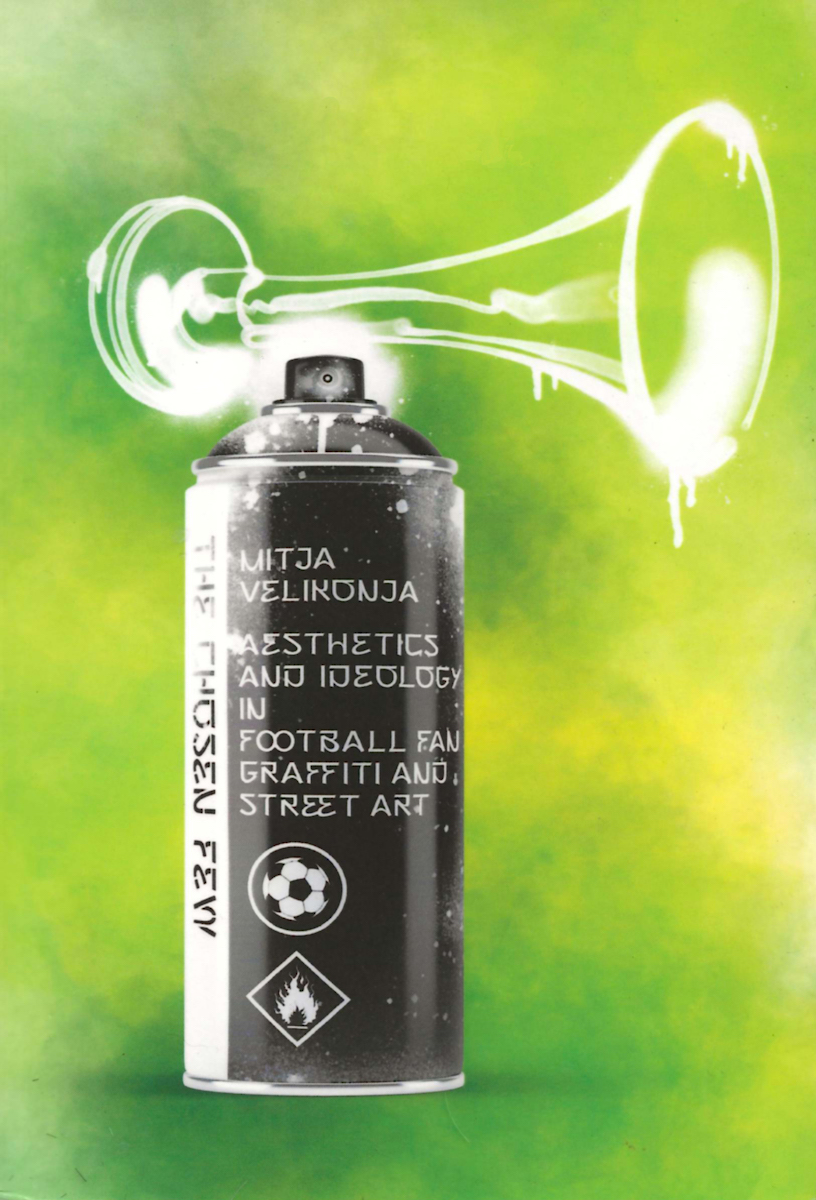

The Chosen Few: Aesthetics and Ideology

in Football Fan Graffiti and Street Art

By Mitja Velikonja

176 pages

DoppelHouse Press

Graffiti and street art are often considered synonymous since they affect the urban environment in similar ways. But graffiti is onomastic: the essential purpose is to advertise one’s presence; it’s the big “I am” that challenges metropolitan anonymity. That is also achieved with latrinalia, slogans and phrases that serve as necessary disruption of daily life. Graffiti is a platform for outsider political and social activism among those who consider themselves silenced or purposefully omitted from larger societal colloquies.

Unlike street art, which is generally sanctioned and can remain an element of the street for an extended amount of time, graffiti is illegal and temporary. Consequently, some writers and sticker-bombers prefer membership in a group from which graffitaro can anonymously promote that to which they pledge allegiance. In Europe, soccer fans known as ultras typically design and produce their own stickers, pasteups and wall pieces promoting their favorite Football Club (FC). These remarkable DIY designs are featured in Mitja Velikonja’s scholarly illustrated book The Chosen Few: Aesthetics and Ideology in Football Fan Graffiti and Street Art, which examines the relationship between European soccer teams and their graffiti-oriented, street activist fans.

Velikonja posits that sticker bombing and stenciling reveal how soccer fan graffiti is never ideologically neutral or apolitical, and the statements being made often cover more than a single issue. The observation that soccer is a “means by the powerful to pit workers against workers in competition and as a potential tool for nationalism” means that in some cases the graffiti is about intense societal differences as well as sports rivalry. In The Chosen Few, Velikonja discusses such direct display of political preferences and values, as well as fans’ self-image and the recognizable aesthetics of their stickers or stencils.

