Your cart is currently empty!

Category: Editor’s Letter

-

From the Editor

Sept/Oct 2024; Volume 19, issue 1 Dear Reader,

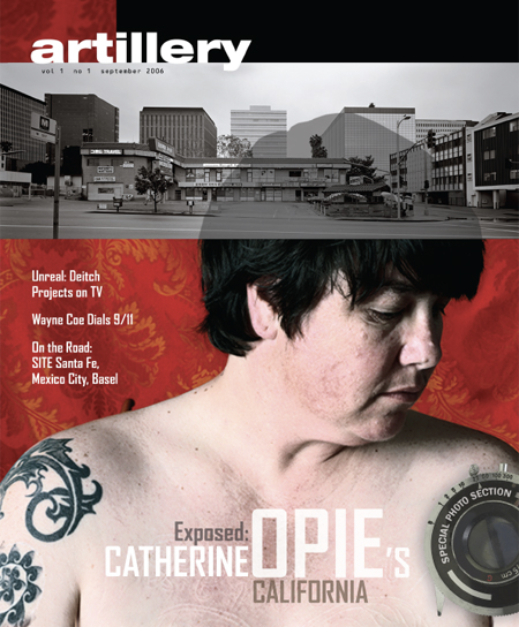

Dear Reader,I have good news and bad news. Let’s start with the bad news: This, after 18 years, is my last editor’s letter. What an incredible journey it has been. Here’s the good news: Artillery will still carry on! More on that later.

I started this magazine with my late husband, Charlie Rappleye, in the summer of 2006. This career-turn was a surprise to me, as being an editor of a magazine was never on my list of what I wanted to be when I grew up. I’ve been an artist all my life. Whether I want to reenter that world after this, is another question. After being the editor of a contemporary art magazine in Los Angeles for nearly two decades—I now feel that I know too much. I’ve seen the machinations of the art world, and it’s not the prettiest picture, certainly not one I want to jump right back into as an artist.

But for now, I’d like to reflect on that incredible journey with the art world. Back in 2006, there was a severe dearth of readable LA art publications. A few quarterly nonprofit academic art journals were in circulation, but I found them to be deadly, and most people would silently agree. I had edited the local naughty art zine, Coagula, for a year, and enjoyed that immensely: I loved publisher Mat Gleason’s unfiltered take on the art world, but I wanted something in between—something that reflected the real world of an artist, something more daring and iconoclastic. Some humor, even?

By Artillery’s third year, a new tag line was added to our logo: The Only Art Magazine that’s Fun to Read! At that point we had comics, poetry, opening-party photo spreads, reports from Gotham City. There were fleeting columns with names like Throttle, The Poseur, Outer Space, Retrospect (by THE Mary Woronov), Under the Radar, AmmuNation, Private Eye, Off the Wall—and my fave, On the Wag with Mitchell Mulholland, our gossip column that was so snarky and sardonic that I was forced to kill it in the interest of survival.

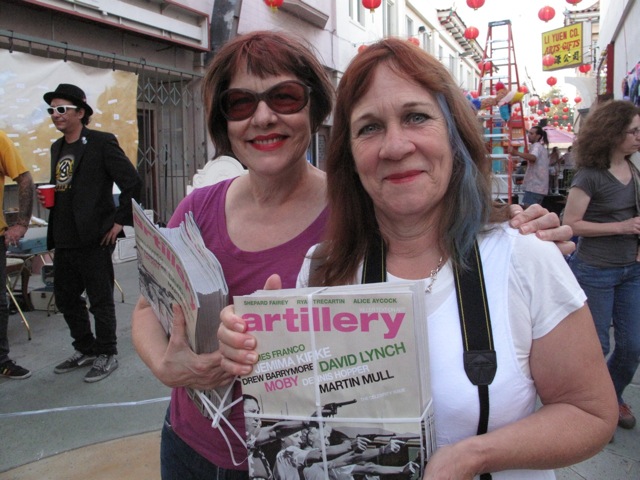

We were off to a good start: The LA art world embraced us, and we hired Paige Wery at the end of our first year. Paige had never been a publisher, but none of us had experience in running an art publication either, so we took a chance. Turns out, she was a natural and boosted the magazine to another level. We went to art fairs, book fairs, threw parties, poetry readings and art debates. We traveled to New York, San Francisco and Miami. We were a great team—certainly a highlight for me in the magazine’s early years.

Getting to know the art world through a different lens sometimes soured me. Often, it just wasn’t my scene; I felt like an interloper. Then I’d run into artists like Mike Kelley, and all the sourness would disappear. He was so real and unpretentious. At art openings he was a delight, and we would crack wise. I would routinely pester him to let me interview him and eventually he agreed. I told him I’d contact him soon.

That’s when Kelley preempted me and sent a “letter to the editor” that bitch-slapped me about being maligned in our gossip column, and he demanded we cancel his subscription immediately. He added that he was looking forward to wiping his ass with the magazine, especially the Mitchell Mulholland page.

I think we all know how this story ends. Yes, I did get an interview with Kelley, but tragically it was his last interview. He was on the cover of our January 2012 issue when he took his own life. The interview was extraordinarily profound and eerily prescient. What happened was beyond heartbreaking.

Of course, I will never be able to blot that out of the magazine’s trajectory. The irreplaceable loss of Mike Kelley seemed to take the life out of the art world for a while. Why did he do it? He was right on the edge of grand success, the kind artists strive for, having just signed on with Gagosian. But he didn’t seem to be relishing it. In our interview he kept mentioning to me how his father referred to him as a Martian.

Being an artist or even proclaiming you were an artist used to feel like being an outsider or someone on the fringe. It wasn’t as acceptable or widely embraced as it is today; it certainly wasn’t thought of as a prudent career choice. With the plethora of art schools in Southern California churning out artists who have chosen to stay in LA, Artillery found no shortage of content to cover. A few times I invited our contributors to edit a theme they wanted to delve into, and many ended up as our most provocative issues. Contributor Tucker Neel pitched a “Queered” issue back in 2011. He gleefully pointed out that our cover of New York artist Kalup Linzy was the complete opposite of LA’s other art magazine, which at the time featured Ed Ruscha on its cover. I probably don’t have to spell it out, but, uh … straight old white male vs. queer young Black artist? In many ways, I felt Artillery was ahead of its time, certainly a unique publication. We had a 2008 issue on race long before the BLM movement, and a sex issue that had clients vow that they would never advertise with us again. One coverline, Contemporary Art Hates You (my John Waters interview) had my publisher screaming, “It looks like it says, ‘Artillery Hates You’”—I secretly loved that. Our Celebrity issue with Martin Mull on the cover was sort of genius, I must admit. I truly felt our magazine was the only art magazine that was fun!

And I did have fun with the magazine, but now, I’m not having as much fun, and for me, that means it’s time to move on. I believe what I created was and is something important to Los Angeles, being a significant art center. I hope you do too. That’s why it’s time for me to go and let someone else come in with fresh ideas and shake things up a bit. My successor is Daniela Soberman, whose first issue will be November. She believes in Artillery and knows its value in a big city like LA, as I did, and knows it can grow and maintain its integrity and devotion to quality art journalism.

With that, I bid my adieu. It’s been a great ride. I cannot thank my loyal freelancers and staff enough for all their dedication, hard work and enthusiasm. Many of you will be lifelong friends—such a treasure to me. And our advertisers, you literally kept us alive with your support and belief in Artillery. I know some of you had to rob your piggy bank to pay for that ad, but you knew the importance of having an excellent art magazine. Journalism is a dying art, and I have such respect for our advertisers that wanted to reward and keep that alive. And I didn’t forget about you, Dear Reader, for we simply would not exist without you.

