Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Patricia Lea Watts

-

59th International Venice Biennale

Milk of DreamsFiguratively speaking, this year’s Venice Biennale is a “Brick House;” a metaphor for what creative women are capable of achieving when given the opportunity. Cecilia Alemani, the first Italian female curator since the inaugural Biennale in 1895, has included a majority of works by women and gender-nonconforming artists. Gratzie! “Milk of Dreams,” a provocation borrowed from the book by surrealist painter Leonora Carrington, symbolizes the role imagination can play in addressing humanity’s fate. The first Black woman to represent the US Pavilion, Simone Leigh, from Chicago, wins the top Biennale prize for her imposing bronze sculpture, Brick House. A female head sits atop a wide-skirted Mousgoum dwelling design; at 16-feet-high, the powerhouse archetype speaks to the Strong Black Woman schema.

Colonial oppression and its impacts on Blacks and Indigenous peoples has a violent cultural and ecological legacy. In response, the Nordic Pavilion became The Sámi Pavilion, featuring work by Indigenous artists. Standing across from the closed Russia Pavilion in the Giardini, with Italian Polizia standing guard, Sámi artist Máret Ánne Sara hung sculptures of pendulous preserved reindeer calves inside dried tundra plants, and dried inflated stomachs suspended by sinew; an extreme aesthetic for the art world, perhaps, though the Sápmi region covers the far northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. Adjacent is a multi-panel mural by Anders Sunna that narrates his family’s decades-long struggle to maintain their status as forest reindeer herders. Choreographed performances at the opening in April, titled Matriarchy, by theatre director and Sámi land guardian Paulina Feodorff, involved a promenade of silent characters miming the need for listening to non-humans. Seated on tree stumps, visitors wearing headphones watched a two-channel video and listened to Sámi Elders speak of having their lands taken away, similar to the Indigenous Peoples of Turtle Island. The Sámi’s way of life, centered on their relationship with reindeer, is severely threatened because of colonial extractivism and climate change. This melancholic nature-based installation seeks to illustrate an eco-consciousness, to communicate Sámi traditional knowledge.

Turba Tol Hol-Hol Tol at the Chile Pavilion, Arsenale, Venice, Italy. Photo by Patricia Watts To enter the Chile Pavilion at the Arsenale can take a while; the immersive multimedia installation Turba Tol Hol-Hol Tol, can allow only a few people every 15 minutes. Envisioned by curator Camila Marambio as a collaborative project including artists, scientists and traditional knowledge, the title translates as “heart of the peatlands” in the language of the Indigenous Selk’nam people of Toerra del Fuego. Pavilion attendants share fragrance samples of peat moss (Sphagnum) with visitors, while waiting in line. A Selk’nam guide, completely silent, leads visitors up a ramp, over an experimental growing field, and into a circular multimedia platform. The room darkens and vivid projections appear as participants drop deep, virtually, down into a bog. Not exactly VR, though the sound effects create a sensation of falling inside the earth. The guide then returns the group back down the ramp where we learn how growing peat in labs can avoid the destruction of natural peatlands used for fuel and growing food. In response to the climate crisis, the installation presents an intriguing path forward. Peatlands are a highly efficient carbon sink and extremely vulnerable; conservation is imperative. An immersive installation with a provocative proposition, though no artist is officially named—the focus is exclusively on Peat.

Additional pavilions not to be missed in the Giardini include Brazil, where Alagoan artist Jonathas de Andrade has you enter his sensorial installation through a large sculptural ear, à la science fair. Titled With the Heart Coming Out of the Mouth, the human body is experienced in parts as emotionally charged terrain. At the Poland Pavilion, Re-enchanting the World by Roma artist Malgorzata Mirga-Tas, a luscious 360-degree floor-to-ceiling textile mural or “picture place,” captures the rich culture of itinerate life. A collateral exhibition, Ocean! What if no change is your desperate mission? by South African artist Dineo Seshee Bopape, includes a three-channel video and sound installation of moving water taken in the Solomon Islands, a mediation with clapping sounds presented at the dramatic Iglesia di San Lorenzo. One outlier, not officially included in the Biennale, is Planet B: Climate Change & the New Sublime at Palazzo Bollani, an exhibition in three acts developed by French curatorial cooperative, Radicants, including Nicolas Bourriaud. They propose that our relationship with Earth is transforming through the horrors of extreme climate events, and that the artist’s gaze, the sublime, has been altered. Fortunately, there appears to be an eco-consciousness and some simple solutions to engage with at the 59th edition of the Venice Biennale.

-

Pitzer College Art Galleries; Elephant: : Cathy Akers

For over a decade, Los Angeles artist Cathy Akers has tenaciously researched two experimental open land communes in Northern California—Morningstar and Wheeler’s Ranches, each historically located in West Sonoma County. Through the years the artist has built relationships with former commune residents, collecting stories about both their utopian aspirations as well as the dysfunctional implications of these back-to-the-land communities. Akers animates archival photographs and interview texts to create her melancholic yet playful ceramic and photographic installations.