The Chosen Few book cover, image by Tauras Stalnionis

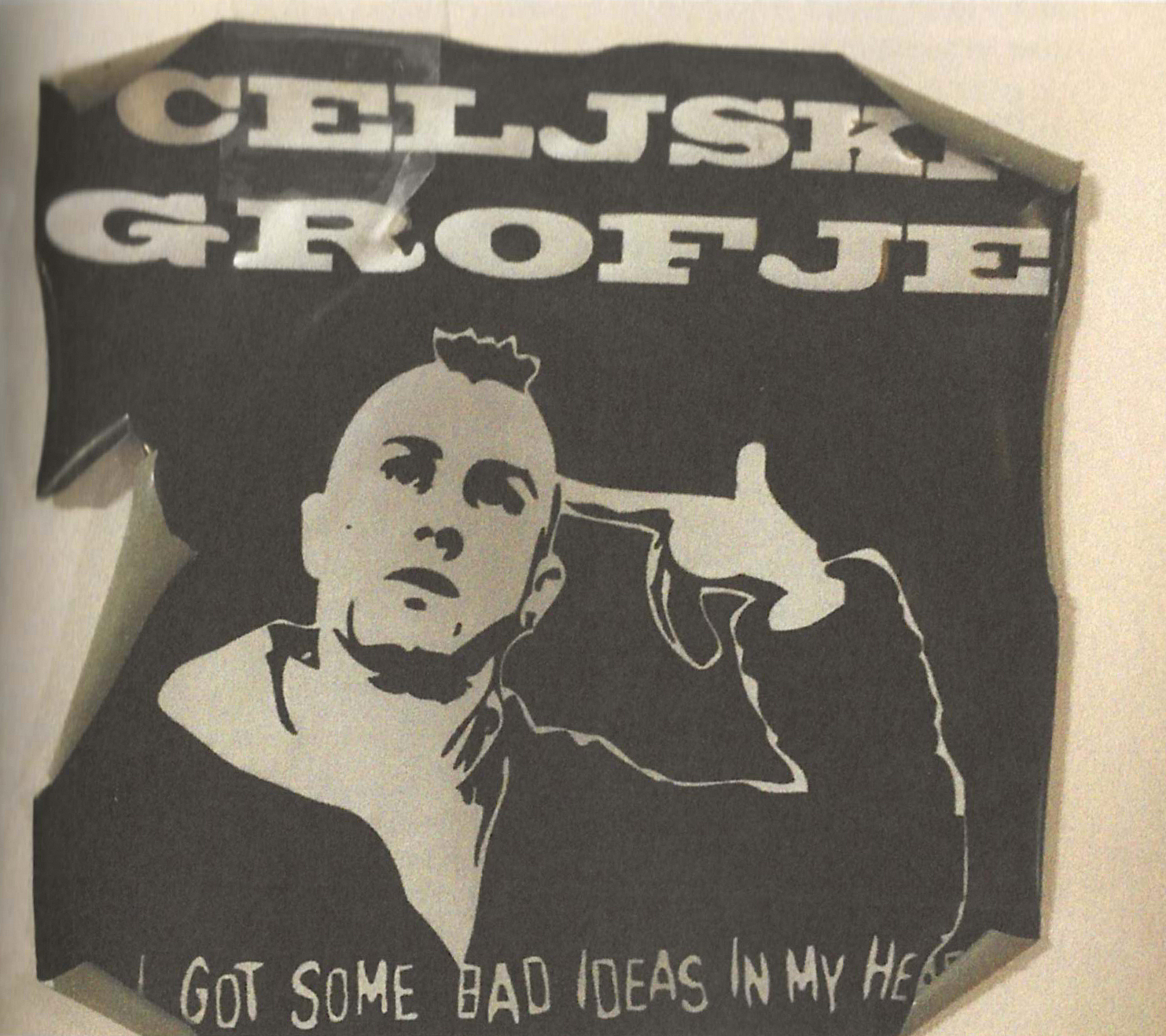

Much of the graffiti and street art in The Chosen Few relies on altered versions of iconography already familiar to the public. This ensures that passersby, attracted by the striking image, will examine the sticker long enough to parse that it’s promoting a specific soccer team. For example, one sticker bomber fan of Slovenian Celje Football Club uses a metonymic image of Travis from the film Taxi Driver and the line “I got some bad ideas in my head” to express their disdain for other teams and non-fan society in general. The negative side of this “economy of means” is that present-day advocates of the extreme right resort to displaying swastikas and other Nazi symbols to promote their favorite soccer club, even though ironically, that team might have nothing to do with such ideology.

Although graffiti is an ancient method of visual communication, it is only in the last 20 years that it has matured to become a familiar element of self-expression in the urban arena. Consequently, Velikonja’s analyses are an essential addition to any discussion about the connection between football and graffiti, as well as its effect on social affairs in the streets. To be sure, an abundance of facts is necessary to support a thesis, but in this case it weighs down the fascinating nature of the subject. Velikonja’s exhaustive research makes The Chosen Few so dense that, while a compelling read, it could use a little more about markers and less about Marx.