Lastly, Artillery carried me through good and bad times in my own personal life. I never missed an issue, even when my husband died, going on six years now. I knew it would be the only thing that could get me out of bed during that deeply dark time in my life. Charlie believed in Artillery and wanted it to succeed in every way. I want that too, and now I get to sit back and watch its legacy live on.

-

From the Editor

July/Aug Volume 18, issue 6 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,As a kid, I didn’t get to do much traveling. The family trips we took were always by car to visit relatives, somehow miraculously fitting seven of us into a big two-toned Oldsmobile. My dad used to roll down the window, just a sliver, to blow out the smoke from his cigar. On our way to Chicago, where my Italian grandparents lived, we usually passed through St. Louis. We never stayed there, but sometimes we got stuck in traffic and detoured into the city on a boulevard with shops, theaters and bright lights, with cars honking and skidding on the wet pavement in the early evening mist. I loved the handsome red-brick houses all lined up, some of them lit up with Christmas lights, as most often we were traveling during the holidays.

This is when my mom would roll down her window and sigh heavily, “I love the smells of the city.” It became a family running joke, and we teased her mercilessly with fake coughing and choking while holding our noses.

I’m with Mom: After being raised in a tiny southern Missouri town, I loved every minute in the city. Chicago, where my mom grew up, was a thrill beyond belief—Lake Michigan was the ocean, the Chicago River, a canal in Venice, and the Chicago L was better than a Disneyland ride.

This was the extent of my traveling as a youth, and I felt beyond fortunate to have had the experience; it enriched my life in so many ways. My exposure to the Chicago Art Institute played a huge part in my lifelong passion for the arts. The different cultures and diversity in the metropolis opened my eyes to a whole other world. Travel naturally elevates one’s tastes and experiences, even if it’s not that far from home.

In this issue, our Ask Babs columnist answers a reader who wonders if they should be traveling to art fairs and biennials around the world to enhance their burgeoning art career. A resounding yes, Babs replies, in a cautious manner though—she recognizes not everyone has the means to go jet-setting and suggests the next best thing: visiting websites, watching films, and reading about foreign places.

Our Summer Travels issue offers just that. New York contributor Sarah Sargent focuses on the positive in this year’s Whitney Biennial, an otherwise “meh” show. LA contributor Alexia Lewis was invited to Richmond, Virginia, to attend a ceramics arts conference where she finds the art community’s way of dealing with their glaring Confederate past surprising and hopeful. Patricia Watts takes us to Italy for the Venice Biennale; this year the art gets real. But if you’re an Angeleno just staying put, a short trip to Orange County might be worth your while. Writer Liz Goldner discovers California gold at the Hilbert Museum’s newly expanded space. The massive California scene-painting collection will certainly take you on a Golden State journey. And we invite you to take that journey with us too.

-

From the Editor

May/June Volume 18, issue 5 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,In the early Artillery days, I assigned a writer to critique the films and videos that were showing in the sprawling 2007 MOCA exhibition, “WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution.” There were more than 20 films and videos included, mostly viewed on the original, portable black-and-white television sets or small analog monitors with bulky VHS recorders and other archaic equipment. Thick black cords, oversized headphones and extraneous hardware gadgets were in full view, making them part of the dated presentations.

After seeing the massively impressive, exhaustive exhibition (full disclosure: I pretty much skipped over the videos), it dawned on me that I should return and really watch the videos, all of them, in their entirety. The low-budget (or nearly no-budget) production of most of the work provided a window into the then newly discovered medium being used in art—video.

Besides my desire to go back, I thought that others might feel the same way. (Don’t most museumgoers skip watching the entire films at big exhibition shows?) I found myself drawn to the crude videos with the grainy black-and-white closeups of women’s faces and naked body parts—usually the artists themselves—always full-frame. Contemplative observations, confessions, questions, concerns and self-absorption seemed to be a running theme in a lot of the films. But really, could I sit through all of them? Perhaps I should’ve included a rating system when giving the writer his assignment to cover the show.

There doesn’t seem to be much need for help in making those decisions these days. In this Film, Animation & Video issue, we feature six female artists that make it impossible to walk away from their moving image pieces. For one thing, it’s usually the main thing in the exhibition, filling the gallery entirely, not tucked away in a darkened side room. Technology has leaped into a big fast-forward since the days of the “WACK!” show. Although Palestinian artists Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme draw on the past for inspiration, their multichannel, multisensory films look very different from the days of the portable black-and-white TVs. But they still talk about the things that are important to them, whether personal, familial, political or emotional, as reported by writer Tara Anne Dalbow. Admittedly, there are new matters to explore 20 years later. For instance, multidisciplinary artist Ethel Lilienfeld delves into 21st-century concerns, such as “self-image and the filters that augment—or completely change—our appearances,” writes New York contributor Annabel Keenan. Lilienfeld explores our virtual selves, or rather how we present ourselves in the virtual world. Women especially fall victim to the superficiality of social media, even to the point of going to plastic surgeons with their “filtered” double as a model.

In the end, the writer finally turned in his copy on the “WACK!” show, claiming he did as well as one could in the three hours he spent watching the videos and films. He came up with a rating system, and one of the films he watched in its entirety—and claimed to have been “mesmerized” by—was 27 minutes long. Our contemporary tools make the art of creating moving images a much easier process. But the message remains the same, as you will see in these pages.

-

From the Editor

March/April; Volume 18, issue 4 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,I admit to being a Luddite when it comes to preferring a paintbrush to the computer. So, when artists gained access to AI-generating tools, I wasn’t that impressed, nor alarmed. There seemed to be a lot of hoopla and fearmongering about the prospect of such a tool making art … perhaps even more efficiently than humans?

Our Nonhuman issue addresses various approaches that artists take in dealing with the nonhuman, whether it be in physical form or robotics. The Haas Brothers, interviewed by digital columnist Seth Hawkins, embrace AI-generated art and are unapologetic about it: It’s simply a tool, as they put it. So, what’s all the fuss about? Bill Smith, our creative director, ponders the future possibilities of AI, and asks the bottom line—will the collectors buy it? George Legrady talks about working with computer-generated images since the ’80s, so he isn’t so impressed with the hoopla either. On the other side of robots—and the world—Australian Patricia Piccinini’s “creatures” seem more lifelike. Contributor Barbara Morris discusses Piccinini’s hybrid sculptures of the human, animal, natural and artificial—all of which resemble living beings with hair, skin-like surfaces, eyes and mouths. The end results border on the creepy and hideous, yet a sense of a vulnerability emerges, that of an innocent child or animal. They are supernatural and hyper-real, making us wonder if this is what humans will morph into in our continuing evolution.

Or will we become puppets, wooden, void of emotion? Sophie Becker, who is featured on our cover, spoke with Publisher Alex Garner about incorporating ventriloquy in her art and taking the act on the road with her partner and dummy, Jerry Mahoney. Garner also enlightens us with a brief history of the puppets, who were presented as evil, murderous and demonically possessed. The humanlike quality of the ventriloquist’s puppet has always captured our hearts, but scared the living shit out of us too.