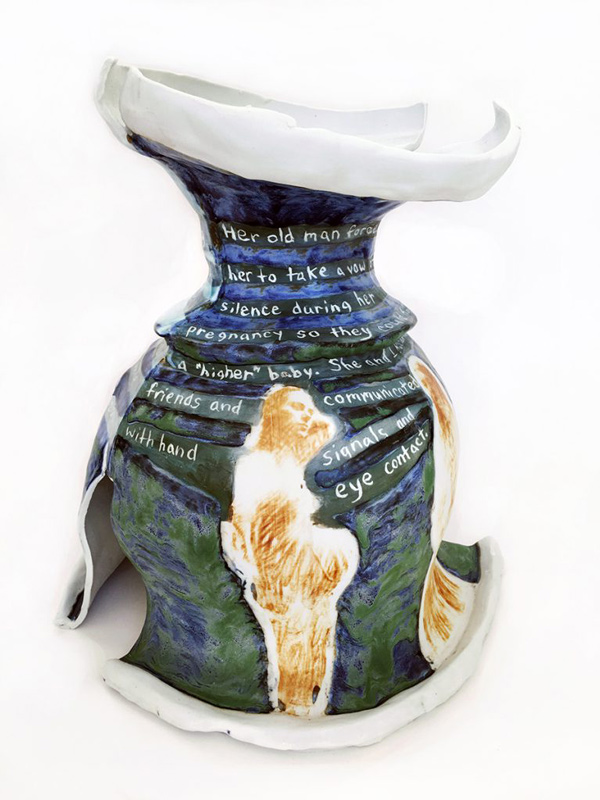

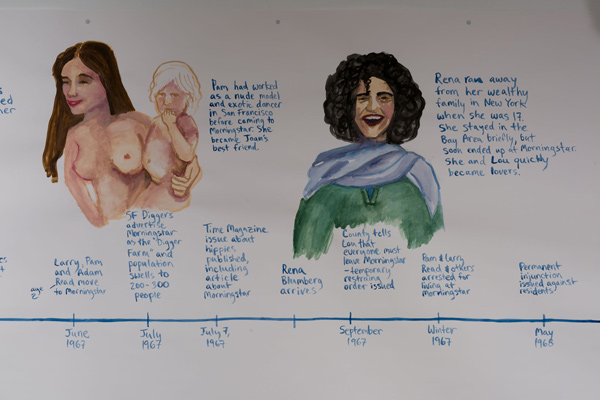

Cathy Akers, “A Utopia for Some: Morningstar and Wheeler’s Ranches Reconsidered,” Pitzer College Art Galleries, installation view. A Utopia for Some: Morningstar and Wheeler’s Ranches Reconsidered at Pitzer College is the largest of two shows Akers has up through March. The main wall displays hand-painted timelines for both communes, including portraits of key figures, starting with Lou Gottlieb in 1965, owner of Morningstar. Depicted are noteworthy events such as Time Magazine’s July 7, 1967 issue, The Hippies: Philosophy of A Subculture, which included a feature on Morningstar. Also mentioned was the 1969 Halloween FBI raid at Wheeler’s Ranch during which founder Bill Wheeler was arrested. A grouping of small claymation-like fired ceramic nude figures populates wood stumps, with one figure playing guitar and the others happily communing with children and dogs. Archival photographic stills from the communes play on a video loop in an adjacent darkened room. Large glazed ceramic vessels with photocopy transfers of commune residents and sgraffito quotes lie seemingly broken, perched on cut tree logs.

“Since we didn’t have TV or go to school, we had to find ways to entertain ourselves. Any drug that was available I was willing to try. Anytime we got a hit of acid or two, we would split it up. The big kids could have half a hit and the little kids could only have a quarter hit.”

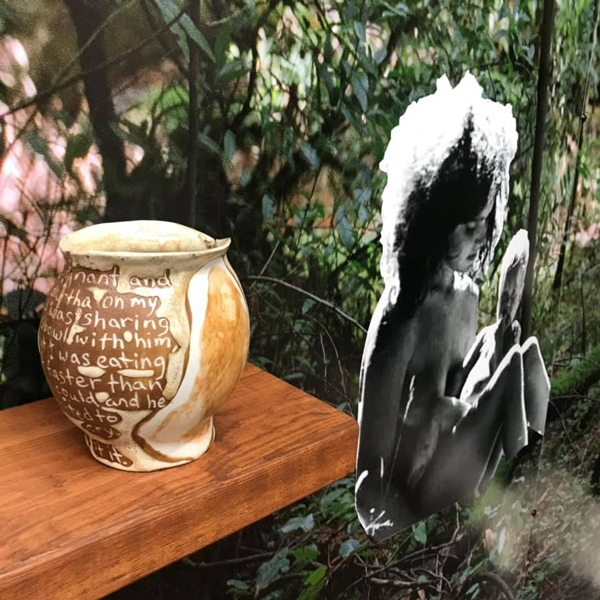

Cathy Akers, “Stories from the Revolution,” Elephant, installation view. Cathy Akers: Stories from the Revolution at Elephant in Glassell Park, also up through March, is a small room with three full-wall photo murals and ceramic vessels resting on wall shelves. In the corner, one large vessel sits precariously placed on a vertical log. This smaller immersive space offers a vicarious moment placed in the land—a clothing-optional existence and pilgrimage site for the Diggers who traveled back and forth between Haight-Ashbury and either Sebastopol and Bodega during the Hippie Revolution.

