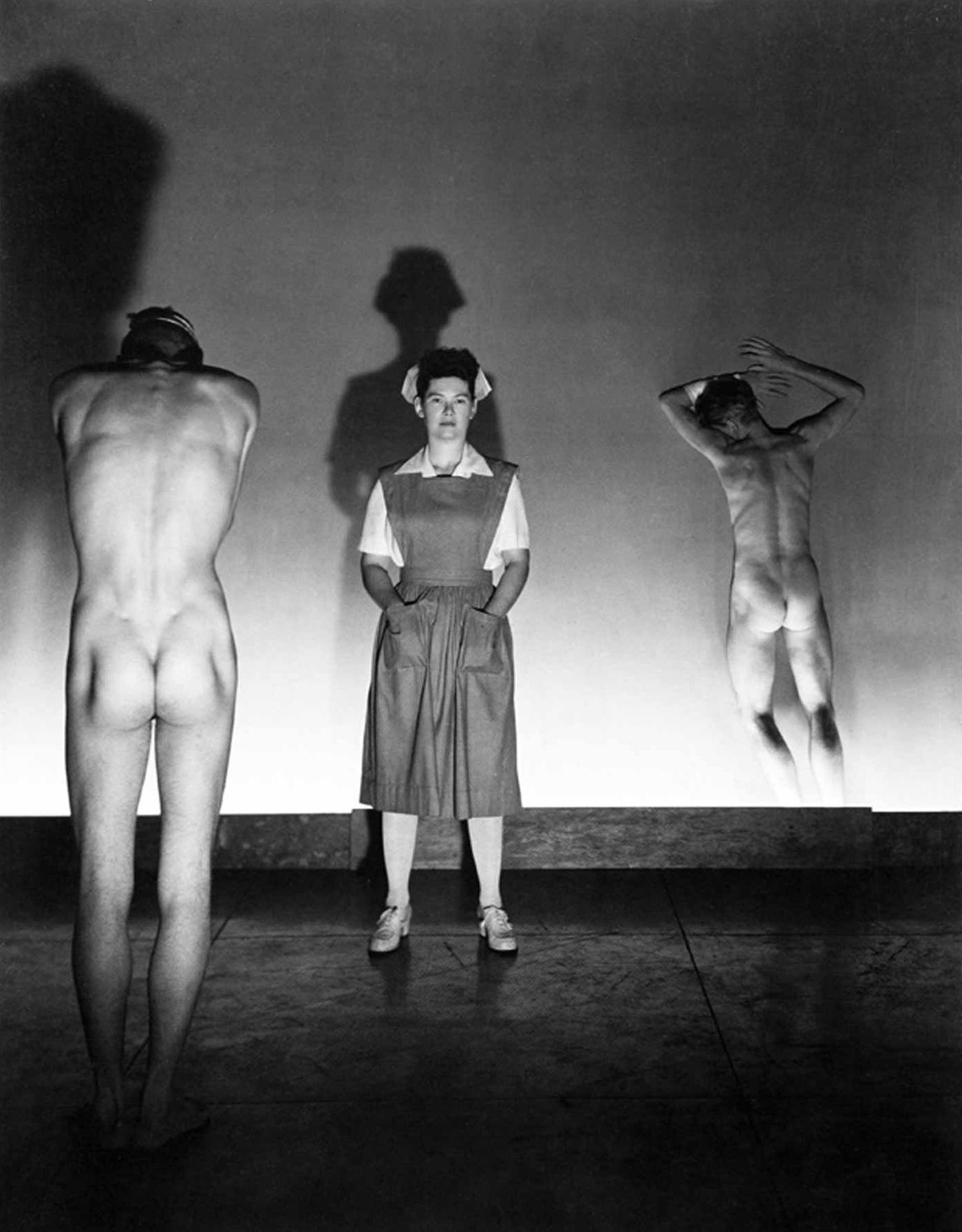

In 1981 a new photography monograph appeared that seemed like an artifact from a parallel universe. The cover was a studio shot of a nurse flanked by two nude men. Many of the photos in the book depicted nude men in potentially gay scenarios. It had only become legal to mail this book in the United States ten years earlier. If you were a scholar of the history of photography you might have recognized the photographer’s name from his portrait and ballet photos. But this work caught the world by surprise. Although beefcake photography had been published before in magazines, none of it had the look of something that had been produced by a movie studio. Suddenly people wanted to know who had taken these photos. Unfortunately, the photographer had died 26 years earlier, and hadn’t been famous enough to merit a biography while he was alive. Thanks to an admirable feat of detective work, we now have a pretty detailed account of the photographer’s life.

George Platt Lynes didn’t start by wanting to be a visual artist or photographer. His heart was in the written word. He initially aspired to being a small press publisher and an author. He even owned a bookstore at one point. His original reason for taking photos was to hang them in his bookstore. His love of the written word was on display in the constant flow of letters that he sent and received. On a family trip to France when he was 18, he managed to meet Gertrude Stein. A rich source of material for this book comes from his brother, who wrote an unpublished autobiography of George in the spirit of Stein’s Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. Anybody who is interested in Stein lore will get an interesting perspective of a not yet famous Stein hustling Lynes to get her a publisher (or to publish her himself). George became a regular visitor to Stein’s salons, which caused him to photograph all of the famous people he was meeting. He took what is considered one of the seminal portraits of Stein. Her salon launched him into the right circles, and one of his publishing ventures included a book by Ernest Hemmingway.

