visually stunning imagery.

Akunyili Crosby tells personal and collective cross-cultural stories in paintings that are captivating and contemplative. In November 2021, the Metropolitan Museum of Art commissioned the artist to create a wallpaper that has become an exemplary case of how she addresses complex issues. Made for Before Yesterday We Could Fly: An Afrofuturist Period Room, she conceived of Thriving and Potential, Displaced (Again and Again and…) (2021) a gorgeous green vinyl backdrop. The Afrofuturist installation is one of the Met’s “period rooms,”—recreations of domestic spaces intended to be studied as representations of a specific time.

The Afrofuturist Room addresses the history of the land upon which the museum was built. Called Seneca Village, the area was home to a flourishing community of landowners and tenants who were mostly Black. The city seized the land in 1857 to create Central Park and displaced the residents. The new installation recognizes this history and imagines what a period room might look like if Seneca Village had remained. In doing so, the room shifts from the tradition of focusing on one specific time and celebrates the African and diasporic belief that the past, present and future are connected.

Embracing the layered history told through the installation, Akunyili Crosby’s wallpaper includes images of an archival map of Seneca Village from 1856, which are blended with 19th century photographs of Black New Yorkers, as well as contemporary African diasporic representations. Weaving through these images are verdant okra plants, a crop with significant history as it was carried along with enslaved people through the Middle Passage from Africa to America.

As is common with Akunyili Crosby’s large-scale installations, the wall-paper was originally created as a painting on paper. Previously unseen publicly, the painting is now included in the artist’s current solo exhibition at the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas. Just four works make up the show, all of which were made during the pandemic, giving a glimpse into the artist’s life at home in Los Angeles.

Dwellers: Native One, 2019 © Njideka Akunyili Crosby, courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro, and David Zwirner, Photographer: Jeff Mclane These new works underscore Akunyili Crosby’s interest in plants, including the aforementioned okra. Having studied biology in college and grown up with parents heavily involved in science and academics, she often features the natural environment in her work. In addition to the painting now adorning the Met’s wallpaper, the other three works in the Blanton show focus closely on plant species found both in Los Angeles and Lagos. The largest work is Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens (2020), a self-portrait holding her young child on a porch surrounded by plants. The artist looks straight at the viewer with calm, assured and loving eyes. Her child wears a shirt adorned with the words “black is beautiful.” The pair are a ideal representation of the relationship between mother and child.

Returning to her alma mater, Akunyili Crosby’s work will also be the subject of a solo show opening in September at Yale University’s Center for British Art. The exhibition is the third and final in a series curated by Pulitzer Prize–winning author Hilton Als. The show focuses on her ongoing series The Beautyful Ones, a reference to the debut novel of Ghanaian author Ayi Kwei Armah from 1968. Titled The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born, the novel follows a man as he navigates postcolonial Ghana in a formative period of unrest, loss and political awakening. The series, begun in 2012, features portraits of Nigerian children from her family photographs, as well as images she took on trips to Nigeria.

In addition to her work as an artist, Akunyili Crosby is a dedicated climate activist. She is a founding member of the Environmental Council at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, the first of its kind for a major art museum in the US. The council provides funds for the institution’s commitment to carbon negativity and carbon-free energy and supports exhibitions and educational programs that address climate, conservation and environmental justice.

In another large-scale installation, Akunyili Crosby showed her support of climate activism by contributing to the visual campaign A Cool Million. Founded by three artist-led collectives: For Freedoms, Art + Climate Action and Art into Acres. The campaign launched in April and turned pieces by leading artists into large-scale public works that were displayed on billboards and in museum spaces across California. The goal of the initiative was to raise climate awareness and funds for the conservation of one million acres of forest that is crucial to supporting the state’s hydrological system. Her work, Dwellers: Native One (2019), was transformed into a window vinyl for the Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD) in San Francisco. The installation, on view through mid-September, features lush, dense plants indigenous to Nigeria layered with photographic transfers of the artist and her sister in their ancestral village, as well as an image of a woman advertising African wax-cloth fabric.

In January of 2023, Akunyili Crosby is set to kick off the exhibition program for David Zwirner’s new Los Angeles outpost. As LA begins to feature more of her work, she celebrates the similarities and differences between her African heritage and new home.

Visually stunning, captivating and laden with significance, she always tells complex, transnational stories and underscores the beauty of embracing multiple cultures.

See more of Akunyili Crosby’s work upcoming at Yales Center for British Art, then showing at The Huntington Feb 15-June 12, 2023.

Info: https://britishart.yale.edu/news-and-press/announcing-hilton-als-series-njideka-akunyili-crosby -

Racial Reckoning

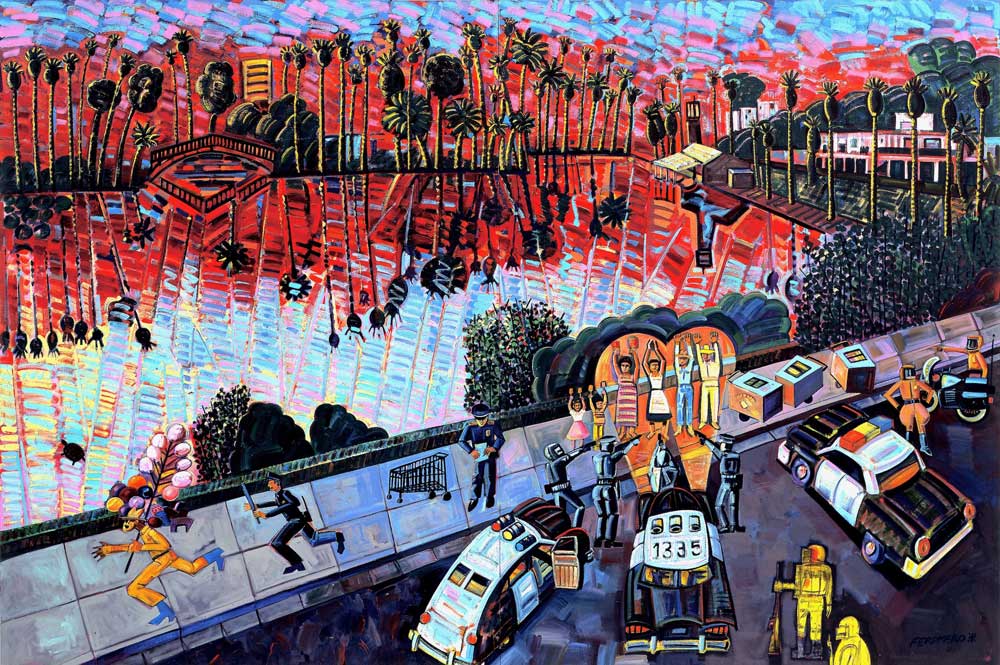

Mark Steven Greenfield Illuminates the Black ExperienceIn 2020, Mark Steven Greenfield unveiled a new body of work, “Black Madonna,” followed by “HALO” in 2022, both at the William Turner Gallery in Santa Monica. Gallery owner William Turner told me in an email that the “Black Madonna” show was a natural progression of Greenfield’s career of investigations into race and racial identity. “It was a sensation when we opened it in the fall of 2020,” Turner says. “It was purely coincidental, but after the summer of George Floyd and Black Lives Matter, our show became a catalyst for people discussing these issues.” Turner witnessed viewers staying nearly an hour in the gallery studying Greenfield’s intricate paintings. “We have never had a show that had that kind of depth of impact.”

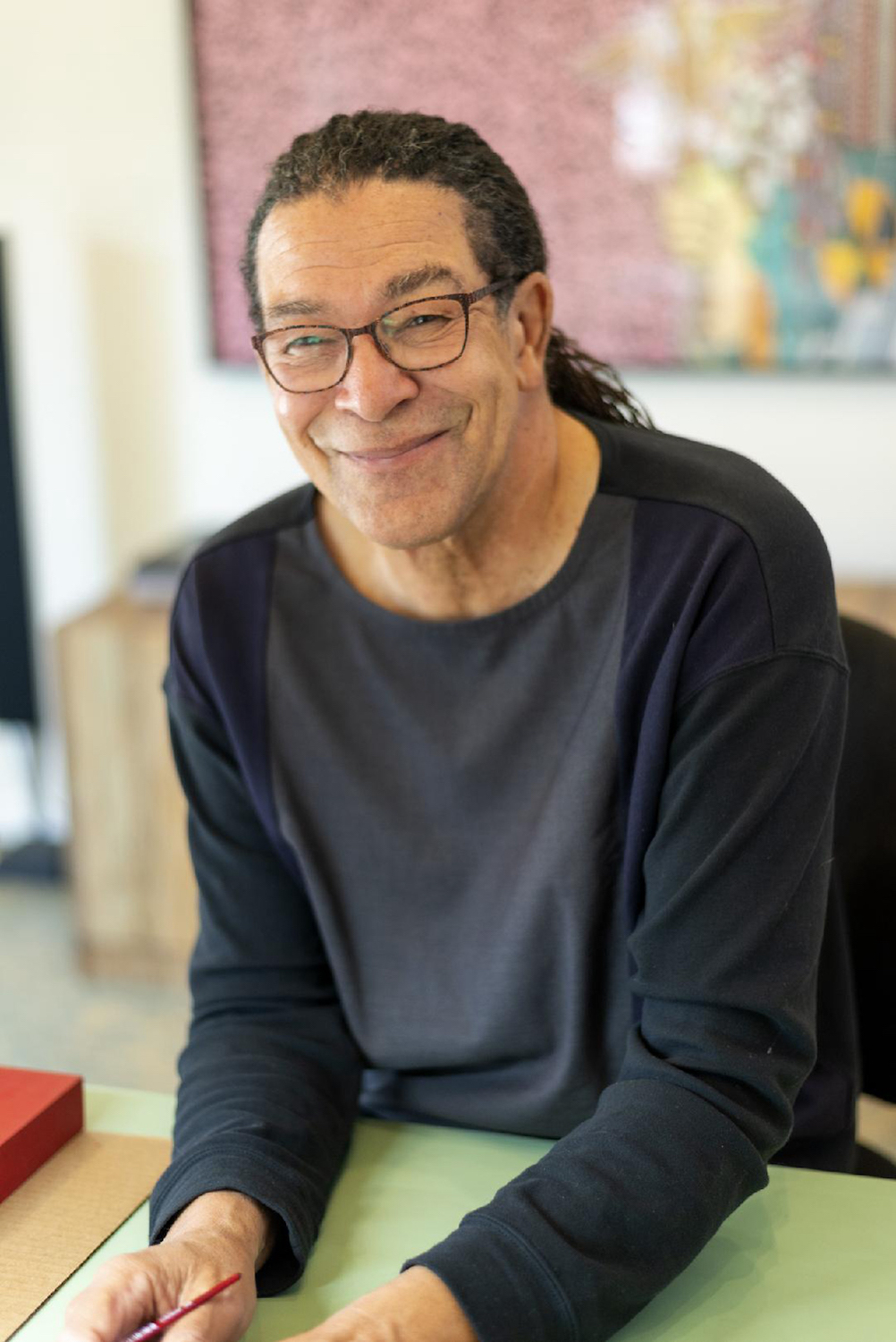

Mark Steven Greenfield Portrait, Photo Credit Tony Pinto A native Angeleno, Greenfield is receiving well-deserved recognition. Besides being a full-time artist, he has had an

extraordinary career as a significant cultural producer in the roles of arts administrator, curator, juror and teacher in Los Angeles. Like many artists who have a hybrid career in the arts, Greenfield worked as Art Center director at the Watts Towers Arts Center and director of the Los Angeles Municipal Gallery for the Cultural Affairs Department, City of Los Angeles. His associations with over 25 cultural and service organizations are a testament to his ethos of service and support for artists and community.