This issue does have a sense of doom about it, which, given the theme, was perhaps inevitable. It can be argued that the progress of Artificial Intelligence can be a good thing, right? Think of all the possible scientific breakthroughs. But robotic objects have always aroused suspicion: to be inhuman is to be immoral and uncompassionate. Can society allow AI to make our decisions for us and even tell us what good art is?

It seems to me that people will always be making art, even if they are using AI-generated art programs like Blender or Midjourney. We have a need to create, even if it’s just cooking or planting flowers. One thing this Nonhuman issue made me feel and think about—besides the overall sense of malaise—is what it is to be human, which includes holding a paint brush dipped in gooey oil paint or molding a glob of clay with your bare hands. People still need physical contact. Like Bill Smith says in his article, I don’t think we have anything to worry about … just yet.

-

From the Editor

November/December 2023; Volume 18, issue 2 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,This issue is a fave of mine. I’ve always loved crafts, especially as a youngster. I taught myself how to sew and embroider, and I made a hooked-rug wall-hanging in my high school art class. I was by far the youngest member of a quilting bee. I even considered becoming a ceramicist when I was an undergraduate. But in my mind, at the time, I didn’t think of those mediums as something to be taken seriously. No notable or major artist worked with those materials. Crafts were reserved for hobbyists—and I wanted to be an artist.

Recently, little by little, these mediums have been showing up in art galleries. Sure, Picasso and Matisse used clay as a medium, but their ceramic pieces were supplemental to their paintings. Ceramics became recognized in the contemporary fine art world with the likes of Ken Price and Betty Woodman—few other artists were working solely with the material. It really hit home when I was visiting the Frieze LA art fair last February in Santa Monica, where crafts were being prominently displayed—and purchased. There were weavings, tapestries, ceramics, embroidery, hooked rugs, you name it—about the only things missing were macramé and candle-making. Works were dangling from ceilings, covering vast wall spaces and crowding gallery cubicles, all in bright colors, messy glazes, wrinkly fabrics and unexpectedly lascivious scenarios. It was a cacophony of texture in 3D. These relatively new-to-the-art-world mediums made everything else look drab and passé.

When there’s an explosion of new art forms, one wonders if history will record it as an art movement. What caused this new attitude toward crafts, once considered the lowest of art forms found in thrift shops and beachside galleries alongside thrift-wood sculptures? Are artists rebelling against high art and the attitudes that go with it? What caused this quiet revolution in the art world?

Several theories might answer this question for our future history books. Four artists featured in our Crafts & Utility issue have different reasons for choosing their medium. Melissa Joseph, interviewed by New York contributor Annabel Keenan, uses felting to address broader social issues such as gendered labor and identity. Contributor George Melrod talks with Diedrick Brackens about his weaving works; Brackens identifies as a “weaver” and says that working in this medium is his “inheritance,” a medium that he feels has been disregarded in the art world. Sal Salandra, on the other hand, practiced needlework when he was a hairdresser, to pass time perhaps, creating flowers and cute dogs. He eventually gave up the dogs and flowers for more provocative subject matter. His beautiful new book, Iron Halo, is reviewed by Tucker Neel. Lastly, Ahree Lee’s weavings morphed from her video works and computer-related algorithms—the thinking behind both is not so dissimilar, as she tells William Moreno.

I, for one, am thrilled to see this new genre in today’s art world. The tactile freshness of these mediums feels innovative in their use and intention. It all makes me want to dust off my sewing machine—and make some art.

-

From the Editor

September/October 2023; Volume 18, issue 1

Dear Reader,

Seventeen years—that’s a long time. Most relationships don’t last that long. That number has now outlived all my other jobs; I’m referring to my relationship with Artillery. I started this magazine with my late husband in 2006, who warned me: Once you begin, you can’t go back. Boy, was he right about that. I can’t call in sick, never take a vacation or even a personal day during deadline. This is one of the most committed relationships in my life.

Even though it’s a huge responsibility, like any relationship, things can change throughout the years. Hopefully one improves with age, develops other new relationships, changes one’s look—maybe even get a facelift? (We are in Hollywood!) Well, it seemed like it was time for that makeover, and you’ve probably noticed right away that this editor’s letter looks different. Keep turning the pages (after you’ve read my letter!) and you’ll see our splendid new redesign throughout the entire magazine. Creative Director Bill Smith headed the new look and did a great job, along with designer Dave Shulman. They put in long hours in collaboration with Publisher Alex Garner and me. We’ve changed our body text, hopefully for more legibility, and added some new subtle bells and whistles. We’ve expanded our layouts to highlight more visuals—we are an art magazine, after all.

Besides the new look, we’ve added a new column, “Peer Review,” which looks at the practices of two artists. In each issue, a contributor will invite an artist whose work they admire to talk about the work of another artist, one of their peers, that they are drawn to. For this issue, Alex asked New York–based artist Fin Simonetti to participate, and she chose Ambera Wellmann, who recently had a show in Turin. Be sure to check out Simonetti’s impressive marble sculptures and stained-glass works in an upcoming show in Los Angeles this fall.

Our theme, Systems of Power, features artists whose works are politically and socially engaging, questioning and challenging the system. Can art change anything? This has been an ongoing discussion in Artillery since day one, and by now it has almost become a rhetorical question. New contributor Cat Kron talks with Martine Syms about her autobiographical films. Longtime contributor Christopher Michno writes about artists who deal with the environment, specifically climate change. East Coast reviewer Sarah Sargent gets her hands on the powerful book Redaction, co-authored by Titus Kaphar and Reginald Dwayne Betts, both of whom are prepared to take on the systemic racism in our penal system. And Bianca Collins talks with Indigenous artist Mercedes Dorame about her latest installation at the Getty Center.

We hope you’ll enjoy our September issue as we celebrate our 17th anniversary, with a new look and our stalwart regulars mixed in with new writers and reviewers. It seems hard to believe we’ve been around this long, but I guess some things never grow old.

-

From the Editor

July/August 2023; Volume 17, issue 6 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,Reading wasn’t a top priority in our family; I don’t think I was ever read to as a child. It wasn’t as if literature was banned in our house, but the walls weren’t exactly lined with bookshelves. The preschool in our tiny town was held at the local library, and that was my first real introduction to books and being read to. I loved the smells, the colorful spines and the quietness of the library. It was such a relaxing atmosphere that I couldn’t wait to visit it, and it was there that I fell in love with the world of reading.

In elementary school we had the Book Mobile (as there was only the High School Library). A van would come around the school on certain days of the month, and we could check out books. It was such a delight to walk around in its cramped quarters—and the driver was a little creepy. I looked forward to every visit with my finished book in hand, ready for another.

