Your cart is currently empty!

BUNKER VISION

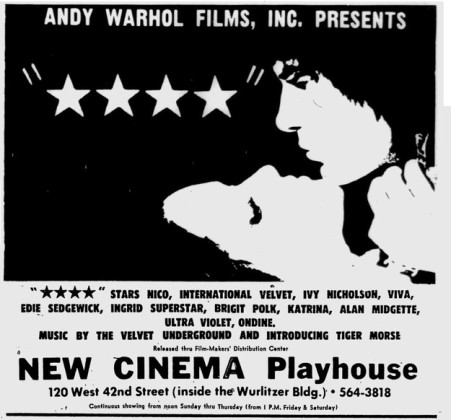

Long films aren’t new. As early as 1914, there was a film (The Photo-Drama of Creation) that ran eight hours. Wikipedia lists at least five films from that decade, which ran at least six hours. In 1971 Jacques Rivette made a famous 13-hour film (Out: One) that had one screening in the ’70s. (It’s now a regular at museum screenings, and due for a DVD release). Andy Warhol made a film in 1967 called Four Stars that ran 25 hours. The current record holder seems to be a 240-hour film called Modern Times Forever (2011). But records are made to be broken.

Swedish artist Anders Weberg is about to up the ante. After a 20-year career in film (experimental projects and pop music videos) he is about to make his last film. It is set to run for 720 hours (one month). It will be screened simultaneously on every continent starting on December 31, 2020 after which all copies will be destroyed. He posted a 72-minute “trailer” online in 2014. In 2016 he plans to post a seven-hour-and-20-minute version, and in 2018 there will be a 72-hour preview.

As he points out, nobody can watch the whole thing in one sitting. (The record for movie-watching is held by an Indian man named Ashish Sharma, who managed to watch 120 hours with only 10-minute breaks between films.) The filmmaker will be the only person who actually sees every frame of film. He claims to have a sense of what will occur during the finished film. He is billing it as a sort of “film memoir” that deals with his relationship with the moving image, which he characterizes as “having lost the lust for.”

This is not his first time using ephemeral concepts. His CV includes: “inventor of an artistic process called P2P” which he describes as: Art made for—and only available on—the peer-to-peer networks. The original artwork is first shared by the artist until one other user has downloaded it. After that the artwork will be available for as long as other users share it. The original file and all the material used to create it are deleted by the artist. ”There’s no original.”

One of the interesting ideas that fuel this piece is the concept that digital things are harder to delete than to create. He compares this to the analog world where things can actually be “broken or burnt.” Much of his work deals with identity, so ending his film career with a memoir is in keeping with what went before. And though he is ending his work in film, his art career will soldier on. Each month that he films, he produces a series of “film stills” in editions of 100. He is also available for lectures. As a marketing tool, retiring to the lecture circuit after making the world’s longest film is a pretty smart move.

Comments

One response to “BUNKER VISION”

Hi,

Thanks for sharing this.

Anders