Cathy Akers, Expectant (2018). Porcelain, photocopy transfer, underglaze, glaze. Akers, who was born in 1973, the year both communes were shut down, sets out to examine aspects of human nature that desire an ideal society. In the course of her research she has found that the women and children who lived this voluntary primitivism also endured physical and emotional hardships that were often downplayed in the name of freedom. In a zine created by Akers, Bill Wheeler tells a story about a short-term commune resident known as “Oak Grove David” who created a group on his land where women were completely dominated and “slept with men on a rotating basis.” Wheeler also revealed that David’s “followers were encouraged to sever ties with old friends and relatives.”

With these two shows Akers’ perspective on hippie culture evolves alongside of her development with narrative forms in ceramics and photography. She delivers her message with a raw but knowing home grown aesthetic.

Cathy Akers, “A Utopia for Some: Morningstar and Wheeler’s Ranches Reconsidered,” Pitzer College Art Galleries, installation view. A high quality 40-page Utopia for Some zine is available for free at both locations.

Cathy Akers, “A Utopia for Some: Morningstar and Wheeler’s Ranches Reconsidered,” February 2 – March 28, 2019, at Pitzer College Art Galleries, 1050 N. Mills Avenue, Claremont, CA 91711. www.pitzer.edu/galleries

Feminisms, Motherhood, and the Counterculture, a panel discussion with Cathy Akers, Micol Hebron, Olga Koumoundouros, Claudia Parducci and Astri Swendsrud, at Pitzer College Broad Performance Space, Wednesday, March 27, 2019, at 1:30 PM.

Cathy Akers, “Stories from the Revolution,” March 9 – 30, 2019, at Elephant, 3325 Division Street, Los Angeles, CA 90065. elephantartspace.blogspot.com

-

Joan Jonas: Moving Off the Land

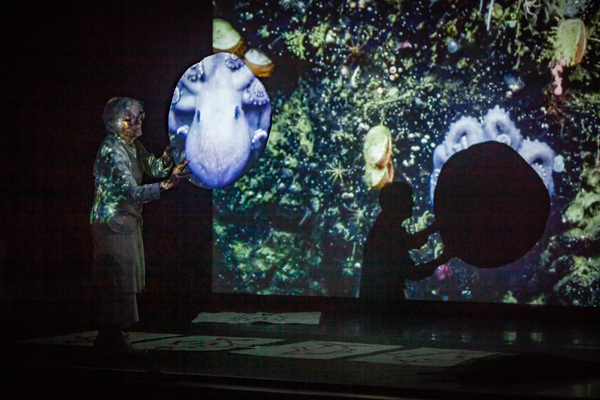

To coincide with this year’s fourth edition of the FOG Design+Art Fair, the Fort Mason Center for Arts and Culture invited pioneering multimedia artist Joan Jonas to present two live performances at the center’s Cowell Theater. In the work, titled Moving Off the Land, Jonas gave a fact-based art/science lecture as performance, integrating her signature live drawings and interactions with video projections, with an urgent focus on impending fish extinction and our ancestral relationship with oceans.

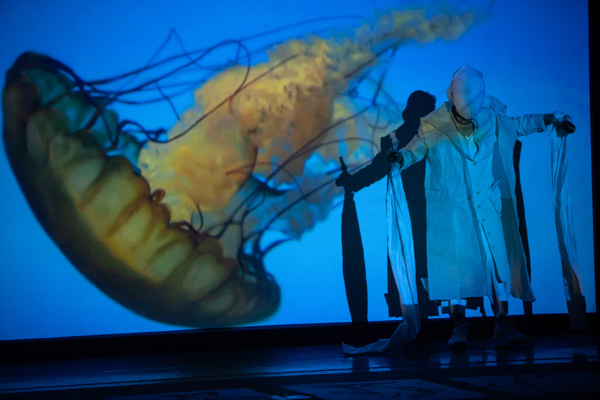

Joan Jonas, Moving Off the Land, January 19, 2019, at Cowell Theater, Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture. Photo Credit: Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture/Justine Oliphant Jonas has focused on nature and the landscape in her videos and performances since 1968, when she made her first work filmed outdoors, titled Wind. Through the years she has presented highly conceptualized engagements—works to be, in her own words, experienced, not understood. Moving Off the Land, which was commissioned by TBA21-Academy, an itinerant cultural producer focused on ecological issues, represents a departure for Jonas. “This is my first collaborative work with a scientist,” the artist said in an interview before the performance. “I taught at MIT for 12 to 13 years and never collaborated with a scientist. I wanted to, but it just never happened.”

Joan Jonas, Moving Off the Land, January 19, 2019, at Cowell Theater, Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture. Photo Credit: Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture/Justine Oliphant For this performance, Jonas worked with David Gruber, a marine biologist at Baruch College (CUNY) who researches biofluorescent compounds in fish. Interested in understanding how fish perceive, Jonas chose to include in her performance video segments of bioluminescent fish taken with Gruber’s “shark-eye” camera, as well as black and white octopus footage shot by Jean Painlevé. The audience seemed amused to see her lunging with open arms toward the sea life as it swam past her on the big screen.

