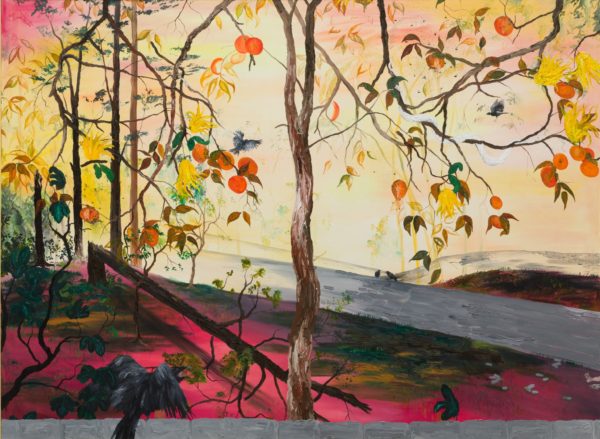

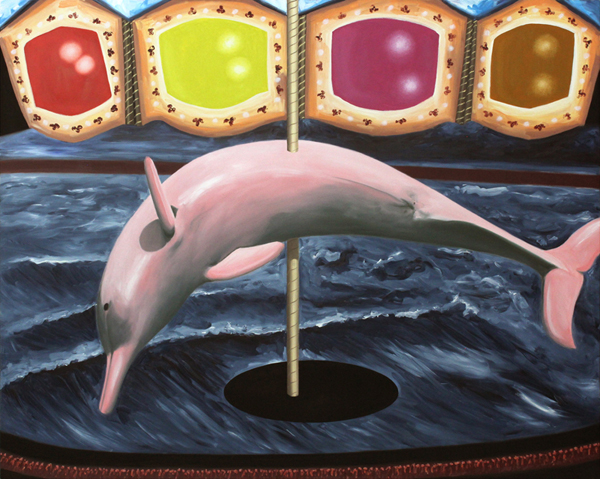

Morgan Mandalay's paintings of tainted jungle paradises are radiant with color and lush verdure, yet they bloom with inklings of mortality. Dead fishes hang amid the umbrage of burning orchards where cadaverous human arms emerge from lurid thickets. Figs and oranges...