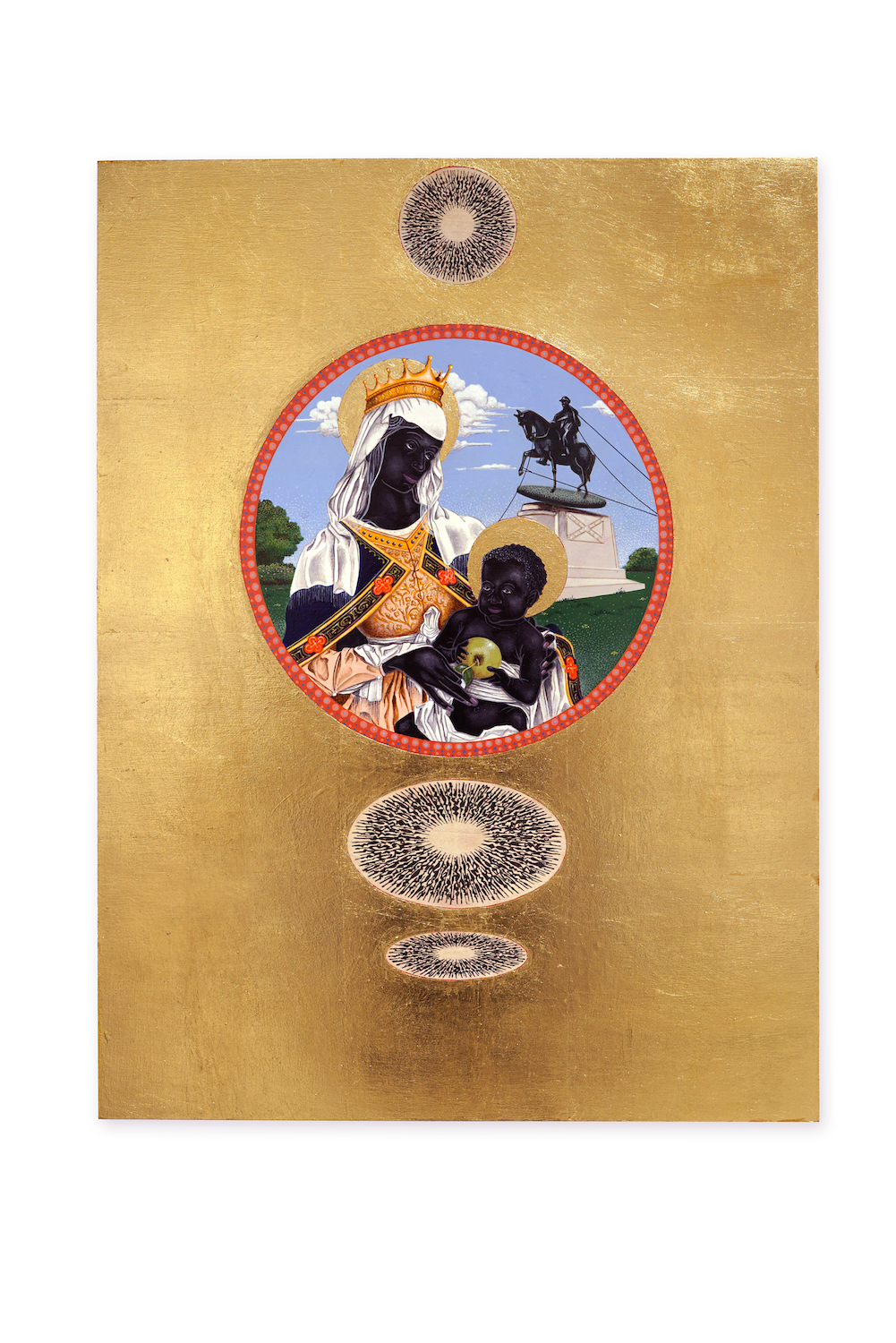

Toppling, 2020, Acrylic and Gold Leaf on Wood Panel, 24” x 18” Raised a Catholic and a long-time practitioner of meditation, Greenfield infuses his work with allusions to ritual, ceremony and spirituality. Painting images of Black and brown persons on gilded panels in a meticulous narrative, representational style, “Black Madonna” and “HALO” become symbols of empowerment and unification. When Greenfield alludes to the protective and healing purposes of traditional religious icon art, he suggests his work is also meant to offer similar forms of protection. Both his series clearly respond to the killings of African Americans by the people who are supposed to keep our communities safe. Greenfield says of his recent paintings that they “conjure up memories of the church and the reverence once paid to statues and images of saints,” but are now redirected to those who have taken up the struggle for social justice. He adds, “I made the choice of honoring those little known heroes, martyrs and personages from whose stories we might gain strength.”

Escrava Anastacia, 2020, Acrylic and Gold Leaf on Wood Panel, 24″ X 24” Greenfield’s art practice explores and illuminates the Black experience, focusing on the effects of stereotypes on American culture. Always provocative in an unexpected way, his work stimulates a much-needed and often long-overdue dialog on issues of race. His recent summer exhibition, “HALO,” has created another conversation. While “Black Madonna” played with the idea of role reversals—revering and worshiping a Black Virgin Mary and a Black Baby Jesus as symbols of love; what if white supremacists were the victims instead of the oppressors—“HALO” evolved as a next natural progression, highlighting historical Black figures. They have been chosen from the period of the slave trade during the 1400s–1800s. He wants his subjects—often legendary in their time yet now overlooked—to be rediscoverd. Greenfield’s use of gold as a material connotes value and importance, but also currency. Most of the people depicted in the series were enslaved and treated as commodities. His figurative painting is particularly striking. Greenfield explains,“The figures are rendered in ‘ultra-black’ in keeping with their political designation and not so much for their degree of melanin. It is the element in these paintings that unifies, regardless of association, wealth, class or prestige.” Almost all of the paintings have circular glyphs, a visual device that is a through line in much of Greenfield’s work. These evoke the mantras he uses as a vehicle in his daily meditations.

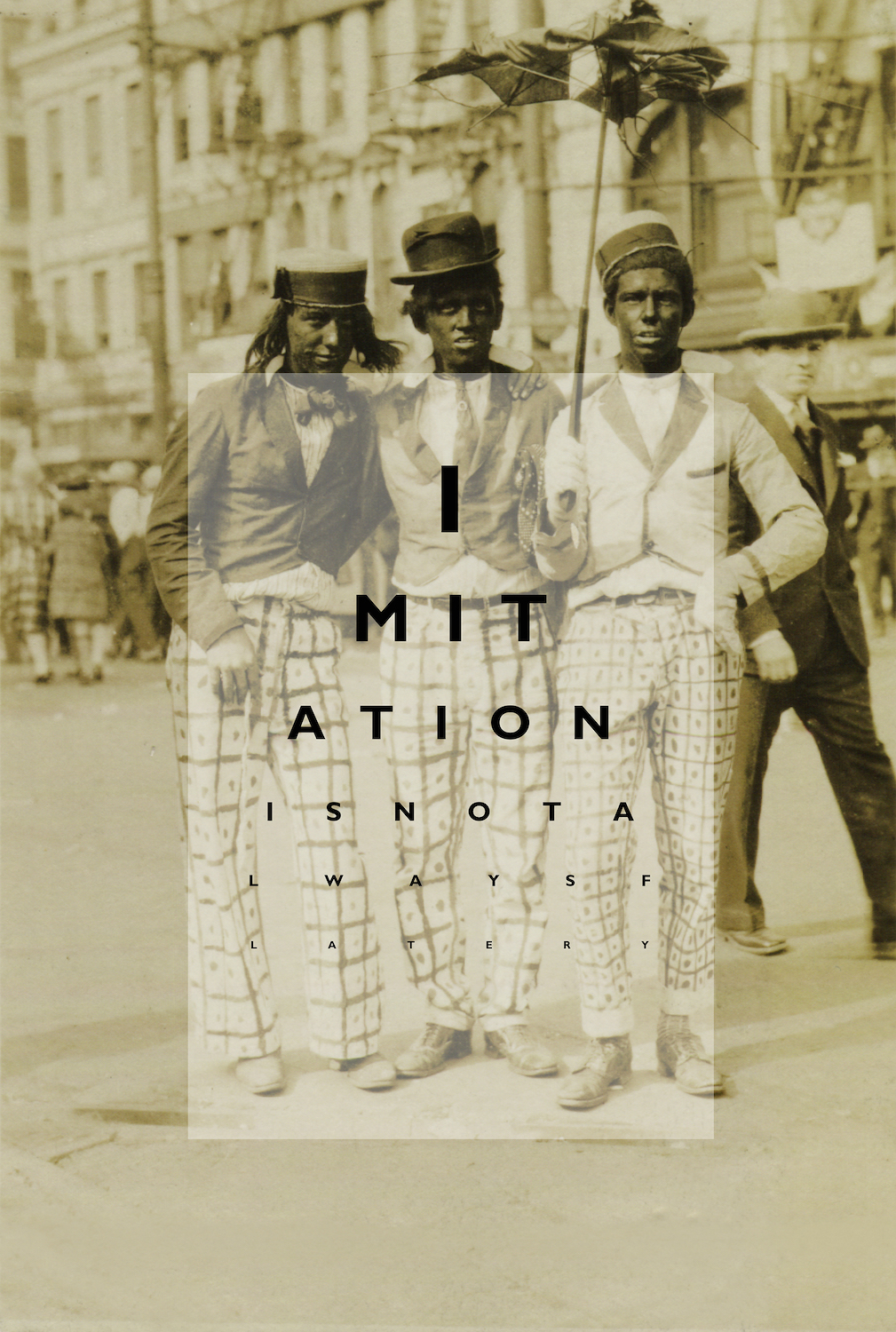

Lesson, 2002, Ink Jet Print, 37″ X 28″ In Greenfield’s work, each series has developed its own stylistic approach. For example, his 2007 exhibition “Incognegro,” at the 18th Street Arts Center, consisted of appropriated photographs. They are mainly of white people in black face, who in turn were appropriating African American culture. For this body of work, he made Iris prints and lenticular photographs. The mirror effect of lenticular photography heightened Greenfield’s intention to expose and dramatize the complexities surrounding issues of race, identity and perception. With the photos of turn-of-the-century black-face performers he superimposed a subversive message that looks like a optometrist’s office eye chart. They contain direct, challenging statements and questions about race and identity. “Incognegro” caused a stir about the use of Black stereotypes and whether they were helpful or hurtful. Mark says of this experience, “Work dealing with the indignities associated with black face has always been a messy proposition.” He believes that black-face images have haunted communities of color for a long time. His intention with this series was exorcising the demons that these images have conjured up; without that, he says, “We’ll never really be free. “Incognegro,” while problematic in 2007 for some segments of the Black community, is starting to impact whites, compelling some degree of introspection on their part. It has brought into focus the responsibilities associated with social justice and allyship. Both “Black Madonna” and “HALO” expand this conversation and engagement with a larger audience that is willing to listen and learn from the social reckoning occurring globally and locally. At a moment when many younger artists of color are gaining national attention for their identity-based work, Greenfield has always been creating conversations about racial reckoning, both as an artist and cultural producer. His unswerving commitment to self-examination and community has made him a change-maker in the best sense of the word.

-

Let There Be Light

Daniel Hawkins’ Desert Lighthouse Turns Five“It looks like the unlicensed pot farms have ceased operations.” Daniel Hawkins is surveying the Mojave Desert landscape surrounding the hill on which he built a fully functioning 50-foot solar-powered lighthouse in 2017. Below us, an elaborate compound of white tents has begun to disintegrate. “There’s another over that hill, but it’s gone too. Maybe the sheriff came by.”

It’s a relief on several counts—for one thing, the pictorial aspect of Hawkins’ Land Art installation will return to its Minimalist default—with the remains of the town of Hinkley (think Erin Brokovich) the only filigree on the horizon. Secondly, reports of ominous dark-tinted high-end off-road vehicles monitoring the activities of Desert Lighthouse pilgrims have pretty much evaporated.

Still, it’s just another aspect of the peculiar theatrical narrative layer the DL has generated over its first five years. Several vloggers specializing in oddball travel adventures have stumbled on the site—“Death Valley–based adventuress and explorer” Wonderhussy is a standout. “The beacon from this lighthouse,” she observes in her YouTube critique “made me feel weirdly safe.” Other locals have developed theories ranging from UFO landing pad signal to PG&E toxic groundwater plume warning to secret government marker of where the post-apocalypse coastline will be.

Desert Lighthouse at night, 2017 A poignant memorial to a local young woman popped up at one point and is still occasionally maintained. “I guess she used to just like hanging out here,” says Hawkins, “and when she died, her church wanted to do something special.” The nearby Fort Irwin military training center strangely recommends a trip to the DL as an edifying use for soldiers’ free time. Then there’s the Stargate Hinkley group, who seem to sincerely believe that ancient astronauts left the lighthouse as a calling card in the long-ago pre-COVID times. About the only crackpot community that hasn’t noticed the Desert Lighthouse is the mainstream art world.

That could all change in October, when PRJCTLA hosts “Desert Lighthouse: V,” the latest in a series of DL-themed solo shows that include Hawkins’ MFA thesis show at UC Irvine, and a spectacular museum-scaled show at the UC Riverside Culver Center for the Arts. But DL:V is the first show since the lighthouse was actually erected. Hawkins, a quintessential postmodern multimedia artist, will include sculptures, paintings, photographs, film and video, etchings, holograms, modified lighthouse detritus, and two publications—one, a catalog of the show; the other a compendium of the byzantine paperwork that had to be completed to make the lighthouse happen. Oh, and possibly some chartered bus trips from Downtown LA out to the Hinkley site.

“I have to repair all these missing panels first,” says Hawkins, squinting up at the towering steel and plastic edifice, “and make sure the fresnel’s [an led lens] working properly.” With his longish hair, glasses and survivalist desert clothes, Hawkins can resemble a central casting rendition of a ’70s land artist, albeit one who has invested money, energy and more than a decade of his life into the realization of an image that came to him in the middle of an agoraphobic panic attack while speeding through the trackless void of the I-15 outside Barstow. “If only there was a lighthouse!” he thought. The rest is history.

