There’s a picture that photographer Virginia Liberatore took of painter Jean-Michel Basquiat and Madonna in 1983. The two stars, who were dating at the time, had arrived at a party in full regalia—fedoras, big watches, leather jackets. In the image, Madonna resembles a cat, making a claw out of one hand and eyeballing the camera like a pretty predator. But Basquiat looks anxious and slightly blank-faced, as if he had just been stunned by a blow. His affect might be explained by the fact that the same year, his close friend, the black graffiti artist Michael Stewart, had been killed while in police custody: The authorities listed the cause of Stewart’s death as a heart attack, but an independent pathologist said he succumbed to strangulation. Liberatore’s is a mesmerizing document, capturing Madonna’s glamorous obliviousness and Basquiat’s inability to stay on brand while enduring the grief and shock that flows from racial violence.

DJ Michael Stock

These same dynamics—fake vs. real, professionally chic vs. awkwardly authentic, insistently social vs. helplessly alienated—churned through the Broad’s last summer Happening, which was dedicated to Basquiat’s art and life. Basquiat began with visual artist and musician Damon Locks’ ambitious sound piece interpreting such paintings as Air Power (1984), which depicts a hatchet, an old man, a windmill, and a helicopter: Locks sat at a table in the Plaza, washed in violet light, as he played a series of stinging guitar licks off of a synthesizer and repeated phrases such as “his mother tongue is power.” Locks’ words offered a necessary reminder on a day when failing to perform the expected words or gestures (by, say, taking a knee) could earn a black man curses from the highest office in the land. As such, Locks started off the night on a high mark that proved hard to beat.

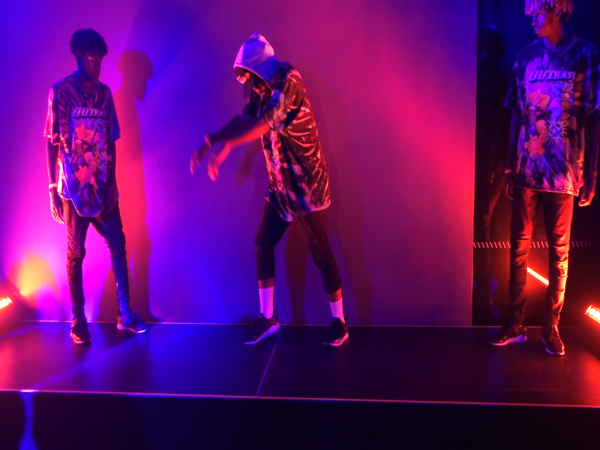

DJ Michael Stock

His act almost was bested, though, by the dancers performing with DJ Michael Stock in the Oculus Hall. Stock, a punk specialist and DJ, played high-octane rhythms combined with ghostly vocals in the shadow-filled space. Bright purple and green lights flamed on James Thomas, Brandon Hunt, and Tavares Marshall, who mixed robot paces and literally deconstructionist popping to create a dance form that we here at Artillery had never seen before. Some of the performers were so double jointed that they could replace the ordinary ball-and-socket ergonomics of the human skeleton with something less banal: They sinuously cracked their bodies apart, reconfiguring their shoulders and hip joints so that they embodied creative contingency. Their performance reminded us of the human condition, illustrated by Basquiat’s shattering art, which requires us to destroy old, supposedly necessary models in order to fashion new approaches to the troublesome future. That the dancers enacted these themes while also swiveling gracefully to Stocks’ jams made them, for us, the #1 genius dancers that we have seen all year.

Zebra Katz

Our joy at these two performances, however, proved slightly tempered when Zebra Katz took the stage on the Plaza. Katz, the stage name of performance artist Ojay Morgan, is a talented and “other” queer rapper who has forged identities and artforms with some of the same audacity as Basquiat himself. We were thus extremely excited as we began to make shapes to Katz’s innovative raps on the Broad’s lawn, until we realized that a great many of the words in Katz’s songs were actually just one word, and that word was “bitch.” Katz’s music often engages this epithet. Katz used it in their 2012 hit Ima Read, where they promise repeatedly to “take that bitch to college,” which does not seem to be a promise to provide financial aid, and in 2014’s 1 Bad Bitch, whose video shows Katz’s alter ego murdering four rich white women and then transforming them into taxidermy. Katz has acknowledged their indebtedness to this particular trope: “It’s seen as a very misogynist word in hip-hop but we’re trying to numb it,” Katz told The Guardian in 2013. As we danced to the anesthetized sexism, we here at Artillery tried to be cool like Madonna in 1983, when she didn’t make a political fuss and was just an adorable fun cat. To calm ourselves down, we attempted to read Katz’s deployment of “bitch” in the loving spirit of radical feminist Mary Daly, who in her Wickedary defined “bitch” as a moniker earned by “lusty” and “scary” women. We also understood that “bitch” can operate as a floating and multidimensional signifier. But, then, we realized, the taxidermy and murder stuff might suggest other, more conventional meanings. We continued gamely Macarena-ing through these doubts, but eventually we began to feel like a patsy and a hypocrite. We also wondered whether “numbing” was the wisest art practice, and had a bad flashback to Basquiat’s face in the Liberatore photograph. Then we wished we were back with Damon Locks so that he could make us interrogate power in ways that didn’t seem to suggest our own personal debasement.

