Your cart is currently empty!

Category: features

-

KIND OF BLUE

That’s what black people are, myths. I come to you as a myth,” announces Sun Ra in a scene from Space Is The Place, the marvelously entertaining mixture of blaxploitation, space travel, mysticism and free jazz that screens on one of the many video monitors at the “Blues for Smoke” show. By this, presumably, he means as myths to people of other races, particularly white people—and nowhere is that myth more evident than in attitudes to the blues, which has been such a seductive and potent force in white culture. As Greil Marcus observed, it is “a world that once glimpsed from afar can be felt within oneself,” which succinctly captures its allure as a harsh reality prone to vicarious idealization by susceptible outsiders. Thousands of definitions—often in song—testify to its elusive but pervasive nature: “A lowdown shaking heart disease,” “Nothin’ but a good man feeling bad,” etc. Or as Sam Chatmon memorably remarked, “The blues, that was nothing but a lost calf cryin’ for his mama.”

To judge by its title and surrounding publicity one might assume that this show examines the connection between blues—the most un-self-conscious of mediums—and modern art, the most self-conscious. But the further I ventured into the exhibit the more another Sun Ra title came to mind: “Some Blues but Not the Kind that’s Blue.” The blues as a musical form and its closely linked state of mind—the blue devils that plagued many an 18th-century poet—is mostly conspicuous by its absence in a show that focuses on blues less as myth and more as a broad but vaguely defined ethos that runs like a current through black culture.

Musically, the show, named after a Jaki Byard composition, is steeped in jazz: not only pictorially—as in Roy De Carava’s photographs of John Coltrane or Bob Thompson’s GauguinesqueGarden of Music, featuring Ornette Coleman and other forward-thinking jazz luminaries grooving in a pastoral landscape, but also sonically, in Albert Ayler’s Spirits Rejoice, squalling forth from a video by Stan Douglas into surrounding galleries. At one particularly discordant junction the Ayler audio clashes with three other jazz recordings blaring out of boom boxes set up on the floor in David Hammons’ “Chasing the Blue Train” —an installation in which a blue model train circles a landscape of upended pianos and rock piles—to create a cacophony that must surely wreak havoc on the nerves of gallery attendants. Meanwhile, The Last of the Hill Country Bluesmen, a documentary about contemporary rural blues, is hidden away in the Reading Room, the most obscure part of museum. To the untrained ear the rough hollers of Son House and the elegance of Ellington may not seem to have much in common, but apparently they’re related. The blues is the source of it all, and as Claude Levi-Strauss said, “Man never creates anything truly great except at the beginning; in whatever field it may be, only the first initiative is truly valid.”

So maybe the show isn’t strictly blues-related—as I have come to understand it from a romantic, pedantic, pampered, white European perspective—but all the same, a catalog discography in which works by R.E.M. and the Walker Brothers are listed, but nothing by Blind Lemon Jefferson or T-Bone Walker, is confounding. When the forefathers of a form are ignored in favor of the most tangentially connected it raises the question of just how far parameters are being stretched in the interest of allowing the curator to take off on a few solo flights of his own, as is so often the case nowadays in surveys and critical studies that delight in muddying the waters by connecting dots between unrelated subjects in order to draw attention to curatorial or authorial erudition. And if you’re trying to draw a bead on what this particular show’s about you won’t get much help from the catalog essay. “A blues sensibility requires the critic to think beyond traditional categories of representation,” states MOCA Curator Bennett Simpson. “I tend to mean a kind of tradition,” he continues, “something akin to the ‘Great Black Music’ idea that began to circulate at the end of the 1960s.” After several thousand words and much confusing talk of ideologies, idioms, aesthetics and sensibilities, he finally arrives at something resembling a statement: it is what art historian Richard J. Powell called “basic, 20th-century Afro-American culture.” Which would explain the heterogeneous nature of the exhibit.

All rock music, of course, is blues-based, and that would include Liz Larner’s sculptural homage to Lux Interior, a punk/rockabilly singer, and performance footage of hardcore/straight-edge band Minor Threat. You might as well throw it all in, from Jean-Michel Basquiat’s wildly inspiredUndiscovered Genius of the Mississippi Delta (in which a goateed portrait is referred to as Robert “Johnson-esque” in the accompanying wall-notes. This cat looks a lot more like Eric Dolphy. Come to think of it, I can’t think of a single prewar blues musician who sported a goatee or beard. But why quibble? Because it’s fun… for the quibbler… it contributes to and expands the dialogue, right?) to Charles Gaines’ algorithmic grid drawings—known as the “Regression Series” —which have all the flavor of a train timetable without arrivals or destinations and make Agnes Martin look like an expressionist by comparison. But maybe it has something to do with a train, which has something to do with the underground railroad, which…

After a while it becomes wise to disregard all the blues, smoke and mirrors and just enjoy the show, which isn’t hard to do, as in many ways it is stronger for the liberties taken. Another piece that evokes travel, Zoe Leonard’s 1961, a row of blue suitcases stretching across the floor, has a wistful power. It’s hard to say what Rodney McMillian’s installation, “From Asterisks in Dockery” —an almost life-size red vinyl church with red vinyl benches, altar and lectern and a bare bulb hanging from a red vinyl ceiling—has to do with the Dockery Plantation where Charley Patton and other early Mississippi blues singers resided, beyond its convenient reference point, but it’s a unique creation.

Racial unrest was seldom directly addressed in blues lyrics, a reticence which in itself constituted an indirect form of defiance. Here it can be found, among other places, in Melvin Edwards’ metal assemblage sculptures, known as “lynch fragments,” while the silhouetted rape and murder scenes in Kara Walker’s Fall From Grace are beguiling and provocative in their tension between brutality of act and delicacy of execution. This antebellum-era shadow puppet show is the only work on display whose subject matter predates the 1920s era of blues recordings, which, say what you will about its later permutations—musical, social or anti-social— is the bedrock and quintessence of any subsequent blues sensibility. It was in those pioneering recordings that the restlessness and alienation that went on to suffuse every avenue of 20th-century popular culture—so abundantly apparent in this show—was first given commercial expression.

“Blues for Smoke” travels to the Whitney museum in New York and runs through April 28, 2013, whitney.org

-

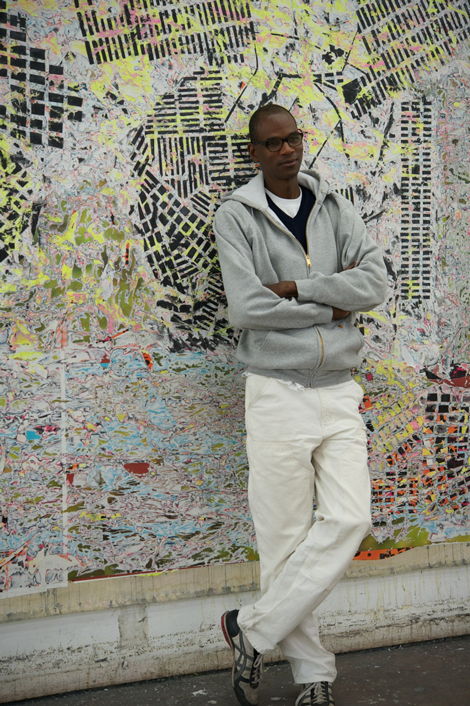

Mark Bradford

In the Leimert Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, the anonymous unmarked storefront of Mark Bradford’s studio betrays nothing to passersby, but the large white security gate which rolls back to reveal a parking lot at the north east end of the property is an unusual flourish for the area. Inside, the multi-building space is organized and impeccably neat. Cocoon-like, it feels insulated from the traffic and continuous motion outside.

Bradford however, is inspired by the pace and the multiplicity of voices that compete for the public’s attention on the streets outside. The artist’s older works incorporate signs and posters scavenged from the surrounding neighborhoods, with the signage collaged onto his canvases. Although he says he almost exclusively purchases his paper now, he continues to use text from the “merchant posters” he encounters around the city, which advertise the services of lawyers, social services agencies and various other business ventures, reflecting the socio-economic realities of the city’s populace. His large scale canvases—which he very strategically calls paintings even though they are almost exclusively built up with layers of paper—are intensely process-oriented in a cycle of creation and destruction. He often outlines these texts on raw canvas using string or paint, then obfuscates by adding layers of paper, or obliterates by sanding, leaving only a trace when the painting is complete.

On a clear November afternoon, Bradford welcomes me into his office for the first of two studio visits. Over the course of our conversation, he meets my interest in discussing his youth living in Santa Monica and working in his mother’s hair salon in Leimert Park with a certain amount of reluctance. While he does offer some detail, most of his life story is drawn in broad strokes, and it is not until our second meeting that I come to understand, in its entirety, his practice of very clearly delimiting his biographical narrative.

Mark Bradford at his Los Angeles studio in front of a work in progress. Photo by Tyler Hubby. Bradford credits his early experience with preparing him to navigate diverse environments. “I’ve been naturally hybrid,” he says, explaining that he has never belonged all to one community. Bradford’s mother was an orphan. “She didn’t come from a lineage of people,” he tells me. Bradford considers this early rupture one reason for his fluidity. Referring to the lack of an extended family, he says, “It was just my mother, and we”—Bradford, his mother, and his two sisters—“lived in a boarding house, which was still with people who were not living in a traditional family unit. So, I grew up in that, and I went from that to Santa Monica.”