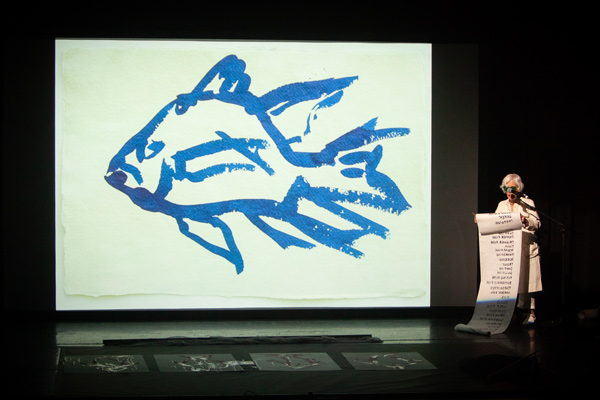

Joan Jonas, Moving Off the Land, January 19, 2019, at Cowell Theater, Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture. Photo Credit: Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture/Justine Oliphant Also on the stage was Ikue Mori, who, spotlighted at the side of the stage, performed music of her own composition with the aid of a computer. Francesco Migliaccio also performed with Jonas, interacting with the video projections employing various surfaces to highlight details of the projected images. Jonas read from a large lectern-type table about the state of our oceans and the impacts of human activity on marine life, including passages from Montgomery’s The Soul of an Octopus, and Carson’s The Edge of the Sea. She also recited a list of species of common fish from a long, handwritten scroll.

Joan Jonas, Moving Off the Land, January 19, 2019, at Cowell Theater, Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture. Photo Credit: Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture/Justine Oliphant The visual crescendo arrived when Jonas used red paint to make four different fish, each held up by Migliaccio, dripping red “blood” onto the floor as the artist recited about the reduction of fish in our oceans. Jonas said that she made this work in an effort to confront the sadness of the loss. “We came from the oceans,” she said, “and our bodies are made of the same elements.” Jonas feels that we carry memories of the oceans in our minds and our bodies. She seeks out ancient indigenous mythologies that speak to a deeper understanding and connection with nature, stories that can alter our relationship with the natural world today. “We are nature,” she said, adding, “I don’t think my work can change anything. But the discussions we are having around it can.”

Joan Jonas, Moving Off the Land, was performed to coincide with the artist’s multimedia installation, They Come to Us without a Word, on view January 17 – March 10, 2019, in it’s U.S. premiere at Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture. fortmason.org

-

Design Crosses Art: SF Art Fairs

Sometimes art looks like design, and sometimes design looks like art. It’s hard to know the difference these days as both artists and designers seemingly want to merge one with the other. Either way, the 5th edition of FOG Design + Art was the perfect hybridization. FOG likes to promote the D for design to attract non art fair patrons; however, the A was in full force this year filling a majority of the 45 booths. The presence of established New York galleries was palpable, among the few booths from Los Angeles and San Francisco, and a sprinkling of international galleries.

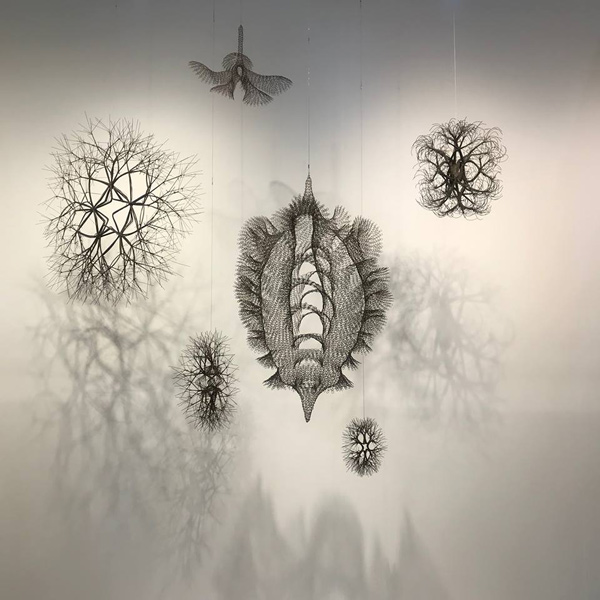

Ruth Asawa at David Zwirner Walking into Fort Mason Center the first gallery you encountered, up front and center, was David Zwirner, from New York, with an unbelievably precious installation of six small tied-and-looped wire hanging sculptures by San Francisco’s beloved Ruth Asawa. The gallery now represents the artists’ estate. Across the aisle was PACE from Palo Alto with show stopping works by Kohei Nawa from Japan of taxidermy animals encased in large glass beads including a deer, a penguin and a baby chick. This was a surreal spectacle especially in the nature rich Bay Area.

