What is a colorist painter? In the 19th century, the painter and critic Eugène Fromentin assessed that the work of colorist artists engage hues that are “rare, tender, or powerful, but resolutely [achieved by] a man skillful in feeling distinctions, or in rendering them.” Today, colorists might be defined as artists who use striking pigments to ask new questions about art and society: practitioners include Barbara Friedman, whose stunning, funny and risk-taking paintings talk back to the Color Field pioneers, Stanley Whitney, who challenges the canon with his stoplight-yellow and candy-pink grids that quote Agnes Martin, and Jeffrey Gibson, who currently represents the US in Venice with prismatic, multidisciplinary work that comments on Indigeneity, conquest and queerness.

In Southern California, Anne Austin Pearce offers a rousing contribution to this genre of art with “River Deep–Mountain High,” her new exhibition at Soka University’s 8,900 square-foot Founders Gallery in Aliso Viejo. Pearce, who was born in Kansas and received her MFA at James Madison University, has taught art at Soka since 2019 and permanently moved to California in 2020, just around the time that the pandemic hit. In “River Deep-Mountain High,” the viewer is introduced a summation of Pearce’s vivid practice pre-and post-COVID.

Blue, here, is a consistent color, perhaps because Pearce’s university is close to Aliso Beach, a turquoise stretch of the Pacific that was largely empty of people during the most intense periods of the pandemic. This influence is felt in Icarus/Blue Sea (2024), where Pearce has fashioned a massive, swirling work out of cut paper, inks and kaleidoscopic acrylics, assembling these individual painted pieces of papier collé over entire walls of the Founders Gallery until they form hyperreal and amorphous shapes. These swoop across the eye like a flock of birds—or are we looking instead at a swarm of iridescent insects? A tidal wave? Flying dolphins? When enveloped by Pearce’s flowing, flying blue-green-pink-orange-black atmosphere, I felt my heart beating a little harder. It seemed I had entered a strange Eden that existed in a pristine and hallucinatory state—which is not only a reflection on the longing for a more perfect world that struck so many people c. 2020, but also the clear, smogless air that SoCal momentarily “enjoyed” during that weird, grief-struck spring.