Bradford attended CalArts, earning his BFA in 1995 and his MFA in 1997. “I thought about art-making—professional art-making— like everyone else,” he tells me, when I ask how his early development affected him as an artist. “I went to school, like everyone else, and I learned the same texts, and I learned the same structure, same rules of engagement. So I just assumed that you leave your past behind, and you begin to build a practice. So, I don’t think I was any different than anybody else, really. I didn’t bring much of my personal subjectivity into it.”

Bradford credits CalArts with opening him up. He quickly found his way into the cultural studies department and started reading writers like Homi Bhabha, Bell Hooks, and Cornell West, as well as Walter Benjamin, Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault. He became fascinated by the dynamism of emerging power structures, and observant of the way the world was changing. “I immediately understood that there was art theory, and that there was social anthropology. They were different departments, different people, and I also became very clear that it was a hierarchical relationship.”

At the same time, Bradford began encountering the hegemonic gaze. He found that his body was “constantly propelled forward,” he says; there was an expectation from others that his body was “supposed to be in the work.” Never before had he found his physicality “so forcefully brought to the table.” Even now, people fixate on his stature, commenting about his height, sometimes telling him, ‘if I were your size, I would…’ fill in the blank, most frequent being a reference to basketball. He quips, only half joking, “that should be the name of a piece, Well, If I were you.” A pause, then, “I’m six-foot-eight. My god,” he says, not letting writers off the hook either, “there’s very few articles that will not describe how I am.”

“So when I started to make abstract paintings, I’m sure that it was for me at the time—it was not a critique, quite yet—it was more trying to find an ideological framework that I felt would give me some space to figure it out.” Bradford was inspired by Malevich and the idea of not making images “for the people,” referring to the Russian painter’s refusal to make the Social Realist paintings encouraged by the Soviet regime. But his foray into using paint on canvas was short lived, since it seemed to him, too weighted with the history of painting, and “too heavy on the CV.”

“So I really just started working, and I just kind of came on to paper. I liked the idea that it engaged the cultural anthropology readings that I had read. It simply engaged immediately, that side, for me.”

Bradford’s interest in power structures, emergent when he was at CalArts, has continued to inform his painting, and how he conceptualizes his work. He has always been fascinated by the purity that is attributed to paint and that collage is considered lower than painting in the spectrum of media. “I was building a political framework in my head of how I wanted to engage, and what materials could push that. That is why I demand that they’re called paintings,” he says about his large scale paper-on-canvas works. “That is why people get unfurled when I call them paintings. That is why the purists stand up and say, ‘There is no paint.’” Bradford also notes the lack of African-American men and the lack of women throughout the history of painting. Finally, he points to the question of space. “Certain white men are allowed to be size-queens; they have big paintings, they can take up big spaces. It was about who was allowed to take up space, and who was allowed to not take up space. So I think for me, all this framework came out of being at CalArts and observing ideological frameworks and my relationship to them.”

While he was at CalArts, Bradford encountered the conceptual artist and professor, Charles Gaines. He took note, from a distance, thinking of Gaines as a mentor. Bradford adds that when he was growing up, while he knew many black women from the hair salon and the boarding house, he didn’t interact with many black men. But he knew from early on that he did not fit into a traditional role. What Bradford calls the narrowness of socially accepted roles for black men was not something he was comfortable with or wanted. The most prominent black male archetypes in American culture, he says, are the athlete, the rapper, the gangster, and the good pastor. Gaines was a compelling figure, “because he was a black man, who was non-traditional, and I had never been up close with that.”

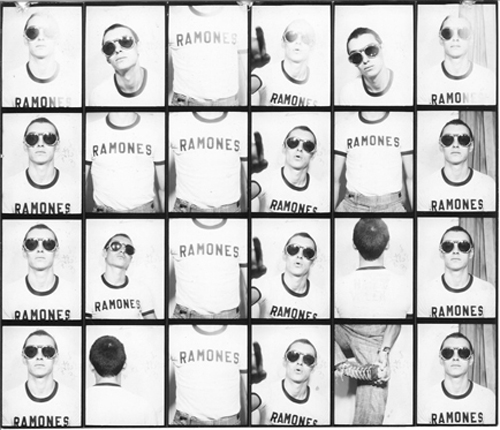

Although the two artists’ modes of production are dissimilar, there is a confluence between Bradford’s thinking and Gaines’ 2008 video, Black Ghost Blues Redux, in which, Gaines explores identity constructs, examining how black men often are either culturally invisible or romanticized. In the catalog that accompanied Bradford’s survey at the Wexner Center for the Arts in 2010, Bradford is quoted as saying he has to continually “fight erasure and rigid identity constructs at the same time.” He explains, at length as we talk, the risk of being pigeonholed as an artist who tells the “real story based on race,” whenever any discourse of race or community is remotely attached to the work.

Rigid constructs can also affect the way communities see themselves or individuals within the community as much as they can affect how those outside see them. Niagara, a video Bradford made in 2006, follows a man in Bradford’s neighborhood walking down the street with an exaggerated gait. We discuss styles of walking and what they communicate. “It’s huge,” Bradford clarifies, and says it’s called “swag; he [the pedestrian] had such an identifiable brand that it made me uncomfortable to look at him. I was scared for him. He felt vulnerable and heroic at the same time. I knew that it could turn bad.”

“I understood the way in which this part of town has been historicized, politicized, romanticized,” Bradford tells me. “I love this one detail of this man that was just really breaking everything, crushing the idea of what it meant to be in South Central, with this ownership of this kind of promenade.” He continues, “You would never think of that imagery when you think of South Central. So I love to point to details that point to other conversations.”

Mark Bradford, Bell Tower maquette in his studio, 2012, Courtesy White Cube, London, UK Our conversation turns to Bradford’s new work, a sculpture that will be installed in the coming months for the opening of the Tom Bradley International Terminal at LAX. Bell Tower, which is modeled after a JumboTron screen, will be suspended over the TSA screening area of the terminal. He wanted to make something that referenced the way technology manages people, but also something atavistic. Historically the bell tower is simultaneously a site of surveillance and warning, as well as civic and cultural celebration. The maquette for the piece, which hangs from the ceiling of his studio, looks huge, yet it is only one-third scale. The interior is a spiral that creates the visual effect of a vortex.

On our second visit, Bradford suggests we drive to a new studio he has rented specifically to fabricate the panels for Bell Tower. It is in a small business park about a mile away. Inside the studio approximately six feet beyond the door is a temporary 2×6 frame wall. The opposite side which faces the interior of the studio is covered in weathered gray plywood and is angled out as if cantilevered, overhanging the floor. It looks like a giant JumboTron. Around the perimeter, stacks of plywood lean against the walls.

“We buy these boards from a guy who puts them up,” Bradford says. “They come just like this,” and he points to a weathered board with a coat of battleship-gray primer and advertising remnants. “We crow-bar off all the work.”

Two boards have matching posters of the rock band KISS, which Bradford says he’ll keep for his archive. “…this is so good,” he says under his breath, “they’re the best painting.” We line them up to view the posters in stereo.

“The paper’s really, really thick, though,” Bradford maintains, and he shows me a stack of salvaged advertisements in the corner.

Bradford discusses Bell Tower in the context of how societies use signals to organize, to move people, or to regulate behavior. “It’s the same thing at sporting events. I was at a Lakers game not too long ago,” he continues, describing how the JumboTron cued the crowd’s behavior as he watched a sea of people switch their attention from the floor to the JumboTron and back. “Watch the game, and now watch the kissing-cam. Whatever the technology is telling us to do, we do it.” Bradford draws the same comparison for airport arrival and departure screens. “You look up and it says gate number 37, and you just go to gate number 37. We’re so comfortable with being controlled,” Bradford concludes.

“The singular body is vulnerable in these spaces,” Bradford adds, “The singular body that looks up at these,” – the JumboTrons, airport displays, and TSA screening areas – “gets lost, and doesn’t know where to go.” He adds, “That’s why I wanted to use this,” and he raps his knuckle against a sheet of ply. “This has a very different relationship. It puts it down to street level,” he says, referring to the plywood’s function as construction barricades. “It all has to do with the ways in which our physicality can be so controlled.”

I ask Bradford if this is one of his reasons for resisting the pressure to make his body a subject of performance when he was at CalArts. “Absolutely! I just would not do it,” he tells me emphatically. We discuss the question of biography and his reluctance to speak about it. Bradford says that biographical narrative is expected from him, whereas, white male artists are not asked about their relationship to their community or the cultural mainstream. “That is not the case,” he says, “with the black body.” I suggest that biography can be compelling and refer to my own interest in it. He responds, “Hell, to be honest with you, its probably more damn interesting coming from you, because it’s like, you guys are the ones who don’t have to share it, so it’s more interesting coming from your side.” He laughs, adding, “Hell, we get it all the time. ‘Latina, tell it to me. Black man, tell it to me. Asian, tell it to me.’ And it’s more interesting when they don’t, and you do.”