Makeshift memorial created by visitors at the Desert Lighthouse, 2019 Not that Hawkins hasn’t been working on other projects. Since completing the lighthouse, he’s produced public sculptures, experimental music and films—while incrementally whittling away at several major works. There’s the long-gestated piecemeal actual-size replica of the Hoover Dam. Then there’s the Radical Mountain project, which sometimes manifests as an exercise in sociological esthetics—basically starting a cult to man an expedition to scale a topographically flat mountain somewhere in Nevada.

At other times Radical Mountain is identified as a fictional mountain-climbing adventure movie—with a seemingly endless proliferation of spinoffs, including a quasi-documentary detailing Hawkins’ extended, absurdist campaign to get actor Val Kilmer involved in the project. In his spare time, he’s collaborated with LA artist Marnie Weber on her last several film projects, and curated her recent survey “Unreal Paradise: Collage Works from 1992 to 2022.”

All the while he’s kept the Desert Lighthouse burning. As the high desert wind picks up and the sun sinks below the richly mottled horizon, he takes a last look around. He’ll be returning over the summer, braving the 120ish temperatures to get the lighthouse back in pristine condition. “I’d be really happy to get some kind of art institutional recognition for the Desert Lighthouse,” he admits, “But the really important thing is that Wonderhussy feels safe.”

Desert Lighthouse: V

PRJCTLA

Oct. 1–Nov. 5, 2022

Opening reception: Sat., Oct. 1, 3–6 pm

Photos by Daniel Hawkins

-

Layering Subjectivity

Q&A with Zoe WalshZoe Walsh is a Los Angeles–based painter originally from Washington D.C. They received their BA from Occidental College and Masters from Yale University. Represented by M+B Gallery, Walsh has exhibited their work in group shows around the world. In 2019, they were nominated for the prestigious Emerging Artist Grant from Rema Hort Mann Foundation and were the Al Held Foundation Affiliated Fellow at the American Academy in Rome in 2015. I asked Walsh the following questions to gain a better understanding of their artwork.

ARTILLERY: I know you studied under Linda Bessemer during your time at Occidental College. To me, there is a connection between how each of you experiments with paint. Can you comment on this?

ZOE WALSH: One link between Linda’s practice and my own is that we each construct paintings by stacking discrete layers of paint on top of and adjacent to prior layers, which is an approach that owes a lot to printmaking logic. The gestures of making are distributed through technologies ranging from squeegees to screens and spackle knives. Linda’s playful and rigorous exploration of the plasticity of acrylic paint is a continued source of inspiration.

Walsh in their studio, photo by Isabel Osgood-Roach In your early work, you incorporated images from Westerns and action films. Now you draw photos mainly from adult films. What contributed to this shift in subject matter?

A common thread from my very early work to my current work is my interest in using spectatorship to talk about dis/identification and desire. While pornographic images are interesting to me because they evoke complicated physical questions, I think the more intentional shift I’ve made is towards using material produced by and for queer people. As a result, I am more emotionally engaged with the complex set of issues that come up over the course of a long project.

A central theme of your work is queer subjectivity. When someone comes across your paintings, how do you hope they interact with them?

I hope that viewers spend time with and get close to my paintings and that each viewer brings their own subjectivity to their experience of my work. I believe that the dialogue that art can generate is transformative. Regarding queerness, it’s so rewarding if my paintings open up space for a viewer to recognize themself in the work.

Zoe Walsh, Knuckles on the equinox, 2021 , acrylic on canvas-wrapped panel , 48 x 48 inches I am immediately struck by the vibrant colors in your work. You use color in an obscure manner. Can you describe what thought or system goes into choosing colors for a piece?

One of the guiding color principles for my series of pool paintings is to work towards the quality of light that exists during the transitional hours between day and night. Those times when the contours of one’s body and the distances between yourself and another are more difficult to discern. A super-bright passage in a painting might not clarify, but dazzle and disorient.

Zoe Walsh, Lost Stars, 2020, acrylic on canvas-wrapped panel , 48 x 48 inches How does technology play a role in your practice?

I use digital technology such as Blender, Photoshop and Illustrator to develop compositions and then employ screen printing to print the first layers of each painting. My process entails shuttling back and forth between the analog and the digital as I develop each piece with additive layers of stencilled acrylic glazes. The paintings that emerge from this exchange reveal a hybrid form.

-

CHEECH MARIN’S NEXT MOVE

An Explosion of Chicano Art in RiversideHow apt that the new Cheech Marin Museum for Chicano Art and Culture in Riverside, California should open in a repurposed public library. Libraries are historically accessible spaces for learning and intellectual research. Museums, on the other hand, still struggle to make themselves approachable—not to mention equitable. Not so with The Cheech, as it’s affectionately known.

“I first learned about art in a public library,” says the namesake collector Marin over a Zoom call: “It was part of a family assignment.” This new visual “library” resonates with a vibrant urgency unlike any other museum in Southern California. The Cheech—an adjunct of the Riverside Art Museum and housed in an understated mid-century building—outwardly belies the permanent collection and rotating exhibitions that it now houses. Since its opening it has been hosting 2,000 visitors a day, virtually at capacity

Marin, the actor and comedian known for his marijuana pranks in the infamous Cheech & Chong films with former partner Tommy Chong, is animated and enthusiastic during our Zoom call. By the mid-’80s, he tells me, “I was beginning to make money.” The first works he collected were three small paintings by Frank Romero, Carlos Almaraz and George Yepes—and the buying continued with a vengeance. Figuration is a hallmark of the collection; he collected what he liked—not as an academic exercise, but rather as an attempt to raise awareness of the Chicano art narrative. Over time his trained eye acquired some masterful works, and the collection now reads like an essential who’s who of Chicano artists—admittedly with some gaps. But this doesn’t pretend to be a historical narrative, or an all-encompassing survey of Chicano art. Marin is considered the foremost collector of the genre. He has amassed over 700 works and continues to acquire more.

Ever malleable, the definition of Chicano is born out of the activist period of the 1960s. Not confined to California, the movement and concomitant art was also notably manifested in Texas and New Mexico, as well as other states. Scholar and artist Dr. Amalia Mesa-Bains observed: “The DNA of the Chicano term—social justice—is still embedded in its meaning and, while there is no conclusive definition, it remains more relevant and expansive than ever. The museum has propelled ‘Chicano’ back into the forefront—ultimately, it’s American art. I think he [Marin] assembled preeminent representations of the genre.” Cheech amplified this vision, concurring, “Each generation builds on the original intent: Latino, Latinx, Chicanx and others.”

Cheech Marin. Image courtesy of the Riverside Art Museum. The existing Riverside Art Museum had previously mounted an exhibition of Cheech’s collection with a record-breaking public response—something the city and museum leaders, headed by Executive Director Drew Oberjuerge, wisely took note of. They just happened to have an empty library that needed a new purpose. After some negotiations and an offer to house Cheech’s collection—an offer he couldn’t refuse—a public/private partnership emerged. With considerable heavy lifting and fundraising, the renovated library was transformed and completed in a record five years; Marin gifting 500 objects from his collection to the center. The city will assist the museum with ongoing operating funds—the kind of stability that is crucial to a budding institution and support that bodes well for its future.

What’s clear as you walk into the museum is its commitment to the Inland Empire’s (as Riverside County and its surroundings are known) local community artists, who are featured in a rotating display in the breezy ground-floor atrium. During my visit, multi-generational families crowded around the exhibit and lingered while discussing the works with respect and admiration. I can’t think of another museum that’s made its commitment so conspicuous and permanent. The museum’s footprint includes rotating galleries dedicated to 95 works from Cheech’s 500-plus gifted collection. Included are well-known artists Vincent Valdez, Carlos Almaraz and Margaret Garcia—and there are many revelations, such as standouts Jeannette Herrera and Joe Peña of Texas and Carlos Puma of Riverside.

Herrera’s work This is the End (2013) is, as she comments, “somewhat older, but significant; it was done at a difficult time in my life.” The picture portrays the artist’s imminent marital breakup. Preoccupied and unsettled, it is a tableau of an uncertain future. Peña spent time in New York working in galleries and was influenced by Modernist inclinations. His work 1:15am, Final Stop (2016) is an atmospheric painting that has a less dramatic backstory than one might assume. “My wife was pregnant, it was late, and she suddenly sent me out for tacos to the local truck. When I arrived, it was shrouded in darkness—as if hovering in space” says Pena. “It’s important to me to capture these moments of local culture.” The picture is a masterful vignette of mood and light—a kindred spirit of Edward Hopper.

Jeannette Herrera, This is the End, 2013. Image courtesy of the Cheech Marin Collection and Riverside Art Museum. Vincent Valdez’ Great Grandfather (1999) is a self-portrait of pensive memories painted in an emerging classical style—using house paint. The artist is foregrounded with the image of his great grandfather in the background surrounded by cultural icons. “My great-grandfather was an artist and an inspiration. I painted this in my junior year at the Rhode Island School of Design. I was the only Chicano there and this helped me adjust,” says Valdez. These works share moments of human sentience—love, loss, pain, remembrance—the universality of the mortal condition.

A separate installation of Einar and Jamex De La Torre’s retrospective, guest-curated by the Getty Museum’s Selene Preciado, is a sensational visual spectacle that occupies the second floor, a designated display gallery that will rotate Latino/Chicano artists with the next exhibition by Judithe Hernández.

The inaugural opening has already had an impact on National and International art circles. “The response has been immediate and global,” says Marin. As for his continuing collecting aspirations, “There are gaps and I want to fix that.”

Frank Romero, The Arrest of the Paleteros, 1985. Image courtesy of the Cheech Marin Collection and Riverside Art Museum. Artistic Director Maria Esther Fernandez was hired from Northern California’s Triton Museum to head The Cheech’s curatorial program. Her plan includes ratcheting up research scholarship, in-depth presentations of solo artists, and establishing an advisory committee to help craft an art-acquisition strategy. In a recent post-opening walk-through, I asked Fernandez what the key objectives were for this new museum: “Our hope is the center will reflect the complexity and richness of the community which has been historically underrepresented in mainstream cultural institutions.”

She has her work cut out for her: raising awareness at a national and international level, bringing recognition to work that has so often been ignored. Long overlooked by the traditional academic canon and art gallery consiglieri as “folk or marginal art,” Chicano artists’ profiles and viability will be greatly enhanced by the existence of The Cheech.

It’s hard to imagine a more rousing and auspicious museum debut.

-

FALL 2022 PREVIEW HIGHLIGHTS

Get ready for the big 2022 Fall art season. This is traditionally the biggest show of any other time in the art world where most galleries put their best foot forward with their September and October exhibitions. We’ve selected a few highlights coming this Fall in Southern California.

The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA

Judith F. Baca: World Wall

September 9, 2022–February 19, 2023

Museum of Contemporary Art,

Los AngelesHenry Taylor: B Side

November 6, 2022–April 30, 2023

The Broad

William Kentridge:

In Praise of ShadowsNovember 12, 2022–April 9, 2023

The Huntington

Gee’s Bend: Shared Legacy

September 17, 2022–September 4, 2023

Hammer Museum

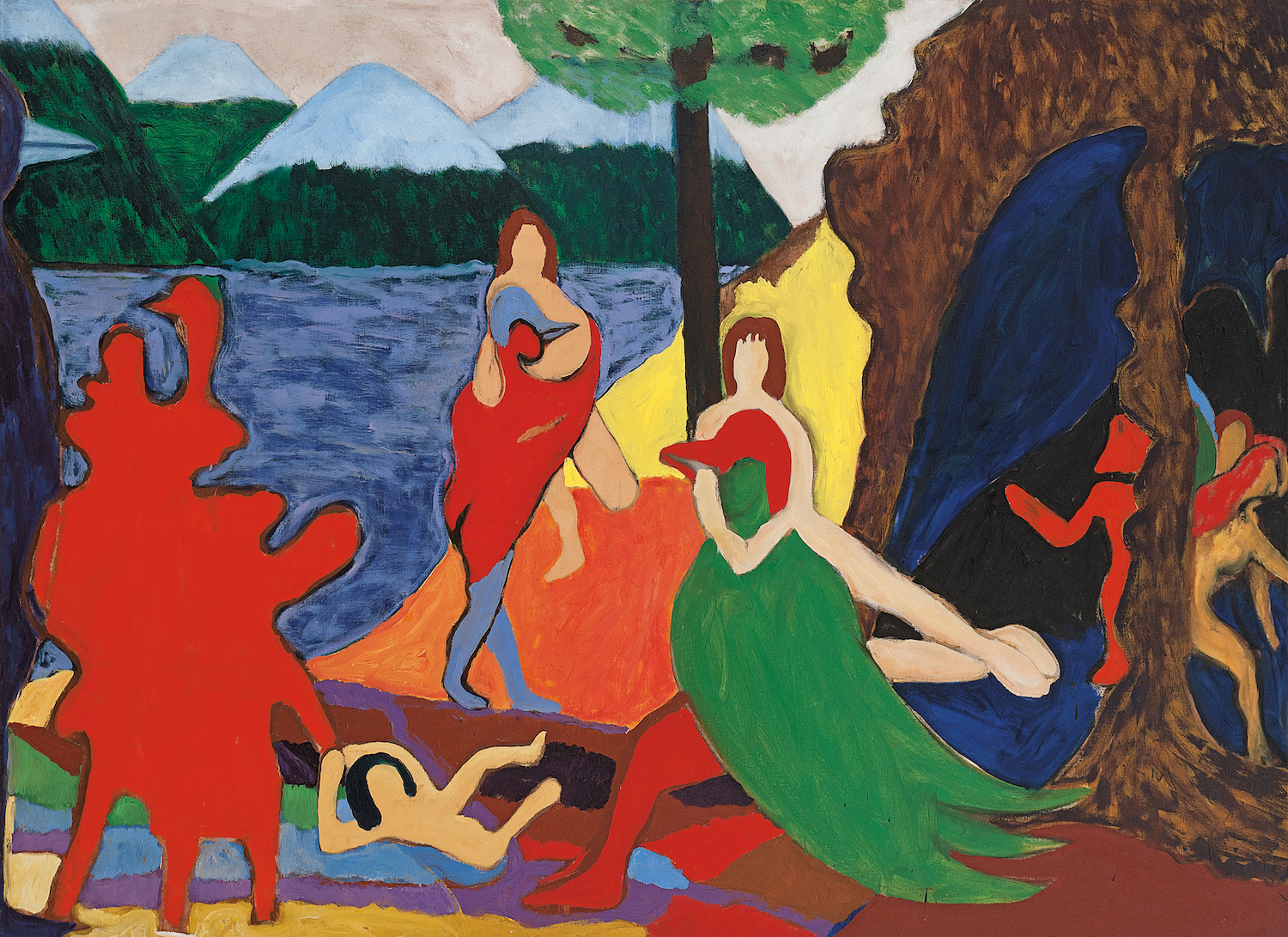

Bob Thompson: This House Is Mine

October 9, 2022–January 8, 2023

Orange County Museum of Art

13 Women

October 8, 2022–October 1, 2023

The Getty Center

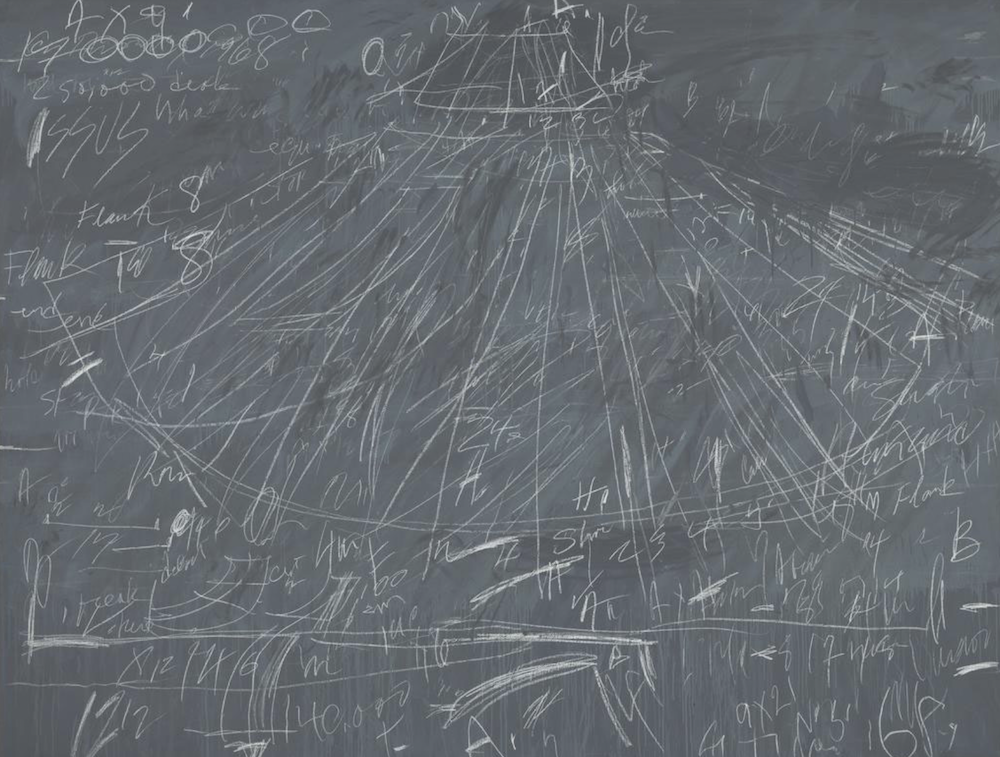

Cy Twombly: Making Past Present

August 2–October 30

USC Fisher Museum of Art

Louise Bourgeois: What Is The Shape Of This Problem?

