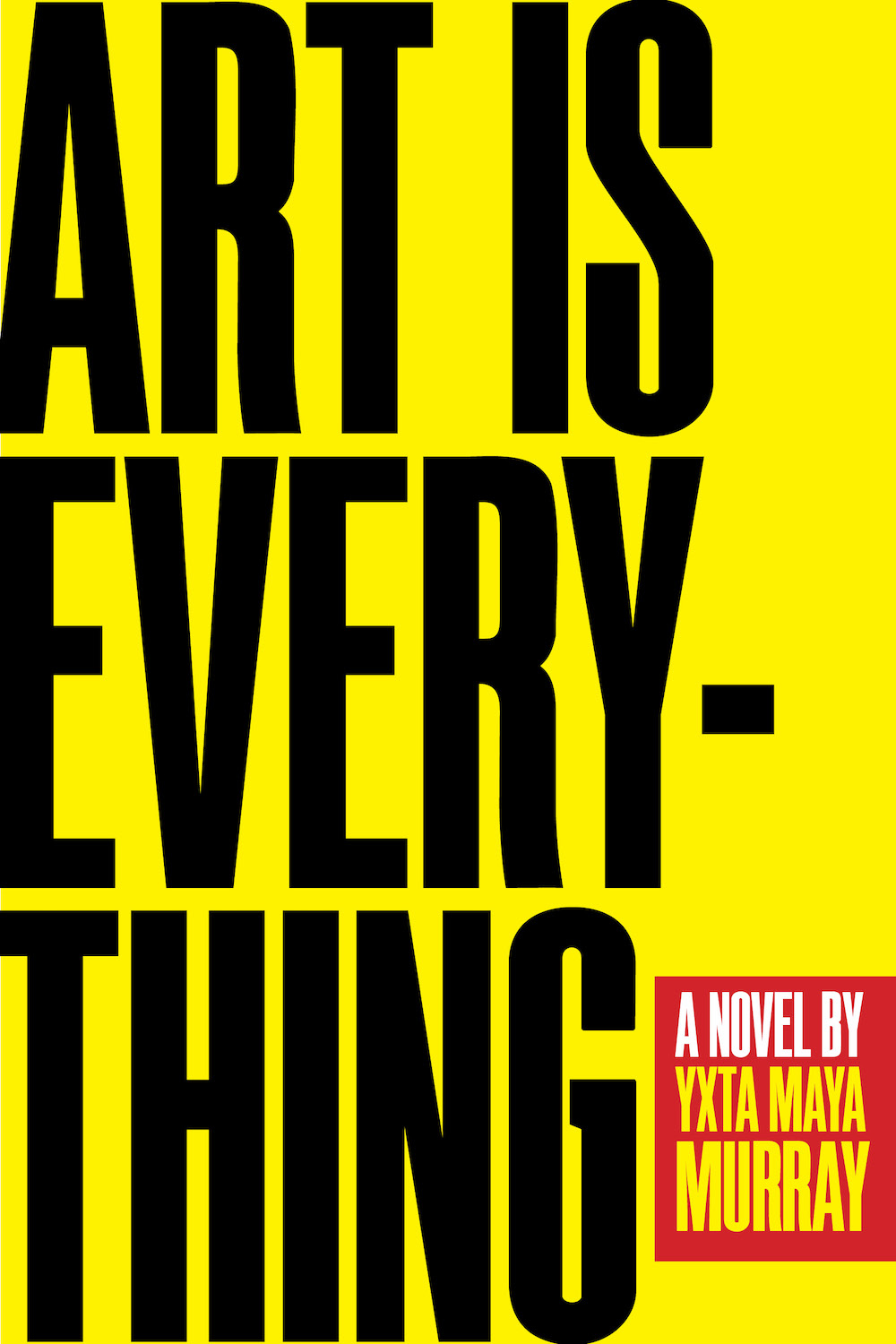

Art Is Everything

By Yxta Maya Murray

229 pages

TriQuarterly

Yxta Maya Murray—art writer, law professor, fiction author—draws upon the disparate threads of her writing practice to construct her new novel, Art Is Everything, a kind of Bildungsroman of the Los Angeles art world.

Written as a series of first-person confessions and guerrilla essays penned by the novel’s sole narrator, queer Chicanx performance artist Amanda Ruiz, the tale is pieced together in a series of snapshots as Ruiz’ art career rises and falls, along with her personal relationships. The novel kicks off with an article of indictment titled, “Hey MOCA, why is Laura Aguilar’s Untitled Landscape (1996) ‘Unavailable’ on Your Website?”

Interspersed with Ruiz’ essay on Aguilar’s invisibility come declarations of love and desire for her girlfriend X–ochitl Hernández, who she describes in ways that intersect with Aguilar—“large-bodied, queer, and of a complex racial background.” Exposing the kind of erasure she also encounters as a queer Chicanx artist and shares with Aguilar, she writes,“… museums either do not collect her, or they conceal her as if they are ashamed.”

The authur, photo by Andrew Brown.

Ruiz audaciously places her essays as disruptive acts, hacking museum websites with unauthorized texts, subverting Wikipedia with position pieces, and leveraging social media. One guerrilla post, on the Whitney Museum website, skewers the Max Mara Whitney bag as an unattainable object and unmasks the commercialism of the art world’s high temples. Ruiz’ many compelling texts—on, for example, Sanja Ivakovi´c’s performance implicating the state surveillance apparatus of Yugoslav strongman president, Marshal Tito (Triangle, 1979); Mickalene Thomas’ Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noires (2010) and Stendhal; or David Wojnarowicz’ death portrait of Peter Hujar—are clearly informed by Murray’s art- and law-writing. Indeed, some have their origins in articles published previously, as noted in her acknowledgments. Yet they are wholly believable as Ruiz’ work, composed here in her voice.

In spite of Ruiz’ convincingness as a writer—with a punk-rock ethos—she seems miserable as an artist. Ain’t Nobody Leaving, the performance film that wins her a coveted Slamdance award, ironically documents the dissolution of her relationship with the long-suffering Xochitl, as well as a performance in the extreme—seven days of self-starvation and semi-hallucination. Yet the film feels juvenile and the dialogue utterly pedestrian: “I’m really hungry and I can’t believe that you are eating that sandwich in front of me,” and “What does love even mean?” Her other projects feel one-dimensional as well.

In an early essay on Agnes Martin and Jean Genet, Ruiz asks how artists survive a break—foreshadowing the impending attenuation of Ruiz’ art production, which withers away post-X–ochitl. In a particularly exquisite chapter titled “Private Language”—on Wittgenstein, Melville and Hawthorne, the semiotics of love, and the limitations of our subjectivity—Ruiz writes on what it feels like to be destroyed by love. The final third of the novel answers these two concerns in a variety of ways, each acknowledging the difficulty of making a life after loss and the death of one’s dreams. It is no surprise that Ruiz turns to art writing when her performance work is exhausted, for that is what she has been all along—a writer—which we readily recognize from the handiwork of Ruiz’ dexterous creator.