-

A Women’s Place

Slender, dark-haired Lisa Aslanian speaks softly but with conviction as she shows visitors around her sparsely furnished 1,000-square-foot space, The George Gallery. The venue derives its name from George Sand, a pseudonym for the intrepid 19th-century writer Aurora Dupin.

On North Coast Highway in Laguna Beach (a city halfway between Los Angeles and San Diego), where ocean breezes waft in the door and commercial art is prevalent in nearby galleries, Aslanian exhibits women artists only—each with a provocative perspective. In this intimate gallery, providing a framework for these artworks, she explains, “The way we experience art is influenced by where it is housed, and that housing is like a place of worship.” In this “housing,” she challenges her viewers’ visual literacy with lyrical, figurative, sculptural and abstract art that examines feminist and gender issues, with some works presenting aggressive sexuality and/or parodies of domesticity.

The former art professor at The New School for Social Research in New York opened The George Gallery in January 2012. When asked about her artists, she points to the images on the walls and eagerly pulls pieces out of storage. “Her canvases are so alive, layered, complex, and full of life, colors and shapes,” she says of a Mary Jones’ abstract painting. She also represents Jill Levine’s pre-Columbian sculptural dolls which allude to a pan-cultural symbolism; Theresa Hackett’s abstract paintings, combining ordered chaos with female shapes; photos by Carla Gannis, whose contemporary “Jezebels” are saturated with intense reds reminiscent of mid-century “noir” films; and Sandra Bermudez, who shoots close-ups of deeply colored lips with pop aspects.

Aslanian seemed destined to open a gallery dedicated to gender issues, as these concerns have haunted her since childhood. Interviewed on a warm autumn afternoon, she is forthcoming, thoughtful, intelligent, telling me how she created her gallery based on her personal passions and scholarly engagement.

As a suburban New Jersey teen, she discovered the French writer Albert Camus, remarking, “His claim that the only reason to live is that there is nothing quite like this day, this moment, was one of the most beautiful ideas I ever read.” She also spent time frequenting art museums in Manhattan. Later, in college, she pursued her passion for art, culture, philosophy and French literature.

Lisa Aslanian at her gallery After extensive travel, followed by completion of an art history doctorate at The New School, she began teaching in downtown Manhattan, within walking distance of galleries and museums where she and her students were able to experience that vibrant art world directly.

Aslanian later married and had twins, while continuing to teach. But her life changed dramatically when she and her family moved to Orange County in 2008. “I expected to teach here but there were no jobs.” Relegated to staying home, she taught herself Spanish and spent hours reflecting on her life. “As a stay-at-home mom, I had a personal conflict between ambition and nurturing.” While caring for her children, her ambitious side compelled her to re-examine her lifelong interest in contemporary art.

Soon after, while going through a divorce, she sought sanctuary as a gallery assistant at Salt Fine Art in Laguna Beach. “The art there is loaded with sociopolitical commentary and observations about violence, sexuality and submission. While working there, I finally determined to open my own gallery.”

Among the dozens of female artists who inspire her—whose work she finds penetrating and revelatory—are Marina Abramovic, Marlene Dumas, Frida Kahlo and Dorothea Tanning. She explains that these women’s liminal art may bring us to the edge or open us to another plane of existence, adding that their confrontation of gender issues can threaten us on a fundamental level.

While feminist art has been around for decades, few galleries address these issues exclusively. The George Gallery is in fact an anomaly in conservative Orange County. “While interested people have come here out of the woodwork, I am not sure there are enough local buyers to sustain us,” she says. Yet the gallery’s innovative perspective, exemplified by its recent “Pop Noir” exhibition that explored the intersection of popular culture with desire and perversion, created a buzz way beyond OC’s borders.

Aslanian plans to keep her current venue while also expanding to Los Angeles, where the art, she says, “will be gutsier and more conceptual, with fewer traditional media.” And perhaps where it will live up to the fearlessness of its namesake, George Sand.

Info@Thegeorgegallery.com

-

NEIGHBORHOOD WATCH

One of the largest survey shows of contemporary Canadian art ever produced, “Oh Canada,” is the culmination of five-year’s research and 400 studio visits by North Adams MASS MoCA curator Denise Markonish. It joins a history of international survey exhibitions of Canadian art as well as biennials in Montréal, Alberta, Quebec City and by the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa from 1926 to 1989. The project’s scale—120 works and 10 commissions, by 62 Canadian artists—is a testament to Markonish’s genuine curiosity about Canada and the impressive scope of contemporary art being produced there.

Realizing that she knew more about artists from China than artists from her northern neighbor, Markonish set out to counter what she calls an “extreme exoticism” in the art world by looking for work closer to home. For better or for worse, she chose not to include many of Canada’s best-known visual art exports: Vancouver photoconceptualists like Jeff Wall, Roy Arden and Rodney Graham, or others like David Altmejd, and Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, who now mainly live and work abroad.

“Oh Canada” is an idiosyncratic snapshot of current art that highlights several surprising works by Canadian artists. It has no overall theme, but there are a number of inter-related ideas—conceptualism, cultural hybridity, colonialism, material and craft practices, surreal humor and popular culture—introduced in the 450-page catalog, which includes Markonish’s epic essay, “Oh, Canada: Or, How I Learned to Love 3.8 Million Square Miles of Art North of the 49th Parallel,” reflections by creative writers, critical regional overviews by Canadian curators, artist-to-artist interviews and a historical timeline. Notable is the impressive legacy of Canadian conceptual art, which had its heyday at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (NSCAD) in Halifax in the ’70s under the leadership of conceptual painter Garry Neill Kennedy, who produced new work for the exhibition. Process painter Eric Cameron, known for his thick paintings, would arrive there from the U.K. and later migrate west to teach in Calgary, as would performance/installation artist Rita McKeough, a Halifax native who now teaches at the Alberta College of Art + Design. Octogenarian Ontario filmmaker and jazz musician, Michael Snow’s 62-minute fixed frame video Solar Breath (Northern Caryatids) (2002) evocatively recallsWavelength (1967), a conceptual classic about place, space and time. Lines of association are drawn between these artists and other generations of NSCAD alumni: Micah Lexier, Kelly Mark, Graeme Patterson and Michael Fernandes, as well as diverse conceptual practices in other parts of the country.

Marcel Dzama, A Game of Chess, 2011, black and white video projection with sound, Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York Much of the work engages material and craft-based practices that re-materialize the art object through process, labor and hand skill, hallmarks of late conceptualism. Luanne Martineau’s felt-sculpture Form Fantasy (2009) straddles high modernism and craft, mashing-up references to Robert Morris and Barnett Newman with feminism and popular culture. Gisele Amantea’s site-specific commission Democracy (2012) cloaks a long entrance foyer with an enlarged black velvet flocked design by the American modernist architect Louis Sullivan, who saw ornamentation an expression of democratic principle. Ornamentation is seen as an expression of conquest and violence in David R. Harper’s Finding Yourself in Someone Else’s Utopia(2012), and it becomes indicative of class and gender in Clint Neufeld’s cast porcelain truck engines displayed on Victorian settees. A younger generation of painters, Etienne Zack, DaveandJenn and Chris Millar construct baroque narrative bricolages steeped in popular culture, the history of art and the materiality of paint; they make paint do things it shouldn’t do!

“Oh Canada” has a playful, wry, ironic tone that artist Pan Wendt says is typical of “Canada’s messy pranksterism.” Indeed the Cedar Tavern Singers have made an artistic practice out of it, and their newly recorded song “Oh MASS MoCA” sings funny anecdotes about Canadians in the Berkshires. Pointedly, John Will’s title wall implicates all of the artists by name, then facetiously cancels them out with a graffitied “NOTHING.” Dark humor persists in Shary Boyle’s fantastical drawings and Spider-Woman installation, Patrick Bernatchez’s surreal film Chrysalides Empereur (2008—11) and a Dada-inspired video by Marcel Dzama. Sentimentality becomes post-ironic in Daniel Barrow’s exquisitely complex projected drawing installation “The Thief of Mirrors” (2011) and in Amalie Atkins’ “Three Minute Miracle: Tracking the Wolf” (2008), a sugary sweet performance and film installation about reciprocity.

The idea of Canada is constantly being re-imagined here. The trickster is alive in Kent Monkman’s double diorama Two Kindred Spirits (2012). It tells an amorous tale based on fictitious duos, Tonto and the Lone Ranger and Germany’s Winnetou and Old Shatterhand, an imagined reversal of colonial power, the legacy of which continues to shape Canadian identity and inflict devastating effects on aboriginal peoples. With reference to the oil industry, Rebecca Belmore and Terrance Houle address how political-ecological exploitation affects us all. Inspired by the Radical Faeries, a gay hippie subculture, Noam Gonick and Luis Jacob’s utopian geodesic dome video installation “Wildflowers of Manitoba” (2008) also imagines an alternative history. More menacingly, Charles Stankevich’s mesmerizing video installation “LOVELAND” (2011) tracks a purple cloud from military smoke grenades across the Arctic Ocean, a sublime homage to Jules Olitski’s Color Field painting Instant Loveland (1968) that also serves as an ominous reminder of current tensions in the far North. The idea of the North is less abstract in Annie Pootoogook’s pencil crayon drawings of the sometimes heart wrenching social conditions in Cape Dorset, and Joseph Tisiga’s watercolors of indigenous life in the Yukon today.