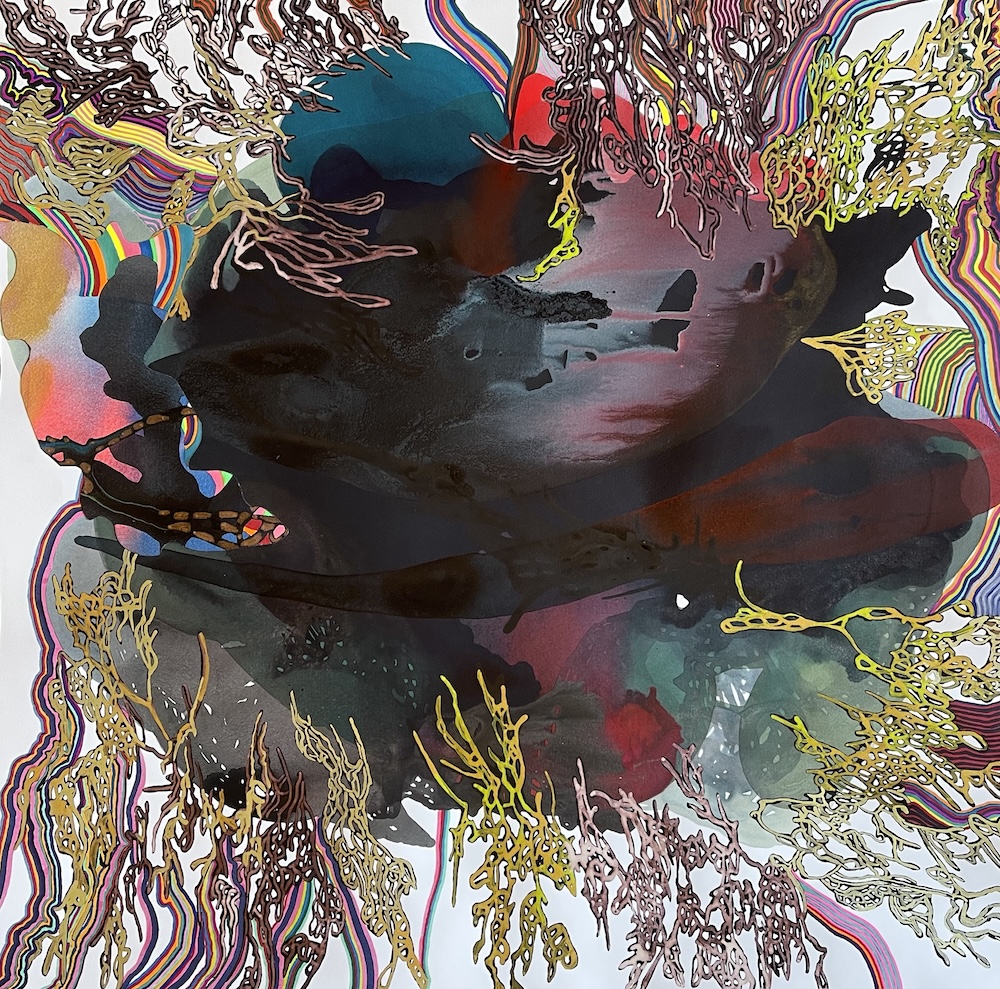

Moonlit High Tide, 2023, Ink, acrylic, collage on paper, 50″ x 38″, 2023

This bracing effect is conveyed in Pearce’s other works, which are contained in frames. Such is the case, for example, in Tidal Exit (2023), where Pearce creates a Day-Glo abstract form that could be a mussel bed, an oil spill or roving school of biofluorescent fish. Moonlight High Tide (2023) is a study of sap greens, moss, that dark-black green of magnolia leaves, indigos. and slices of peach and dandelion, evoking a tidal pool churning with amphibious life. San Clemente Gloaming (2023) offers another study in color and multiplicity: Anchored by bright fuchsia, and laced with bitter orange, black, burgundy, mint and tangerine, the collage does not offer the eye a place to rest, but insists on its own abundance, like cell division, birth, or any other struggle for life.

In April, I tracked down Pearce to ask her about her treatment of color, her place in the colorist practice, and the significance of her latest show. She spoke to me between teaching her classes at Soka, where the semester is beginning to wind down in preparation for the summer break.

Icarus / Blue Sea, Ink, acrylic and pen on paper, 2024

XMM: Your paintings and collages have such an acute sense of tone, shade, and color intensity. They’re reminiscent of the natural world but also take part in a contemporary conversation about the meaning of color in today’s society. Why did you decide to make color such an important part of your work?

AAP: Color for me represents resilience; a life force and ultimate joy in the face of the opacity regarding the natural world. I think a great deal about the differences between mediated color and analog color and the tethers to memory, place, people, time of day, and so on. For example, I will choose pink and green because it flings me back to age 17 and seeing someone in OP green shorts with a pink shirt. Color is what drives the emotion that I hope to invoke in my work.

Which painters have influenced your approach to color? Did you cut your teeth on Fauvism when you were young? Did you wander into a room of Rothkos at the Museum of Modern Art? Did the Helen Frankenthaler bug bite you?

All of them and more. I like Frida Kahlo and Henri Julien Félix Rousseau and the colors they used to create jungles. While trying to remember my first experiences with color in the context of art, the first and most impactful experience I had was when I was five years and encountered Aboriginal bark paintings located in an apartment loft apartment in Lawrence, Kansas.