Kohei Nawa Another high profile booth from New York was Cristina Grajales Gallery, with four large seating sculptures by Mike and Doug Starn, made from bamboo and rock climbing cords, inspired by their Big Bambú installation on top of the MET in 2010. Marian Goodman presented a large semi trompe-l’œil tree sculpture made from Carrara marble and bronze by Giuseppe Penone. Nicholas Kilner, a design space in Brooklyn specializing in 20th Century Italian artist, architects, and designers, presented unique modernist furniture and lighting fixtures that were of such high quality, they seemed to be awaiting delivery to the nearest museum. Patrick Parrish, although a smaller booth, made a strong but subtle statement with an all black display, including a delicate wire-like sculpture by Julian Watts of Oakland, made from ink stained hand carved eucalyptus. And, one of the more exciting booths from the moment the fair opened was Gavin Brown’s Enterprise with a neon wall sculpture by Martin Creed in glowing letters stating “Fuck You,” which reportedly sold and was removed quickly as it was attracting the selfie crowds, and causing too much distraction.

Blum and Poe from Los Angeles made a big Bay Area statement with a massive J.B. Blunk table formerly owned by Sam Francis. The 1985 hand carved slab of redwood seemed reasonable at $350,000, almost the same price of a large freshly cut Redwood tree. Reform/The Landing, twin Los Angeles galleries that represent several Northern California artists also had a large river rock sculpture on a redwood plinth by J.B. Blunk from 1982, although the nearby c.1960 mobile drink cart by Paul Tuttle, made for Baker Furniture, appeared to be stealing the show. Edward Cella Art & Architecture in Los Angeles presented renderings by Lawrence Halprin, Buckminster Fuller, Neutra and Soleri. Casati Gallery from Chicago showed important work by Italian self-taught artist Carol Rama. And, Volume Gallery from Chicago presented a synthetic long blonde hair wall sculpture by Los Angeles artist Tanya Aguiñiga, which fairgoers could not stop petting.

Tanya Aguiñiga, Papas and Papa (both works 2017). Of the San Francisco galleries included, Hosfelt Gallery presented one of the ultimate examples of artists working at the interstice of design and art, showing several perceptual pieces by Emil Lukas including his thread paintings and hanging tube sculpture. There were thought provoking programs throughout the four days, including panels on female artists rising in representation and marketability, artists as social activists with Theaster Gates, and a provocative public art presentation by Jill Manton discussing plans for the upcoming Treasure Island development situated in the San Francisco Bay. Although FOG is small compared to most art fairs, they still managed to allot space for two smaller cafes and a large dining area (Fog Scape) that occupies at least three booths. Foodies were lined up at all times, often blocking the isles. Compared to your typical art fair, FOG feels like an exclusive luxury living experience. You can even buy earthen dinner plates, as you are leaving the fair, designed by Stanlee R. Gatti, FOG producer and party designer to the mega elite. Very Bay Area.

Last year UNTITLED arrived in San Francisco for its first West Coast edition at the cavernous venue, Pier 70, an undeveloped shipping site in Dogpatch. With the fair came several galleries from around the world that had been unknown to many in the Bay Area. At that moment San Francisco felt like it had finally achieved international status in the contemporary art world. However, for the 2nd Edition, they quickly decided to move the fair to the Palace of Fine Arts, the old Exploratorium space, and closer to FOG at Fort Mason. This year evidenced a greater presence of local nonprofits. It appears a reset was in order.

Onestar Press, Daniel Gordon Gallery highlights included DENK from Los Angeles, featuring work by Tim Hawkinson, including a multi-appendage urethane “thing” of pink mushrooms and a single human hand. Onestar Press from Paris installed a playful installation by artist Daniel Gordon titled Plant & Vase Shop. It included shelves of three dimensional photo sculptures of vases and plants that the artist uses to photograph different still-life compositions, also on the adjacent wall. The Instituto de Visión from Bogata presented work by Carolina Caycedo of London, an ecological neo-colonization plan with hanging netted sculptures retaining natural resources including ore mine-tailing stones extracted from her home country of Columbia.

Kyungah Ham David Zwirner at FOG, was the only gallery that was also at UNTITLED this year. At the Palace he presented paintings by Oscar Murillo from Columbia including several large-scale colorful action paintings with fragments of text and ephemera. Chambers Fine Art from New York was buzzing with fairgoers looking very closely at the pinpricked handmade paper works by Chinese artist Fu Xiaotong. Also mesmerizing were psychedelic needle work paintings, with words and phrases camouflaged inside the embroidery, by Korean artist Kyungah Ham at Tina Kim Gallery. Eduardo Secci Contemporary from Italy presented ethereal semi abstract paintings by Rome artist Sabrina Casadei. They were as colorful and yummy as a landscape of gelati.

Two New York galleries presented work by under-recognized mature artists. Eric Firestone Gallery from East Hampton had a unique work by Howard Kanovitz titled The New Yorkers from 1967, a plex light box with photographic cut outs of the artists’ friends including Alex Katz and Larry Rivers. Todd Merrill Studio included several bold large-scale abstract paintings from the 1970s by Knox Martin, a member of the New York School who is mainly known for his large scale murals.

Jacob Hashimoto, These Strange Galactic Monsters for Whom Creation is Destruction (2017). Zilberman Gallery from Berlin had a large display of diverse ceramic works by Burçak Bingöl of Istanbul, including reworked and compressed clay, sliced, cut, and heavily glazed. Anita Beckers Galerie from Frankfurt had a few transparency light box works by Kota Ezawa, who is also represented by Haines Gallery in San Fransisco presented at FOG. And, Anglim Gilbert Gallery of San Francisco hung a nice display of works by Jacob Hashimoto of New York who makes wall sculpture with a layering of kite-like paper discs tied to wooden pegs referencing Japanese constructions.