September 6–December 23

Roberts Projects

Kehinde Wiley

TBD

Museum of Contemporary Art

San Diego in La JollaAlexis Smith: The American Way

September 15, 2022–January 29, 2023

Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles

Cindy Sherman: 1977–1982

October 27–December 30

Sprüth Magers

Nancy Holt: Locating Perception

October 28, 2022–January 14, 2023

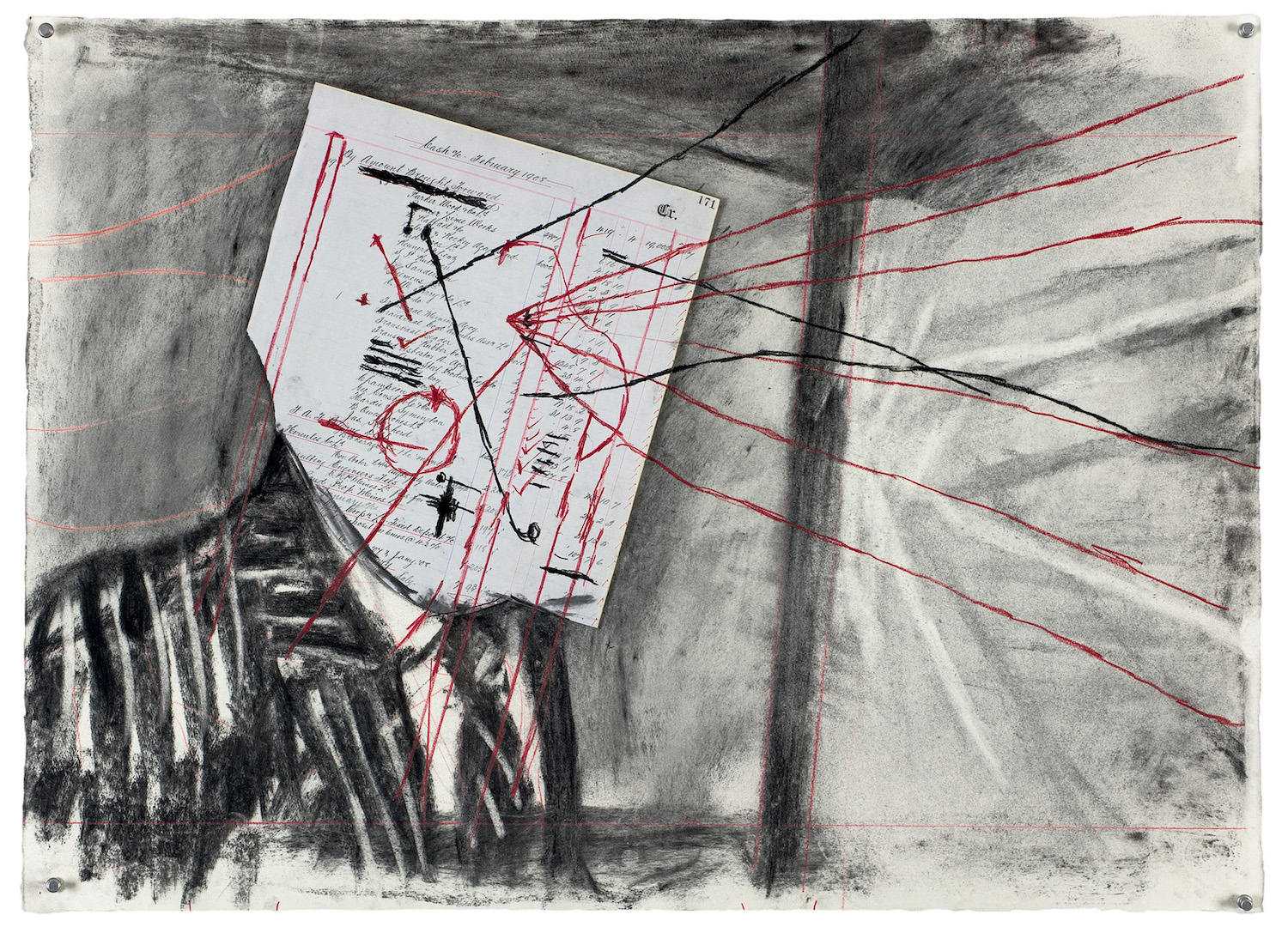

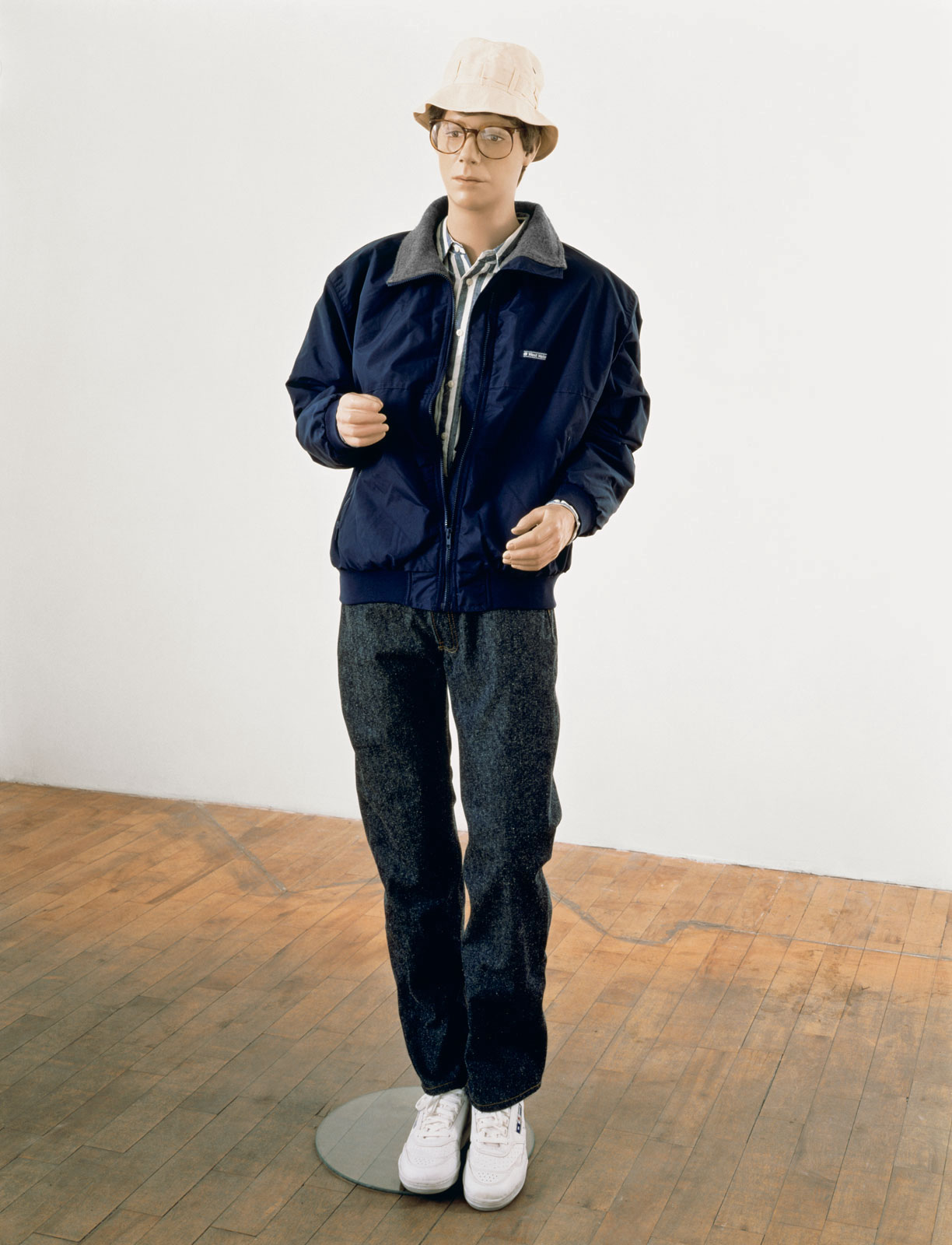

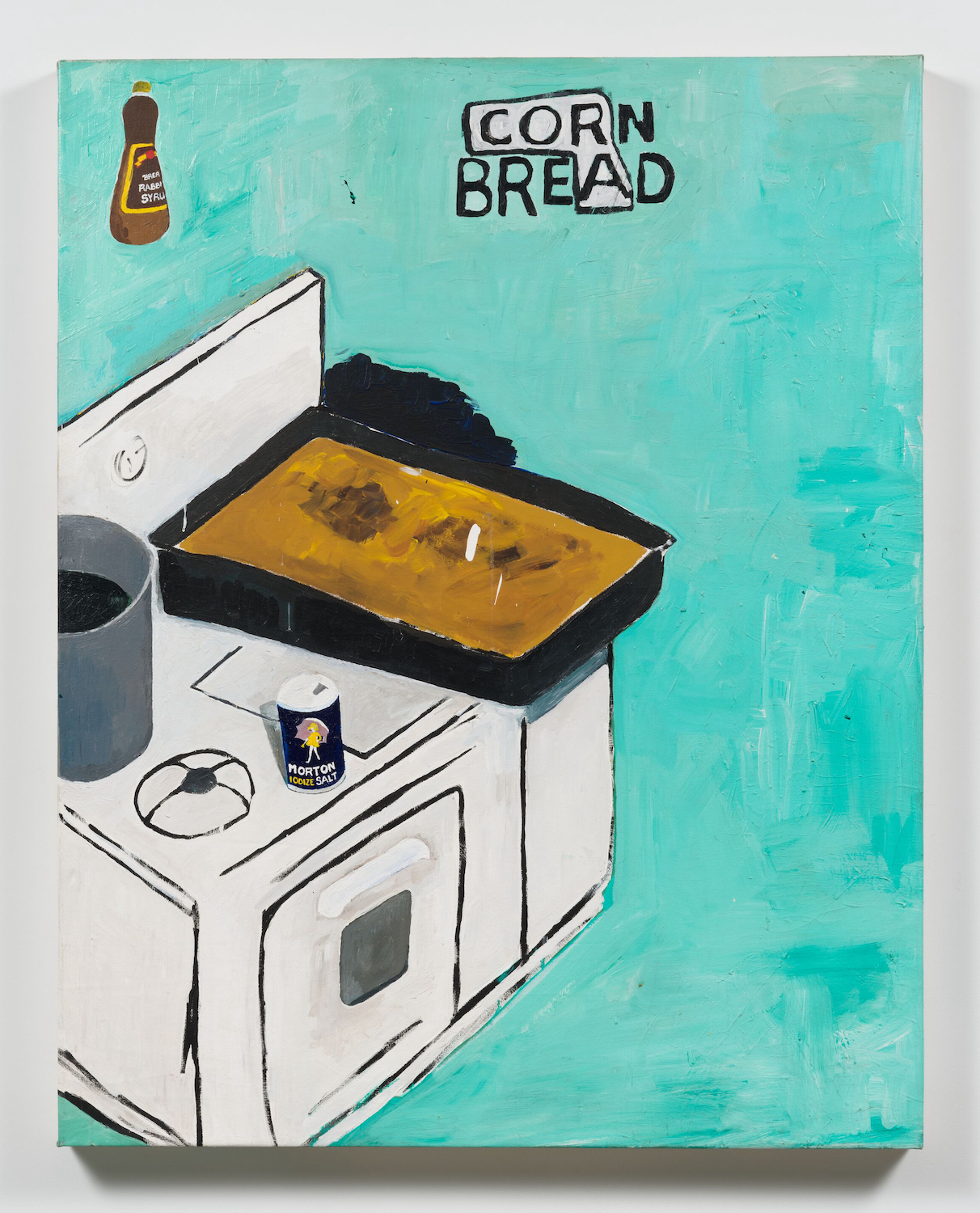

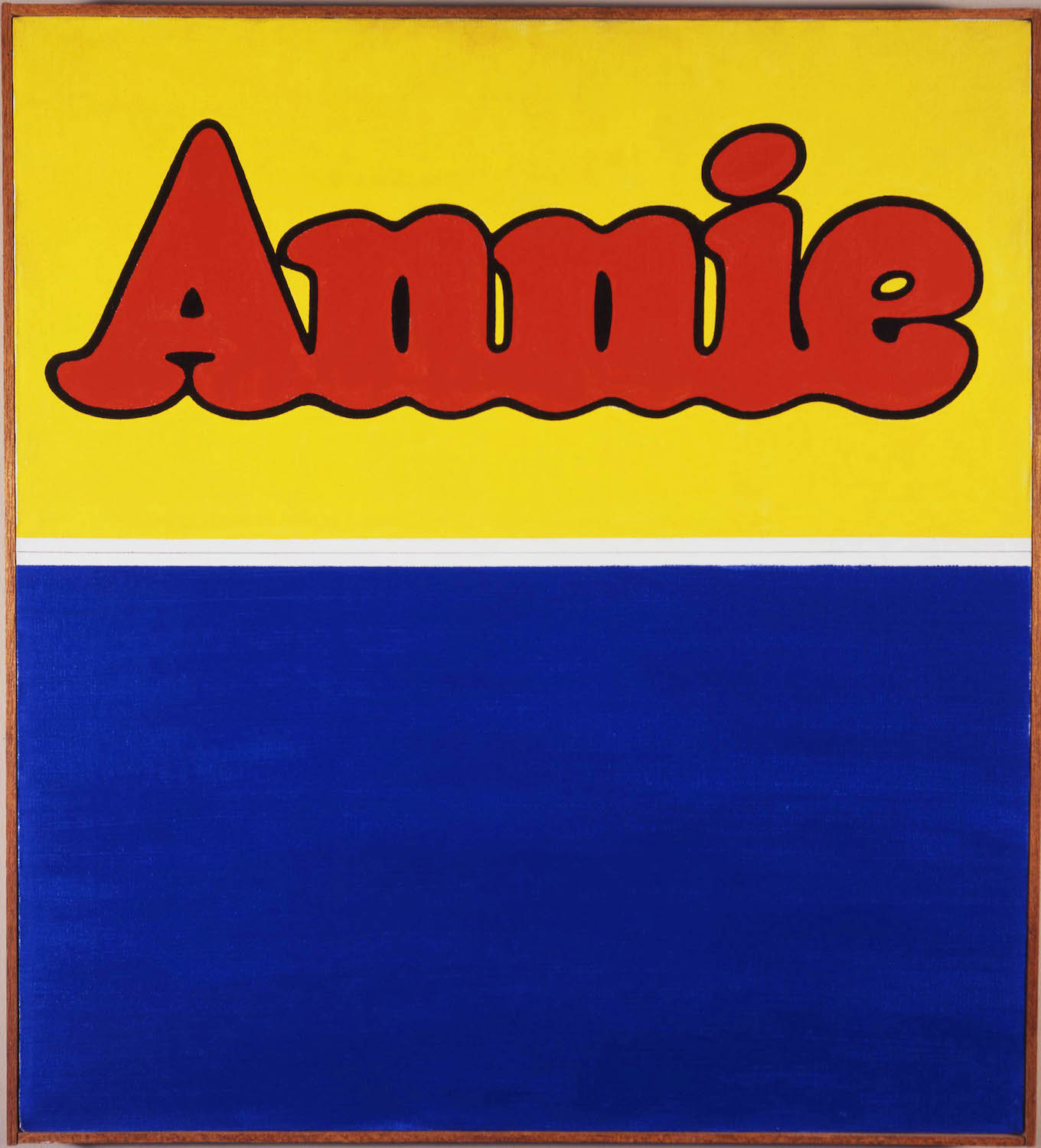

Charles Ray, Self-portrait, 1990. Painted fiberglass, clothes, glasses, hair, glass and metal, 75 x 26 x 20 in (191 x 66 x 51 cm). Collection of Orange County Museum of Art. Museum purchase, 1990.002. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. © Charles Ray. Photo: Reto Pedrini Cy Twombly, Head of Emperor Marcus Aurelius, Roman,about 161–180 CE, marble, 19 5/16 x 11 13/16 x 11 13/16 inches; collection of Twombly Family, Rome; photo by Alessandro Vasari. Loretta Pettway, Remember Me, 2007. Color softground and hardground etching with aquatint and spitbite aquatint, 28 3/4 × 28 3/4 in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. William Kentridge, Drawing for the film Other Faces, 2011, charcoal and colored pencil on paper, 221⁄2 x 31 inches; courtesy The Broad Art Foundation, Los Angeles Henry Taylor, Cora, (cornbread), 2008, acrylic on canvas, 62 5/8 x 49 7/8 x 3 1/8 inches; courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth; photo by Jeff McLane Ed Ruscha, Annie, 1965. Oil on canvas, 21-7/8 x 19-7/8 in (55.6 x 50.5 cm). Collection of Orange County Museum of Art. Museum purchase with additional funds provided by the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency, 1978.011. © Ed Ruscha Bob Thompson, Bird Party, 1961. Oil on canvas. 54 3/8 × 74 1/4 in. (138.1 × 188.6 cm). Collection of the Rhythm Trust. © Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York Cindy Sherman, Untitled, 1981,chromogenic color print, 24 x 48 inches; © Cindy Sherman, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. -