The struggle to maintain an identity while becoming something else is a very Canadian story. In her essay, Markonish notes differences between Canadian and U.S. immigration policies; differences that result in a complex Canadian identity where there is no singular culture but newly formed hyphenated identities. One could argue that since the Canada Council for the Arts (a main funder of the show) was founded in 1957, and artist-run culture began the parallel gallery system in the ’70s, Canadian cultural policy has also chosen to foster diversity within Canadian art. Markonish cites the fierce autonomy of Les Automatistes, mid-century Québec modernists who railed against the provincialism of the Catholic Church; and Greg Curnoe’s radical regionalism in London, Ontario, which struggled to maintain a distinct Canadian cultural identity against the overwhelming influx of cultural exports from the U.S. Curnoe also co-founded Canadian Artists’ Representation (CARFAC) in 1968, which advocates for the improved financial and professional status of artists to facilitate maintaining their artistic practices. So, in amongst the art there lingers a political question too about the differences between the Canadian and American cultural (and other political) systems, and how they affect artistic production in each country. Markonish’s “Oh Canada” seems to yearn, not without envy, for what can be learned from one’s neighbor.

“Oh Canada: Contemporary Art from North North America,” MASS MoCA, North Adams, Massachusetts, through April 1, 2013, for more info: massmoca.org

-

Tomer Aluf

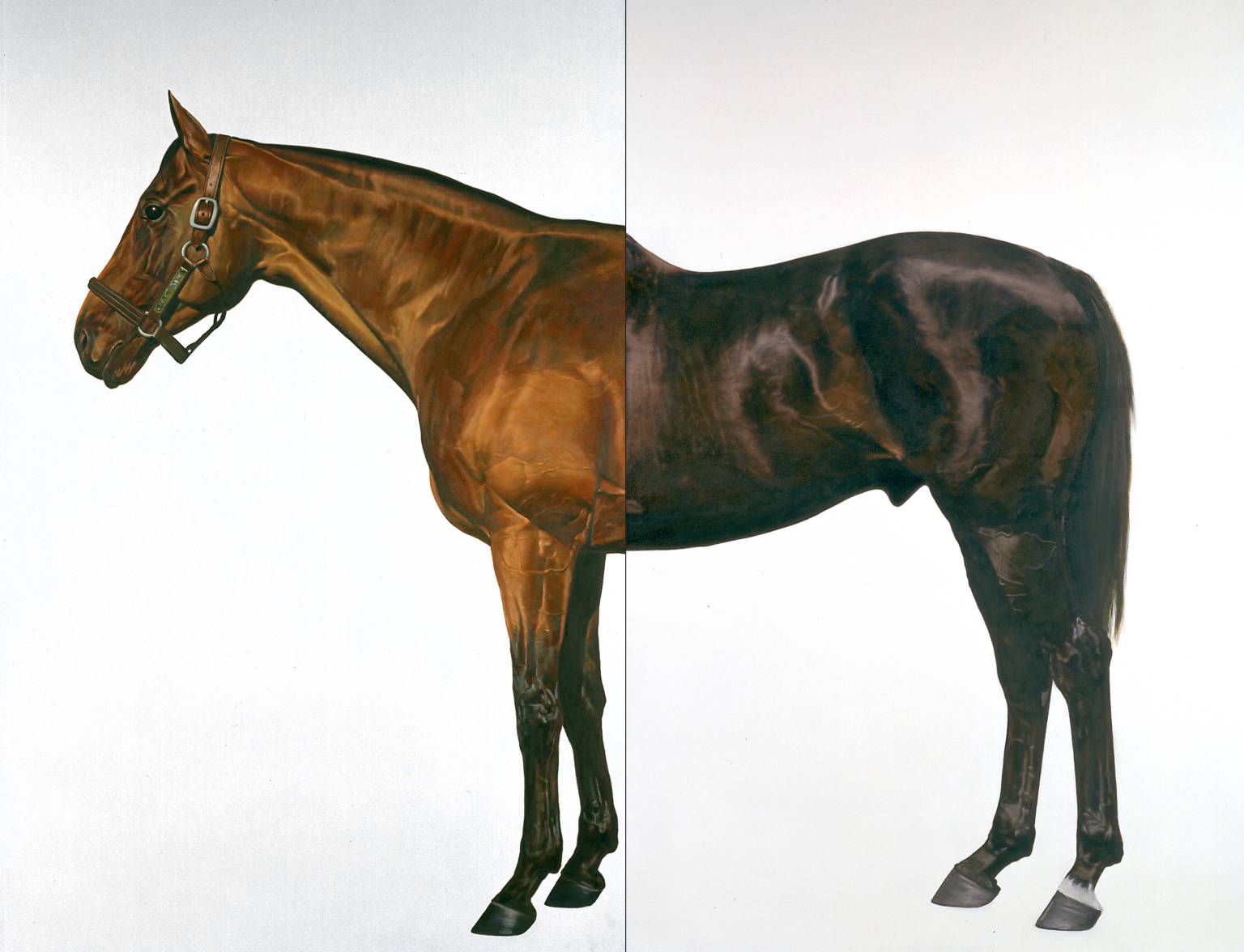

FOR AN ARTIST, FINDING THE ENTRY POINT to a canvas can be the most confounding part of the creative process. Tomer Aluf, a 35-year-old Israeli who has lived in New York City for the past eight years, uses fictional narratives in which he is the protagonist as his doorway. Like an armchair Gauguin, his imaginary expeditions become fodder for his paintings.

“There’s something romantic about being alone in a studio, but in the end, you’re just alone. And you have to find ways to amuse yourself. It’s almost like masturbating, you search for a moment and you try to have fun with it,” says Aluf. Once inside the narrative and the canvas, he’s free to run with it, rebel against it, comment upon it, or whatever he sees fit. “The narrative becomes a structure, a form,” he adds.

The resulting work is semi-abstract, semi-figurative, with portions of the canvas worked out in a very painterly way, and other portions intentionally left unexplored and primitive. The juxtaposition is an expression of Aluf’s struggle with the legacy of great-artists-gone-by, and his questioning of what exactly qualifies a painting as a masterpiece. The raw parts of his canvas are about “not believing you can make a masterpiece because a masterpiece needs to be fully developed,” he says.

Continuing the theme of carving out a place for himself amongst the masters, a recent series is based on the fanciful premise of Aluf touring Morocco with Matisse. “I’m taking a trip with a successful artist who is dead,” says Aluf, a lanky fellow with an easy-going, curious demeanor. “The idea started when I went to the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. I had been painting palm trees on fire, with the pyromaniac masturbating.” But Aluf wasn’t satisfied with the look of his palm trees. “Then, I saw this painting by Matisse of palm trees, and he really knew how to paint a palm tree!” That inspired Aluf to weave a scenario that explores the idea of what it means to be a successful painter, and the idea of learning from a master. “There is something ironic there, too,” he adds.

What Aluf terms as irony comes across more like a sense of playfulness, whether it’s a girl with a strap-on staring at the viewer, or an oddly placed chicken in the midst of what seem to be body parts (executed in a style that’s equal parts Francis Bacon and Philip Guston). His paintings suggest someone who is serious about painting but at the same time does not take himself too seriously.

Aluf spends three to five days a week in the studio, pushing paint for eight to ten hours a stint. “I usually go in [the studio] around 10 a.m., and then it takes two hours to start doing something.” He also teaches art at Rutgers University and runs Soloway, a gallery in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, with three partners. Instead of viewing these endeavors as nuisances that take him away from his studio, he sees all of it as part of establishing a life in the arts.

“You make a painting and it signifies who you are,” he says. “I thought of the gallery as another representation of me. It’s another experience I can have that will add to my life as an artist. When you paint, it’s for you. When you have a gallery, it’s about other people. Even if you don’t love the work, you can still give them a chance. It’s also a great way to meet people.”

Earlier this year, Aluf took off for a real-life adventure: two months in Varanasi, the oldest city in India and by many accounts, the most intense, both in terms of poverty and spirituality. Whether or not the experience will supplant the fictional narratives in his work is unclear. He only recently returned, and is still digesting. “I want to see how it comes out in my work before framing it into words,” he says, adding, “India is crazy, like tripping on acid!”

-

London Calling

Phyllida Barlow, “Rift,” a site specific installation in three parts, 2012: Untitled: hoardings, 2012, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth, London, photo by Maksim Belousov, Mykhailo Chornyy.

DO WE NEED ANOTHER BIENNALE? CERTAINLY UKRAINE SEEMS to think so, with Kiev staking its claim on the international art scene.