UNTITLED offers lots of sensory engagements with art installations, a lounge with couches where you can browse through art books, a bar, a radio station with live interviews or UNTITLED RADIO, and a cinema with films or UNTITLED CINEMA. They even have a booth, UNTITLED POSTERS, that offers free tear sheet posters and plastic covers to carry them in. All these features, organized by curators named on the walls, engendered feelings of special spaces for special people. With so many programs and free spaces to hang out in—and not to buy art—it was easy to forget you were at an art fair.

-

Bermudez Projects: : Cody Norris

“Still Remains” is a small but provocative installation of twenty contemporary landscape paintings by Cody Norris in which the artist responds to the epic disfigurations and loss of wild nature due to extreme weather. Employing a neo-fumage technique, Norris’ work recalls Wolfgang Paalen and his important painting Verbotenes Land (“Forbidden Land”) (1936), a haunting surrealist landscape, considered one of the first fumage painting applications executed almost a century ago.

Cody Norris, I Could Not Foresee This Thing Happening to You (2017), courtesy of the artist and Bermudez Projects. Norris, however, goes beyond using smoke from a flame to mark his oil paintings, although he does that too. He bravely scorches or chars the paintings surface with a blow torch leaving small blisters and patches of crumbling canvas. These slightly disfigured seemingly early 19th-century landscapes represent a range of diverse ecosystems located in no specific place. And, they are not of the mysterious unconscious painting style developed by the surrealists. Instead, his surfaces represent the harsh reality and severity of our current climate crisis, whereas over the last decade wildland fires have more than doubled.

Cody Norris, When All the World Was Green (2017), courtesy of the artist and Bermudez Projects. It makes sense that an artist who was raised by a father working for the US Forest Service would become preoccupied with fire, ignition and suppression. And, that such an artist would become a wildland firefighter who eventually makes paintings about the loss of wild nature.

Cody Norris, You and Me in the Wreckage of the World (2017), courtesy of the artist and Bermudez Projects. Norris’ interest in exploring the emotional ramifications of loss is reflected in the titles of his recent paintings, which excerpt lines from songs, for example: It’s Only Castles Burning (all works 2017) borrows from “Don’t Let It Bring You Down” by Neil Young; I Could Not Foresee this Thing Happening to You, from “Paint It, Black” by the Rolling Stones; and When All the World was Green, from the song of the same name by Tom Waits.

Cody Norris, Descend Through Judgment Valley (2017), courtesy of the artist and Bermudez Projects. The artist, however, is not trying to bring us down with his work; he also posits the question “When we lose a dream, a favorite place, or a relationship, does this always result in a negative balance within us, or can an accumulation of losses result in a gain?” Possibly meaning that after the fires comes new growth or renewal, typically. However, humans cannot ultimately control wild nature, and Norris’ paintings remind us of the unraveling of our dependence on nature as a static romantic experience.

Cody Norris, “Still Remains,” October 7 – November 25, 2017 at Bermudez Projects DTLA, 117 West 9th Street, Space 810, Los Angeles, CA 90015, www.bermudezprojects.com.

-

Water Bottle as Contemporary Artifact

Jami Porter Lara stumbled upon both the subject and the medium of her current exhibition “Border Crossing” at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C., while walking in the arroyos along the U.S./Mexico border in Arizona four years ago. Little did the New Mexico artist know then that she would end up showing this evocative work near the White House, where the sitting president’s focus would be on building a border wall. As she picked up shards of ancient Pueblo pots, Porter Lara noticed what has become the ubiquitous modern-day vessel for water, the plastic bottle—and lots of them. The idea soon dawned on her to combine the old and the new vessels using what she calls a kind of “reverse archaeology.”

Porter Lara came to this series of work after leaving her job as a pastry chef to attend the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque only seven years ago. She quickly learned the technique of Pueblo-style ceramics, a tradition two millennia old, sourcing local clay, soaking, filtering and drying it. To create the vessel body, she forms clay coils, then stacks and pinches them together. After the clay dries she burnishes the surface with a smooth stone and then fires the vessels in an outdoor pit covered with an aluminum tub. The carbon from the smoke then bonds to the clay and turns the vessels black.

Jami Porter Lara, 2016, Courtesy Central Features Contemporary Art, Photo by Addison Doty. The 25 sensuous ceramic creations included in the Washington exhibition refer to water bottles while also suggesting female bodies and body parts—uteri and fallopian tubes, arched backs, arms overhead, and torsos bending. Stretching and turning, thin and thick, the bottles take on anthropomorphic stances. They also seem to be hybridized, with dual orifices and armatures. Yet they each have the standard bottom of the plastic bottle, a pentagram, and the spiraling threads at the top opening, forms that the artist acknowledges have been represented throughout human history.

