YOU CAN TELL A GOOD DEAL ABOUT AN ARTIST FROM his studio. After I arrive at Mark Wallinger’s, in the buzzing heart of London’s Soho district, he pops out to buy a couple of cappuccinos before we settle down to do the interview, giving me a chance to nose around. His bookshelves contain an erudite mix, with the poems of John Ashbery wedged between James Joyce’s Ulyssesand Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom. Pinned to the walls are a couple of photographs of ears (left and right) and Rilke’s famous quote from the Duino Elegies: For beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror which we are barely able to endure.” There are photocopies of Velázquez’ scarlet-clad Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1650) that Wallinger used for his piece, I am Innocent” (2010)—an investigation into religious authority.

Reproductions of Titian’s Diana and Callisto and The Death of Actaeon (based on Ovid’s Metamorphoses) reference his most recent project at The National Gallery, part of an exhibition of contemporary responses” to the master, Metamorphosis: Titian 2012.” This exhibition reunites those two paintings for the first time since the 18th century. We also see works by leading British artists Chris Ofili, (up for the Turner Prize) and Conrad Shawcross, along with those by Wallinger for designs they created for newly commissioned Titian-inspired ballets at the Royal Opera House. These, in turn, generated scores by some of the country’s leading composers, as well as a collection of Titian-inspired poetry, with contributions from Seamus Heaney, Tony Harrison and Poet Laureate Carol Anne Duffy. At the National Gallery Wallinger built a sealed room where the viewer was turned into a voyeur, a veritable Peeping Tom, encouraged to peer through broken glass panes and keyholes to catch a glimpse of a woman washing. There were fears it might encourage the heavy-breathing brigade. How long did his “Diana” have to be confined in this sealed gallery room, I ask. Oh, there were several of them working two-hour shifts,” he volunteers. Apart from Metamorphosis” it’s been a hectic year; he has had recent shows at the Baltic in Gateshead and at the new Turner Contemporary in Margate.

