The perfect day had been planned: visit the Getty Center in the afternoon to catch the Mapplethorpe show, then stay for the Chris Burden documentary, Burden, with a picnic sandwiched in between.

Viewing the velvety Mapplethorpes became this rich and poignant experience, each image carrying its own message. Every picture told a story, some more than we wanted, some just a glimpse of the plot. The black-and-white photos seeped with variant tones of the grayscale: blacks became rich browns, whites became creams, grays were puce. Altogether made for a muted color circus.

Mapplethorpe’s sculptural flowers

Mapplethorpe’s pictures of flowers resonated in particular for me. His technique challenges the notion of photography: the ability to record the truth. With his lighting, he transforms the entire flower, manipulating its natural beauty into what he wants. He does this with the human body as well. He is the creator, and re-sculpts the object to his liking.

After viewing the rather small but smartly selective Mapplethorpe exhibit, we vowed to see its counterpart show at LACMA, which I’ve been told have even the nastier bits (which is hard to believe as one particular prurient photo still sticks in my mind).

After our picnic we go to the auditorium early as it was chilly outside. Our seats were close to the stage. I decided to visit the Ladies Room and on my way spied Ed Moses being seated with his son Andy and wife Kelly Berg. Coming back I began to see more art-world personalities: Renee Petropoulos, Steve Herd, Jeff Weiss, Jody Zellen, Brian Moss. Downtown LA gallerist Mara McCarthy of The Box showed up with a gaggle of white-haired art-world mavens, some featured in the documentary.

The auditorium began to fill up. Soon it was apparent it was a sold out show, except for the three empty seats to my right. Finally the lights dimmed and the crowd hushed. In an instant flash I recognized it was sculptress Nancy Rubins, Chris Burden’s widow, who was quickly seated right next to me. The lights had not gone fully down and surrounding theatergoers acknowledged Nancy’s presence, turning around to welcome her, giving her a pinch or nod. It was sweet and I could feel the warmth. Meanwhile, I could not believe I was sitting beside Nancy Rubins!

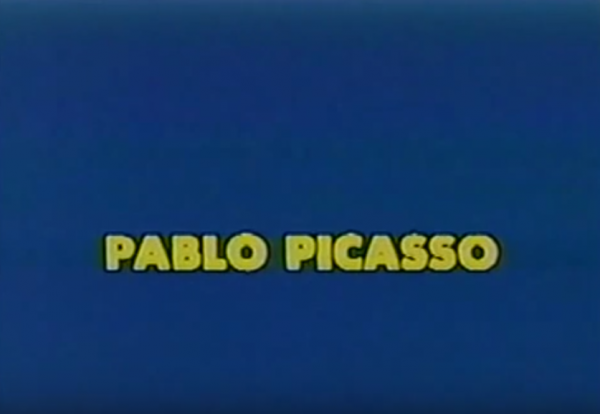

Burden adapts a hilarious tone, featuring a clip early on of his purchase of television air-time in the form of a commercial spot. He inserted his name in a scrolling graphic listing famous artists: Leonard da Vinci, Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso… then Chris Burden. The audience laughs; I hear Nancy quietly chuckle. I felt this early piece of Burden’s was most telling of his whole reason for making art: making his mark in art history.

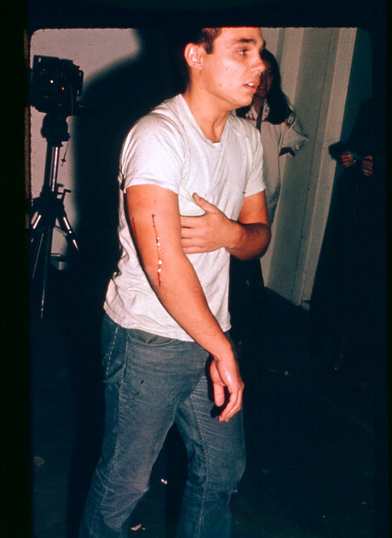

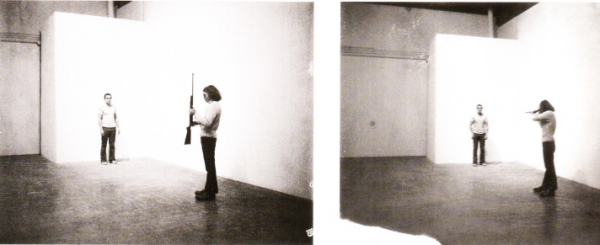

Shoot, 1971

The documentary by Timothy Marrinan and Richard Dewey focuses primarily on Burden’s early work, and perhaps rightfully so. What else is there in between? Burden’s greatest hits, Shoot and Five Day Locker Piece (both in 1971), his 1974 Volkswagen piece Trans-fixed are all there, with plenty of visuals and backed-up comments from noted artists. Food critic Jonathan Gold even chimes in with stories from the time he spent as an early assistant to Burden. Minimalist painter Charles Hill offers delightful anecdotes of Burden, one in particular describing Burden as a jilted lover renting a semitrailer amped up on alcohol and drugs to stalk Alexis Smith in the desert. Burden’s first wife, Barbara Burden got a fair amount of play also, mainly as a supporter, emotionally and financially. Most noticeably missing was Nancy Rubins, my theater neighbor!

Burden in his latter days in front of Metropolis II

Urban Light, 2008

The film was entertaining enough and informative, but lacked a clear narrative for Burden’s entire career. It didn’t really explain his leap from his early violent works to his street lamp installation at LACMA (Urban Light, 2008) and how he was able to retire on a Topanga ranch. But it was good enough to remind me of Chris Burden, the conceptualist artist who really started something and maybe got his name after all on that long list of famous artists.