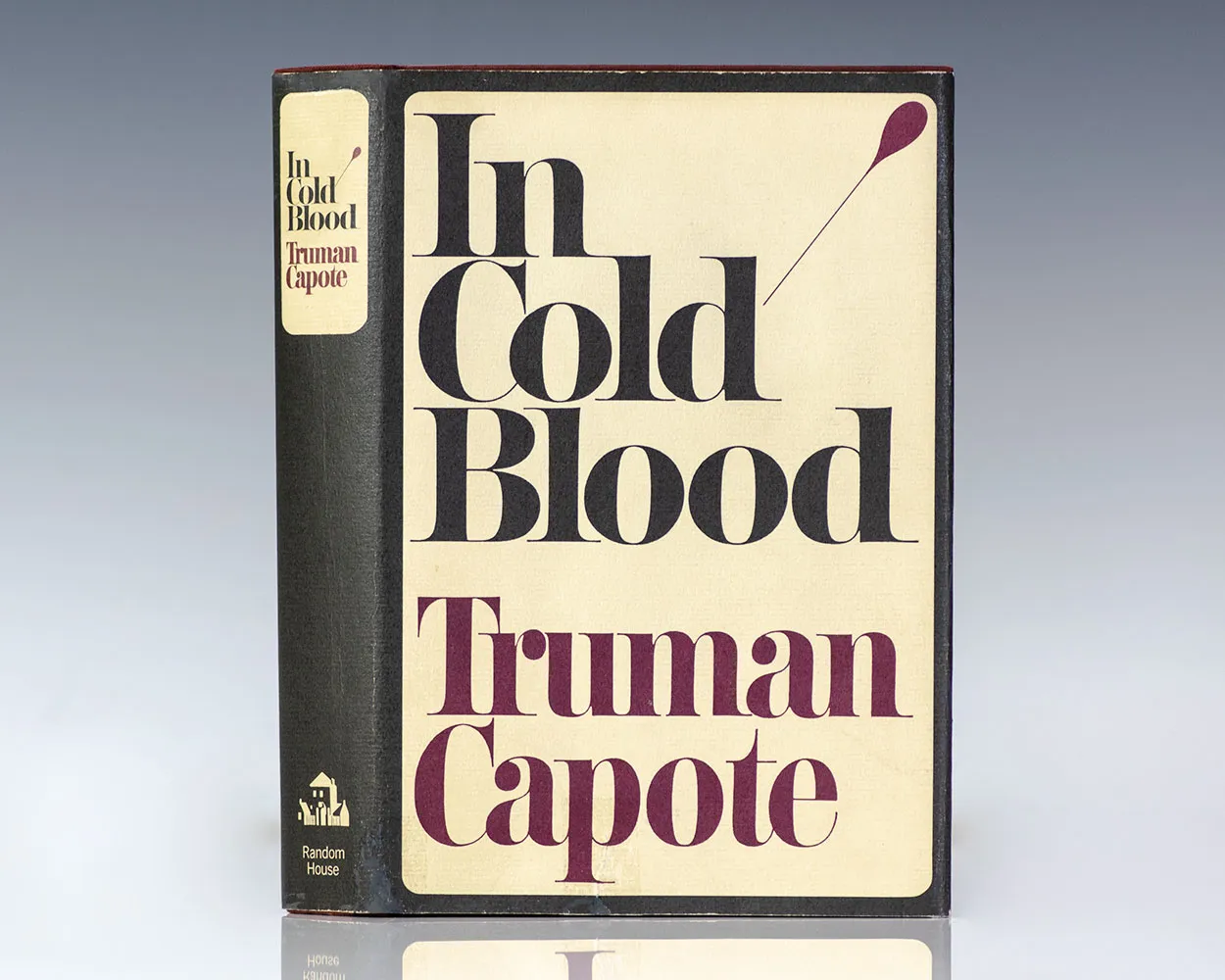

I can’t really recall what books I read, but I’m sure my selection wasn’t very sophisticated, unlike some of my childhood friends that bragged about reading the likes of Ulysses when they were nine years old. In high school my tastes began to advance. My friends were often smarter than I was, and they would recommend books. One book that I remember vividly—and which was responsible for really getting me hooked on reading—was In Cold Blood by Truman Capote. Since we didn’t live that far from Kansas, where the infamous Clutter family murder took place, the proximity added to the mystique and thrill. Every chance I got I would open that book. A few times I got in trouble for being lazy (translation: lying around reading) and was told to get off my duff, set the table, or vacuum the rug. But that book made that horrific murder come alive for me. I would be terrified and couldn’t read at night for fear it might give me nightmares.

When I left home, my first husband, an avid reader and local pot dealer, turned me on to The Beats, Philip Roth, John Cheever and Charles Bukowski—of whom I was especially fond. His work was so honest and hilariously ribald. It was inspiring to find something that I really could sink my teeth into.

As my husbands accumulated, so did my personal library. I ended up working fulltime in the cataloging department at the Tulsa University Library. I loved that job and found the two main women catalogers that I worked for to be delightfully enigmatic. I was fascinated with their job and hated to interrupt them as they were always so enrapt, sitting in their cubby holes, thumbing through the pages, taking notes. They were so smart and hip and worldly—and well-read.

I’m still a diehard fiction fan and always have a book going. I couldn’t imagine a world without reading. Every summer we publish a reading issue, just like other publications do with their recommendations. Here are ours, mainly focusing on art. We like to include films too, such as the documentary on Thomas Kinkade reviewed here by Doug Harvey. Kinkade: alcoholic misanthrope, painter of light. How irresistible is that?

No matter what your fare, we think we have an eclectic selection to consider. And don’t let anyone tell you that you’re lazy. Now get off your butt and go visit a library or buy a book—before they actually do get banned.

-

From the Editor

May/June 2023; Volume 17, issue 4 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,“Art about art is elitist,” my boyfriend in grad school used to tell me. But if that was the case we wouldn’t have AbEx, Minimalism and maybe even Conceptualism. I got it though: The art world with its various trends and movements could seem precious and pretentious. Even so, I did love painting for painting’s sake. Some would say I excelled in the non-representational art form. There’s nothing like a great abstract painting. I’d kill to own a Brice Marden.

But what about all the injustice and malaise we see today; can we really just make art that is only about art? As artists, isn’t it our duty to be addressing larger concerns? Our “Public Display” theme in this issue includes artists who consider their community and the world around them—recognizing the importance of engaging with their surroundings, they want to give something back.

Some art venues fall into the category of nonprofit organizations, which, thankfully, get the help of residents who serve on their boards and grants allotted from municipal funds. One such place is the community-building organization in Leimert Park, conceptualized by South LA’s own Mark Bradford, Art + Practice. Alexia Lewis catches up with the A+P team who run programs for teens and award several scholarships, among many other altruistic endeavors. Regular online columnist Lauren Guilford interviews Jessica Taylor Bellamy, whose work deals with LA’s unique eco-phenomenology. And our cover artist is San

Francisco–based Andy Freeberg, featured and written about by regular contributor William Moreno. Freeberg delves into the commercial aspect of the art world and exposes the machinations of that milieu—unsurprisingly it isn’t very different from any other free-enterprise world.I’ve often felt that Artillery plays a role in serving our LA arts community; at least we try like hell to. And LA gives back in buckets, especially our loyal supporters. With that in mind, I’d like to announce an important addition to our staff: our new publisher, Alex Garner. She hails from New York City where she worked at Artforum for several years, and MoMA—a little New York in our mag couldn’t hurt anyone, right? Alex knows the ins and outs of the art world and recognizes its complexities—how small it can be, yet expansive at the same time. The LA arts community is where Artillery’s heart really is and Alex is aware of the significance of our city as an art-world center, equal to New York. (Just look at all the New York galleries moving here!)

Exciting new things are in store for Artillery with Alex on board. She already has an online art column in our weekly newsletter, The Publisher’s Eye. I couldn’t be happier to begin our collaboration, putting our heads together to better serve the LA art scene. We know how important that is, and how important Artillery is to LA.

It’s hard to believe that in the 16 years I’ve run this publication (with the help of our loyal contributors and employees), things just keep getting better. Owning an art publication may seem provincial, even elitist, but I can’t help but think there’s some good that comes out of it. Art for art’s sake, anyone? We’ll take our chances.