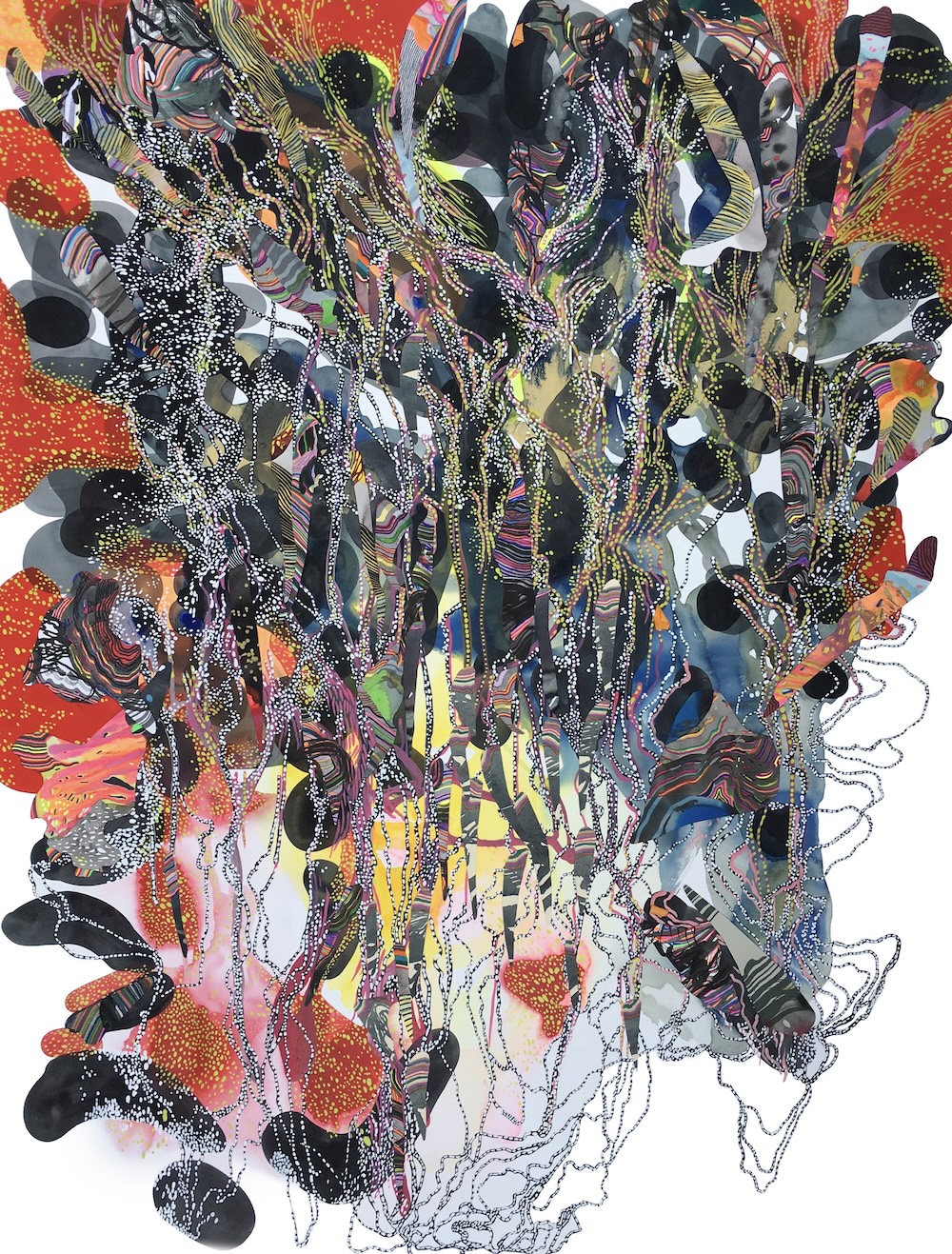

Super Hot Heavy, 2020, ink, acrylic and collage on paper, 38″ x 50″

2020

Your work seems to have an environmental focus—it’s made doubly apparent by some of the titles of your works. Are you celebrating a nature that has passed, or are you fighting for a future that you refuse to give up on?

Both. Nature is almost like a deity to me, and I seek to observe and admire natural processes in my work; the past, present, and future. I absolutely refuse to give up on the natural world; in nature things die, things evolve, and wonderful new things are discovered.

What’s your process like?

I wake early and answer emails from bed where my fine husband delivers coffee. Close the computer and my eyes for a moment and wander around a daydream about the work I left the night before. Unless I am teaching, traveling, or attending a meeting, I paint daily, and I love it.

Spider, 2021, Ink and acrylic on paper, 25″ x25″

Tell us about your journey to “River Deep-Mountain High:” What were you grappling with when making the work that is presented in the show? How were you able to translate the difficulties of the pandemic to such a large space as the Founders Gallery? Also, what spaces informed the work that occupies the show? Did you do research? Did you travel? Did you journal?

The works in the exhibition were started months prior to the pandemic and continued from 2019 – 2022. The world was tumultuous on myriad social levels and by the time the pandemic was in full swing, my life simply rotated between home, the Soka University of America campus and multiple trips the ocean. I treated this time, the newness of the geography and the environment, and regular communion on the campus with animals (deer, skunks, rabbits, owls, red-tailed hawks, coyotes, bobcats, voles, snails and praying mantis) as unique and special. I had to treat it this way because there was no other real option. I tried to make work that was reflective of the actual earth taking a rest and attempted to celebrate other forms of life, such as plants and animals thriving, who perhaps found themselves enjoying newly-found quiet and a bit less pollution.

Where you do you get your ideas for paintings? Do you borrow from your life experience? Or are you inspired by your readings? Do you overhear a conversation or listen to the sound of someone laughing and imagine scenes in your head? Or is the process more mysterious, less connected to language?

My ideas are organic and are reminiscent of plants growing between the cracks of a stone path, they appear as small green shoots and evolve. Collecting and observing, experiences layer on one another and continue shape-shifting and re-settling as new ones are acquired.

Tidal Exit, 2023,

Ink, acrylic, collage on paper, 50′ x 64″

Describe your practice of liberating the art from the frame and allowing it to travel over the walls. In some ways, this reminds me of the strengths of set design, which create a world that viewers or actors inhabit. What kind of different relationship can viewers have with art when they are not just looking at a framed picture but rather at an atmosphere that is encircling them?

We did not simply step into nature but rather that we came from nature. We humans have fully adopted the idea that we are somehow divorced or unconnected from nature, and that we sit atop mother nature as if we are some unrelated entity, but this is untrue. I hope that liberating the artwork from the frame and allowing it to froth around the audience who see and experience it will rekindle our connection to the natural world.

This interview has been edited for space and clarity.

https://www.soka.edu/founders-gallery

Through September 12, 2024