Over the last decade contemporary ceramics has enjoyed a resurgence. Matthias Merkel Hess in Los Angeles also had lightning-rod success right out of graduate school from UCLA in 2010. He crafted ceramic readymades of gasoline and oil cans, crates, buckets, jugs, blenders, and anvils, seemingly continuing from where Robert Arneson left off with No Deposit, No Return, his pivotal earthenware beer bottle of 1961. However, Hess’ glazes are thick and colorful, whereas Porter Lara, using a more solemn aesthetic, chose to craft an everyday object unglazed as a revered artifact.

Jami Porter Lara, 2016, photo by Geistlight Photography. The series is thought-provoking on several levels. A Mexican-American artist, she is appropriating indigenous ancestral arts. Also, through these works she is addressing plastic’s porosity, which enables the widespread release of chemicals into the environment. And she alludes to the politically charged climate in which parched immigrants cross the U.S. border at great peril, seeking a better life. That’s a lot of discussions to consider when laying eyes on these alluring dark, shiny forms.

-

The Water Bar is Open

A lot has changed over the last two years in the world of water. The high level of lead found in children living in Flint, Michigan—exposed by consuming and bathing in Flint River tap water—was brought to the nation’s attention. And last fall, over 10,000 Keystone Pipeline resisters showed up at Standing Rock in North Dakota to show solidarity with the Sioux tribe protecting the Missouri River. Oil wars logically lead to water wars, and it looks like a time of reckoning is near. What role can artists play in addressing this life-threatening issue? This is a question that often falls flat. Coming up with an arts practice model that serves both educational and aesthetic goals can be a tricky business. In Minnesota, serving free water is what’s on tap.

“Welcome to the Water Bar. Water is all we have,” says the water-tender as patrons approach the bar. When you hear the word “bar” you kind of perk up, thinking alcohol is involved. At this bar, however, you will find a small wooden tray with little compostable cups filled with tap water from various water sources, including small towns, farms and tribal communities. At this juncture you are invited to sample each of the waters to experience their taste and smell, which is a subjective thing since these olfactory senses are very complex and far from uniform.

Colin Kloecker tending bar, photo by Zoe Prinds-Flash Developed as a public art project in 2014 by visual artists Shanai Matteson and Colin Kloecker, the Bar operated exclusively as a pop-up for the first two years, with its big debut at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas. The Bar was placed at the entrance of the Museum’s highly publicized “State of the Art: Discovering American Art Now” exhibition. The following summer Matteson and Kloecker presented another pop-up in Greensboro, North Carolina, at the Elsewhere Museum. This Bar was staffed by a water-tender, a representative from the Greensboro Water Resources Department, who discussed with bar-goers how to protect local water sources. Last October Kloecker was artist-in-residence at Stanford University, where he presented the Water Bar as a program for the exhibition “California: The Art of Water” at Cantor Arts Center.

Dakota Language Society tending-bar, photo Shana Matteson After doing over 60 pop-ups in Minneapolis and venues in Wisconsin and Illinois, the husband/wife duo is currently focused on raising money for their storefront space, located in their hometown of Minneapolis. Formally known as Water Bar and Public Studio, the physical site acts as an incubator for collaborative projects on water, place and environment, all under the direction of Works Progress Studio, a volunteer-run organization. Matteson and Kloecker plan to continue staging pop-up Water Bars in other communities. However, they feel that a local storefront offers more opportunities to build long-term alliances with other artists and water organizations.

Photo by Zoe Prinds-Flash. At each Water Bar storefront and pop-up event a different audience brings its own broad spectrum of knowledge about local water resources. In 2016 the artists started collecting stories in rural Minnesota in collaboration with a statewide storytelling network. They will be sharing these stories at this summer’s State Fair in St. Paul, where they will serve water and converse with over 20,000 fairgoers during the 12-day event. Kloecker explains, “Water is a lens through which we hope to address the rural/urban divide, which is really important.” They have, however, encountered participants who were skeptical of their motives.

Both artists are very political people, although they say the Water Bar isn’t about giving voice to their personal politics or beliefs. “For us, serving water means two things: we serve water to people as a way of encouraging them to slow down, contemplate connections, and better know themselves and their place through that experience. It also means that together with other people we serve water—we are in service to water.” While some artists are on the frontline challenging “the establishment” with scientific ammunition and angry indictments, these artists are wetting their whistle with their potential detractors, attempting to deconstruct in a less contentious environment what is implicit and invisible. There are many roads to Mecca. The Water Bar is one of them.

#refugeeswelcome #waterbar #waterislife #waterisallwehave

-

Mel Chin: Xeriscape LA

Mel Chin’s latest public art project in Los Angeles, The Tie that Binds: MIRROR of the FUTURE, was initiated last summer during CURRENT: LA Water, the city’s inaugural month-long Public Art Biennial presenting temporary large-scale artworks sited along the LA River and in other water-adjacent locations. The biennial came and went via a whirlwind of press events during one of the hottest summers ever recorded in LA. However, Chin’s definitions of temporary, large-scale, and public are concepts that the artist decidedly, and thankfully, challenged, negated, or outright ignored.