-

From the Editor

March-April 2023; Volume 17, issue 4 Dear Reader,

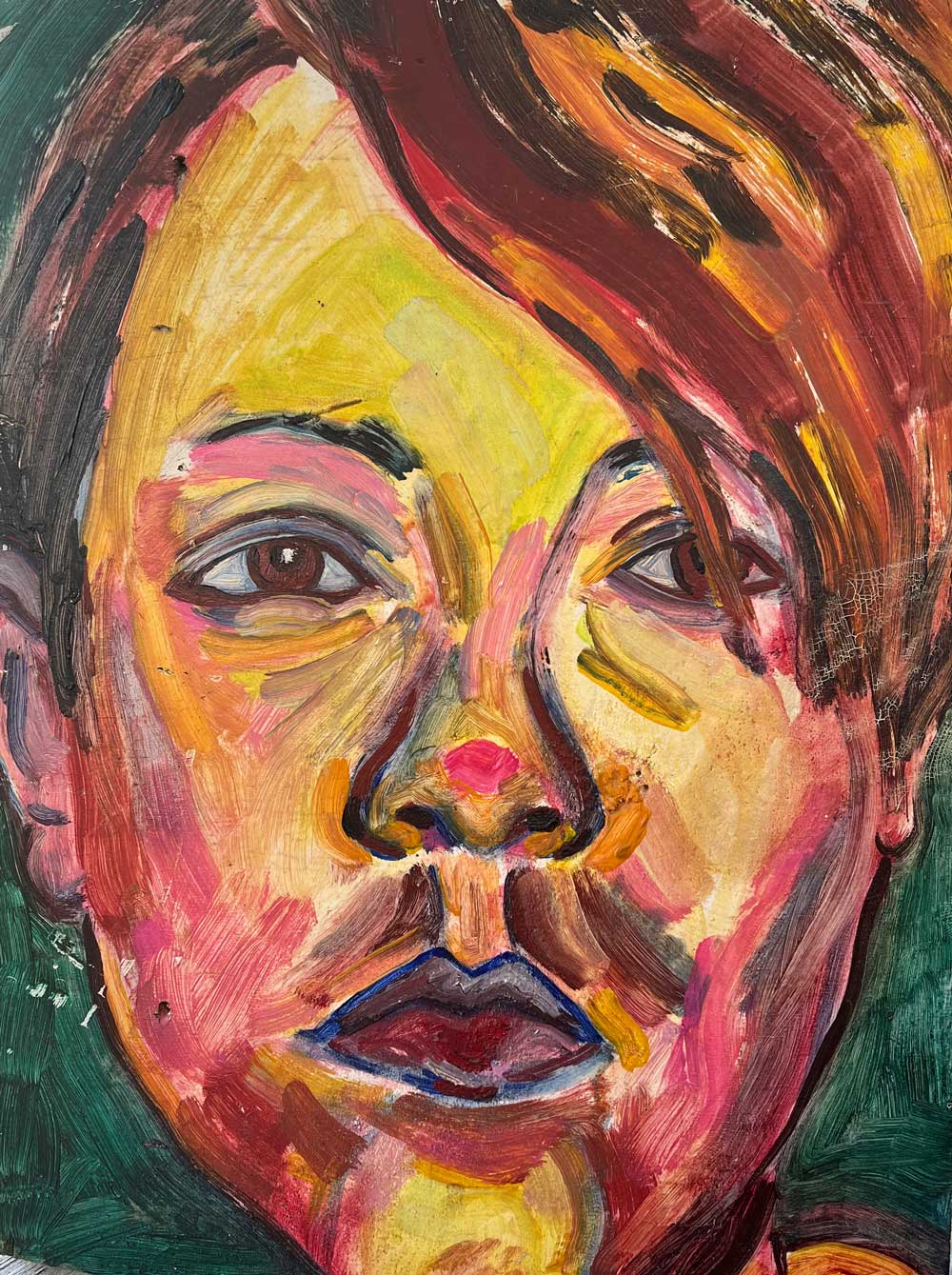

Dear Reader,As long as there are people, there will be portraits. Face it—no pun intended—people are attracted to people. We like to look at ourselves; we like to people-watch; we gaze into our lover’s eyes. Our faces are unique and fascinating: they are who we are.

As an artist, I was drawn to portraiture with my painting and photography. Once I embarked on a project to capture all of my friends’ faces (I can’t begin to tell you how many paintings that produced!). I photographed them, then painted only their faces onto an actual-size piece of found wood. Afterwards, I gave my friends their portraits—most of them tell me they still have theirs. I did this project for many reasons, but mainly to explore the mysteries of physiognomy—to discover how every face is so individual and reveals (or possibly disguises) that person’s personality.

An artist can get lost in the process of painting a face. Sometimes all it takes is the way the subject’s hair curls, a slight upturn of the smile, or the type of spectacles they wear that defines their being. Often a quick flick of the brush on a shadow or highlight is all that’s needed. Something so minute might be the ticket, then it’s done.

Each artist we feature here has their own unique approach to portraiture. Amir H. Fallah’s paintings involve complex narratives that address cultural boundaries. In his current body of work most of the faces are covered. Fallah’s elaborate figurative paintings are not drawn from actual people he knows, but from imagery found on the internet.

On our cover is Helen Chung’s painting of LA artist Senon Willams. Writer/critic Ezrha Jean Black sits down with Chung to discuss anatomy and the intimacy involved with the act of painting the sitter—which is Chung’s preferred method.

Luis Sahagun’s portraits employ traditional Meso-American healing rituals. His role as the artist is that of a spiritual consultant who examines the person he may doing a portrait of and what their ailments might be, often the result of social stresses. Sahagun will then apply the necessary materials that reflect the broken parts of that person’s being. In one instance, he does a self-portrait of when he experienced racism at college. David S. Rubin interviews the Mexican-American Chicago-based artist.

Henry Taylor is a storyteller with his portraits, written by Donnell Alexander. But don’t call him a portraitist. That was stressed in the opening press preview. That could also be said of many artists who are known for their portraits. Though don’t all portraits tell a story? Once you put a face on it, you’ve got a story—a person, a life.

If one visits the art galleries these days one does find that there’s an uptick in portraiture. Maybe that’s a sign that we are still human, and in these days of AI, that’s something to hold onto dearly.

-

From the Editor

January-February, 2023; Volume 17, issue 3 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,My social media intern recently sent me a text with an unmistakable degree of urgency. She stated that Chance the Rapper was trying to get in touch with me by Instagram message. “Who?” I replied. My assistant, being of the millennial generation, was not at all surprised by my ignorance. I think she even anticipated my dumbfounded reaction, hence her urgency. “I don’t think you understand,” she said, and proceeded to explain the relevance of the young rapper and how remarkable it was for him to actually be reaching out to us on our Artillery Instagram—let alone that he is a follower. Of course, an introduction was immediately made.

What on earth would a noteworthy musician such as Chance want with me, an editor of an art magazine? My interest was piqued. After informing a few of my younger friends, it was confirmed: It was extraordinary that this massively popular rapper was reaching out to me.

My assistant made the e-intro and soon we were united, digitally; there was to be a Zoom meeting. I included my assistant in the thread and the Chance team joined in on the Zoom call, about six of us in all. A few faces made an appearance, but most of the participants kept their video off. We were all waiting for Chance. I was nervous by now, and still couldn’t imagine what this meeting was all about. Soon he appeared, but not in the flesh (as it were). There was a big letter C that pulsated in rhythm to his speaking voice, like the all-powerful Oz, although Chance was soft-spoken, thoughtful and polite.

