Your cart is currently empty!

BOOKS: Billion Dollar Painter

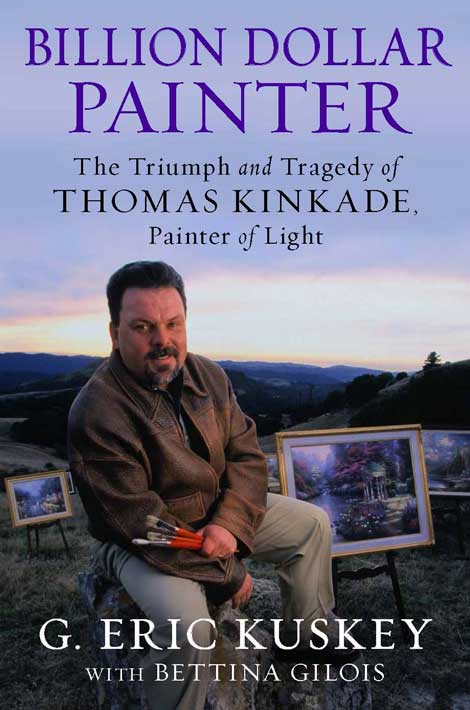

If you asked beginning art students to name a living artist in 1998, the most frequent reply would be Thomas Kinkade. Given the art world’s fascination with popularity and money, this is hardly surprising. By this point in his career many upscale malls had galleries devoted to his art (which, as this book points out, were as carefully planned as a Disney ride). It was also calculated that at least 1 in 20 American homes featured something by Kinkade on their walls. Kinkade’s long-awaited biography Billion Dollar Painter, was written by the man responsible for licensing his images, G. Eric Kuskey.

Kinkade loved the idea of licensing. To him it was a way for more people to experience “the messages” in his art. These messages often took the form of Bible verses that were hidden in the imagery. His core audience was conservative and Christian, as were the investors who ultimately felt betrayed when his expanding gallery empire left a trail of bankruptcies as his market became oversaturated.

The only place he ever really felt at home was at his easel, painting. Painting helped keep the demons at bay, and it paid for a sense of security that his early years lacked. At his peak, original paintings (he produced 12 to 15 a year simultaneously, so that the layers of oil paint could dry between applications) sold for $500K to a million dollars each. He invented a trick that would have made Andy Warhol jealous. After having copies of these paintings applied to canvases, painted highlights were added to make each work an “original painting.” There were even multiple levels of “original” depending on who applied the highlights. A few dabs of paint, hand-applied by Kinkade, added about $20,000 to a canvas reproduction.

If his factory approach to art seems Warholian, it did not go unnoticed by Kinkade, who cited Warhol as a major influence. He went so far as to compare his flaming cottages (as Joan Didion described them) to Warhol’s Brillo boxes and soup cans. His fervor to share his vision, along with the profit fever (he morphed himself into an investment vehicle, Media Arts Group, listed on the NY Stock Exchange in 1988) caused him to create “editions” that were too large to actually sign. This issue was resolved by including a drop of his blood into the ink used to print his signature. At the height of his empire, loading docks in warehouses the size of multiple football fields were stacked ceiling-high with framed editions packed in cardboard boxes.

His story begins in a single-wide trailer, where he and two siblings were raised by their mother only. A recurring motif in tales of this period involved watching to see if mom had any groceries with her when she returned home from her jobs. He lived the rest of his life in fear of losing everything. He attended UC Berkeley at the recommendation of the artist Glenn Wessels, who he had been assisting. From there, he went to Pasadena Art Center.

His first brush with success in the art world involved coauthoring a how-to-sketch book with a college friend. It was done as a work for hire, so he didn’t benefit from its staggering sales. When he started showing his canvases at local art fairs, he was spotted by a champion vacuum-cleaner salesman, who decided there was more money to be made from art than appliances. Assuming that the business end of things was covered, Kinkade retreated to his studio, emerging for the occasional business meeting or personal appearance. His trust was ultimately misplaced, as more people from the vacuum company joined his business team.

Once Kinkade’s name was trademarked and his image became part of the package, his drinking started to take its toll. He would drink to a state of blackout, prompting a number of inappropriate actions, such as groping his conservative Christian female investors and urinating in public. He celebrated a Disney deal by pissing on a Winnie-the-Pooh statue, screaming: “This one is for Walt!” One of his most notorious blackouts involved him standing in the front row of a Siegfried and Roy show screaming the word “codpiece” over and over.

When Jeffrey Vallance curated a selection of his work at CSUF Grand Central in 2004, he was convinced that a major museum had finally given him the retrospective he deserved. Shortly after this occurred, the galleries started to feel the effects of an oversaturated market, and the lawsuits commenced. In 2010, Kinkade’s wife of 30 years staged an intervention, declaring either it was her or the booze. He picked the booze and careened further out of control. Having mortgaged everything to settle the many lawsuits, he died cash poor of drink at age 54. Billion Dollar Painter is a cautionary tale told well, with a fine balance of sympathy and objectivity.

Billion Dollar Painter: The Triumph and Tragedy of Thomas Kinkade, Painter of Light

by G. Eric Kuskey with Bettina Gilois

On Sale September 9, 2014; Weinstein Books. $26

Comments

4 responses to “BOOKS: Billion Dollar Painter”

Complete distortion of the facts by this idiot Kuskey. He had not been part of the company since 2000 and was not friends with Tom for the last 13 plus years. For someone who didn’t like the strategy he certainly put Thom’s stuff in every possible outlet he could find. Eric and Thom shared one thing……Greed

I have read this book and it is mainly filled with lies and distortions. First of all Kuskey was fired. Second Kuskey and the others he mentioned including Raach, Byrne etc were in charge when the company LOST 10 M dollars in the fiscal year…Kuskey and others were fired including virtually all that he credits with building the company. When new management came in, the company became very profitable.

Go ahead a waste your money on this book. You will be reading mainly distortions, false recollection of the facts and some out right lies.

I would have loved to see his work depicting his struggles rather then his fluffy fairytales.

Just finished this book this morning.

I loved it!

Made me cry at the end with the impact of the story of this man.

I feel it was very well handled, a good look at what can go wrong when something special is in the wrong hands, a good marketing look at the effects of pressures on a company from Wall Street, a good discussion on what is great art, a great depiction of the effect of art and the needs of people, and a beautiful look at a pure artist and special being who lived doing what he was put here to do – touch people through the light of God.

I wish those responsible had just reimbursed gallery owners, instead of fighting them, also that they went back to being private a lot earlier, then all would have been different. That’s the tragedy and makes for a moving story.