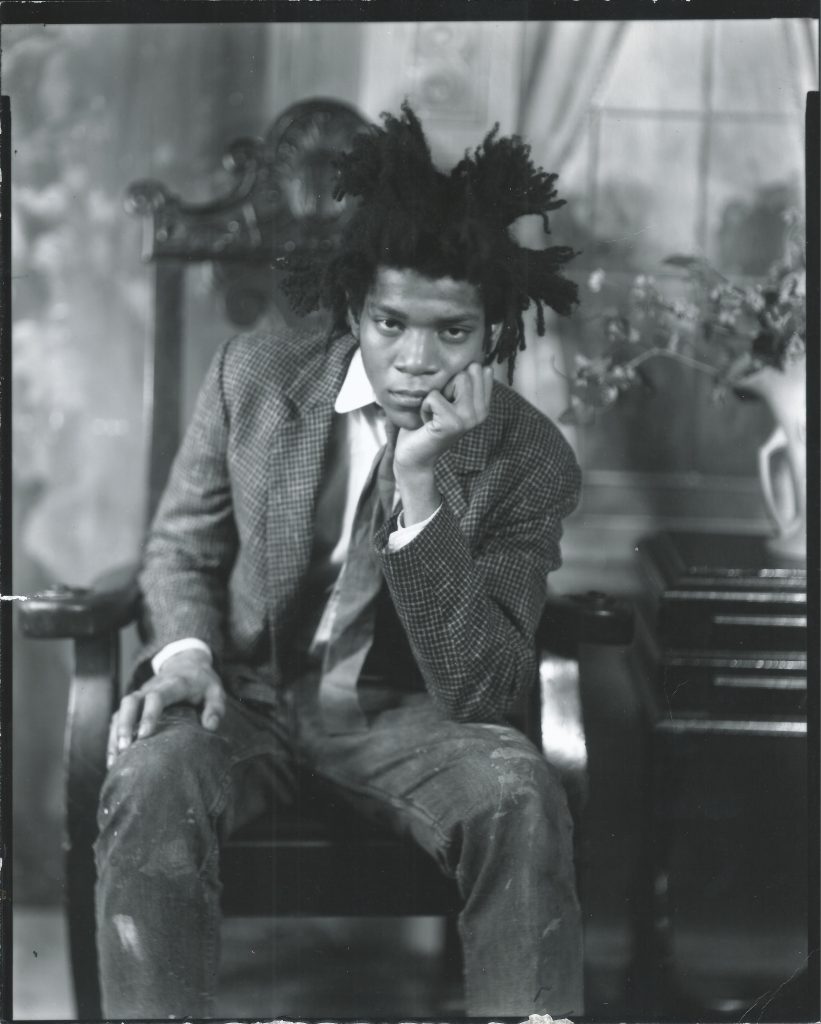

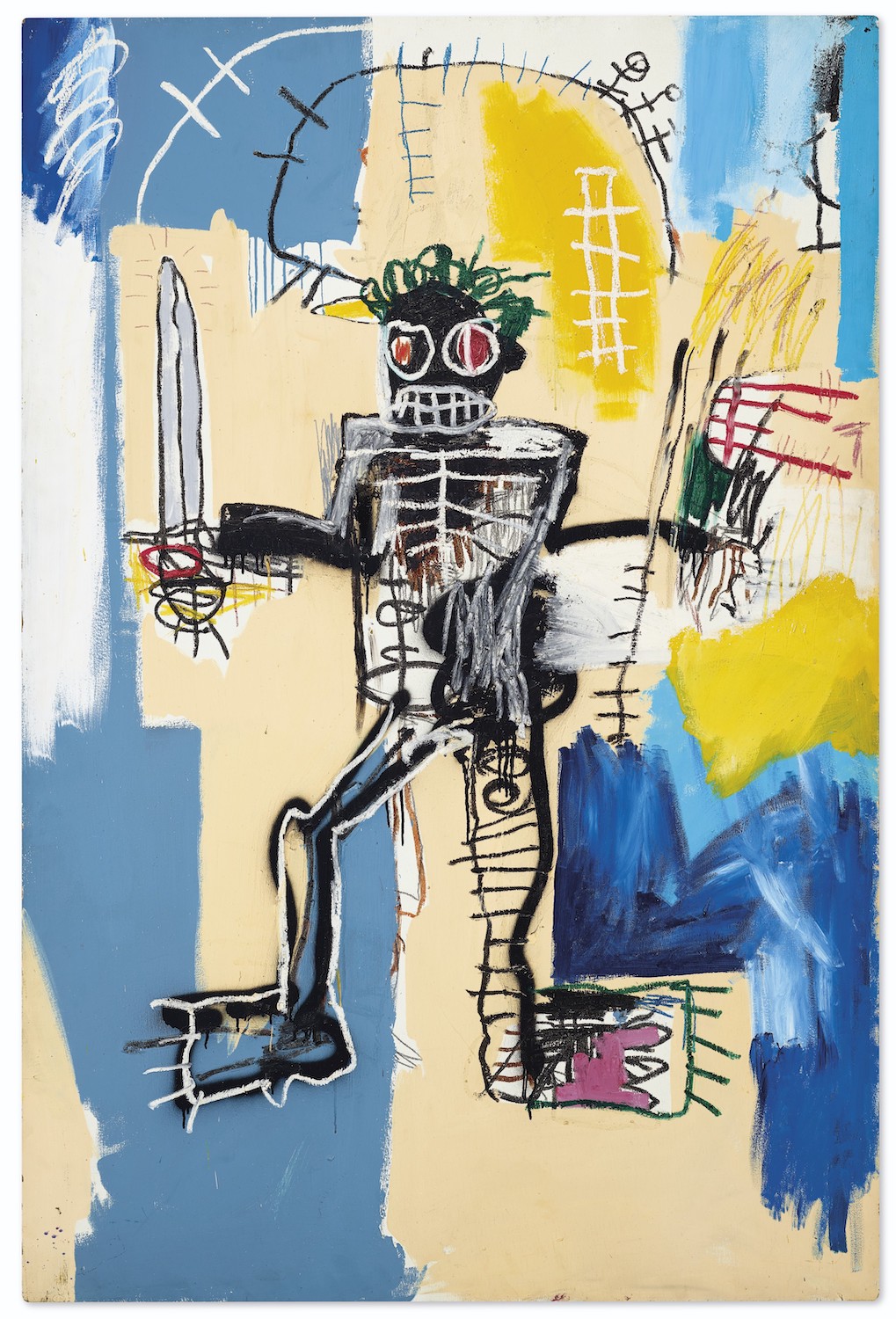

Basquiat Paintings Seized by FBI

Art BriefJean-Michel Basquiat, some say, was an artistic genius. His paintings’ auction values now equal or exceed those of his friend and mentor, Andy Warhol. A couple of top-notch Basquiat shows wowed New York City this past summer, including a major exhibition sponsored by his family members. But it was another show at the Orlando Museum of Art, “Heroes and Monsters,” that is the subject of several meticulous investigative stories by The New York Times, questioning the authenticity of the show’s 25 purported Basquiat works.

Basquiat forgeries have plagued the art world since his tragic death in 1988. The Basquiat Foundation ceased authenticating artwork in 2012 after being dragged into costly litigation concerning issues of authenticity.

I had a firsthand lesson a few years ago when asked by a dealer to assist in finding a buyer for a handful of small Basquiat paintings. I am certainly no expert on Basquiat, and prior to a buyer search I brought in an art consultant, who concluded that the works somehow looked “too perfect.” But it was the stories of their provenance that made me shy away from providing any assistance to the dealer—they were preposterous tales of acquiring the items from Basquiat for what amounted to chump change.

Jean-Michel Basquiat in 1982. Photo: ©Van Der Zee, 1983. The provenance story for the Orlando “artworks” is even more fanciful, including a Hollywood connection. Apparently, we are to believe that Basquiat created these works—all on scavenged cardboard—in a studio below mega-dealer Larry Gagosian’s LA home in 1982 at the time he represented the artist (Gagosian has publically expressed doubts about the veracity of the story). Basquiat then allegedly sold the lot to LA television writer Thad Mumford for $5,000. Mumford (now deceased) supposedly placed the paintings in a storage locker and forgot about them for decades.

The storage unit’s contents were auctioned to two buyers for $15,000 after being seized for nonpayment of rent in 2012. Both buyers have criminal convictions for drug dealing and one of them also had a stock swindle rap in which he was accused of forgery. Well-known entertainment litigator Pierce O’Donnell also got in on the act by purchasing a share in six of the suspect paintings. O’Donnell said he brought in experts who authenticated the work, including one who wrote a book on Basquiat. However, that expert, University of Maryland art professor Jordana Saggese, told the Times nine of the works could not be authenticated.

The story of the works’ genesis would have us believe that Mumford had forgotten about a virtual goldmine in his storage unit—by 2012 Basquiats were selling in the millions at auction! None of Mumford’s friends or family ever heard him say he owned Basquiat artworks.

At least one of the “artworks” was painted on the obverse of a piece of FedEx labeled cardboard. The Times went so far as to consult with a brand expert who used to work for FedEx—and told the paper that the style of the FedEx logo on the cardboard wasn’t used by the company until 1994, six years after Basquiat died.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Warrior, 1982. Courtesy of Christie’s. On June 24, 2022, the FBI raided the Orlando museum and executed a search warrant seizing all 25 of the Basquiat works.

The affidavit of FBI special agent Elizabeth Rivas, attached to the Bureau’s search warrant, is damning. Rivas said she interviewed Mumford in 2014 and was told he never purchased a Basquiat work. The Times reported, “Mumford also told Rivas that one of the artworks’ owners had ‘pressured him to sign documents’ claiming that he had owned the collection…even offering in an email to give him a ‘10 percent interest in the net proceeds.’”

Saggese is also mentioned in the FBI affidavit as having been paid $60,000 for her opinions. She said she tried to get her name disassociated from the exhibition, but was bullied by the museum’s director, Aaron De Groft, to keep quiet.

The owners claimed to have a $100 million appraisal for the Basquiats from Putnam Fine Art and Antique Appraisals. However, it looks like it may be a while before the owners are either indicted, or the FBI returns the “artwork” to them. It’s highly unlikely the suspect “artworks” will ever hang in a museum again.

-

YANOE X ZOUEH’s Massive AR Murals

The DigitalWhat do we imagine when we think about art in the most primal form that it has taken throughout the ages? It is easy to pick out important sculptural works or historic paintings on canvas—but often overlooked is the pureness of paint on a wall. Whether looking back to the age of smearing berries, ash or pigment on a cave wall to the baroque fresco paintings that dominated the Renaissance church walls or contemporary Shepard Fairey graphics on LA building facades, muralistic wall painting has and will continue to dominate large-format art making. The advent of the giant concrete building facilitating urban sprawl coupled with beautifying our urban spaces—plenty of structures exist to be covered with contemporary murals. But how do we actually make those murals contemporary?

Where does our obsession with the digital world overlap into the hard urban landscape? Easy: augmented reality. With the advent of AR and the access we each have to tiny supercomputers in our pocket, a classic wall painting has the potential to be so much more. A handful of muralists and artists are beginning to use these digital techniques, but artistic duo YANOE X ZOUEH is both originator and current world-record holder for the largest AR mural.

While the collective’s name is a mouthful, it echoes the graffiti backgrounds of the two artists, Ryan “YANOE” Sarfati and Eric “ZOUEH” Skotnes, who sharpened their artistic chops as street writers in opposing Los Angeles graffiti crews. Their public art now embodies cooperation and facilitates a global reach.

The two artists now exclusively collaborate to work on a scale that others must struggle to comprehend. Originally setting the record for largest AR mural in the world in 2019 with the 11,000 square-foot piece The Journey in Columbus, OH, the duo has subsequently one-upped themselves during COVID with the new mural The Majestic. Encompassing 15,000 square-feet and wrapping around the façade of the Main Park Plaza garage in Downtown Tulsa, OK, The Majestic stands alone as a formidable art piece in our version of perceived reality.

YANOE X ZOUEH, The Journey, Columbus, OH, (AR). Image Credit: Jessica Miller. Sheer scale and visual aesthetics only scratch the surface of what this artwork is. Take out your smartphone, scan a QR code, and then everything gets interesting as the artwork begins to manipulate the viewers spatial understanding of the world around it. In physical reality we are confronted with this beautiful and dominating structure, but gaze through the phone in any direction and what you see is no longer that. As the first 360-degree AR mural, portions of the art remain in augmented reality, but the world has taken on a Tim Burtonesque feel with the occasional giant catfish passing while the bustle of the street has transitioned to a serene ocean.

During my LA interview, the team mentioned a change on the horizon—an embracing of both the physical and the digital in experimental ways. Painting, AR, digital and physical sculpting—nothing is off the table. The 2021 work Rise Above in Inglewood, CA, began to embrace this transition by introducing digitally produced sculptural elements to complement the painting. Large acrylic components were engraved and cut from computer files and used to cover portions of the mural. They create an aesthetic component and also function as digital lighting to facilitate night viewing of the AR elements of the work.

From what I gathered, this is just the tip of the iceberg of where this duo plans to push their real world/digital world art practice. With a multitude of public works in line that are awaiting formal announcement, it seems likely that we will see some new boundaries being pushed by YANOE X ZOUEH. Will a robot walk out of the mural in AR and trip over a real-world bronze sculptural element, stand up, shake itself off and hand (transfer) you a custom NFT based on the angle of the sun when you scanned the QR code? With these two artists, it doesn’t seem a stretch.

-

13 Ways of Looking at Kayla

DecoderIt can be a disservice to describe an artist whose art describes a constantly changing self.

1. Kayla Tange looking platonically calm, platonically Asian, platonically a performance artist, dressed in an all-white so crisp it might be paper, in a great glass box surrounded by a respectfully quiet audience, surrounded by an unobtrusive low-noise soundtrack, surrounded by an art gallery, painting with a pale wooden-handled brush. Slowly she’s painting the inside of the glass box white.

2. “I’ve straight-up given lap dances on a La-Z-Boy boy that was duct-taped or like they’d say ‘People were murdered outside yesterday’ and you’re just like ‘…cool?’ Back in the day there was a place in the valley called Bob’s Classy Lady. I mean come on, the name alone—so bad but so great! Sometimes I’m like I think I just worked at these places because—well, besides needing the money there was something relatable for me about it. I was equally attracted and appalled by seedy clubs.”

3. Something indescribable. A sculpture, something like a volcano of nail polish and something like a universe forming, impossibly glossy, oozing, unformed, fountaining, very red over a dry white base. Barigongju Entry Ritual, 2021, unfired clay, acrylic. About the size of a saucepan.

4. I’m in the back of the Uber, heading up Vermont, watching her 2017 piece Dear Mother, which is a video-letter to the birth-mother who she never met. Who refused to meet her. I’m crying. Because of a goddamn piece of performance art. On a phone.

5. “I did a show that Luka Fisher and Tristine Roman curated called ‘A Golden Fool’—the cops came, and everyone ran out. I was naked, running across the street, robe barely hanging. It was so fun—‘Remember that time that we were in this warehouse—there were people covered in glitter and jewels jacking off in the rafters, it was wild.’”

6. Children and old people using sticks to draw in the sand filling a white frame on a gallery floor. Each drawn line revealing a glow from underneath because the sandbox conceals a lightbox below. On YouTube, we see Kayla in a could-be-couture arrangement of translucent and artful black-and-white fabric kneeling over, and writing in, her own box; then, in another stylishly asymmetrical outfit, talking about healing. Cello music.

7. Kayla in nothing but a blonde wig and white underwear, winking over an asymmetrically dropped shoulder back at the audience, in a cellphone photo I’ll draw a picture of. That picture will be published in an art book.

8. Kayla in a sky-blue-and-white hanbok framed in front of a window which itself frames a daylist section of a Los Angeles street. Lifting colors from bright upright bottles of yellow, red, purple, etc she smears them on plexiglas while the art audience watches her and also the projection to her left, showing an abstract film of the painting she paints in real time.

9. Kayla as a sex-nun in latex, crawling, collecting anonymous confessions on scraps of paper, which become the raw materials for the next piece.

10. “I have like thousands of confessions,

boxes of them. Like, they’re horrible, I mean like people are talking about like murdering people. Like why do I need that in my house? Do you know what I mean? But it was like I wanted to collect the most I possibly could to develop some understanding of humanity …I don’t know that I could do these pieces again.”11. Something alien and elegant, a figure in a glittering gown, far too tall with a glowing bluish-pale sphere beneath a veil for a head, holding feather fans. There is music from one kind of club, and then a different kind. Before it’s over the creature will reveal itself to be Kayla, again, basically naked. Kayla calls the version of herself who does this “Coco Ono.”

12. “I was like how am I supposed to make objects? I have nowhere to put them, I don’t have space to make them …I found my way into performance from like stripping and stuff because like I just needed a bag of clothes.”

13. “I just feel like: maybe I want to seduce. So why not say something also?”