Although he was born in 1907, he never seems to have been in the closet. His father was an attorney who became disenchanted with the law and became a minister. He managed to get postings to good neighborhoods, so George grew up in nicer surroundings than a minister’s salary might afford. His mother had a teaching degree, so both parents had experienced higher education. His father loved opera and had worked as an usher during his theological training in order to watch operas for free. As he came into his own, George was an avid attendee of operas, ballets and plays. When he proved to be less overtly manly than his juvenile peers, he would claim to be a Russian prince, whose identity was a highly regarded secret. His parents, sensing that he was different, decided to send him to boarding school in order to offer him some male role models. The school called their approach “muscular Christianity”. Various teachers and classmates compared him to Oscar Wilde, and classmate Lincoln Kirsten remembered him as a “foppish freak”. Once his father was resigned to the fact that his son wasn’t going to pursue a traditional career, he gifted George with his first professional camera.

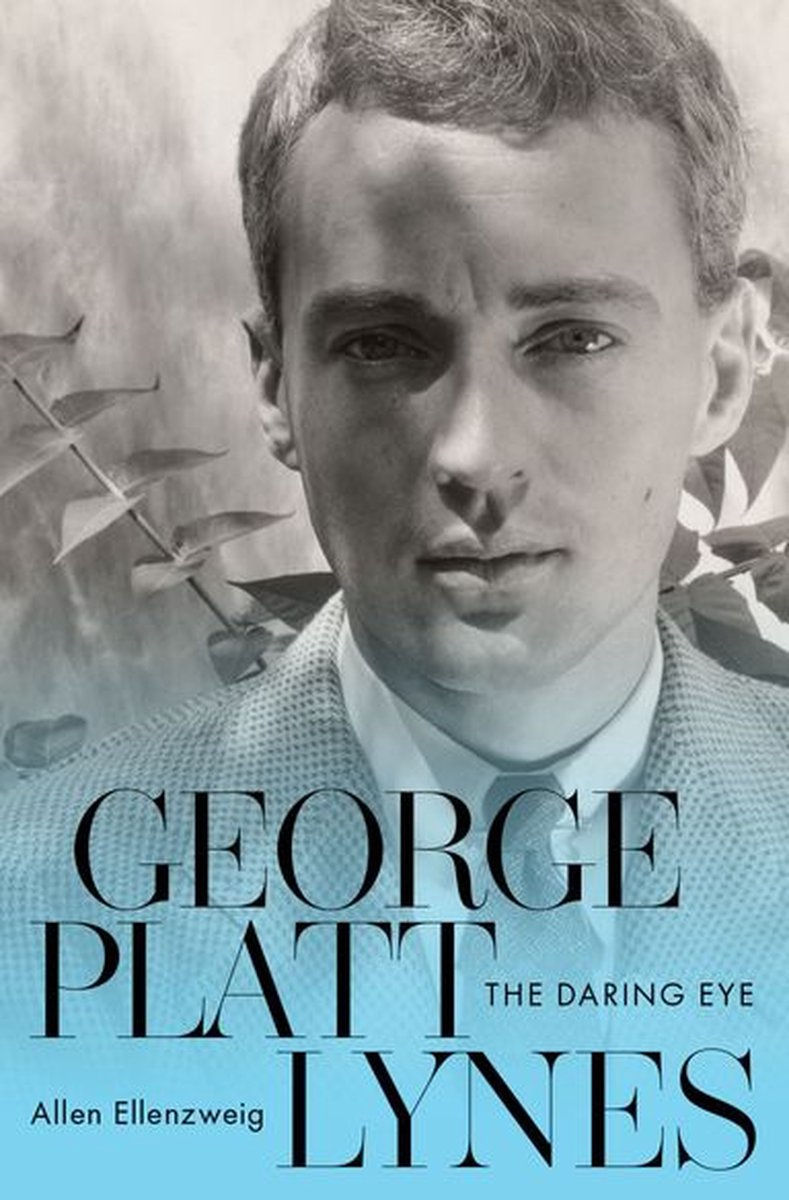

Cover image of the book.

At the tender age of 20 he met and fell in love with author Monroe Wheeler. The problem was that Wheeler was already devoted to another man. George solved the problem by grafting himself onto the existing relationship, making them an early throuple. Once they all decided to live together, their apartment became ground zero for the smart set in Manhattan. The relationship lasted for nearly 20 years. His earliest photographic work was portraits. He had access to a who’s who of the mid 20th century, and his social whirl always had a bit of calculation about who might sit for a portrait (or take off their clothes for a more private photo. He convinced Tennessee Williams and Yul Brenner to pose naked) He paid the bills by doing fashion photography, and his ballet photography brought in income. Money was always an issue. First his father and then his younger brother were often called upon to keep the wolf from the door. It can be head spinning to read that while he is up to his eyeballs in debt, he needs to run home and change into his top hat and tails for the opera.

Eventually the IRS ended his long streak of good luck. In 1952 the entire contents of his studio were auctioned off to pay back taxes. (Richard Avedon ended up with his studio) His younger brother brought in proxy bidders to buy back his camera and essential equipment. But he never recovered his mojo, and died within three years of lung cancer. Sensing his own mortality, he made arrangements to place the nude photo work with the Kinsey Institute.

This book is rich in details about his life and the world that produced him. It is the sort of book that you can open to a random page and be caught by some detail that will have you racing to Google to learn more. There are photos throughout the book that offer relevant visuals. The footnotes are copious and often fascinating in their own right. For anybody looking to study or recreate gay life in the mid 20th century, this is a deluxe road map.

George Platt Lynes: The Daring Eye

by Allen Ellenzweig

664 pages, illustrated

Oxford University Press