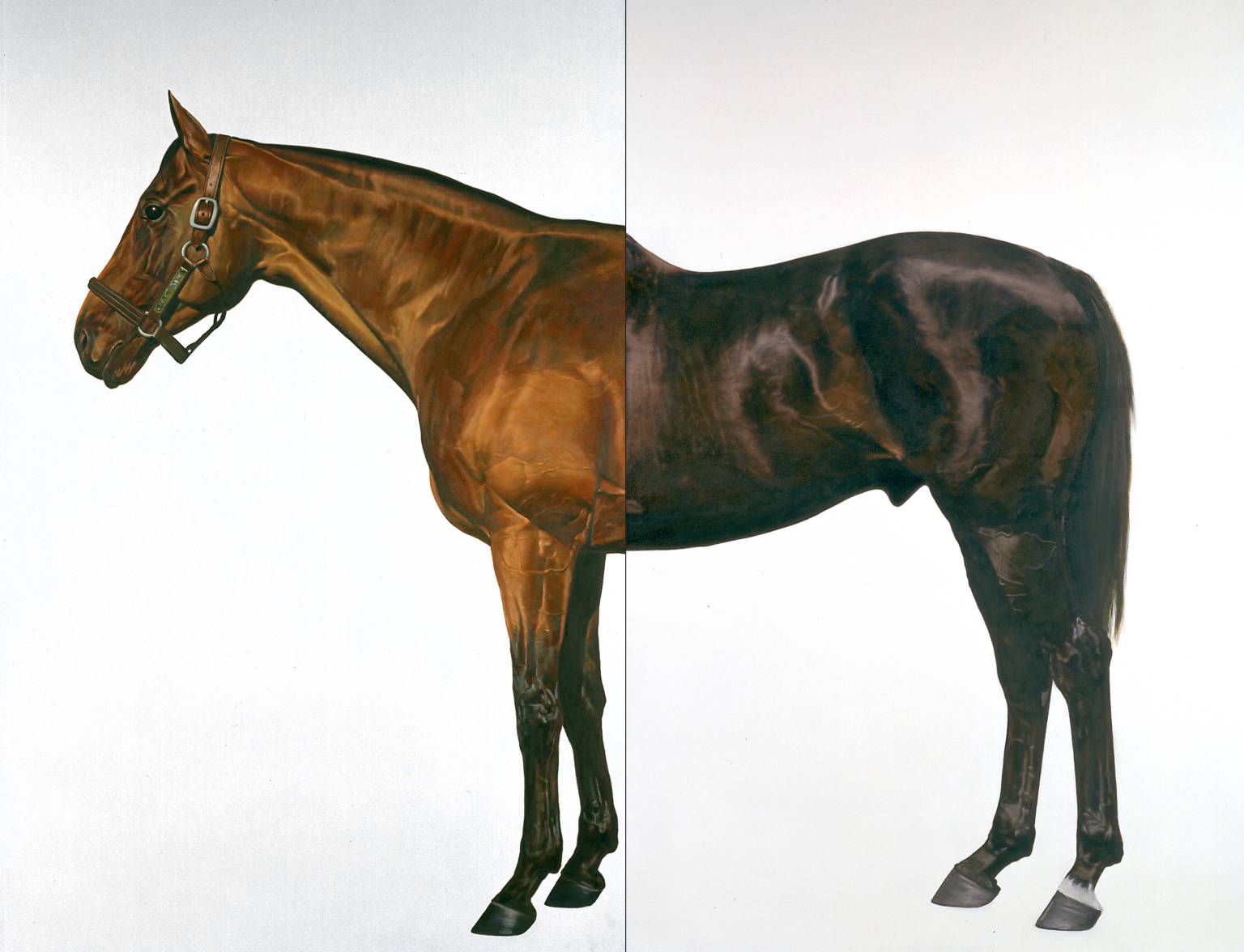

Since leaving his MA course at Goldsmiths College in 1985, his career has been on an upward trajectory. In 2004 he spent 10 nights in the Berlin contemporary, the Neue Nationalgalerie (he was living in the city at the time), dressed in a bear costume (the symbol of the city is a bear). After that he went on to produce a series of technically adroit oil paintings of the homeless and race horses (racing is a passion) and created the only religious public statue to appear in England since the Reformation, his life-sized Ecce Homo, a proletarian Christ created as part of the ongoing series of sculptures for the empty fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square. Then in 2007, he won the Turner Prize for his audacious recreation of the protest camp erected against the Iraq war outside the Houses of Parliament by the British peace campaigner, Brian Haw. Wallinger had been photographing Haw for a year before he made the piece and enjoys the irony that what was seen as an eyesore and an embarrassment in Parliament Square was worthy of a prize and serious critical analysis when placed in the marble Duveen Hall of Tate Britain. I mention Duchamp and how the gallery context defines a piece as a work of art.” Yes, there is a similarity,” he agrees, but Duchamp used readymades and this was a reconstruction.” In 2008 he went on to win the prestigious competition to erect Britain’s biggest figurative artwork, a giant white horse to welcome visitors on the Eurostar in Kent. But, for the moment, with the recession, it has been put on ice. And then there was a major monograph simply titled Mark,” published by Thames and Hudson.

As we settle down with our coffee I ask if he always wanted to be an artist. Ever since I was a kid,” he says. That’s really all I wanted to do. I spent a lot of time drawing. It was something of my own.” Did he have any idea what contemporary grown-up” artists did? Probably not. I just did what I was good at, what absorbed me, though as a child my parents took me to the National Gallery and the Tate.” Born in semi-rural Essex (just outside London) he came from a politically aware, left-wing family. His father protested in 1939 against Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists in Cable Street, a Jewish quarter of the London’s East End. Not moneyed, his parents nonetheless valued education. A clever kid, he got top grades at school and could easily have gone on to university. Instead he did an Art Foundation course at his local technical college. It was hard living at home when all my mates had started university.” But by 1986, at the age of just 26, he was having his first solo show in London, Hearts of Oak,” at the Anthony Reynolds Gallery (Reynolds remains his dealer). There, under the title Where There’s Muck There’s Brass” (an old Yorkshire expression eliding the notions of shit and money), he showed a painting that appropriated Thomas Gainsborough’s 1750s double portrait Mr. and Mrs. Andrews, which he executed on plywood sheets appropriated from Collet’s, the leftist bookshop on Charing Cross Road where he worked, in order to explore issues of the English class system during the Thatcher years.

Although he attended Goldsmiths, the college that under the tutelage of Michael Craig Martin produced most of the YBAs, Wallinger’s work sits outside the ironic posturing of much of that group. Older by a number of years, his attitudes were minted in the hardcore political years of the 1970s. At college he came across a number of books that would be seminal to his intellectual and artistic development: Joyce’s Ulysses, on which he wrote his thesis, E.P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class(1963) and John Barrell’s The Dark Side of the Landscape: The Rural Poor in English Painting 1730-1840 (1980). Always interested in issues of social injustice, he didn’t, he says, get along well with authority. Does he, I ask, see himself as an issue-based artist who reaches for metaphors rather than playing with ironic conceits? For me art has to have a certain ambiguity that keeps it alive. One of the reasons I stopped painting was because I was using painting rather than making paintings. As a painter there was no place to go. It’s easy to get trapped by your own facilities and the weight of art history. History has got painting by the throat. The work was becoming too arch. I wanted to make work about being in the real world. There’s something a bit antediluvian about spending one’s time stretching canvases and squeezing paint. I like art that’s democratic, that suggests you, too, can do this.”

Myth and religion seem to have an important role in his work, I suggest. Well,” he says, I had the idea for Ecce Homo whilst on the phone. It was almost instant. It was, after all, the millennium and no one was mentioning Christ, which seemed a bit odd. I wanted to know how much residual connection there still was in this country with the Christian tradition. I liked the idea of the vulnerability of the piece standing alone on its plinth in Trafalgar Square, a place that has seen many political protests.”

I wondered if age and success have changed the way he makes art. You build up a body of work by following your nose and gravitate towards certain themes and intellectual ideas and just hope that you’re not getting worse!” he answers. I’m in the business of asking questions. I am not interested in being didactic. I don’t bring a signature style to what I make. As to success, well, I spent two years working on Metamorphosis and was paid £5,000. So it’s not riches.”

So what is important to him? That a work has impact, beauty, poetry, truth.” That sounds a bit like an old-fashioned romantic, I suggest. He laughs. But I also have to enjoy the function and rigor of the piece.” Having abandoned painting he has made an incredibly varied array of work, but what underpins it all is a questioning humanity. In 2008 he created Folk Stones” for the Folkestone Triennial on the East Kent coast. Set in concrete were 19,240 numbered stones on the town’s clifftop overlooking the English Channel. It was from here that millions of soldiers left for a certain death on the battlefields of France during the First World War. Each numbered stone corresponds with a soldier who died on the first day of the Battle of the Somme on July 1, 1916. It is a powerful, moving monument, but one that does not aggrandize.

While being fully aware of the relationship between signifier and the signified it ultimately puts human compassion center stage. Here, then, is a rare artist who is unafraid of the big questions, who relishes ambiguity and whose work is open to multiple readings. In 2008 he was commissioned to place a Y-shaped painted steel sculpture resembling a tree in the idyllic Bat Willow Meadow of Magdalen College, Oxford. This poignant piece could stand as a logo for much of Wallinger’s work in that it encourages the viewer to ask the question, Why?” and then listen for the varying answers that bounce back.