From Liverpool to Venice, from Istanbul to São Paulo the world is awash with contemporary art. Is there really enough good work to go round, or, like nature, does art abhor a vacuum, growing to fill the ever increasing number of biennale-shaped holes? An attractive and sophisticated city, Kiev very much wants to be part of the international scene. “If we wait for the good times, we never start,” claims the immaculately coiffed Nataliia Zabolotna, director of Kiev’s Mystetskyi Arsenal, the 18th-century arms store which will become one of Europe’s largest art centers when completed in 2014. The Kiev Biennale’s English artistic director, David Elliott, said earlier this year that “Most exhibitions today are Eurocentric in their assumptions.” While not rejecting this, the Biennale tried to present another picture, one that also took into account the political and aesthetic developments that have shaped so much art of the present. “The international art community’s perception of Ukraine as some kind of a post-Soviet hinterland has changed,” said Elliott. That’s as may be, but E.U. leaders, led by the German chancellor Angela Merkel, threatened to boycott the Euro 2012 football championships held during the Biennale and co-hosted with Poland, in protest at the treatment of Kiev’s former prime minister Yulia Tymoshenko, who was reputedly beaten up after her arrest in October. No doubt there was a touch of British irony in Elliott’s choice of theme taken from Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities: “The best of times, the worst of times: Rebirth and Apocalypse in Contemporary Art.”

On my quick 24-hour visit, the city was busy sprucing itself up for the football. Grass was being laid and flowers planted. The organizers obviously hoped that these dual sporting and cultural events would raise the profile of the country—though it didn’t bode well that during our first tour to the National Art Museum of Ukraine, we found the installation Pipeline “Druzha,” a golden-foil spiral wrapped around the classical pillars of the building’s façade by the artist Olga Milentyi, being removed by the authorities. As one young translator muttered, “We have some problems here with democracy.”

Since the opening of the George Soros-funded Center for Contemporary Art (SCCA) in Kiev, which had its funding withdrawn after the Orange Revolution, it’s Ukranian steel magnate and former politician Victor Pinchuk— who is married to the daughter of the former president of Ukraine and whose estimated fortune exceeds $3 billion—who has become the backbone of contemporary art in Kiev, reminding anyone who was ever in any doubt that art and money often share the same bed. The Pinchuk Art Centre, the first private museum in the former Soviet Union, with its ubiquitous glass, concrete and steel, is every bit the stylish modern gallery. During the Biennale, it is showing work by Olafur Eliasson, Andreas Gursky, Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst, though more interesting for a western viewer overfamiliar with these artists were the intense figurative paintings by the winner of the PinchukArtCentre Prize, Artem Volokytin.

But back to the Biennale. The opening was chaotic, the speeches long, the work not all installed, and we were severely delayed getting in. Explaining the lack of organization, Elliott said, “There are things that you can’t plan for, like having to install for 36 hours with minimal electricity and no light.” Inside paintings were languishing in their bubble-wrap, and wall markers were non-existent or left lying around haphazardly, while technicians drilled holes in the walls, ran out electric cables, and tinkered with the videos.

Despite the distractions, there was much that impressed. A new series of photographs, by Ukrainian Boris Mikhailov, of rusting factory plants that still scar vast swathes of the Ukraine landscape spoke of the collapse of the Soviet dream, while nearby Louise Bourgeois’ “cells” made reference to the repressed feelings of fear and pain underlining Elliott’s belief that “you have to understand the past to understand the present.” British artist Phyllida Barlow had specially created “Rift,” an impressive three-part site-specific installation of wooden scaffolding that stands like some dystopian cityscape responding to the massive columns and vaults of the imposing Arsenal building. Other new pieces included Yayoi Kusama’s site-specific walkthrough tunnel—studded with pink nodules, decorated with black polka dots, and titled Footprints of Eternity—and a vast projection of a letter written in 1939 by Mahatma Gandhi to Adolf Hitler, in which he urged the Führer to avoid war “for the sake of humanity.”

There were works from China (Liu Jianhua and the MadeIn Company), Korea (Choi Jeong-Hwa) and Turkey (Canan Tolon), as well as 20 artists total from Ukraine, including Vasily Tsgolov, Nikita Kadan, Hamlet Zinkovsky and the U.S.-based couple Ilya & Emilia Kabakov, whose trenchant pieceMonument to a Lost Civilisation (1999) reflects the false utopian dreams of those living under communism. The American painter Fred Tomaselli created two large new apocalyptic works, while British artist, Yinka Shonibare contributed paintings that continue his exploration of colonialism and post-colonialism. First shown at the 53rd Venice Biennale, Miwa Yanagi’s macabre 4-meter-high photographs of “goddesses” stood in a windswept landscape. The conjunction of old and youthful bodies—aging breasts on a young torso, with sagging legs beneath a taut frame—spoke of collapse, putrefaction and renewal.

Song Dong is known for his innovative conceptual videos and photography that reveal the changes in modern China and express his response to the country’s rapid development while retaining a spiritual connection to the past. The centerpiece of Song Dong: Dad and Mom, Don’t Worry About Us, We Are All Well was the large-scale installation “Waste Not,” comprising thousands of everyday items collected by the artist’s mother over the course of more than five decades. The project evolved out of his mother’s grief after the death of her husband and follows the Chinese concept of wu jin qi yong(“waste not”) as a prerequisite for survival. Vitrines full of dried soap and stuffed with cabbages created a powerful metaphor for the effects of radical change and social transformation on individual members of a family.

In part, the chaos of the Kiev Biennale was the result of the Ukrainian government’s failure to provide its half of the funding on time. (The other half was provided by corporate sponsors and private individuals.) The government seemed to hope that their involvement would fortify their claim to join the E.U., but the country’s problems with human rights make that far from certain. Catching David Elliott in the bar after the opening, I asked if he thought there’d be another such event—after all, there needs to be at least two to warrant the use of the term “biennale.” “Who can say?” was his enigmatic response.

The First Kiev International Biennale ARSENALE 2012 ran from May 24 to July 31,www.artarsenal.in.ua

-

UNDER THE RADAR

UNDER THE RADAR Pearblossom Hwy

MIKE OTT’S PEARBLOSSOM HWY REACHES for reality, in a real way, sort of.

LA filmmaker’s Mike Ott’s last movie—LiTTLEROCK (2010) was a surprise smash in indie terms, racking up the kewpie dolls at LA’s AFI Fest, indie fests in Boston, Reykjavik, and Montreal and the Independent Spirit and Gotham Awards—the latter included a limited commercial theatrical run in NYC. Eventually the moody low-budget feature was picked up for DVD distribution by Kino Lorber and instant streaming on Netflix.

That’s a helluva act to follow, and expectations have been riding high for Ott’s follow-up, Pearblossom Hwy, which had its North American debut at the AFI Fest in November and is currently making the rounds of the festival circuit. A sequel of sorts, Pearblossom seems to pick up with the two main characters of LiTTLEROCK—Japanese tourist Atsuko/Anna and SoCal white-trash stoner Cory—a couple of years down the line, but still stranded in the buttcrack of the Antelope Valley.

At least Cory seems to be the same character—though he seemed to have a dad in the earlier movie—the latest hinges on a road trip to reintroduce him to the man he believes to be his biological father. Atsuko is now an immigrant reluctantly studying for her citizenship test, and has picked up considerably more English than the none she conspicuously spoke in LiTTLEROCK. Several ofLiTTLEROCK’s strong support cast—Roberto Sanchez for example—show up in other roles inPearblossom.

Fans of LiTTLEROCK might find this slightly disorienting, but it’s really just the first level of a complex and rewarding indeterminacy at the heart of Pearblossom’s successful simultaneous embodiment of bleak alienation and heart-rending humanism. Not to mention a healthy dose of hilarity—usually accompanying Cory’s attempts to fend off or cope with the demands of the square world. His attempts to make something of his life are pretty much limited to compiling a rambling, drug-fueled audition tape for a reality show called The Young Life, and jamming with Cory & the Corrupt, his death metal band.

The deeper ambiguities of identity and authorship are embedded in Cory’s recurring video diary sequences, where he talks about his history, family, sexuality, and ambitions, or recites fragmentary poems and song lyrics. These were generated when Ott gave the actor Cory Zacharia a camera and told him to start recording whatever was on his mind, which—over the course of several months—added up to over 100 entries. The cream of the crop are dispersed along the story arc, as the character Cory Lawler confronts his feelings about his domineering older brother and absent father, and explores his ambiguous sexual orientation—until close to the end, when the director’s offscreen voice interrupts one of Cory’s monologues to ask “Are you talking about your real Dad or talking about your Dad in the movie?”

Atsuko’s blurred boundaries are subtler, if no less compelling. Luminously portrayed by screenplay coauthor Atsuko Okatsuka, the character draws heavily from Okatsuka’s life experiences, though she was careful to point out at the after-premiere Q&A “I’ve never actually been a prostitute.” The character Atsuko finds herself engaging in the world’s oldest profession in between working in her uncle’s tree nursery and boning up for the green card exam. Profoundly isolated, she’s trying to save enough money to return to Japan to see her ailing, beloved grandmother. Most of her dialogue is conducted over the phone with her grandmother or with a bemused but sympathetic Japanese john, rather than with her ostensible best friend Cory. Their greatest moment of intimacy occurs in a repertory theater, as both cease any effort to communicate and stare at the screen, enraptured by Chaplin’s The Kid.