I was informed that Chance has been collaborating with the fine-art world on a specific art project. He was working with the Black Diaspora and wanted more inclusion of these important artists. Being from Chicago, and a regular patron of the arts, Chance couldn’t help but notice the lack of Black artists in the art world and the elitism that exists in the fine-art world. Unfortunately, I found his observations to be quite accurate.

Chance would be in LA in September, doing another collaboration with artist Mia Lee (whose portrait of Chance is on our cover), at the Museum of Contemporary Art. I contacted writer and hip-hop aficionado Donnell Alexander—who I’ve known for years, since the old LA Weekly days—and he was eager to do something on Chance, for whom he has great respect.

Chance is very keen on working with African artists and this project will end up in West Africa in the New Year. It so happened that a new gallery in West Hollywood, dedicated to exhibiting African artists, caught the eye of writer Donasia Tillery, who appears in the issue with a Zoom interview of African art dealer Adenrele Sonariwo from Lagos. Annabel Keenan, our New York contributor, writes about New York–based Trinidadian-American Allana Clarke’s work, which deals with Black attitudes to hairstyle. All this came together to present features on the Black Diaspora Emerging in the art world.

I love starting off the New Year with fresh new content and a rapper on the cover. It’s nice to mix things up a bit. Isn’t that what art is supposed to be all about? The art world is constantly changing, just keeping up with the world. And Artillery is right there with it. Happy New Year art lovers!

-

From the Editor

November-December, 2022; Volume 17, issue 2 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,This Women’s issue is not our first, but we welcome any opportunity to celebrate women artists, curators and dealers. Normally our November/December issue is our Interview issue, but in light of the recent overturn of Roe v. Wade, we made the decision to exclusively profile and interview women in the arts. As with all our themed issues—our unique Artillery modus operandi—I personally worry about who we might have left out. (Ah, the stress of being an editor.) So, bear in mind, we simply cannot cover every worthy female artist, but this time around we wanted to champion the particular women featured in this issue.

One woman who did not make it into this issue that I would like to personally celebrate and acknowledge is Diane Arbus. I was recently in New York and had the opportunity to see the rare showing of all of Arbus’ original photographs from her famous Aperture book and MoMA 1972 retrospective at the David Zwirner Gallery in Chelsea. We’ve all seen the photos in the book, and a smattering of those images in museums, but the complete series hung with deft curation was a sight to behold. I thought of this artist—a privileged white woman, for sure—going around the streets of Manhattan in the 1960s with her Rolleiflex camera in hand, asking passersby if she could take their photograph. Her confidence and unabashed behavior must be applauded. In a way she was rebelling against her wealthy upbringing by turning the spotlight on people that were not part of her world. Some might call it exploitation, but I hardly see it that way at all.

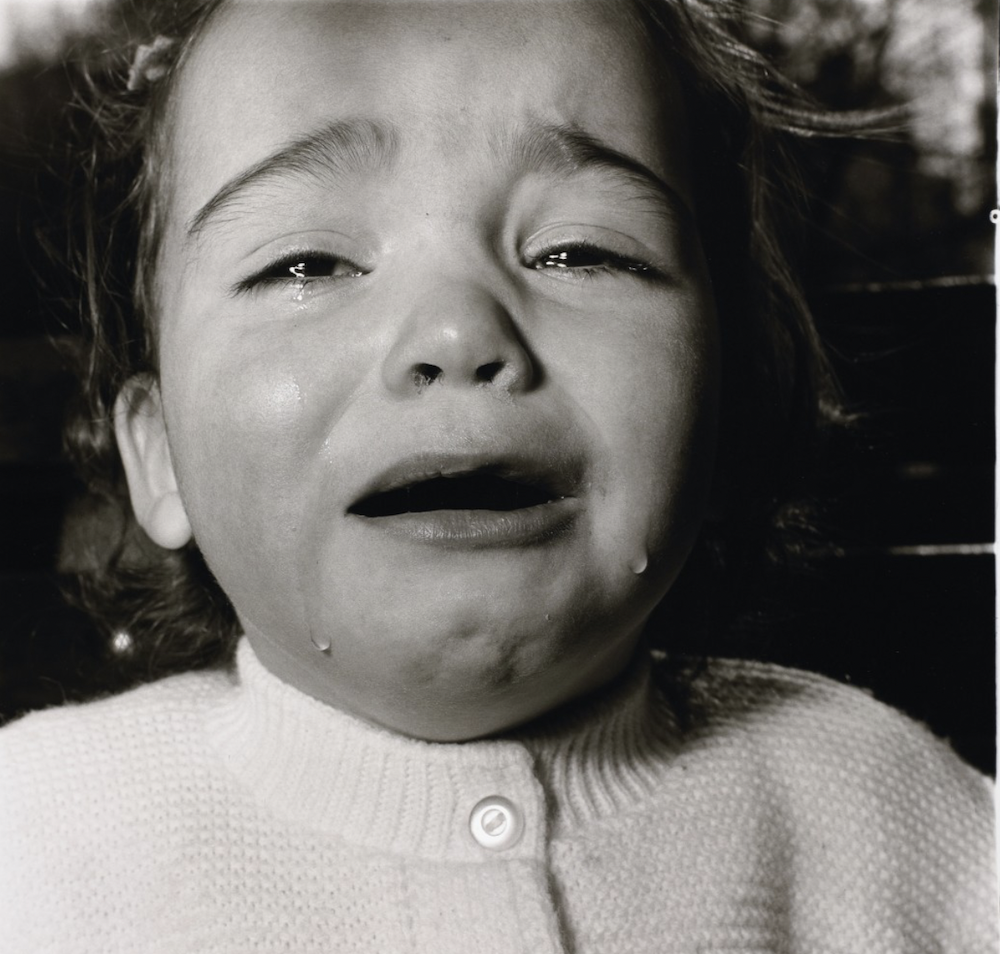

She was an inspiration to me as an artist, as I’m sure she still is for many women artists. One thing I always remember, from the excellent biography by Patricia Bosworth, was how Arbus told her students to go out and take a picture of what they most feared. As a teacher I followed her lead, and as an artist myself I listened to this daring but sage advice. By receiving trust from the people she photographed, she bared her own soul in those images. How in the world did she manage to get invited to the giant’s home to take a family portrait? How did she get those twins to confront the camera, motionless? How did she get that perfect moment of an infant with tears streaming down her face?

There will only be one Diane Arbus. She was a trailblazer with a message. Isn’t that what art is all about? Many of the artists we feature in this issue follow their heart just as Arbus did. Michele Pred works with women’s issues such as abortion rights; Calida Rawles studies the complexity of being a Black woman; Astra

Huimeng Wang explores the Western world’s fictions from the perspective of her native China; and Kristin Bedford photographs the subculture of Latina women and lowriders with as much empathy and compassion as

Arbus brought to the streets of New York. Her cover photo aptly exemplifies this and speaks to a world full of women with a most important message. The Latina’s tattoo No Soy De Ti, translates to “I Don’t Belong To You.” I think that says it all. -

From the Editor

September-October, 2022; Volume 17, issue 1 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,As I’ve been saying since the dawn of Artillery (16 years ago now): LA is the most vibrant art city in the country. This isn’t exactly a revelation, so why focus on LA—yet again—in this current issue? Because we felt it was worth revisiting the subject in order to help all the high-end international and New York galleries that are moving here to settle in and feel secure that they did the right thing.

