Back in the days before television, radio and movies, a popular form of entertainment was the Tableau Vivant. People would pose in costumes alongside elaborate props to reenact historical events, or to mimic paintings and statues. If you have ever encountered the Pageant of the Masters in Laguna Beach, you have witnessed the modern-day version. Tableaux Vivants offered a way for people to be onstage without any special talents or having to learn any lines. Over the years films have often referenced paintings, at times only subtly, where it may or may not be intended for viewers to notice. Andy Guerif’s 2015 film Maesta La Passion du Christ takes this concept to the next level.

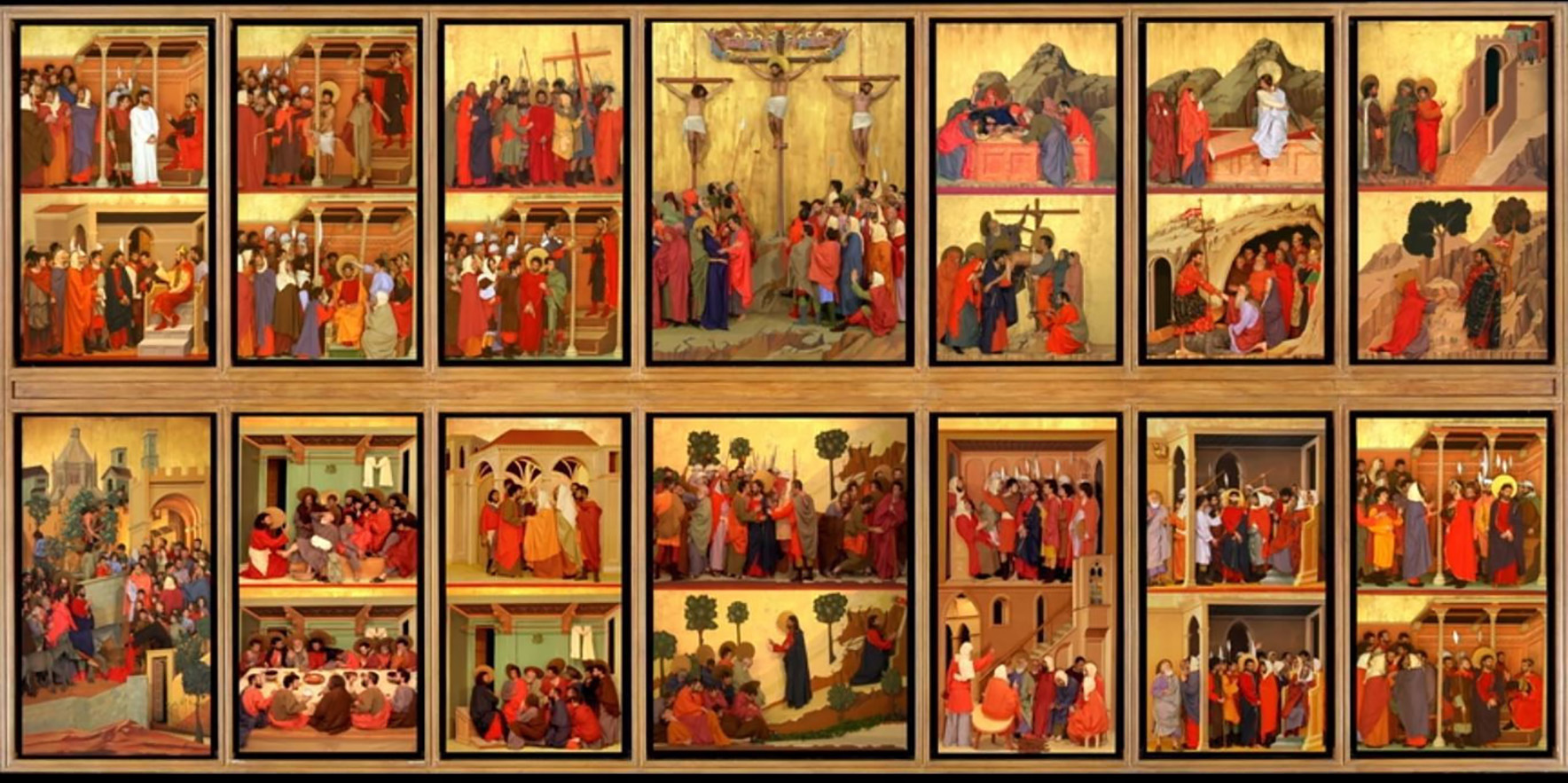

The Maesta by Duccio di Buoninsegna (1308) is a giant 26-panel altarpiece that portrays the passion of Christ from the entrance of Jerusalem to the road to Emmaus. Any single panel of this work could make for a full evening of Tableaux. The filmmaker recreated the background of each panel on stand-alone sets reminiscent of Japanese screens. The sets are stitched together digitally. Sometimes people will move from one set to another, and in other cases they will vanish when they walk out of the frame. The cast is attired simply in vividly colored tights and black socks, simple tunics and carefully draped pieces of fabric. These actually cause them to seem less three-dimensional against the gilded backdrops. The way that the action moves from one panel to the next might bring to mind players on a board game. By way of anchoring the action, two characters spend the movie in the upper two right hand panels building what appears to be a tomb. Characters will fill a panel with action that looks like a scene being naturalistically acted out. When they reach the moment where the figures match those in the painting, they all freeze in place. Then they carry on the rest of the scene that leads to the next panel.

Once all of the frames have filled and emptied, we are treated to a final look, with all of the panels filled with people interacting, and then frozen in unison. This bookends nicely with the opening scene which focuses on the single crucifixion panel. It is fully acted out before the title appears. In addition to its function as a storytelling device, it gives us a closer look at the details that create the illusion that this is a painting come to life. Without seeing this close-up, look at the details that give the illusion of a painting; one might conclude that what we are watching is some interesting CGI. The precision of the choreography that allows the camera to freeze on a still shot without carefully posing each cast member to match the painting makes what you see look deceptively simple and natural. This would work beautifully as a gallery installation. Watch it on the biggest screen that you have access to.