Pearblossom Hwy manages to up the ante for the new wave of DIY auteurism that LiTTLEROCKexemplified, and it’s no coincidence. Ott’s seat-of-the-pants semi-improvisational approach has often (and rightly) been compared with that of John Cassavetes and Robert Altman, but Pearblossom is a declaration of affinity with a cinematic canon at once more respectable and more troubled: La Nouvelle Vague.

To signal his intentions, Ott quotes the cartoonish gunshot effects that punctuate the soundtrack in Godard’s 1966 lo-fi masterpiece Masculin F&eactue;minin—a notoriously episodic and technically anti-virtuosic (or at least anti-craft fetishistic) slice-of—The Young Life of Paris, studded with scenes of ill communication. With Cory Zacharia as the new Jean-Pierre Léaud, Ott updates Godard’s bleak survey to address the contemporary phenomenon of digital globalization, and its border-dissolving impact on our understanding of reality, fiction, and self. At its core, though, Pearblossom Hwy is riddled with a redemptive humanistic compassion beyond Godard’s capacity, leaving us strangely hopeful, in spite of the darkness of Ott, Okatsuka, Zacharia, and company’s vision of the American Dream.

-

Death and Glory

I visited the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens while its current exhibition, “A Strange and Fearful Interest: Death, Mourning, and Memory in the American Civil War,” was being installed. I’d be tempted to call the Huntington a “peculiar institution,” had that phrase not already been coined as a euphemism for slavery in the pre-Civil War era. Let’s just say that, at least in Los Angeles, the Huntington is a unique institution. It has only around half the visitors each year that the Los Angeles County Museum of Art or the Getty does, and—the unique aspect—the Huntington seems content with that. It is an unapologetically elitist institution whose exhibitions are, at their best, not blockbusters but intelligent and lucid explorations of difficult subjects. “A Strange and Fearful Interest,” mounted from the Huntington collection by the Library’s curator of photography, Jennifer Watts, is a prime example.

The title is a quotation from Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., made after an 1862 trip to Maryland to find his son, who had been shot through the neck in the Battle of Antietam. In a single day, the combined casualties were almost 23,000 men, with 3,500 killed outright. It wasn’t uncommon for family members to rush to battlegrounds lest their men lie untended in field hospitals or their corpses lay putrefying where they fell. Oliver, Jr. had suffered a chest wound in 1861 at the Battle of Ball’s Bluff and would be shot in the foot at Chancellorsville in 1863; after recuperating at home, he returned to his regiment all three times.

The exhibition title is drawn from Oliver, Sr.’s 1863 observation that “photography is extending itself to embrace subjects of strange and sometimes of fearful interest,” which is another period euphemism, this one inspired by an 1862 exhibition held at Mathew Brady’s New York gallery. Before civilians like Holmes, Sr. arrived, Brady staff photographer Alexander Gardner was at Antietam. Photography wasn’t nimble enough to compete with the sketch artists sent by Frank Leslie’s Illustrated and other publications to draw while the battles raged. The slow exposures and the bulky equipment that Gardner and his team had to deploy limited them to the battle’s aftermath, which included not only nature blown to splinters but the dead where they fell. Because unmoving, the corpses were a subject as irresistible as it was horrific.

And these pictures of the dead were included in Brady’s exhibition. The Huntington exhibition has a separate room, its walls a deep purple-black, devoted to Antietam photographs that Brady displayed. Whereas the public knew published sketches of battles were impressionistic fictions, these photographs were unassuageable facts. The New York Times reported that it was almost as if Brady had “brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets”; repulsive as they are, the newspaper admitted, the pictures have “a terrible fascination,” making it hard to turn away. Such photographs sold briskly throughout the war, as the Huntington acknowledges by displaying album pages of them.

Alexander Gardener, Completely Silenced! Dead Confederate Artillery Men, As they lay around their battery after the Battle of Antietam, September 1862 More than any other single revelation, these photographs contradicted the dreams of glory with which the war had begun, the vision of men leading a cavalry charge with swords drawn. The Civil War was the first in which the slaughter had become mechanized. At Gettysburg the year after Antietam, the casualties more than doubled to 53,000, in three days. North and South alike had thought the war would be concluded within months rather than the years for which it dragged on, ultimately taking a toll, between the carnage and the disease, of more Americans than all other wars from the Revolution through the Korean War combined.

The Huntington exhibition abounds in all the media by which images were distributed during the war, from a crude wanted poster for the Lincoln Conspirators to a “line and stipple artist’s proof” of a John Batchelder print after an Alonzo Chappell painting, from published sketches of Antietam battlefields copied from photographs to a collage of printed, handwritten and photographic material exposing the Confederate brutalities inflicted on prisoners of war at Andersonville. The Bowie knife with which assassin Lewis Powell attacked Secretary of State William Seward is also on display. But in both their numbers and their effect, it is the photographs that predominate.

Lithographs of A Soldier’s Grave or Lincoln’s assassination illustrate the artistic liberties taken in that medium; the grave scene is greeting-card maudlin, the assassination an image showing Lincoln shot in the wrong side of his head as Booth performs a plié leaping onto the stage. Photography, on the other hand, contained the dialectically opposed realities of the war. Besides being the public acknowledgement of the shocking human toll the war took, photography provided the private mementos that soldiers and their families cherished–the pictures of themselves that men left behind or of their wives and children that they carried into battle tucked inside their uniforms. Each of these functions, both as concrete documentation of mass destruction and a reminder of personal sentiments, reinforced the other. Each threw into relief the other side of the contradiction—the death grip—in which the entire nation was locked.

Unidentified tintypist, Portrait of Mrs. Frederick (Marie) Ockershauser, c. 1861, Images courtesy of Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. The exhibition is rich in examples of the second type of photograph as well as the first. An unknown drummer boy in an 1863 daguerreotype stands behind his mother with his hand on her shoulder. His is a standard pose, but one customarily assumed by a husband with his wife, suggesting that this boy must now be the man in his family. Or consider Frederick Ockerhauser’s tintype of his wife. She had embroidered the leather slipcase that protected the portrait when he took it with him to the war, but only the cased tintype came back home again.

As either a document or a memento, a photograph is a stoical object. As if to countermand his father’s characterization of photographs of war as “strange and fearful,” Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. characterized the experience of war as “horrible and dull.” The latter term suggests the slogging repetitiousness of campaigning. Like photography, language was affected by the war. American prose was transformed forever, as Gary Wills has pointed out, by a three-minute speech Lincoln gave at Gettysburg. But in the short term, I wonder whether the war didn’t degrade language as well—whether speech itself didn’t become a kind of mechanical device, one more like a gun than a camera.

The coup de grace delivered to the Confederacy came from repeating rifles issued to Union troops, an innovation that increased exponentially the murderousness of combat. It’s odd how pointlessly repetitious some last words noted in the exhibition were, too. When Booth was caught and shot by the soldiers dispatched to hunt him down, his last words were, “Useless, useless”; and when his accomplice Powell was caught, he screamed, “I’m mad! I’m mad!” Then there’s the refrain to which Walt Whitman was driven when he tried to sum up the war in 1865: “the dead, the dead, the dead, the dead” was all he could say. The war was so horrible that it left people gibbering, or speechless. Only photographs could tell the horror of it all without being injured by the telling itself.

Just as the ubiquity of pornography in our own age has numbed our ability to respond to the nude figure in art, female or male, so has tabloid sensationalism deadened our response to death itself after seeing in the news media bodies ranging from victims of automobile accidents to the victims of genocide. The value of the Huntington’s exhibition is to remind us of a time when photography of a certain kind was new and the shock of such images had not yet worn off. The exhibition re-contextualizes for us not just the photographs, but shared emotions they evoked for which we no longer have a reference or even, perhaps, a capacity.

-

All over the map

Early in her career, Joyce Kozloff gained prominence on both coasts. Here in Los Angeles, as one of the organizers of the 1971 protest of LACMA’s white-male-dominated exhibition record, she became an early proponent of feminist art. Four years later, she joined Miriam Schapiro, Bob Zakanitch and a handful of other artists to found the Pattern and Decoration movement in New York. In the late 1970s, Kozloff crossed the high art/low art divide when she began painting on tiles instead of canvas. She went on to spend two decades engaged in public art, creating tile-based walls, plazas, and subway stations across the United States and abroad. (Southern California readers will be most familiar with her tiled plaza las Fuentes in Pasadena and her metro stop at 7th and Flower in Los Angeles.) Kozloff segued from public art back to studio work, using maps to make powerful political statements about imperialism and warfare. Most recently, she has turned her eclectic, trans-media eye to Chinatown kitsch, the Ebstorf Map, and vintage French school maps.

Kozloff has been exhibiting regularly, to remarkable critical acclaim, for more than four decades. I spoke to her twice, in July via telephone from her New York studio and September when she came to CB1 Gallery in downtown LA, where she has a show planned for January–February 2013.