Chin is no stranger to breaking boundaries, mixing things up, or waving a flag where no one is looking. With almost 30 years of performing ecologically engaged art in unlikely places, he’s a maverick whom art-world know-it-alls often don’t know. His early soil remediation demonstration project Revival Field, of 1991, explored methods for removing heavy metals from Pig’s Eye Landfill in Minnesota, an art/science collaboration (almost not) funded by the NEA. In 2006 his Operation Pay Dirt project commenced after Hurricane Katrina; it is an ongoing community-based lead-poisoning-education program based out of New Orleans. Discussing his soil work in a video interview with ecoartspace in 2015, Chin stated, “It’s not about chasing down dirty spots, or badness. It’s about approaching the world and being compelled into action.” He added, “I was trying to push forward a new aesthetic that was forming—the aesthetics of our existence.”

Mel Chin, The Tie That Binds (Double Bowtie and South L.A.), 2016. After scouting sites in LA in fall 2015 and making his proposal in February, 2016, Chin received a green light from Bloomberg Philanthropies in March. This left him with three months to install his work before it was presented to the public in July. With such a short time line, and with only one month of public engagement, in all practicality, this might seem impossible. But the real question is: Why would Chin, or any of the artists involved, want to make temporary art with hundreds of thousands of dollars, while addressing water issues in a region that has been suffering a severe drought for six years and counting. Wouldn’t something more permanent or “practical” be more effective?

Chin’s visionary though not-so-easy-to-achieve solution was to create a collective citywide drought-tolerant landscape. To realize this goal, he created eight demonstration gardens, which he sited along the LA River at the Clockshop Bowtie Project, near the intersection of the 2 and the 5 freeways. Using a postwar real-estate developers’ tract “model home” format, he pitched the gardens to potential “customers”—in this case, biennial-goers, to select a “floor plan,” or garden, which they were invited to create for themselves in their own backyard or community space. Willing participants were given a blueprint and an installation manual to execute the gardens. Chin also created “mirror gardens,” replicas of the same gardens at the Bowtie, alternatively sited primarily in the yards of private homes in Brentwood, South LA, Porter Ranch, Sun Valley, and Boyle Heights, as well as public spaces at Occidental College and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

All garden plots are 15-feet-square and are framed like a piece of art with a steel metal border and a standard high-quality edging, mostly recycled/reused and donated by California State Parks. Inside are curvilinear rows of drought-resistant chaparral plants—sages, native grasses, and succulents donated by Village Nurseries. Chin consulted with architects Calvin Abe and Glen Dake on landscape design and plant palettes, and with the Theodore Payne Foundation on plants. The drawings for the blueprints were then created by the artist.

Mel Chin, The Tie That Binds (Brentwood and Double Bowtie), 2016.

Mel Chin, The Tie That Binds (Brentwood and Double Bowtie), 2016. Chin’s The Tie that Binds: MIRROR of the FUTURE was conceived as an emergent and integrative ecological action for LA. The project includes an edition of 512 blueprints for unique gardens, of which 116 blueprints have been distributed to date. Bloomberg funding covered the creation of the eight Bowtie Gardens and the “twin gardens,” as well as the printing of the blueprints. Although there has been no funding yet on the additional 396 unclaimed blueprints or the creation of the 116 gardens from blueprints already claimed, Chin sees this as a long-term project, a common strategy of his. He even created fellowship opportunities with students at Cal Poly Pomona and Otis Art Institute for what he has named the Follow Through Crew. Their role in the coming months will be to support blueprint holders in planting their gardens by offering consulting, home site visits, and documentation. A video is also in development to provide resources for plants and garden adaptations for different soils and shade/sun conditions. In 2017, Chin will continue to identify participants to create his drought-tolerant gardens, with the goal of saving millions of gallons of water annually for Los Angeles. However, as with all of his ecological projects, he states, “There’s a point where you start it, and a point where you must leave it.”

Most of the artists in the biennial created a one-time sculpture or event. While Chin’s approach could be seen as more garden design than art, his blueprints do operate as a kind of artwork or ephemera. Considering the project from a landscape perspective, xeriscape gardening as art is probably more in the realm of environmental education. Although, with Chin’s Tie That Binds, most importantly, he is provoking the public to engage in a collective action, an artwork addressing water issues in their own backyard. This call to action, combining aesthetics and nature in a way that mimics our interdependence, is a “watershed” strategy for ecological art. It is Chin’s modus operandi to make art that contributes to the greater good while, at the same time, questioning the role of the artist and the art. And all the while, he manages to push the boundaries of the very institutions that fund his projects—in this case, using public funds to create art mostly in private spaces.

The Tie That Binds comes during the backlash of “grass wars” gone bad in Los Angeles after the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California rolled out its Removing Lawns Rebate program in 2014. Over a two-year period, the program allocated a large part of the monies to a private company, Turf Terminators, which absorbed millions of dollars and created heat islands by installing gravelscapes, with few drought-resistant plantings. In the end, the program removed almost three thousand football fields of grass, saving 7.5 billion gallons of water, enough to fill 280 Olympic-size swimming pools per year. Yes, the program saved water, although it desiccated the landscape by reducing water retention in the LA Basin. At least with Chin’s vision, we can help mitigate some of these short-term “solutions,” which make for bad landscapes, as well as create a model for public art that can have long-term effects. “The biggest threat to soil is people. Human beings. The track record is terrible,” states Chin. “If we can do one thing, if we can contribute one thing, to be a cog or something in that transformative process, that’s how I see my place in it.”