-

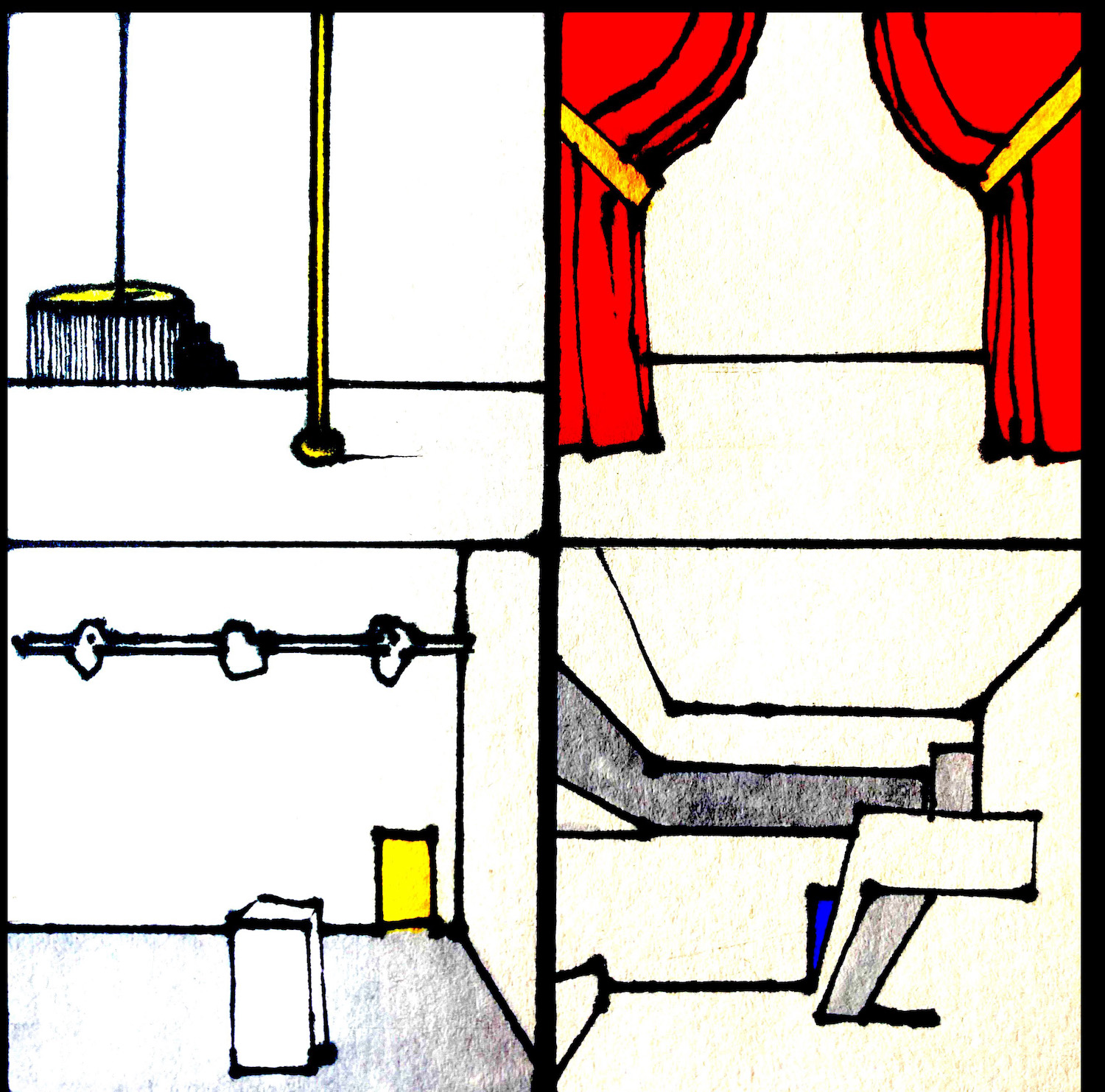

Tableaux Vivants

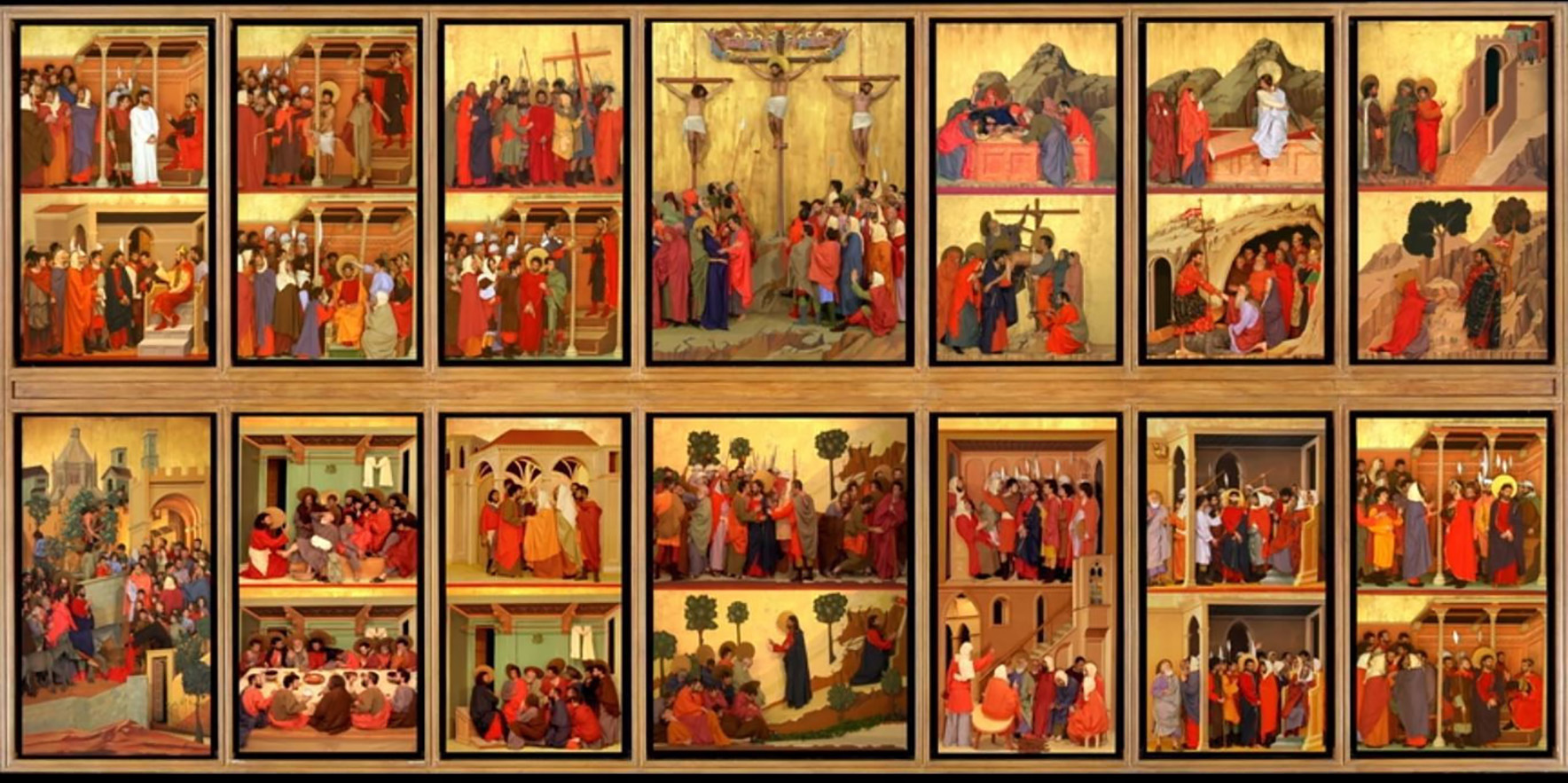

Bunker VisionBack in the days before television, radio and movies, a popular form of entertainment was the Tableau Vivant. People would pose in costumes alongside elaborate props to reenact historical events, or to mimic paintings and statues. If you have ever encountered the Pageant of the Masters in Laguna Beach, you have witnessed the modern-day version. Tableaux Vivants offered a way for people to be onstage without any special talents or having to learn any lines. Over the years films have often referenced paintings, at times only subtly, where it may or may not be intended for viewers to notice. Andy Guerif’s 2015 film Maesta La Passion du Christ takes this concept to the next level.

The Maesta by Duccio di Buoninsegna (1308) is a giant 26-panel altarpiece that portrays the passion of Christ from the entrance of Jerusalem to the road to Emmaus. Any single panel of this work could make for a full evening of Tableaux. The filmmaker recreated the background of each panel on stand-alone sets reminiscent of Japanese screens. The sets are stitched together digitally. Sometimes people will move from one set to another, and in other cases they will vanish when they walk out of the frame. The cast is attired simply in vividly colored tights and black socks, simple tunics and carefully draped pieces of fabric. These actually cause them to seem less three-dimensional against the gilded backdrops. The way that the action moves from one panel to the next might bring to mind players on a board game. By way of anchoring the action, two characters spend the movie in the upper two right hand panels building what appears to be a tomb. Characters will fill a panel with action that looks like a scene being naturalistically acted out. When they reach the moment where the figures match those in the painting, they all freeze in place. Then they carry on the rest of the scene that leads to the next panel.

Once all of the frames have filled and emptied, we are treated to a final look, with all of the panels filled with people interacting, and then frozen in unison. This bookends nicely with the opening scene which focuses on the single crucifixion panel. It is fully acted out before the title appears. In addition to its function as a storytelling device, it gives us a closer look at the details that create the illusion that this is a painting come to life. Without seeing this close-up, look at the details that give the illusion of a painting; one might conclude that what we are watching is some interesting CGI. The precision of the choreography that allows the camera to freeze on a still shot without carefully posing each cast member to match the painting makes what you see look deceptively simple and natural. This would work beautifully as a gallery installation. Watch it on the biggest screen that you have access to.

-

SHOPTALK: LA Art News

Aspen Art Week, Tom of Finland Fest, and moreLonnie Holley Visits LA

One of the best gallery shows this year was the self-taught artist Lonnie Holley’s solo show at Blum & Poe, and one of the hottest tickets was a recent Saturday afternoon talk between Holley and Jane Fonda. That may seem an odd pairing, but as the actor and activist explained at the start, “I lived in Atlanta for 20 years”—that is, when she was married to you-know-who. During that time she met Bill Arnett, a major art collector and supporter of what he called “vernacular art,” art by Black artists of the American South. Through him Fonda met a number of artists, including the Atlanta-based Holley.

Well-prepped of course, Fonda asked astute questions about Holley’s life and work. Holley, in his own elliptical way, often responded by addressing something bigger. He had had a tumultuous childhood, ending up at the notorious Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children, where he was brutalized. Fortunately, his grandmother was able to get him out when he was 14. ”I think I was chosen to go through the whole nine yards to be a witness to the ways of life,” Holley said. Much of his work reflects the poverty and pain he has experienced and seen. Take the series of early sculpture made of a sandstone-like material he salvaged from a foundry; he began to use the material when he had to make a tombstone for his sister’s two young children killed tragically in a fire. Later he created figures of others he wanted to remember or commemorate, including mythical ones. Holley’s assemblage pieces touch on themes of slavery and inequity. “No Negro was given the title of artist,” he says, “but they were creating, creating… When do we get credit for being who we are?”

Holley is getting credit now, being repped by a major gallery (this is their first show of Holley’s work) and featured in The New York Times last year. However, he finds that the world has gotten into a perilous state. “It’s hell that we are facing,” he said.

Lonnie Holley in conversation with Jane Fonda on the occasion of What Have They Done with America? at Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, 2022

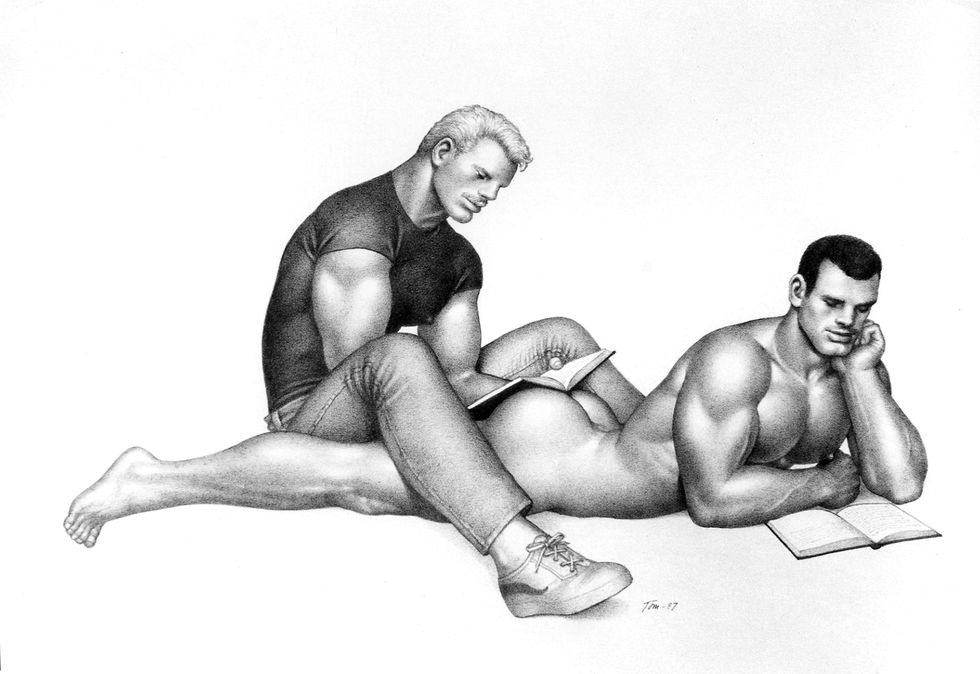

© Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/TokyoTom of Finland Fest

For the first time the annual Tom of Finland Art & Culture Festival takes place both in Los Angeles and in London the same weekend (October 8–9), in Second Home workspaces in both cities. The festival brings together artists, galleries and patrons to network, and to buy and sell works of queer erotic art. Second Home Hollywood has a large garden and a pavilion for art installations, performances and presentations. Second Home Hollywood is located at 1370 N. Saint Andrews Place, while Second Home Spitalfields is at 68 Hanbury Street, London. Get your tickets for single days or the whole weekend at https://www.tomoffinland.org/artfair/

Tom of Finland, Untitled, 1987 Aspen ArtWeek

I never expected Aspen to be so beautiful—it’s a low-rise town lying in a verdant valley, though the rainy season lasts six to eight months here. It also happens to be booming with billionaires. This is fortunate for the Aspen Art Museum which holds an annual ArtWeek every August, a week punctuated with an art auction and gala to benefit the museum (ArtCrush); art talks, performances and tours; an art fair (Intersect Aspen); lots of cocktails and some very swanky dinners. The special honoree of ArtCrush this year was LA’s own Gary Simmons, and one of his paintings was part of the live auction, which took place during the August 5 gala. ArtCrush, the museum’s biggest fundraising event, raised over $4.3 million this year from both live and silent auctions.