I made a point to get out more this summer and was reminded how exciting LA’s art scene really is. Our recent transplants might be happy to know that we celebrate summer in a big way, with glamorous alfresco galas held in spacious plazas on balmy nights. This season, my art expeditions took me to The Cheech gala benefit in Riverside, a surprisingly quaint and dusty city about an hour’s drive from LA, while Night Gallery held their Sexy Beast Benefit Auction for Planned Parenthood at their newly expanded space. A stage was set up in the spacious outdoor area for the emcee and various comedians; local vendors served duck tacos and vegan croquets, and there was plenty of wine. Both events—filled with mirth (and hopefully deep pockets)—were for worthy causes.

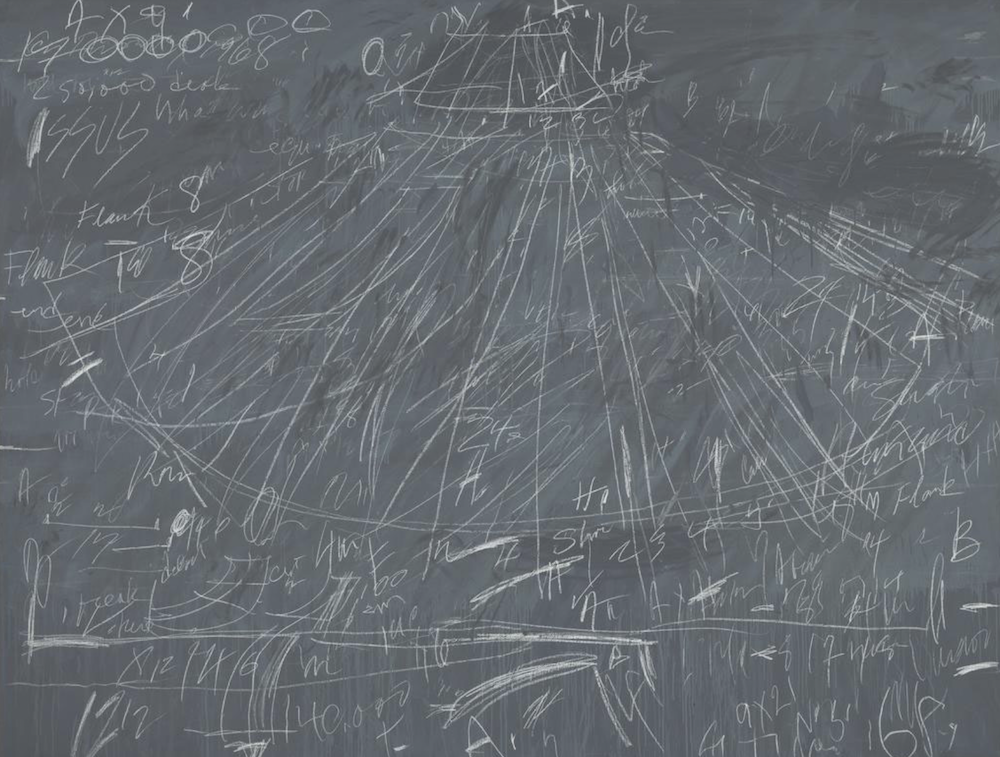

A Cy Twombly exhibition found us at an early evening preview and reception amid the marble and fountains on the Getty Plaza as we sipped wine and watched the sun set over the Pacific. Then there’s always The Hammer. Everyone loves the Hammer openings (sometimes affectionately known as “the Hammered”). The opening celebration was for Andrea Bower’s powerful survey exhibition, which felt eerily prescient and poignant considering that Roe v Wade had just been overturned. However, we were a bit nonplussed by the scene of caterers whisking away the VIP spread promptly at 8 pm when the hoi polloi arrived. Uh, let them eat breadsticks?

Galas and benefits aren’t the only show in town, of course. There are still tons of gallery openings to go to—and drive to, unfortunately. Getting to and from all these events is a huge inconvenience in such a sprawling city. Attending a Getty event means leaving a few hours early, and begrudgingly having to stay sober for the drive back. Going from opening to opening can be a drag—parking counting for most of the discontent. There can be a lot of ground to cover if you want to fit in several openings—and this is the biggest drawback to living in this great metropolis.

I’m sure the new kids on the block aren’t strangers to big cities though, and we’re only too happy to show them around. Our cover artist, Zoe Walsh is interviewed by newcomer Olivia Fishman. Their complex stunning pool painting series seemed apt for a typically sweltering LA September. Contributor Clayton Campbell profiles stalwart local artist Mark Steven Greenfield, whose work continues the much-needed dialog surrounding racial tension. Doug Harvey steps in with a piece on desert artist Daniel Hawkins—his light tower installation is having its fifth-year anniversary. And there’s much more: Ask Babs confronts Larry Clark; our comic-strip duo knock it out of the park with their spoof on LA architecture, plus reviews of summer shows.

So, if you’re new in town, get out there and see LA’s best for the beginning of the art season (check out our Fall Previews). And if you’re not new in town, get out there anyway. Happy Fall Art Season Art Lovers! Aren’t you glad you live in LA?

-

From the Editor

July-August, 2022; Volume 16, issue 6 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,My late husband was a historical biographer with four published books; three of them were written during our marriage. It was an eye-opener to live with someone who writes for a living. For one thing, it seemed like he did a lot of nothing. He would

oftentimes just sit on our deck and read all day, and he spent hours on end in libraries. While I toiled away, chained to my computer, chasing writers, responding to endless emails, there was my husband, just sitting in our black leather chair—reading! “What are you doing today?” I would ask, and he would always remind me: “I’m working, honey….”Taking time out of one’s day to read does feel like a luxury. Our Protestant work ethic frowns on such an activity. But what about someone like LA artist Tim Youd? He reads books, then rereads them while retyping them for his art? I think I’d have a fit if I was his wife!

One of Youd’s “finished novels” appears on the cover of our Summer Reading issue. In April, I flew out to Nebraska to visit Tim and watch him perform in Red Cloud, retyping The Song of the Lark, by Willa Cather. Having close contact with him, the Willa Cather Center staff—and most of all, The Prairie—made the experience of reading Cather incomparable. If I had access to the location and surroundings of every novel I read, my reading pleasure would be that much more meaningful. Tim’s performances, which took me to the various spots of Cather’s upbringing, elicited a deeper comprehension of the author and her story. Youd impresses upon his audience what it might feel like to spend one’s entire day with a book. He starts every morning fresh for a new day of reading. The only time I feel like I can do that is when I’m on vacation.

I invite you to read (when you have the time) about Youd’s 100 pilgrimages to authors’ haunts as he retypes their novels and how he came to start this unique and formidable project. Please take a gander at other worthy items in this issue. Writer/artist John Tottenham treats us to his tribulations in the publishing industry. There are some big laughs to be had in his essay, which will continue as a featured online series, keeping us abreast of his efforts to get his novel into print. The books we are reviewing also make for richly rewarding summer reading: Brave New World: The Graphic Novel, reviewed by Glenn Harcourt, reminds us how prescient Aldous Huxley was and demands a must-re-read (with pictures this time around). Another good read about the late great LA guru conceptual artist Chris Burden is out now: Poetic Practical. All of Burden’s unrealized projects are in this book, attesting to how he was always ahead of his time.

So, this summer, take a book on your plane flight; bring along a copy for your camping trip; lug a novel to lounge by the pool. Whatever it takes, read a book. No matter what time of day.

