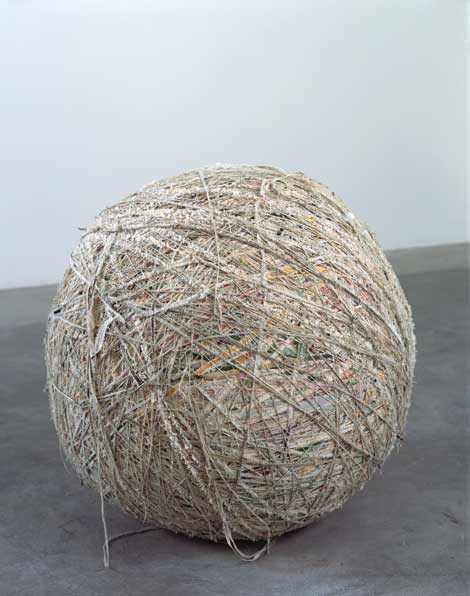

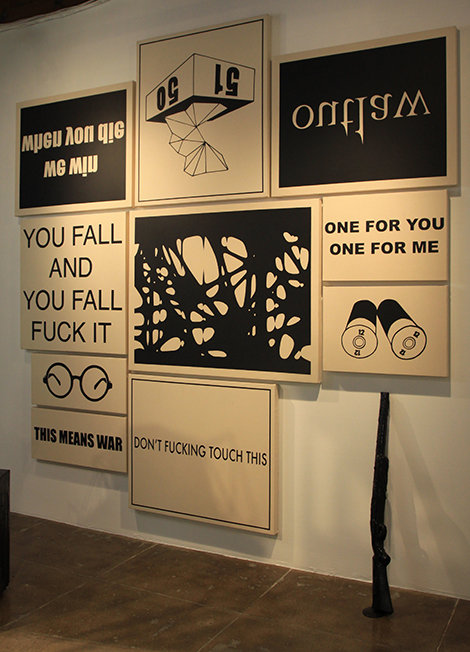

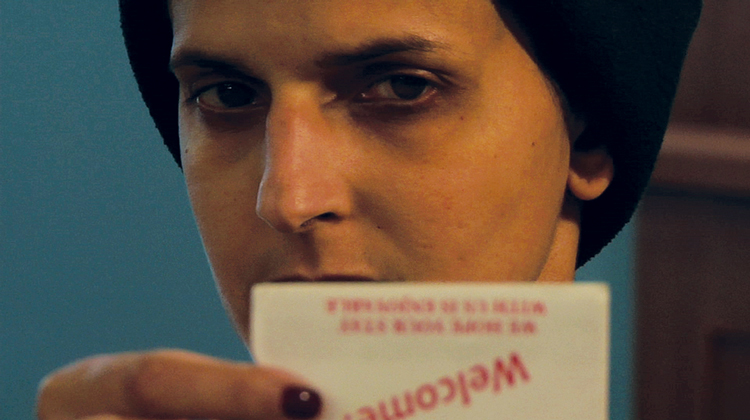

If you are one of the cool kids (or artists or gallerists), then most likely you were at 3rd street in DTLA last Saturday for a jam-packed and super festive opening. We aren’t talking Hauser, rather its newish next-door neighbor Over the Influence. OTI—with its Hong...