The museum has been enjoying a major collaboration with Italian designer and artist Gaetano Pesce, whose vinyl rendition of sunrise in the mountains now covers the entrance side of its facade. There’s a gallery of his whimsical sculptural work inside, and a tabletop version of mountain peaks in different colors is for sale.

Meanwhile, Aspen galleries have put on special shows to coincide, and one of the best things, especially if you come from LA’s urban sprawl, is that nearly everything is within walking distance. There is also some symbiotic overlap between museum and galleries: certain ArtCrush artists were also featured at galleries, where the art stays up much longer. Two of my favorite shows were Alison van Pelt at Casterline/Goodman Gallery and preparatory drawings by Christo and Jeanne-Claude at Hexton Gallery.

A Forest for the Trees installation, photo by Aaron Mendez Immersed in Immersives

In my spare time, of which I have surprisingly little, I’ve been catching up with immersive exhibitions popping up all over town—the ones based on works by artists, such as the multimedia exhibitions of van Gogh, Klimt, Banksy and Glenn Kaino. Most of these exhibitions have you walking through very large rooms with 360 degree projections of artwork morphing into other artworks or graphics. The Kaino one is quite different—mostly installation, with sculpture and animatronics, and focused on environmental themes.

Often, there’s a lot of posted text—to give the experience an educational tone, I think. The Klimt immersive had about 20 panels of text before you entered the fun part, and I especially liked the excerpts of letters between Vincent van Gogh and his brother Theo in the van Gogh lobby. The Banksy immersive was most like an exhibition, divided into thematic groupings of his work with intro panels like “Banksy and the World Artistic Culture.”

Some also have a VR component, where you fit a heavy helmet with goggles over your head. The one for Banksy was especially good—a joy ride going through a complex of abandoned warehouses, as if you were on a train. His artwork appeared on the left and right on walls, just as his street art does in real life.

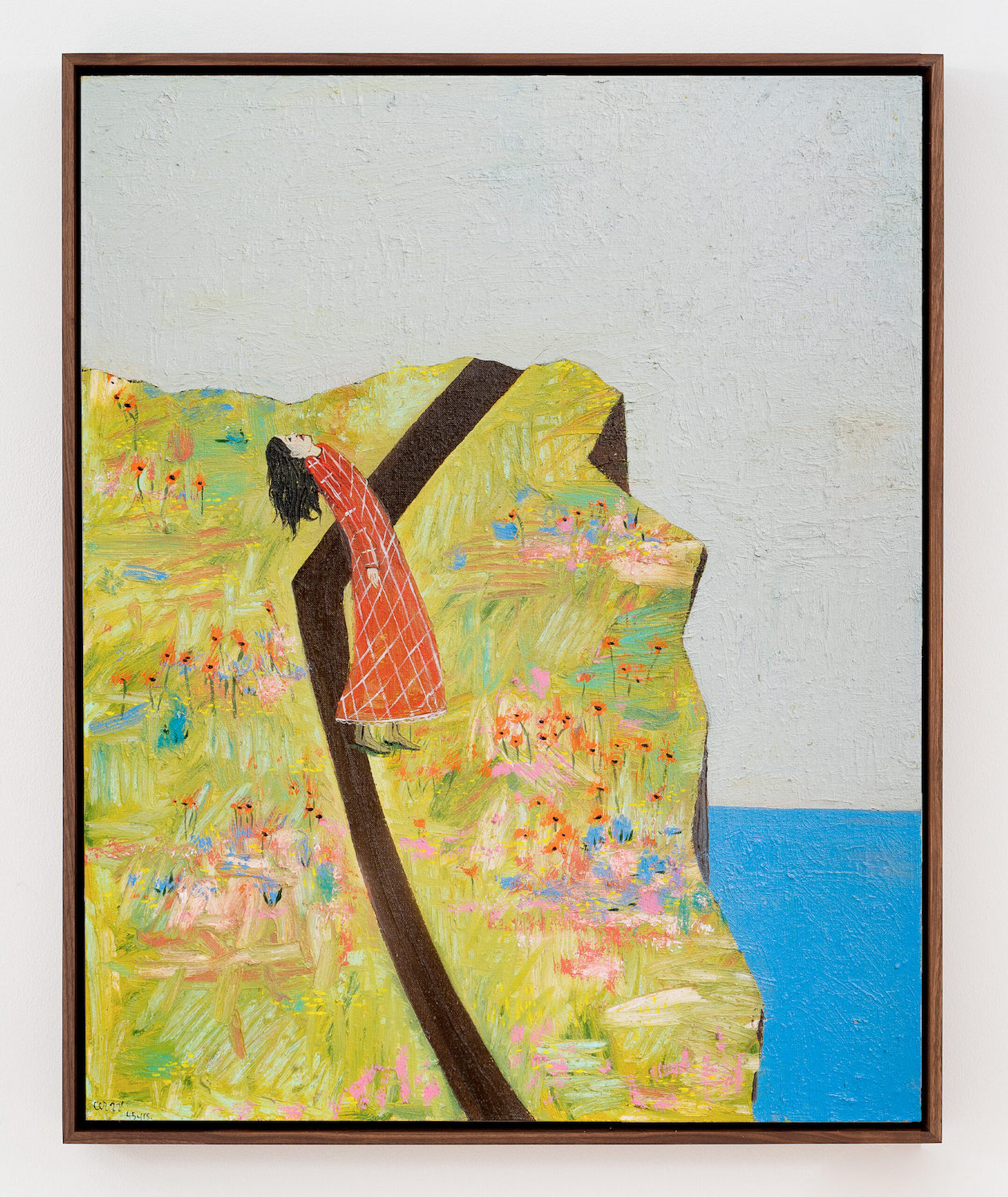

Clare Rojas, The End of the Road at the Edge of the World, 2022 Comings and Goings

In July and early August, San Francisco gallerist Jessica Silverman tested the LA waters with a pop-up gallery on North Robertson featuring paintings by Clare Rojas. Some work delighted with pure geometrical abstraction, while others, like The End of the Road at the Edge of the World, 2022, seemed part of a fairy tale. Silverman is happy to report that the show nearly sold out. Will she be coming back to LA in one form or another? I hope so, as I’ve enjoyed my two visits to her SF gallery. Patricia Sweetow, another Bay-Area dealer, has made her move permanent, settling in the Santa Fe art complex shared with high-end galleries Vielmetter and Wilding Cran.

Sadly, Bridge Projects has closed its Melrose gallery, as of July 30. I saw some excellent work there, but it was never clear to me whether they were a profit or nonprofit, as they also showed some quite quirky and esoteric work. Turns out it was actually a commercial gallery, with some underwriting from a collector couple. The projects will continue though, and first up is a reiteration of a show that opened during the pandemic, “To Bough and to Bend.” Check it out at the Frederick R. Weisman Museum of Art at Pepperdine University, from now through March 26, 2023.

-

COMMENTARY: Stop Being Supportive

“Dictatorship in the arts, democracy in everything else.”

—Dave Godin

It might come as a shock to some young people but there was once a time when not every single person was an artist.

People are always talking about “the role of the artist in the digital age,” as if it’s an entirely different game these days, and, it’s true, things are very different: The art world has become both less and more competitive now that almost everybody thinks of themselves as being a writer and/or an artist owing to the mass delusion of artistic credibility facilitated by the dubious freedoms of the internet.

What a felicitous turn of events it is that you happen to like the work of all of your friends, and that all of your friends like your work in return. One posts one’s poems, paintings (or, worst of all, one’s photographs) online, one’s friends like them, and this means that one is some sort of artist. The more friends one has, the more of an artist one is.

To exist on social media is to exist in a realm of constant unanimous, reciprocal admiration, surrounded by yes-men and women who unreservedly validate one’s aspirations and pretensions. If somebody likes you as a person, or wants you to like them, they like your work. That’s all it takes. As Oscar Wilde observed, “Bad artists always admire each other’s work.”

With the lack of quality control in the digital age there is no escape from essentially talentless people playing at being artists. Most of them are wasting their time, and everybody else’s, by assuming they have anything of value to contribute. And forget about style or originality: that all went out with the manual typewriter.

It is now impossible to stop this torrential influx of vanity art and unchecked mediocrity. The doors have been flung open and it’s a free-for-all of collective narcissism that has spread into the fickle realm of galleries and publishing houses. If one commands enough of a social media presence—if one has enough friends—the powers that be will be much friendlier towards one. I would cite examples of this all-too-pervasive phenomenon but I’m on cordial terms with some of the people whose careers have benefited from it and don’t want to risk upsetting their fragile egos. Time will shake them out. Or will it? Maybe this sorry state of affairs could go on forever. Maybe it could get even worse. There’s no reason to think it won’t. It has been getting worse for years.

How are these punishers, pretenders, poetasters and Renaissance dabblers going to realize they’re getting away with murder if nobody ever tells them? On a personal level, even if it is for their own good, it is difficult to criticize the work of an acquaintance whom one likes as a person, who is talentless but essentially harmless. As is the work itself: harmless. These days it often presents itself as being dangerous, subversive, transgressive, etc., but it is completely harmless: Transgressive is the new harmless. Anyway, nobody takes it very seriously, including the artists themselves: the work usually serves only as an occasional cerebral adjunct to the social life.

Artists that can’t draw or paint, writers that have no command of language, singers who have no voice of their own. That’s the new art world order, and the role of the artist in the digital age should be to take a stand and actively discourage people who (shouldn’t) call themselves artists from producing and disseminating their worthless works. We can all do our part, either by ceasing to produce ourselves, or by discouraging others from doing so. The time has come to Stop being Supportive.

-

ASK BABS

Bad-Ass Art-Collecting GrandmaDear Babs, I follow your column and thought your answer to the question concerning censorship of art in one’s own home for the sake of one’s grandchildren was spot on. I’d like to take this issue a bit further. I own a Larry Clark photo that I proudly display on my walls. It’s the cover of Clark’s Teenage Lust book showing teenagers engaging in sex, with the man’s penis exposed. I now have young grandchildren and I’m wondering if you think this photo might be too much for them?

—A Larry Clark Fan

Dear Larry Clark Fan, Thanks for reading my column (and the compliment). I think your scenario is a bit different because it revolves around a specific work of art, so allow me to elaborate on your description: The untitled photo from 1981 is of a naked couple French kissing in the backseat of a car. The young man’s hand modestly covers the woman’s genitals, and while she does hold his penis, it’s not necessarily erect; her hand covers its shaft, and the camera captures only the tip.

Clark’s other photos in this pioneering body of work are much more explicit, including teens shooting up and full-on fucking. The picture you have is comparatively tasteful and far from pornographic. It’s an image that echoes Egon Schiele’s drawings, Manet’s Olympia, and many classical sculptures. I don’t think it’s going to corrupt your grandchildren. It’s art, and they’ll see it as art. If anything, I bet they’ll ask why the car’s backseat has no seat belts.

I wonder how Clark’s photo interacts with the other art in your house. Is it next to a family portrait? An abstract painting? A mirror? Is it in the living room, bedroom, bathroom, or kitchen? If you move the Clark photo, shouldn’t you consider moving everything else? Maybe it’s time to consider if and how you might rearrange your collection to best shape the conversations you want to have with your grandkids now and in the future. Or don’t change a thing; it’s your house after all, and you get to put whatever art you want in it. If it were me, I’d want to be the badass grandparent with the famous Larry Clark photo, even if it means I have to have some awkward conversations along the way.

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,