-

From the Editor

May-June, 2022; Volume 16, issue 5 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,This issue is about art being made outside of Los Angeles and New York. If art is being made and shown at reputable galleries in those cities, it has the stamp of approval: Collectors can feel safe that their taste is superb and their investments are secure, and even more importantly, they can always flip the art and make loads of money.

I had a different approach to my editor’s letter before a PR email arrived from David Kordansky Gallery, a prominent LA gallery that recently added a space in New York. It’s one that I admire (even though they don’t advertise), with many good artists on their roster. The artist they were promoting at the Frieze New York art fair was Mai-Thu Perret. The image included was of a very large ceramic flower with a phallic emphasis. It caught my eye, not only because it was a gorgeous piece to behold, but because it also bore a distinct resemblance to a ceramic piece featured in this issue by Kansas City-based ceramic artist Linda Lighton (see page 37 and whose work also graces our cover). There’s certainly nothing wrong or unflattering about that.

Sometimes I will see a notable artist’s work here in LA, and it will remind me of another artist that works in the hinterlands. I will forward the image, telling them that they must be doing something right. This is the very reason I chose to expose what artists are doing outside of the major metropolitan art centers for our Beyond LA issue—because for purely geographical reasons their work often doesn’t receive the exposure it deserves.

When a friend and colleague, writer Frances Colpitt, reached out to ask me if I’d be interested in her writing about a Texan artist whose early career she’d been following, I was game, because anything Frances writes is gold to me. But then I got to thinking, why not do a whole issue on artists that work outside the big cities: We’re all thinking globally now, why can’t that include middle America?

Is the art being made in cosmopolitan centers better because it’s being represented by high-end galleries? We live in a hypercapitalist society where the rich just get richer and the poor stay poor. It’s quite simple really: rich people need things to buy with all their money.

So I wanted to take this opportunity to expose some hard-working artists living in all parts of the US. We’ve got artists from Fort Worth, Chicago, Kansas City, Richmond, Virginia and Lincoln, Nebraska. I was knocked out by all of them. Of course their art is just as valid as Mai-Thu Perret’s. It’s just not being shown at David Kordansky Gallery.

-

From the Editor

November-December, 2021; Volume 16, issue 2 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,I had the unexpected pleasure of spending four hours at Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum with my 93-year-old mother-in-law recently. Not that visiting the Fogg is unusual—we’ve done it for years, practically every summer. But this time we spent four hours looking at art!

As we sat in the café area, realizing we wouldn’t be enjoying our planned leisurely lunch—a COVID casualty—my mother-in-law stabbed her cane into the floor as she creaked up out of her chair, signaling let’s get started. One of the first paintings we lingered over was a Kerry James Marshall self-portrait of the artist holding a paint brush and jumbo-sized palette in the foreground. I leaned over to tell my mother-in-law a little about the artist and his importance in the art world. She listened intently, then responded, “Hmm.” We then walked away in different directions, on to the next piece—being mindful to give one another our own time with each work. I noticed how my mother-in-law stayed with every piece, much longer than most museumgoers (who apparently spend an average of three seconds with each painting). She would read the placard, study the piece, then refer to the placard again. If something was of particular interest, she would come over to me and comment on what she had just learned. We would then look at the piece together, with me often elaborating upon it.

We wandered through the museum’s impressive permanent collection, starting with Modernism, ending with contemporary art. We oohed and aahed at the Pollock, wondering if it was incorrectly hung, as it was atypically vertical. When we got to a Louise Nevelson, my mother-in-law was blown away by the large black wall sculpture—she was not familiar with Nevelson’s work. We sat in silence on a bench positioned directly in front of the entire piece. I wondered aloud if all of the black painted wooden shapes were found items. I walked toward the placard and announced that indeed they were. We started pointing out each form that we found particularly interesting or discovering something so obvious, like a leg of a chair. I related how Nevelson, one of the few women sculptors of her time, once stood up at a sculpture conference and proclaimed “I have balls too!” My mother-in-law smirked a little at that story.

We were approaching a curtained-off room at the end of the exhibition where a film was screening, and I asked ma-in-law if she wanted to watch it. We both liked the idea of sitting in a darkened room and resting our weary feet. The short film—Phat Free by David Hammons—was shot with a hand-held camera as it followed Hammons kicking a bucket down the streets of New York City at night. The only sound was the clanging of the bucket rolling on the pavement with peripheral city noises. We sat in silence; mesmerized.

When we got home, we both knew we had experienced something very special together. She told me how she appreciated going with me as my stories added so much more to the experience.

We hope this interview issue will do the same, provide a deeper understanding of how an artist works, how a gallery operates, and how one’s background determines one’s career choices. More knowledge of something is always a good thing, just ask my mother-in-law.

-

From the Editor

September-October, 2021; Volume 16, issue 1 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,Happy Birthday to Artillery for turning 15 this year! And to celebrate this milestone we are covering how the world is going to hell!

The climate crisis is our September theme and it wasn’t an impromptu decision or stop-the-presses situation because of the recent U.N. announcement stating our planet is in dire straits. A climate issue had been lined up for quite some time; we just didn’t realize it would be at critical mass when we got around to doing it.

It seemed like every artist we knew was doing something about the environment. Why hasn’t the rest of the world caught on? Even I, at the tender age of 16 in my high school biology class, made a pledge to never litter—and I really don’t care to mention how long ago that was!

Point being, artists have been doing their job. Does it help, does it matter, does anyone really care? Reading the articles in this issue, I would say that it does—and perhaps some reconciliation between art and politics can bring forth some change by exposing this work to our readership; or at the very least some much-needed immediate action.

Artists in general are very sensitive types, or at least in the beginning, before they become art stars. So it wasn’t hard to come up with an incredible roster of (youngish) artists who are putting forth their efforts into saving our planet. Let’s start with our cover artist, Brooklyn-based Zaria Forman, covered by New York contributor Annabel Keenan. Upon Forman’s first trip to Greenland, she discovered how the changes in the ice fjords were affecting the locals, and made a commitment to tracking the adverse changes in our climate. She traveled to Antarctica and Arctic Canada to record the transformation in ice. Her drawings of icebergs and glaciers are formidable in size and detail. She uses soft pastels to achieve the amazing realism with these images. Please take a look at her breathtaking drawings inside these pages.

Regular contributor Leanna Robinson addresses the issue of water with her coverage of Los Angeles artists that call attention to our misuse and exploitation of water, to the point of contamination and causing our fresh-water creatures to die off due to the unnecessary damming of rivers that pump water into places that just don’t have water, and probably shouldn’t.

Is all this starting to sound like a futuristic horror movie? Look no further than the pages of Lauren Guilford and Geena Brown, where they turned to artists Max Hooper Schneider, Hugh Hayden and Kiyan Williams for their takes on the impending apocalypse. Nothing scary about that.

Finally, we get a very realistically dismal picture that articulates the state of the world and how we reached this point: the big C—Capitalism. British writer Eli Ståhl interviews renowned climate expert T.J. Demos whose new book Beyond the World’s End: Arts of Living at the Crossing further explains the connections between capitalism and our planet’s impending demise, and how art can be used as a tool against it.

After all that, it’s hard to think about Artillery’s 15th anniversary, and that all my efforts to not litter didn’t really seem to pay off. I will persevere though and hope you will too. We all have to take it up a notch and do our part. I hope this issue at least gets that message across.

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,