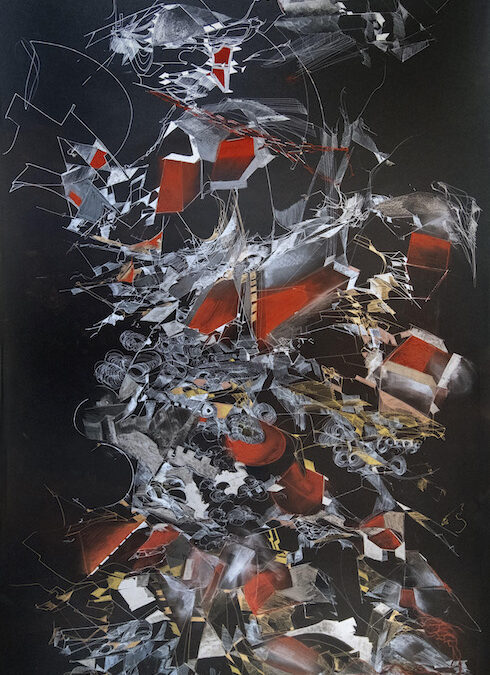

This show at Wonzimer Gallery, organized by contributing artist Marcie Begleiter, is inspired by the Voynich Manuscript, a work that constitutes a parallel exhibition to the show she curated. The Voynich is a mysterious codex from around the year 1410 by an unknown...