Your cart is currently empty!

Burn, Baby, Burn! Bunker Vision

There is nothing new about burning books. There is a recorded instance in the Hebrew scriptures of a scroll, dictated by a prophet, being burned 2700 years ago. Any place that had a written language has also probably had instances of burning whatever the words were written on. It is a testament to the power of language that people in positions of authority feel the need to physically destroy the written word. As technology found new ways to transmit ideas, the objects burned expanded to incorporate them. It was quite common in the 1960s to see records tossed into a fire. The Nazi book burnings were among the most famous instances, but they are hardly an isolated event in history.

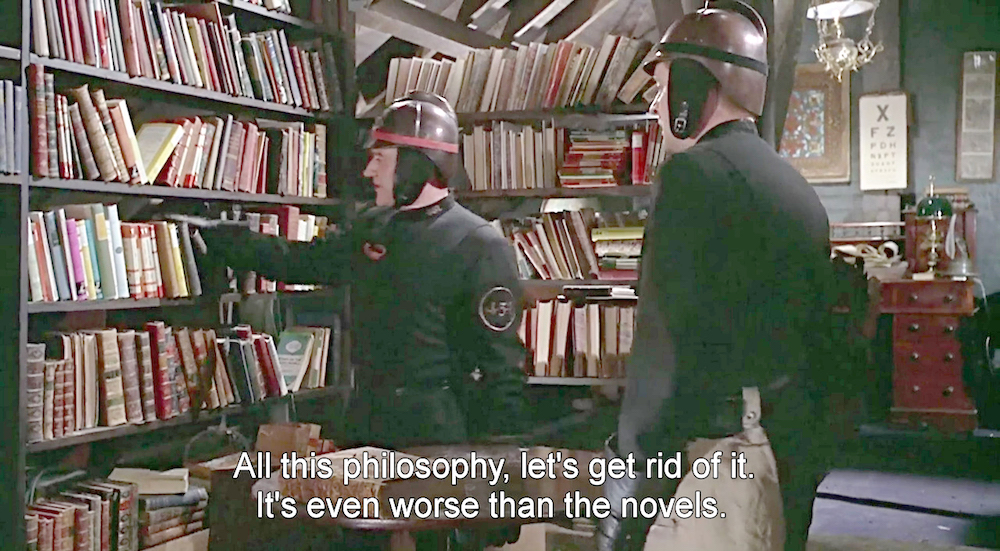

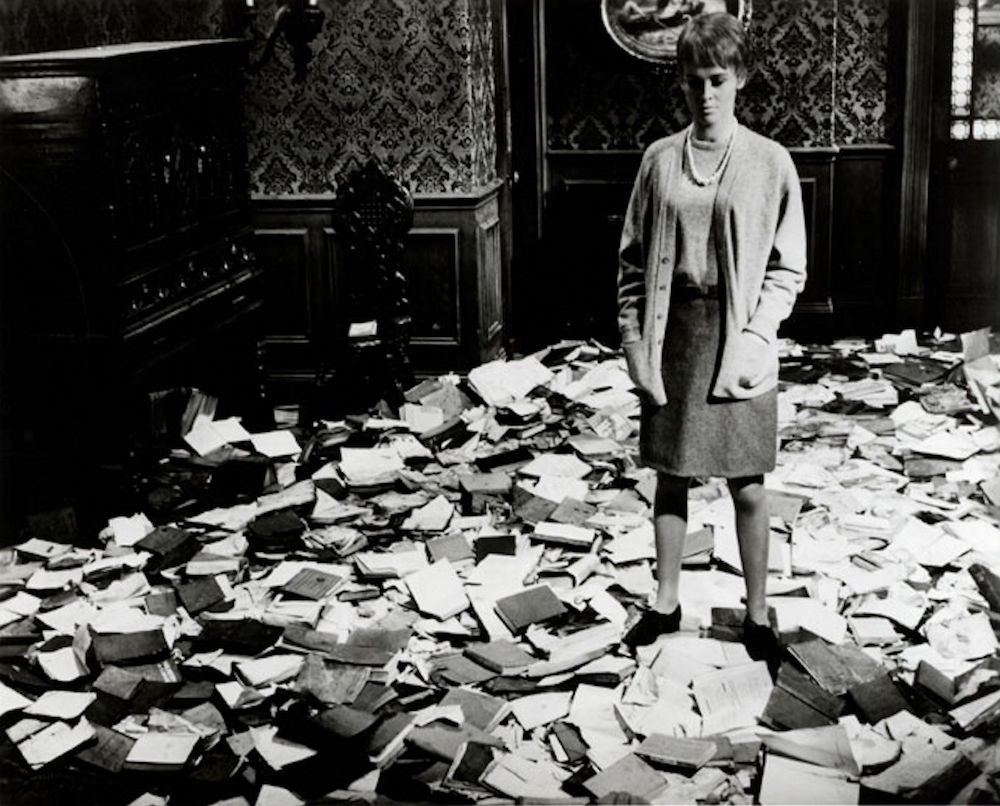

In 1953 Ray Bradbury posed the question: “What if book burning was the official ongoing policy of a government?” His book, Fahrenheit 451, was adapted by Francois Truffaut into the 1966 film. He wasn’t the first art- house director to tackle a dystopian theme. One year earlier Godard had made Alphaville, and three years before that Chris Marker’s La Jetee had appeared. Fassbinder, Tarkovsky and Kubrick would also explore dystopias. What all of these films had in common was the convincing use of an existing world in which futuristic objects, technology and architecture gave the viewer a sense that this was happening in the world that they currently inhabited. Dropping an eye-popping red steampunk fire truck into a ’60s British landscape with a good cinematographer can result in a far more jarring image than anything that CGI is able to produce.

In the world that Fahrenheit 451 portrays, firemen burn any printed words on paper and people who won’t move into a fireproof home are regarded with suspicion. When a woman, who secretly reads, tells a fireman that firemen used to put out fires (not burn books) his first reaction is to question how she knows this. The hostility with which he asks signals his suspicion that she learned this from a book, or somebody who read them.

The immersion into this world begins with the movie’s credits, which are spoken. Newspapers are comic strips without words. Lacking stories, the television programs seem to involve questions of etiquette and gossip. To keep the viewers engaged, the television occasionally addresses a viewer by name. Whether or not they are addressing all of the viewers by name is uncertain, but the featured woman that they address seems like a TV star when she is named.

When a fireman starts reading books that he has been tasked with burning, he starts to question his mission in life. (How he learned to read them remains an unsolved mystery.) He quits the fire department, but is asked to ride along on one last mission. His house is the target. He snaps, burns the fire captain, and escapes to the enclave where the book-people live. Each one has memorized a book, and walks around reciting it. (Bradbury was especially fond of how Truffaut portrayed this scene.) This “happy ending” does raise an interesting question: Without a written version, where a book becomes an oral history, how much of the original book will survive as it is passed to the next generation? Anybody who has ever played the game of Telephone will understand the risk.