BETTY ANN BROWN: Kozloff may be best known as one of the founders of the Pattern and Decoration Movement. I ask her to speak about it.

JOYCE KOZLOFF: It was New York, 1975. Miriam Schapiro invited me to a meeting at Bob Zakanitch’s loft. There were several other people there, including art writer Amy Goldin and artists Tony Robbin and Robert Kushner. Later, there were more meetings and more people joined us.I was excited about two discussions in those early meetings: one, that we were defining ourselves in opposition to the dominant minimalist style; and two, that all of us were exploring the impact of non-Western art.

When we began getting a lot of attention, I went around the country giving lectures on the movement. Often, there were weavers and potters in the audience. I thought we were paying homage [to their art forms], breaking down the barriers [between high art and low art]. But again and again, they said, Yeah, but you’re still making paintings. Why don’t you weave baskets? Or whatever.

I heard it so many times. Then one day I really heard it and decided I must begin working in the decorative arts. I couldn’t justify the ideology of breaking down the hierarchy by simply incorporating decorative motifs into painting any longer.

Joyce Kozloff, Social Studies: La Chine, 2012 I point out that she paints now.

I’ve always painted. Whether I paint on tiles or on canvas, the brush has been my primary tool. However, I stopped painting on canvas in 1977 and worked in other media for 20 years. Now I paint on canvas. I also paint on panels, paper and fabric. I draw and do collage. For me, there are no hierarchies among media. I don’t call myself a painter. I call myself an artist.The recent, more politically engaged work has a different kind of content than the pattern-based work of the 1970s and ’80s. I ask Kozloff to talk about that shift.

I’ve always been a political artist. For me, the decorative work was political and provocative. People are not offended by it now, but they were at the time.I sent my first decorative painting [Three Facades (1973)] to [New York gallerist] Tibor de Nagy and he hung it in a back room. One day, he told me Clement Greenberg had been in and said it looked like ladies’ embroidery. Tibor’s hands were shaking and his voice was quivering when he [told me] this, and he sent the piece back to my studio. Tibor exhibited the painting once he got used to it, but at that time, Greenberg’s formalist ideology was still quite powerful.

Kozloff focused on public art from 1983 through 2003. I ask her what initiated the move from public art back to the studio.

When I was doing public art, I hand-painted all the tiles. Each project would take over my life for a year. Meanwhile, I had other ideas, but I never had time to get to them…For every public art project, I was given floor plans or blueprints of the site. I saw the plans as the scaffolding of the building; the art I layered onto them was the skin. One day it occurred to me that this could be an interesting process for my private work. Soon after, I began to copy city maps from atlases, weaving into them ideas and images that I associated with those places.

Joyce Kozloff, Europe (detail), 2012 The mapping work takes time. If you’re an MTV person, you may not get it, because you may not spend enough time with it.

I’ve seen people come into one of my shows, where there’s a lot of very, very dense work, glaze over and walk out. Other people will stand in front of each piece and really look at it.We’ve grown up thinking that political art looks a certain way, black and white, or expressionistic and harsh, and my work isn’t like that. Unless you come up close, you may not even see the politics. It might look pretty or decorative—that’s my aesthetic—so there’s something dissonant there.

I ask Kozloff about China is Near (2010), which exists as original artworks and a related book.

I was planning to travel the Silk Road in China with two friends, but my brother became terminally ill and I didn’t want to be far away. So I started walking to Chinatown, which is a few blocks from my house.The title of the series comes from Marco Bellocchio’s film La Cina é vicina, which is not about China but about Marxists in Rome. My own work is not about China, but about Chinatowns.

I began by copying maps of the Silk Road out of books—the books I had bought for my travels. I added collage elements like cut-tissue papers from China. Then I bought my first camera—I never took photographs before and don’t know if I will again—and shot the pictures in Chinatown. And I downloaded and printed from Google maps all the places in the world called China. The series is a combination of collage, drawing, photographs, and those Google maps.

I mention Barthes’ Empire of Signs, which is about the Western idea of Japan, just as her work is about the Western idea of China.

I loved Barthes’ book. I also read about Chinatowns when I was doing the series. Chinatown as a concept was invented in San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake. The Chinese community wanted to make something that would be commercially viable and deter discrimination. It was a big success. And it’s been copied all over the world. Someone told me they’re making a Chinatown theme park in China now.China is near. China is everywhere.

Joyce Kozloff, China_Michoacan_Mexico, 2010 I ask her what came after China is Near.

I did this big painting JEEZ (2012). Marcia Kupfer, an expert in medieval maps, spoke to me about the Ebstorf Map. The original was 12 feet in diameter, so I made my piece at that scale, in 36 two-foot square sections. I quickly realized that the body of Christ was embedded in the map. So I Googled Jesus images: Jesus gay, Jesus Asian, Jesus African, Jesus as a woman, and a plethora of stuff came out. Ultimately, I added over a hundred images to the piece—everything from Old Masters to kitsch. I loved working on it; I think it’s very funny.I ask her how it felt to work on Jesus, since she came from a Jewish background.

In my hometown, we were practically the only Jewish family. Everyone else was Catholic. When I started working on JEEZ, I thought, oh my God, this guy has been with me all my life, everywhere I looked. My first love when I started studying art seriously was the Italian Renaissance and there’s a preponderance of Renaissance imagery in JEEZ. I didn’t do justice to it. But I certainly didn’t degrade it.The piece is also my response to what is going on politically in this country. The escalating rhetoric of religion in our political life is disgusting to me, particularly the imposition of Christianity. Jeez was my way of dealing with that.

Finally, the most recent body of work, Social Studies.

I found these French school maps at a flea market in Paris. They were printed in the 1950s and early 1960s. They depict different countries and continents, as well as different regions of France. They’re very charming, with animals, plants, factories, and people on them.This summer, I worked with Fran Flaherty in Carnegie Mellon’s new digital print lab. We scanned the existing maps and layered new content onto them. I wanted to introduce subjects that might not be taught in geography or history classes, and to question the way children are educated. There’s information about elections, about history, about native populations, about natural resources, about wars. There are 17 in the series. We printed them digitally, at 36” x 30” in editions of five each.

The series is rich and dense, a great way to pictorialize the intersections of history and geography. I ask her where the work will go now.

Who knows? I may take the school maps in a completely different direction.Who knows, indeed? With an artist whose vision ranges over such large, complex territories, there is no way to predict where Kozloff’s oeuvre will travel next.

Joyce Kozloff in her New York studio. -

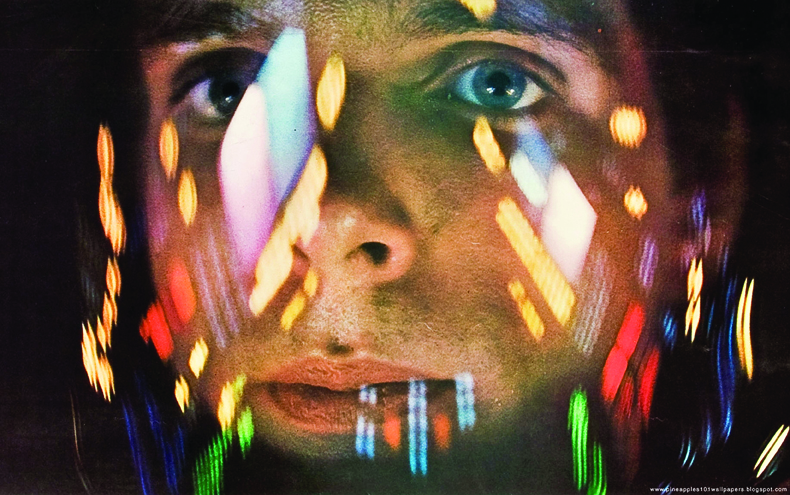

Seeing The Big Picture

Stanley Kubrick’s filmmaking career begins and ends in a mood of urban claustrophobia—at its earliest stages, gritty and almost inarticulate, yet full of expression; at the end, almost hyper-articulate yet inchoate; refined, even rarefied, yet darkly, mortally carnal, unfolding its waking-unconscious narrative in a space that is as simultaneously closed and expansive as its protagonist’s mind. Over the course of 50 years of developing and directing films, Kubrick was to open and physically amplify those spaces, casting ever wider lenses in every direction to the sky and beyond.

Many of those same lenses are displayed in a vitrine in Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s “Stanley Kubrick” exhibition, which originated at Frankfurt’s Deutsches Filmmuseum. Although they may be of more interest to film professionals, they are not incidental here. At the risk of legitimizing a battered and near-meaningless phrase of some currency in media circles, no one understood the “optics” of a situation—in every sense—better than Kubrick did. Beyond understanding how perceptions were shaped was his understanding of how every aspect of their representation shaped story and outcome. Whether in a chiaroscuro, half-tone world of black and white and hazy grays, or sanguineous and richly saturated color, Kubrick’s films show us matters of sense and sensibility trumping abstract notions of order, perspective, control, belief; the whole contained and magnified by the story moving across the screen. What remains consistent through these very distinct films, is a preoccupation with the juxtapositions and intersections of interior and exterior spaces, and parallel to that, physical and psychological spaces. In Kubrick’s movies, we are always acutely aware of how where and what the characters see condition the way they see, and vice-versa.