Shani Crowe

The anxiety we experienced during Shani Crowe’s performance in the Lobby proved of an entirely different quality, informed more by knowledge of the California Penal Code than of radical Wymynism or the painful revelations of structural and political intersectionality. Crowe is an interdisciplinary artist from Chicago, and she experiments with cultural coiffure and beauty ritual in order to narrate the diaspora and also foster connectivity. In the lobby, she kneeled on the floor and began to arrange strands of red, green and black fibers around her body. To her left stood a tall structure around which had been arranged a cape of painted paper. Crowe tied back her hair into a tight ponytail and then began to laboriously braid a heavy 15-foot extension onto her head, using the colorful fibers. She next stood up, walked over to the paper-enclosed structure, and ripped off its covering. In so doing, she revealed a man crouching at the bottom of a kind of scaffold. The man wore no clothing but BVDs and appeared to be Anglo. Crowe then yanked the man to a standing position, lashed him to the scaffold, and proceeded to energetically flagellate him with her long braid. She hit him repeatedly and hard enough so that red stripes began to puff on the skin of his shoulders and spine.

Mecca VA and the Movement

We were able to read complicated meanings in this thrashing, which included not only an ode to the hopeful pleasures of BDSM and a critique of racist beauty standards, but also maybe Crowe’s retaliation for slavery and its atrocities. We stood in the crowd and looked mostly at Crowe’s colleague, who shuddered at every clout and bore an agonized look upon his face. We were very sure that he must have autonomously chosen to have occupied this contested position. Many people like to be whipped and this was art and he could call out for help at any time, we reassured ourselves. We attempted not to worry about the amorphous and often illusory nature of free election, which so often rests in the messy bed of imperfect agency, that human paradox of experiencing one’s liberty and one’s oppression at the same time. We were confident he must have a safety word. His back looked sort of injured. He probably also signed a non-binding waiver and had consulted with his psychiatrist and his lawyer before getting his ass beat in front of a bunch of strangers. That these strangers also had begun whooping and laughing at his abuse should not have deterred him from choosing to put a stop to the performance if he so desired, right? What was the crowd guffawing about, anyway? Now staring up at the jeering throng with which we mingled, we feared that our admittedly sporadic adherence to ahimsa might be interfering with our role as an art critic. And then, we also remembered that CPC sections 31 and 242 prohibit the aiding and abetting, that is, the encouragement, of non-consensual battery.

Jay Carlon

Standing by silently was not encouragement but it also seemed bad. So we slowly stepped back from our front-row position, disappeared into the crowd, and continued to overthink everything on our way to the third floor to see the Jay Carlon dancers, who twisted and floated among the Broad’s Kara Walkers and the Basquiats like troubled gods. One woman with cropped hair and mustard trousers curled up on the floor, and then stood up and spun around until she felt dizzy and sick. She staggered around the gallery as if she might throw up.

We drifted outside to see The Downtown Boys play on the Plaza stage. The female singer wore a floral crown and bashed around, yelling “this is for everyone who ever did something they thought was impossible and wasn’t blunted by capitalism!” before breaking out into rock songs from their 2015 opus Full Communism.

We nodded our head along to the tunes, but felt the whiplash of participatory exegesis. Getting insulted, flirting with felony liability, and watching people dismantle themselves and barf is not, for us, a typical Saturday night. Was it all concocted and fake, like Madonna? Or were the performers and the crowd overwhelmed, like Basquiat?

We didn’t know. As we walked around the Broad’s fairy-lit campus, the evening air blew cool, and filled with chatter about police murders of people of color, black art, white money, nuclear war, feminist linguistics and celebrities.

And on these notes of engrossed bewilderment and psychic electrocution, came a close of the Broad Summer Happenings for yet another year.

Photos by Chris Jarvis