Kubrick’s gift for grafting a dramaturgy of space and perspective to the dramaturgy of script and performance was unique. There is a stunning economy, almost bluntness, of character development evident from the earliest of Kubrick’s films to the very end. Kubrick understood the craft of photo profile and essay from his years as a staff photographer for Look magazine; and there is a quality at the core of several, if not all, Kubrick films that hearkens back to magazine-style photojournalism. Kubrick uses the body language of the characters in relation to their space to both articulate character sensibility and development and their relationships with each other. The characters in Killer’s Kiss (1955) might be shadow puppets. The dialogue and character exposition range from the schematic to almost hilariously blunt to psycho-absurd; but, in almost perfect sync with gesture and movement, the film story holds us with its drive and urgency.

In Paths of Glory (1957), set against the backdrop of World War I, human conflict is plotted out against variously social, ceremonial, strategic and mechanical spaces. In the opening scene, set within the drawing room of a grand chateau, Kubrick choreographs one general cagily circling (and ensnaring) another in what amounts to a martial minuet, as they discuss a maneuver that will cost the lives of hundreds of their soldiers. The forthright Colonel Dax (Kirk Douglas) does not linger in this space—or any other—but, framed by barracks and trenches, moves relentlessly forward into a backtracking camera.

Breaking Lolita (1962) out of the head of its narrator, Humbert Humbert, involved similar cinematic choreography—counterpointing Humbert’s interior monologue with his various pas de deux and trois with Lolita, her mother Charlotte, and the enigmatic Clare Quilty. Here (as if the screenwriting services of Vladimir Nabokov were not enough), Kubrick was aided by another kind of cinematic trick: genius casting. In addition to Sue Lyon’s revelatory performance in the title role as an American suburban “nymphet,” and the note-perfect performances of James Mason and Shelley Winters in the roles of Humbert and Charlotte, Kubrick was afforded the services of another genius, Peter Sellers, as the chameleon Quilty. From Quilty’s disheveled mansion to suburban interiors and backyards, to the open road, to the revelation of the character of Lolita herself, Kubrick foregrounds frank yet guileless American corruption against a receding horizon of betrayed idealism and false (European) cultural pretensions.

Kubrick would deploy Sellers for another triple impersonation in Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964). Here, Kubrick shows us a ship of state turned ship of fools, a synoptic view of man’s fate rendered tragic-comically absurd. Sellers is variously angel/handmaiden to the incapacitated (as Mandrake), agent of inefficacy (as President Muffley), and agent of doom (Strangelove). In the Ken Adam-designed War Room with its halo of light bathing the circled desks and soaring raked walls with strategic maps tracking SAC deployments, as the world closes in on its masters, Muffley dissolves into the light, while Strangelove wheels around seemingly out of nowhere—an anti-Christ manifesting from the void—the same void through which Slim Pickens as Major Kong will ride his nuclear warhead to bright oblivion.

The troubled spaceship, “Discovery 1,” in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), under the stewardship of another dubious (and similarly constituted) trio, might be considered another kind of ship of fools. Here, within astonishingly realistic sets, including a rotating centrifuge, Kubrick documents the tasks and activities of his astronauts Poole (Gary Lockwood) and Bowman (Keir Dullea), including their interactions with the HAL-9000 computer (voiced by Douglas Rain) through which, in tandem with earth-based command operations, virtually all of the vessel’s functions are managed and run.

But within the arc of Kubrick’s Odyssey, which after all takes us back to the dawn of humankind and fast-forward (via “stargate”) to another sort of dawn, Discovery’s troubles amount to a sideshow—however elaborate and richly informative, critical to this particular dramaturgy of space.

In 2001, the human relationship to space—from the microscopic to the cosmic—would seem to be at the heart of the film’s subject matter. But more central to Kubrick’s concerns here are the ways humankind orders space, our extensions into space, and the attenuation of our relations to these extensions over time and distance—and by implication, to each other.

There is a break here, left unresolved by Bowman’s emergence into the Louis XVI-classical space of his observation chamber, his transfiguration via yet another vessel—the “amniotic” sac of the Star Child.

Some of these issues are foreshadowed in Kubrick’s earlier films: the inventory and ordering of human thought; the protocols seemingly dictated by mechanistic feedback. (E.g., in Strangelove, the operation of the Doomsday Machine; Muffley’s attempt to placate the Russian premier’s inebriated pouting at the protocols of the hotline: “Of course I like to say, ‘hello,’ Dimitri.”; Mandrake’s desperate attempt to tease out the return command code.) Kubrick would weigh these issues in another far more dystopic futuristic context in his film based on Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange (1971). More than Kubrick’s preceding (or later) films, the surrealistic visual style of Clockwork is identifiably of its time (though as always, Kubrick is ahead of the pack—consider that Scorcese’s Taxi Driver was released five years later). Here, a swinging welfare state incarnation of the U.K. (tailor-made for a Thatcherite campaign ad) is the backdrop for a counterculture of wanton gratification and sociopathic violence amongst a balkanized but empowered welfare class with time on its hands and vivid comic-book imaginations.

Without setting aside concerns central to his prior films, in Clockwork, Kubrick moves beyond a straightforward spatial choreography to a fluid and versatile style beautifully adapted to the post-Pop landscape that had evolved between the time Burgess published his novel and when filming began. In Clockwork, Kubrick has already leapt beyond that landscape to what we now recognize as Postmodernism. Its influence can be seen in everything from music video to Japanese anime to (in its lowest common mass-dilution) Apatovian freaks, geeks and superannuated lost boys.

Although Kubrick yearned to return to the “big canvas” of a historical picture, his difficulties financing a long-planned Napoleon project, turned him toward a more intimate novel set against the panorama of 18th-century Britain and Europe, William Thackeray’s Memoirs of Barry Lyndon, Esq. Here, Redmond Barry’s progress from Irish adventurer to baronial seat to forlorn exile unfolds against landscapes and interiors deliberately intended to evoke Gainsborough, Chardin and Menzel. Adapting lenses used by space discovery missions to cameras once used for background film, Kubrick shows us the world Barry sees and moves through—in natural light, the filtered daylight from the windows of high-ceilinged great halls, and candlelit drawing rooms. There are no feints or sideshows here. Kubrick has even substituted a narrator for Barry’s first-person voice. Instead, the pictures are allowed to tell the entire story—set magnificently to music by Bach, Mozart, and, most famously, the Handel D-minor Sarabande and Schubert E-flat piano trio. Music literally underscores what Kubrick commits and resigns us to—Barry’s quest for some purchase on his fate and his inexorable surrender to it.

Barry Lyndon is a pivotal moment in Kubrick’s career—as dark as its candlelit salons. In no other Kubrick film are we left with a comparable sense of the futility of human agency. Even Jack (Jack Nicholson) is ultimately recomposed into the “big picture”—repossessed by the world of the Overlook Hotel in The Shining (1980). Private Joker (Matthew Modine), the reluctant killer, survives and moves on, his humanity marginally intact, which, in the context of Full Metal Jacket (1987), is saying a lot.

LACMA’s Kubrick exhibition sprawls between the foyer and the adjoining plaza-level galleries of its Art of the Americas building, but has a resonance and coherence that accords with the issues and concerns that thread through these very distinct pictures. Walking between the installations built around various props, stills and transparencies, clips, documentation and paraphernalia, the viewer has the sense of moving between rooms marked by formative incident or heightened awareness—which is true to the experience of the films. Caught up in the dramatic and affective themes and motives of the individual films, we may be less conscious of what they present in their totality—which is nothing less than a history of late 20th-century consciousness.

S

-

DON’T TOUCH ME THERE

Love, longing and performance art are best experienced in their natural habitats of dark venues on the edges of civilization. “UNTOUCHABLE,” curated by Italian performance artist Franko B, proved just that in November at The Flying Dutchman pub in Camberwell, London with an evening of performances on the 17th. The event doubled as a fundraiser for the Southwark LGBT Network and a platform for new live and visual art pieces to be exhibited in an informal setting. The familial vibe, the constant presence of Franko’s two Jack Russell terriers, and the unabashed evidence of sex club accoutrements throughout the venue—including purple walls and a series of pull points on the ceiling, walls and floor—seemed to invoke an openness in the audience to participate in some of the more intimate performances.

The opening night and private viewing focused on visual art, including: stunning woodcut portraits by legendary tattooist, Alex Binnie; videos by Julie Tolentino, Kyrahm and Julius Kaiser, Massimo Mori, and others—and photos of Ron Athey’s 50th birthday performance, Self-Obliteration, in New York two years ago. A recurring thread of playful yet often darkly cynical themes ran throughout the exhibition as seen in David Bo’s pile of brightly colored cartoon genital pillows, each slightly differentiated through line drawings of varying stages of pubic hair. One of the more startling pieces was Christina Berry’s tragi-comic, Dead Pets, which involved two hollowed-out cats suspended on tiny domination racks, their furry torsos corseted and laced while stitched leather organs extended from their sad, deflated nether-regions.